Difference between revisions of "Bronzeville's Vice District"

(ref +ref +ref +ref) |

m |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | Text by Tristan Cabello. Copyright (©) by Tristan Cabello, 2008. All rights reserved. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

== The End of the Levee District == | == The End of the Levee District == | ||

| − | Since middle-class Whites did not allow prostitution districts to exist in their own neighborhoods, prostitution prospered in Black urban centers, The Chicago “Levee District” was closed down in 1910s and prostitution centers were rebuilt in new Black neighborhoods. On the South Side, authorities were not bothered by prostitution, which was convenient for the residents of White neighborhoods, who could travel to Black areas as they wished. The “Vice District,” at the intersection of 35th Street and State Street, was part of African-American life in Chicago and had also motivated the migrants to move to Bronzeville. <ref>Neil Larry Shumsky, Tacit Acceptance, Repectable Americans and Segregated prostitution, 1870-1910,” The Journal of Social History 19 (1986): 665-79</ref> | + | Since middle-class Whites did not allow prostitution districts to exist in their own neighborhoods, prostitution prospered in Black urban centers, The Chicago [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levee_District “Levee District”] was closed down in 1910s and prostitution centers were rebuilt in new Black neighborhoods. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | On the South Side, authorities were not bothered by prostitution, which was convenient for the residents of White neighborhoods, who could travel to Black areas as they wished. The “Vice District,” at the intersection of 35th Street and State Street, was part of African-American life in Chicago and had also motivated the migrants to move to Bronzeville. <ref>Neil Larry Shumsky, Tacit Acceptance, Repectable Americans and Segregated prostitution, 1870-1910,” The Journal of Social History 19 (1986): 665-79</ref> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 20: | ||

| − | Conrad Bentzen, a graduate student in Sociology at the University of Chicago, noted that Blacks he interviewed for his research on homosexuals living in the Vice Disctrict “began gambling and visiting whorehouses,” explaining that “the community in which they lived was infested with brothels, whorehouses, gambling, alcohol and drugs,” which, according to the student, contributed to the emergence of non normative sexual preferences among young Black boys. Though Bentzen’s explanations appear to be biased, they were common in this era, when the Chicago Vice Commission’s social reformers declared that they city’s anonymity made it more difficult to “control sexual behavior.” In this study, Bentzen concluded that Bronzeville’s inhabitants were able to essentially “live the life they wished.” <ref>Vice Commission of Chicago, The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions (with recommendations by the Vice Commission of Chicago: a municipal body appointed by the mayor and the City Council of the city of Chicago, and submitted as its report to the mayor and City Council of Chicago) (Chicago : Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, 1911), 218 </ref> | + | Conrad Bentzen, a graduate student in Sociology at the University of Chicago, noted that Blacks he interviewed for his research on homosexuals living in the Vice Disctrict “began gambling and visiting whorehouses,” explaining that “the community in which they lived was infested with brothels, whorehouses, gambling, alcohol and drugs,” which, according to the student, contributed to the emergence of non normative sexual preferences among young Black boys. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Though Bentzen’s explanations appear to be biased, they were common in this era, when the Chicago Vice Commission’s social reformers declared that they city’s anonymity made it more difficult to “control sexual behavior.” In this study, Bentzen concluded that Bronzeville’s inhabitants were able to essentially “live the life they wished.” <ref>Vice Commission of Chicago, The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions (with recommendations by the Vice Commission of Chicago: a municipal body appointed by the mayor and the City Council of the city of Chicago, and submitted as its report to the mayor and City Council of Chicago) (Chicago : Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, 1911), 218 </ref> | ||

| Line 25: | Line 34: | ||

| − | In 1934, the reports of The Juvenile Protection Association described the world of prostitution on the Black belt that prospered from 16th Street to 55th street “in the most flagrant and objectionable type.” According to reporters, street soliciting could be found “on the streets near the fair grounds, on the 30th street, 35th street and 29th street.” Women on the streets had “no scruples about how they [went] about their business,” soliciting “openly before little children, shop keepers standing in front of their places of business, and in any place they can catch the eyes of some man, whether white or black.” The street soliciting in the Black Belt [was not] confined to one area, but, according to the reporters, “along Indiana Ave, South Parkway, Calumet Avenue, Giles Ave., 35th, 31st, 47th and 51st Streets, it was especially noticeable.” In the best residential section, “the street walking prostitutes [were] quite a common thing.” <ref>Houses of prostitutions in Bronzeville: 1800 S Dearborn; 1800 S. Indiana Ave; 4706 S. Parkway; 2100 S. State N.W. 22nd State; Westminster Hotel, 1219 N Clark. “Report of investigations made to date 7-12-34” JPA, Box 5, Folder 89. “General conditions on 35th street between Cottage Grove and State st,” JPA, Fox 5, Folder 90.</ref> | + | In 1934, the reports of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juvenile_Protective_Association The Juvenile Protection Association] described the world of prostitution on the Black belt that prospered from 16th Street to 55th street “in the most flagrant and objectionable type.” [[http://fuzzyco.com/chicago/files/Public_Dance_Halls_of_Chicago.pdf Read Here "The Public Dance Halls in Chicago" by the JPA]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | According to reporters, street soliciting could be found “on the streets near the fair grounds, on the 30th street, 35th street and 29th street.” Women on the streets had “no scruples about how they [went] about their business,” soliciting “openly before little children, shop keepers standing in front of their places of business, and in any place they can catch the eyes of some man, whether white or black.” The street soliciting in the Black Belt [was not] confined to one area, but, according to the reporters, “along Indiana Ave, South Parkway, Calumet Avenue, Giles Ave., 35th, 31st, 47th and 51st Streets, it was especially noticeable.” In the best residential section, “the street walking prostitutes [were] quite a common thing.” <ref>Houses of prostitutions in Bronzeville: 1800 S Dearborn; 1800 S. Indiana Ave; 4706 S. Parkway; 2100 S. State N.W. 22nd State; Westminster Hotel, 1219 N Clark. “Report of investigations made to date 7-12-34” JPA, Box 5, Folder 89. “General conditions on 35th street between Cottage Grove and State st,” JPA, Fox 5, Folder 90.</ref> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 45: | ||

| − | Prostitution was also popular in private villas. Treville Holmes’ villa on 50th Street was, according to writer Samuel Steward, one of the principle centers for homosexual prostitution. This employee of the American Postal Service entertained Bob Hope, Montgomery Clift, Thornton Wilder, James Purdy and intellectuals such as Wendell Wilcox at the end of the 1930’s. Madame Bock offered similar opportunities for sexual adventures. Every weekend, at the beginning of the 1930’s, this Black spiritualist opened an enormous three-story home on the corner of 55th Street and Drexel Boulevard, which was frequented by both Black and White men. For a small admission fee, according to a White homosexual, one could “stay all night and drink all you wanted,” and have sexual relations with the employees and other patrons in one of the house’s many rooms.<ref>Samuel M Steward, interviewed by Gregory A. Sprague, Berkeley, California, May 20, 1982, Sprague Papers; Harvey K. and George P., interviews by Gregory Sprague, ONE institute, Los Angeles, June 3, 1983, Sprague Papers; and “under hypnosis,” section of “My first meeting of the homo” september 1927,” unpublished ms., September 24, 1932, 4, folder 4, box 98, Burgess Papers; James T. Farrell, “Just Boys, 1931-1934,” in the Short Stories of James T. Farrell (Garden City, NY.: Halycon House, 1941)</ref> | + | Prostitution was also popular in private villas. Treville Holmes’ villa on 50th Street was, according to writer Samuel Steward, one of the principle centers for homosexual prostitution. This employee of the American Postal Service entertained [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Hope Bob Hope], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montgomery_Clift Montgomery Clift], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thornton_Wilder Thornton Wilder], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Purdy James Purdy] and intellectuals such as [http://diglib.princeton.edu/ead/getEad?eadid=C0666&kw= Wendell Wilcox] at the end of the 1930’s. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Madame Bock offered similar opportunities for sexual adventures. Every weekend, at the beginning of the 1930’s, this Black spiritualist opened an enormous three-story home on the corner of 55th Street and Drexel Boulevard, which was frequented by both Black and White men. For a small admission fee, according to a White homosexual, one could “stay all night and drink all you wanted,” and have sexual relations with the employees and other patrons in one of the house’s many rooms.<ref>Samuel M Steward, interviewed by Gregory A. Sprague, Berkeley, California, May 20, 1982, Sprague Papers; Harvey K. and George P., interviews by Gregory Sprague, ONE institute, Los Angeles, June 3, 1983, Sprague Papers; and “under hypnosis,” section of “My first meeting of the homo” september 1927,” unpublished ms., September 24, 1932, 4, folder 4, box 98, Burgess Papers; James T. Farrell, “Just Boys, 1931-1934,” in the Short Stories of James T. Farrell (Garden City, NY.: Halycon House, 1941)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [http://www.outhistory.org/wiki/Singing_the_Blues:_Masculine_Female_Performers NEXT: Singing the Blues: Masculine Female Performers] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Protected}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Categories== | ||

| + | [[Category:AFRICAN AMERICANS]] | ||

| + | [[Category:CHICAGO]] | ||

| + | [[Category:PROSTITUTION]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:18, 8 May 2009

Text by Tristan Cabello. Copyright (©) by Tristan Cabello, 2008. All rights reserved.

The End of the Levee District

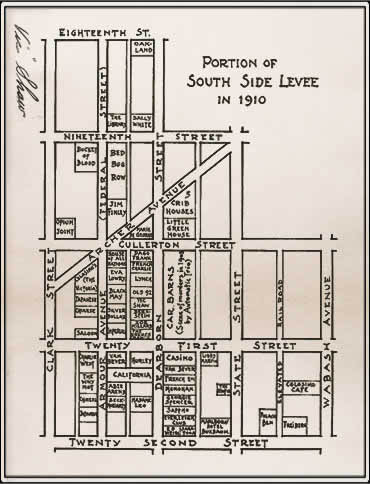

Since middle-class Whites did not allow prostitution districts to exist in their own neighborhoods, prostitution prospered in Black urban centers, The Chicago “Levee District” was closed down in 1910s and prostitution centers were rebuilt in new Black neighborhoods.

On the South Side, authorities were not bothered by prostitution, which was convenient for the residents of White neighborhoods, who could travel to Black areas as they wished. The “Vice District,” at the intersection of 35th Street and State Street, was part of African-American life in Chicago and had also motivated the migrants to move to Bronzeville. [1]

Living in the Vice District

Conrad Bentzen, a graduate student in Sociology at the University of Chicago, noted that Blacks he interviewed for his research on homosexuals living in the Vice Disctrict “began gambling and visiting whorehouses,” explaining that “the community in which they lived was infested with brothels, whorehouses, gambling, alcohol and drugs,” which, according to the student, contributed to the emergence of non normative sexual preferences among young Black boys.

Though Bentzen’s explanations appear to be biased, they were common in this era, when the Chicago Vice Commission’s social reformers declared that they city’s anonymity made it more difficult to “control sexual behavior.” In this study, Bentzen concluded that Bronzeville’s inhabitants were able to essentially “live the life they wished.” [2]

The Juvenile Protective Association

In 1934, the reports of The Juvenile Protection Association described the world of prostitution on the Black belt that prospered from 16th Street to 55th street “in the most flagrant and objectionable type.” [Read Here "The Public Dance Halls in Chicago" by the JPA]

According to reporters, street soliciting could be found “on the streets near the fair grounds, on the 30th street, 35th street and 29th street.” Women on the streets had “no scruples about how they [went] about their business,” soliciting “openly before little children, shop keepers standing in front of their places of business, and in any place they can catch the eyes of some man, whether white or black.” The street soliciting in the Black Belt [was not] confined to one area, but, according to the reporters, “along Indiana Ave, South Parkway, Calumet Avenue, Giles Ave., 35th, 31st, 47th and 51st Streets, it was especially noticeable.” In the best residential section, “the street walking prostitutes [were] quite a common thing.” [3]

Prostitution in Private Villas

Prostitution was also popular in private villas. Treville Holmes’ villa on 50th Street was, according to writer Samuel Steward, one of the principle centers for homosexual prostitution. This employee of the American Postal Service entertained Bob Hope, Montgomery Clift, Thornton Wilder, James Purdy and intellectuals such as Wendell Wilcox at the end of the 1930’s.

Madame Bock offered similar opportunities for sexual adventures. Every weekend, at the beginning of the 1930’s, this Black spiritualist opened an enormous three-story home on the corner of 55th Street and Drexel Boulevard, which was frequented by both Black and White men. For a small admission fee, according to a White homosexual, one could “stay all night and drink all you wanted,” and have sexual relations with the employees and other patrons in one of the house’s many rooms.[4]

NEXT: Singing the Blues: Masculine Female Performers

References

- ↑ Neil Larry Shumsky, Tacit Acceptance, Repectable Americans and Segregated prostitution, 1870-1910,” The Journal of Social History 19 (1986): 665-79

- ↑ Vice Commission of Chicago, The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions (with recommendations by the Vice Commission of Chicago: a municipal body appointed by the mayor and the City Council of the city of Chicago, and submitted as its report to the mayor and City Council of Chicago) (Chicago : Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, 1911), 218

- ↑ Houses of prostitutions in Bronzeville: 1800 S Dearborn; 1800 S. Indiana Ave; 4706 S. Parkway; 2100 S. State N.W. 22nd State; Westminster Hotel, 1219 N Clark. “Report of investigations made to date 7-12-34” JPA, Box 5, Folder 89. “General conditions on 35th street between Cottage Grove and State st,” JPA, Fox 5, Folder 90.

- ↑ Samuel M Steward, interviewed by Gregory A. Sprague, Berkeley, California, May 20, 1982, Sprague Papers; Harvey K. and George P., interviews by Gregory Sprague, ONE institute, Los Angeles, June 3, 1983, Sprague Papers; and “under hypnosis,” section of “My first meeting of the homo” september 1927,” unpublished ms., September 24, 1932, 4, folder 4, box 98, Burgess Papers; James T. Farrell, “Just Boys, 1931-1934,” in the Short Stories of James T. Farrell (Garden City, NY.: Halycon House, 1941)