Difference between revisions of "Bronzeville's Queer NIghtlife"

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

[http://outhistory.org/wiki/The_Drag_Balls NEXT: The Drag Balls] | [http://outhistory.org/wiki/The_Drag_Balls NEXT: The Drag Balls] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:AFRICAN AMERICANS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:CHICAGO]] | ||

| + | [[Category:NIGHTLIFE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:CLUBS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:SLUMMING]] | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 13:37, 29 April 2009

Text by Tristan Cabello. Copyright (©) by Tristan Cabello, 2008. All rights reserved.

The Black and Tans

African-American queers took advantage of the freedom of expression they found in the South Side’s cabarets, epicenters of non-normative sexual practices such as interracial relations, prostitution and homosexual relations. These cabarets, known as “Black and Tans,” naturally accommodated same-sex relations. As early as 1926, Jessie Binford, director of the Juvenile Protective Association, had spotted a group of homosexuals on the dance floor at the Plantation Café, a mainly heterosexual cabaret. [1]

Slumming

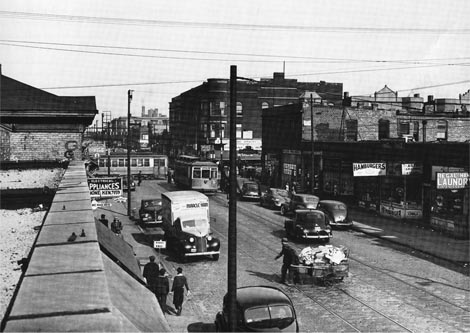

Racial mixing in these cabarets was unexpected, as Chicago authorities, more alarmed by interracial sexual relations than homosexuality, carefully monitored such places. Police authorities, for example, requested that “the owners of Black saloons [did] not allow Whites to enter their saloons and that the owners of White saloons prevent[ed] Black men from entering their establishments.” Bronzeville’s African-Americans were also particularly wary of interactions with Whites. In Black Metropolis, numerous sources from Drake and Cayton admitted acting cautiously when a White person displayed “friendly overtures.” Drake and Cayton acknowledged that even “very friendly approaches from Whites were received with reserve and hesitation, if not unease.” Regarding interracial marriage, many of the participants in Drake and Cayton’s study affirmed that they did not understand why some people would marry a member of another race, as “people understand each other better when they marry members of their own race.” Races appeared to mix more freely in places where homosexuals were present. However, the North Siders who traveled to the South Side did so for very short periods of time. At the Pleasure Inn, on 505 East 31st Street, Whites would come to hear Gloria Swanson until “the sun would hurt their eyes,” and then “they would rush to take a taxi home.” [2]

Racial Integration in Queer Cabarets

This pseudo racial integration, which occurred within the framework of limited interactions between the two races in Bronzeville’s cabarets, did not encourage communication and contact between the two homosexual networks. White homosexuals did not come to the South side out of solidarity for their African-American counterparts.

Club DeLisa

At the end of the 1930’s, the South Side’s most popular gay cabarets were the Club De Lisa, located at 5516 South State Street, and the Cabin Inn, located at [...].Club DeLisa, the high point of Bronzeville’s nightlife, was, according to the Chicago Defender, the “nicest of its kind in town.” Chicago’s Cotton Club, a favorite haunt of the 1930’s most famous jazz musicians, with its “large and poorly-ventilated hall,” could hold up to 500 people, who came to see jazz and blues musicians such as Chippie Hill, Tommy Powell and the De-Ho Boy, and Albert Ammons and his Rhythm Kings. The clubs mainly attracted heterosexuals. At Club De Lisa, frequented by Bronzeville’s middle class, the club owner, Mike DeLisa, rarely presented drag shows.

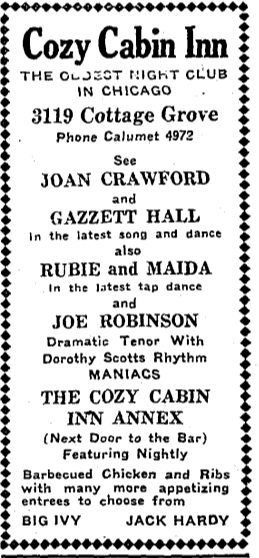

The Cabin Inn

The Cabin Inn, by contrast, was a much less-respected club than the De Lisa, and accepted its status as a drag club, putting on a nightly show. Club owner Nat Big Ivy had opened the Cabin Inn to attract both Whites and Blacks from the working class. Female impersonator Valda Gray, the show’s producer, familiarized Bronzeville’s clubs with such performances, presenting a troupe of Drag Queens; Joanne Crawford, Jean LeRue, Nina McKinney, and Dixie Lee put on a show every night.

- ↑ “Minutes from the Board of Directors Meeting,” Friday, November 12, 1926, Box 182, supplement 1, folder 27, Juvenile Protective Association Papers, Special Collections, The University of Illinois - Chicago, Chicago, IL

- ↑ Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago: a Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1922), 323, 325 ; Drake and Cayton, Black Metropolis, op. cit., 36, 67, 133 ; Danny Barker, as quoted in Howard Reich, “Hotter near the Lake: From King Olivier to Nat King Cole and Beyond, Chicago Has been a Wellspring of Great Jazz,” Chicago Tribune Magazine, September 5, 1931, 6.