Difference between revisions of "John D'Emilio: "Writing for Freedom," 1970s"

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

Putting on these conferences was a massive amount of work. In 1978, Kuda announced that the fifth was likely to be the last. But she shared with those who were there her utopian fantasy of the future: “My greatest dream is for a weeklong festival of lesbian arts with music at one end, literature at the other. In between, all the visual arts. Wouldn't it be great at McCormick Place—right after Illinois passes the ERA?” | Putting on these conferences was a massive amount of work. In 1978, Kuda announced that the fifth was likely to be the last. But she shared with those who were there her utopian fantasy of the future: “My greatest dream is for a weeklong festival of lesbian arts with music at one end, literature at the other. In between, all the visual arts. Wouldn't it be great at McCormick Place—right after Illinois passes the ERA?” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align: right; direction: ltr; margin-left: 1em;">• Go to [http://www.outhistory.org/wiki/John_D%27Emilio:_%22The_Lavender_Scare_in_Chicago%2C%22_1950s | Next Article]</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category: Bisexual]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Building a Post-War World, 1945-1970]] | ||

| + | [[Category: D'Emilio, John (1948 - )]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Gay]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Kuda, Marie (????- ) ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Lesbian]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Living Contemporary Lives, 1970-Present]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Taylor, Valerie (1913-1997)]] | ||

| + | [[Category:20th century]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:42, 4 February 2009

"culture as a force for liberation "

This essay appeared in the Windy City Times, October 22, 2008, and is published on OutHistory.org with the permission of that paper and the author. Copyright (c) 2008 by John D'Emilio. All rights reserved.

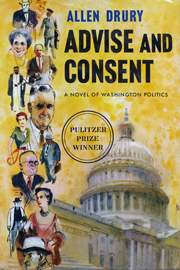

If I think back on the steps that brought me to embrace being gay, they follow a path littered with books. First was Advise and Consent, a wildly popular novel from the late 1950s that I read before starting high school. The main character, a senator who had a gay affair while in the army, commits suicide when he's threatened with exposure. From there I moved on to Another Country by James Baldwin. One gay character kills himself. Another finds happiness, but only by moving to France. My life prospects had now improved to 50-50, but how would I get to France?

In college, I read Oscar Wilde's De Profundis. It's an eloquent, passionate, and strong-willed defense of love between men, but Wilde wrote it while in jail, which is where, apparently, you end up if you're gay. Books were letting me imagine that there were other homosexuals in the world. They were even giving me the words to defend my feelings and attractions. But jolly and hopeful they weren't.

Then, in 1973, Mimi, a friend who identified as bisexual and lived in a group household, gave me a brand-new novel that, Mimi said, she read in a single sitting. It was published by something called Daughters Press, a feminist collective in Vermont; the author was a lesbian activist named Rita Mae Brown; and the intriguing title was Rubyfruit Jungle.

Sure enough, it was an irresistible page-turner. Brown seized upon core American themes and shaped them into a completely lovable lesbian coming-of-age story. Molly Bolt, the narrator, perfectly fit the mold of a rugged individualist; she was determined to clear her own path in life. Just like the heroes of 19th-century Horatio Alger novels, with luck and pluck Molly was going to rise from her dirt-poor origins until success was hers. She did all this with a side-splitting, sassy humor that made me laugh out loud. Sure, as a woman and a dyke she faced trials and tribulations. But you knew—I knew—that nothing would stop her. I had never before read anything like this, and I, too, stayed up all night to finish.

I don't think it was an accident that the author of Rubyfruit Jungle had already cut her teeth in the lesbian, gay and women's liberation movements. Rita Mae Brown created a ruckus in the National Organization for Women when she raised lesbian issues. She helped write “The Woman-Identified Woman,” one of the classic radical lesbian manifestos of the time ( its opening line: “What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion.” ) . As part of the “Lavender Menace” contingent, she disrupted a feminist conference in 1970 in order to make lesbian issues visible. Brown was also in the collective that published The Furies, an influential lesbian-feminist journal of that period.

Rubyfruit Jungle was a new kind of queer writing. It was writing designed to set its readers free. Now that kind of political writing, I know, can lead to some pretty dreadful books. But, in this case, it produced a novel that, 35 years later, still thrills readers of every sexual persuasion. Reading it in 1973 alerted me to something that was going on among lesbian activists that I didn't yet see happening much in my gay male circles. Lesbian feminists seemed to believe in the power of culture to help remake the world.

Chicago's Early Queer Newspapers

One way of grasping this difference is to look at two of Chicago's early queer newspapers: Lavender Woman ( LW ) , which ran from 1971 to 1976; and Gay Crusader, published between 1973 and 1976. At the risk of a generalization that I know won't hold true for every page, the Crusader tended to report on news and events. It was about the activities of a movement—demonstrations, organizations, political happenings. LW was about culture, consciousness, and ideas. It covered at length the new world of women's music. It explored lesbian literary history. It was as likely to have a centerfold of poems as it was to include photos of a rally.

Lesbian Writers Conferences, 1974-1978

This emphasis on culture as a force for liberation shines through in the annual lesbian writers conferences held in Chicago between 1974 and 1978. The conferences were the inspiration of Marie Kuda, whose own history of community activism stretched back before Stonewall. Valerie Taylor, who keynoted the first conference, remembered getting a telephone call near the end of Chicago's winter. She heard Kuda saying “What we need here is a lesbian writers' conference!” So Taylor said “fine” and a few women gathered at her North Side apartment to begin planning. According to Taylor, Kuda was “the energy and the brain power” behind all five conferences.

The conferences took place on the South Side, initially at First Unitarian Church in Hyde Park, and later at the Blue Gargoyle. Women came from as far away as Boston, Florida and Colorado. Even though some notable figures attended—Paula Christian who, besides Taylor, was another icon of the lesbian-pulp era, spoke at one—Kuda meant the conferences as “a meeting of equals.”

Saturdays consisted of a series of workshops that, according to one participant, filled “every nook and cranny of the First Unitarian Church, from the loft to the crypts.” Workshops ran the gamut from the practical to the creative to the slightly ridiculous. Given the strong homophobic bias among mainstream publishers, lesbian writers worked hard to master the technicalities of self-publishing. Independent lesbian presses were springing up around the country in he 1970s, and these Chicago conferences helped lesbians teach each other the mechanics of publication and distribution. Representatives of women's presses and magazines came each year and generously shared their mailing lists. By the third gathering in 1976, one attendee commented that “slowly and methodically lesbians are beginning to chip away at barriers that seemed impenetrable.”

Many of the sessions focused on the creative process. There were workshops on fiction, poetry, journalism, and theater. Women risked the vulnerability of sharing their work with strangers. At one workshop, lesbian feminist beliefs in collectivity led to the writing of a short story together, with each participant contributing a sentence at a time. This drove at least one of the women there to the edge of distraction. But more often, women left workshops filled, as one wrote, with “an intense and exhilarating energy.”

The conferences also paid respect to lesbian literary history. “All of us build on the lives of those who have gone before,” Valerie Taylor told those at the first conference. Keynote speakers described the work of writers from Sappho through Virginia Woolf. Others presented slide shows with images of writers and their books. Tee Corinne gave a presentation on the visual history of lesbian sexuality with a sampling of the 5,000 slides she had amassed in the course of her research. These conferences were about the creative process, for sure. But they also attempted to teach history at a time when there weren't many queer courses in colleges and universities.

And there were moments of fun. I wish I could have been at the Saturday night party in 1978 when many of the attendees came in costume, dressed as their favorite lesbian literary hero.

Putting on these conferences was a massive amount of work. In 1978, Kuda announced that the fifth was likely to be the last. But she shared with those who were there her utopian fantasy of the future: “My greatest dream is for a weeklong festival of lesbian arts with music at one end, literature at the other. In between, all the visual arts. Wouldn't it be great at McCormick Place—right after Illinois passes the ERA?”