Difference between revisions of "Queer Bronzeville's Pre-History"

m (ref +ref) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | == Magnus Hirschfeld in Chicago == | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Since the end of the nineteenth century, the activities of African-American homosexuals, major characters in the neighborhood’s social and cultural life, had been discussed by sexologists, sociologists, academics, and journalists, all of whom described meticulously well-organized homosexual “communities” which were relatively well-accepted by the neighborhood’s inhabitants.<ref>See Bibliography</ref> | Since the end of the nineteenth century, the activities of African-American homosexuals, major characters in the neighborhood’s social and cultural life, had been discussed by sexologists, sociologists, academics, and journalists, all of whom described meticulously well-organized homosexual “communities” which were relatively well-accepted by the neighborhood’s inhabitants.<ref>See Bibliography</ref> | ||

| Line 6: | Line 10: | ||

Courtesy of the Newberry Library. | Courtesy of the Newberry Library. | ||

]] | ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Black Newspapers and Queer Subjects == | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

As Chicago’s Black population grew at the beginning of the twentieth century, Bronzeville counted a number of Black newspapers such as The Chicago Bee, the Chicago Whip or the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_Defender Chicago Defender]. In order to foster a sense of community, these publications relied heavily on community gossips and entertainment reviews. <ref>Ralph Nelson Davis, “The Negro Newspaper in Chicago,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago, 1939)</ref> | As Chicago’s Black population grew at the beginning of the twentieth century, Bronzeville counted a number of Black newspapers such as The Chicago Bee, the Chicago Whip or the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_Defender Chicago Defender]. In order to foster a sense of community, these publications relied heavily on community gossips and entertainment reviews. <ref>Ralph Nelson Davis, “The Negro Newspaper in Chicago,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago, 1939)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

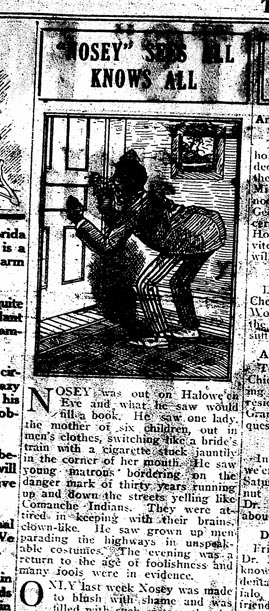

| + | [[Image:NoseySeesAllKnowsAll.jpg|frame|none|“Nosey Sees All Knows All,” Chicago Whip, November 6, 1920, 2 : "Nosey was out on Haloween Eve and what he saw would fill a book. he was one lady, the mother of sex children, out in men's clothes, switching like a bride's train with a cigarette stuck jauntily in the corner of her mouth."]] | ||

| + | |||

The Chicago Whip often commented on homosexuals’ presence in the Stroll, the main street of Bronzeville. The column “Nosey Sees All Knows All,” written under the pen name “Nosey,” often discussed the lives of Bronzeville’s homosexuals. In November 1919, Nosey, who was “out on Halloween Eve,” had seen “the mother of six children,” who “had on a pair of men’s trousers, face covered with powder, with hair cut just like a woman.” <ref>“Nosey Sees All Knows All,” Chicago Whip, November 6, 1920, 2 ; Id., December 4, 1920, 2.</ref> While these descriptions attest to the visibility of queers on Chicago’s South Side, and their relative acceptance; the writer does not appear to show hostility toward the people he described. Homosexuality, in its everyday existence, rarely made the front page of the newspapers. Rarely would the Chicago Whip publish articles regarding unfortunate outings, such as this November 1920 article asking the question “Have We Had a Sex Problem Here?” This article told the story of Sherman Robinson, resident of 3521 Wabash Avenue, the “plaintiff in one of Chicago’s most unusual divorce cases.” According to the reporter, the couple had “been living happily until September 1916, when Ida [Robinson’s wife] had left [him] for a woman she had previously met in Paducah, Kentucky.”<ref> “Have We Had A Sex Problem Here?”, Chicago Whip, November 27, 1920 </ref> | The Chicago Whip often commented on homosexuals’ presence in the Stroll, the main street of Bronzeville. The column “Nosey Sees All Knows All,” written under the pen name “Nosey,” often discussed the lives of Bronzeville’s homosexuals. In November 1919, Nosey, who was “out on Halloween Eve,” had seen “the mother of six children,” who “had on a pair of men’s trousers, face covered with powder, with hair cut just like a woman.” <ref>“Nosey Sees All Knows All,” Chicago Whip, November 6, 1920, 2 ; Id., December 4, 1920, 2.</ref> While these descriptions attest to the visibility of queers on Chicago’s South Side, and their relative acceptance; the writer does not appear to show hostility toward the people he described. Homosexuality, in its everyday existence, rarely made the front page of the newspapers. Rarely would the Chicago Whip publish articles regarding unfortunate outings, such as this November 1920 article asking the question “Have We Had a Sex Problem Here?” This article told the story of Sherman Robinson, resident of 3521 Wabash Avenue, the “plaintiff in one of Chicago’s most unusual divorce cases.” According to the reporter, the couple had “been living happily until September 1916, when Ida [Robinson’s wife] had left [him] for a woman she had previously met in Paducah, Kentucky.”<ref> “Have We Had A Sex Problem Here?”, Chicago Whip, November 27, 1920 </ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:11, 13 March 2009

Magnus Hirschfeld in Chicago

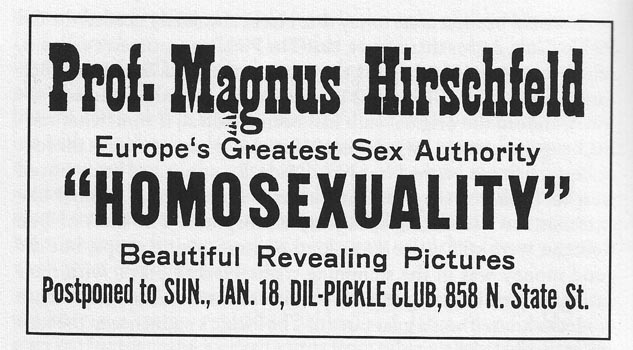

Since the end of the nineteenth century, the activities of African-American homosexuals, major characters in the neighborhood’s social and cultural life, had been discussed by sexologists, sociologists, academics, and journalists, all of whom described meticulously well-organized homosexual “communities” which were relatively well-accepted by the neighborhood’s inhabitants.[1]

German sexologist Magnus Hirschfield was the first to discuss his encounters with African-American homosexuals in Chicago, in his numerous studies on homosexuality in American cities. In his book Homosexuality in Men and Women, the product of his research carried out in 1893, the sexologist discussed “an encounter with a Negro girl” who “turned out to be a male prostitute,” thus establishing the first proof of queer life in Chicago’s Black community. Hirschfield however does not in fact determine the sexual orientation of the young Black man on Clark Street, nor his geographical location (North or South), and gives no concrete proof of his activities (the mere fact that he was on Clark Street or that he was wearing women’s clothing does not necessarily mean he was a prostitute.)[2]

Black Newspapers and Queer Subjects

As Chicago’s Black population grew at the beginning of the twentieth century, Bronzeville counted a number of Black newspapers such as The Chicago Bee, the Chicago Whip or the Chicago Defender. In order to foster a sense of community, these publications relied heavily on community gossips and entertainment reviews. [3]

The Chicago Whip often commented on homosexuals’ presence in the Stroll, the main street of Bronzeville. The column “Nosey Sees All Knows All,” written under the pen name “Nosey,” often discussed the lives of Bronzeville’s homosexuals. In November 1919, Nosey, who was “out on Halloween Eve,” had seen “the mother of six children,” who “had on a pair of men’s trousers, face covered with powder, with hair cut just like a woman.” [4] While these descriptions attest to the visibility of queers on Chicago’s South Side, and their relative acceptance; the writer does not appear to show hostility toward the people he described. Homosexuality, in its everyday existence, rarely made the front page of the newspapers. Rarely would the Chicago Whip publish articles regarding unfortunate outings, such as this November 1920 article asking the question “Have We Had a Sex Problem Here?” This article told the story of Sherman Robinson, resident of 3521 Wabash Avenue, the “plaintiff in one of Chicago’s most unusual divorce cases.” According to the reporter, the couple had “been living happily until September 1916, when Ida [Robinson’s wife] had left [him] for a woman she had previously met in Paducah, Kentucky.”[5]

- ↑ See Bibliography

- ↑ Magnus Hirschfeld, Homosexuality in Men and Women (New York : Prometheus Book, 1914) ; Jonathan Ned Katz, Gay American History : Lesbians and Gay Men in the USA (1972, New York: Meridan, 1992) 48.

- ↑ Ralph Nelson Davis, “The Negro Newspaper in Chicago,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago, 1939)

- ↑ “Nosey Sees All Knows All,” Chicago Whip, November 6, 1920, 2 ; Id., December 4, 1920, 2.

- ↑ “Have We Had A Sex Problem Here?”, Chicago Whip, November 27, 1920