Difference between revisions of "The Pink and the Blue: 1642-2004"

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

Yale has been responsible for a long list of historic contributions to lesbian and gay scholarship in the United States, which includes everything from founding the first lesbian and gay studies national conferences to establishing the Larry Kramer Initiative itself. With this, the first exhibition to examine the specifically lesbian and gay (and bisexual and transgendered) history of a major institution of higher education in the United States, Yale continues yet another of its celebrated traditions. | Yale has been responsible for a long list of historic contributions to lesbian and gay scholarship in the United States, which includes everything from founding the first lesbian and gay studies national conferences to establishing the Larry Kramer Initiative itself. With this, the first exhibition to examine the specifically lesbian and gay (and bisexual and transgendered) history of a major institution of higher education in the United States, Yale continues yet another of its celebrated traditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =December 1, 1642: CONNECTICUT SODOMY LAW= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Death Penalty for Men== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Colony of Connecticut passed its first sodomy law, providing death for man lying with man. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “If any man lyeth with mankind | ||

| + | |||

| + | as hee lyeth with woman, | ||

| + | |||

| + | both of them have committed abomination, | ||

| + | |||

| + | they both shall surely be put to death.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:01-sodomy-laws-small.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''The Code of 1650, being a compilation of the earliest laws and orders of the General Court of Connecticut. Also the Constitution, or civil compact, entered into and adopted by the towns of Windsor, Hartford and Wethersfield, 1638-9. To which is added, some extracts from the laws and judicial proceedings of New-Haven colony, commonly called blue laws.'' Hartford: S. Andrus and Son, 1845. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =1646: WILLIAM PLAINE= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Executed in New Haven== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Plaine was executed in New Haven for “sodomy with two persons in England,” and for corrupting “a great part of the youth of Guilford by masturbations . . . above a hundred times.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =March 1, 1656: NEW HAVEN COLONY SODOMY LAW= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Death for Men and Women== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The New Haven Colony passed its first sodomy law, a statute unique in colonial legislation for mandating death to both women and men for engaging in sex acts “against nature.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | “If any man lyeth with mankind . . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | both of them have committed abomination, | ||

| + | |||

| + | they both shall surely be put to death. | ||

| + | |||

| + | And if any woman change the natural use, | ||

| + | |||

| + | into that which is against nature . . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | she shall be liable to the same sentence. . . .” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:03-sodomy-laws-small.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''New-Haven’s Settling in New-England: and some lawes for government.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. For permission to reproduce contact Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 4 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =1837: ALBERT DODD= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==A Nineteenth-Century Student’s Diary== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Dodd, a student at Washington College (now Trinity, in Hartford), described in his diary his intense love for men and women, and his intense, affectionate bed-sharing with a male classmate, Anthony Halsey. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Of Halsey, Dodd wrote: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “Tony, how I long to see you, to embrace you, to press you to my bosom, my own dear Tony.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | By September 3, 1837, Dodd transferred to Yale College and transferred his feelings to a Yale freshman, Jabez Sidney Smith, of whom Dodd wrote: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “How much I think all the time continually always of Jabez. I believe I love him.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | At Yale, Dodd studied classic texts of ancient Greece and Rome, and these provided the terms in which he understood his feelings for men and women. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Sketches of Yale College'', a book published in 1840, assured its readers: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “The situation of Yale College, in the midst of an ancient puritan colony . . . [is] favorable to the formation of correct principles.” New Haven’s influence, the book asserted, “is against the fashionable vices of the ancient world.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:04-dodd-diary-small.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Albert Dodd’s diary. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 5 | ||

| + | |||

| + | =1859-1868: ADDIE BROWN AND REBECCA PRIMUS= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==“No kisses is like youres”== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | About a hundred and fifty letters from Addie Brown, a domestic servant, to Rebecca Primus, a teacher, provide extremely rare documentation of a loving, sensual intimacy between two African-American women in the nineteenth century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Brown’s letters were written from Hartford, Farmington, and Waterbury, Connecticut, and from New York City. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Almost every one of Brown’s letters to Primus provides new evidence about their love for each other, and about their complex intimacy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | On October 20, 1867, Brown, a domestic at Miss Porter’s School, in Farmington, wrote Primus about a female coworker, | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ::“sometime just one of them wants to sleep with me. Perhaps I will give my consent some of these nights. I am not very fond of White I can assure you.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Brown’s flirtation with her female coworker evidently caused Primus to express some concern. On November 17, Brown responded, | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ::“If you think that is my bosom that captivated the girl that made her want to sleep with me she got sorely disappointed enjoying [it] for I had my back towards her all night and my night dress was button up so she could not get to my bosom. I shall try to keep you favorite one always for you. Should in my excitement forget you will pardon me I know.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Numbers of letters from Brown to Primus indicate that when visiting they shared a bed along with hugs and kisses. In one letter, Brown told Primus: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ::“No kisses is like youres.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In April 1868, in her late twenties, Addie Brown married Joseph Tines, seemingly for economic security; Brown’s letters suggest that Rebecca Primus remained the love of her life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Sometime between 1872 and 1874, when she was in her thirties, Rebecca Primus married Charles Thomas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | On the back of an envelope of a letter to Brown, Rebecca Primus wrote, “Addie died at home, January 11, 1870.” Brown was twenty-eight. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:05-primus.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Only known photo of Rebecca Primus; with members of the Talcott Street Congregational Church, Hartford, 1922. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Photograph courtesy of the Prudence Crandall Museum. For permission to reproduce contact the Prudence Crandall Museum. | ||

Revision as of 17:38, 6 October 2009

Lesbian and Gay Life at Yale and in Connecticut, 1642-2004

article in construction

THE PINK AND THE BLUE

Lesbian and Gay Life at Yale and in Connecticut, 1642-2004

An exhibit curated by Jonathan Ned Katz

With the research assistance of Brad Walters

Designed by Andrew Sloat

Sponsored by the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies at Yale University

Executive Coordinator, Jonathan David Katz

Sterling Memorial Library Memorabilia Room

February 7 – May 14, 2004

Introduction by Jonathan Ned Katz, Curator

This exhibit begins to piece together fragments of a history not yet written.

It moves chronologically from Connecticut’s early colonial laws mandating death for “sodomy” to the first stirrings, at Yale, of the modern homosexual-rights movement, to the recent development of the Kramer Lesbian and Gay Studies Initiative. It includes stories of individuals and accounts of political organizing.

This is history with a human face, a tale of individual and collective action to make the changing social world.

Spanning 362 years, and focusing on about sixty people and events, this exhibit is, of course, incomplete. It does provide a first, tantalizing glimpse of tales that involve law, religion, morality, medicine, public health, politics, education, immigration, African-American and white culture, and women’s and men’s social lives. It presents materials relevant to transgender, bisexual, gay, and lesbian concerns.

This history illuminates the changing social organization of genders, sexualities, and intimacies, their place in the larger social world, and the evolving reactions of that larger world.

This is a history still in the making. The evidence here can be amplified and analyzed in dozens of undergraduate term papers and graduate-school theses.

Viewers of this exhibit are encouraged to add their comments here.

Introduction by Jonathan David Katz,

Executive Coordinator, Larry Kramer Initiative

As this exhibition makes clear, it is impossible to conceive of a Yale University absent its lesbian and gay past. Building on that past—and occasionally in spite of itself—Yale has emerged at the center of the scholarly and institutional development of lesbian and gay studies today. With the advent of the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies, which brings you this exhibition, Yale’s storied gay and lesbian history now has a dedicated home.

Yale has been responsible for a long list of historic contributions to lesbian and gay scholarship in the United States, which includes everything from founding the first lesbian and gay studies national conferences to establishing the Larry Kramer Initiative itself. With this, the first exhibition to examine the specifically lesbian and gay (and bisexual and transgendered) history of a major institution of higher education in the United States, Yale continues yet another of its celebrated traditions.

1

December 1, 1642: CONNECTICUT SODOMY LAW

Death Penalty for Men

The Colony of Connecticut passed its first sodomy law, providing death for man lying with man.

“If any man lyeth with mankind

as hee lyeth with woman,

both of them have committed abomination,

they both shall surely be put to death.”

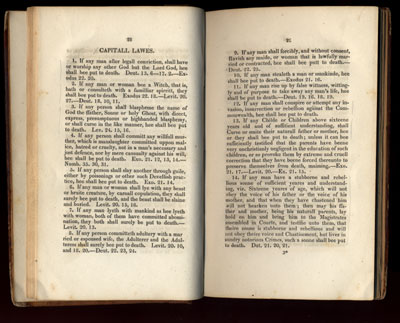

The Code of 1650, being a compilation of the earliest laws and orders of the General Court of Connecticut. Also the Constitution, or civil compact, entered into and adopted by the towns of Windsor, Hartford and Wethersfield, 1638-9. To which is added, some extracts from the laws and judicial proceedings of New-Haven colony, commonly called blue laws. Hartford: S. Andrus and Son, 1845.

2

1646: WILLIAM PLAINE

Executed in New Haven

Plaine was executed in New Haven for “sodomy with two persons in England,” and for corrupting “a great part of the youth of Guilford by masturbations . . . above a hundred times.”

3

March 1, 1656: NEW HAVEN COLONY SODOMY LAW

Death for Men and Women

The New Haven Colony passed its first sodomy law, a statute unique in colonial legislation for mandating death to both women and men for engaging in sex acts “against nature.”

“If any man lyeth with mankind . . .

both of them have committed abomination,

they both shall surely be put to death.

And if any woman change the natural use,

into that which is against nature . . .

she shall be liable to the same sentence. . . .”

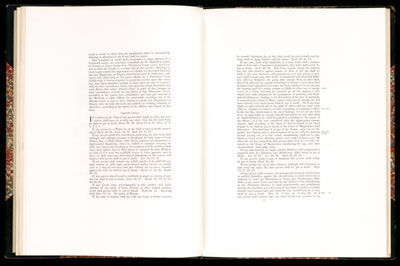

New-Haven’s Settling in New-England: and some lawes for government.

Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. For permission to reproduce contact Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

4

1837: ALBERT DODD

A Nineteenth-Century Student’s Diary

2

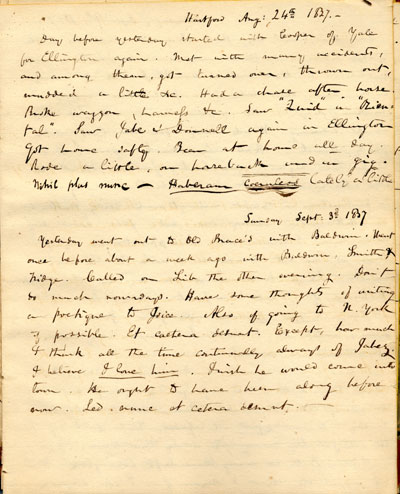

Dodd, a student at Washington College (now Trinity, in Hartford), described in his diary his intense love for men and women, and his intense, affectionate bed-sharing with a male classmate, Anthony Halsey.

Of Halsey, Dodd wrote:

“Tony, how I long to see you, to embrace you, to press you to my bosom, my own dear Tony.”

By September 3, 1837, Dodd transferred to Yale College and transferred his feelings to a Yale freshman, Jabez Sidney Smith, of whom Dodd wrote:

“How much I think all the time continually always of Jabez. I believe I love him.”

At Yale, Dodd studied classic texts of ancient Greece and Rome, and these provided the terms in which he understood his feelings for men and women.

Sketches of Yale College, a book published in 1840, assured its readers:

“The situation of Yale College, in the midst of an ancient puritan colony . . . [is] favorable to the formation of correct principles.” New Haven’s influence, the book asserted, “is against the fashionable vices of the ancient world.”

Albert Dodd’s diary.

Courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

5

1859-1868: ADDIE BROWN AND REBECCA PRIMUS

“No kisses is like youres”

About a hundred and fifty letters from Addie Brown, a domestic servant, to Rebecca Primus, a teacher, provide extremely rare documentation of a loving, sensual intimacy between two African-American women in the nineteenth century.

Brown’s letters were written from Hartford, Farmington, and Waterbury, Connecticut, and from New York City.

Almost every one of Brown’s letters to Primus provides new evidence about their love for each other, and about their complex intimacy.

On October 20, 1867, Brown, a domestic at Miss Porter’s School, in Farmington, wrote Primus about a female coworker,

- “sometime just one of them wants to sleep with me. Perhaps I will give my consent some of these nights. I am not very fond of White I can assure you.”

Brown’s flirtation with her female coworker evidently caused Primus to express some concern. On November 17, Brown responded,

- “If you think that is my bosom that captivated the girl that made her want to sleep with me she got sorely disappointed enjoying [it] for I had my back towards her all night and my night dress was button up so she could not get to my bosom. I shall try to keep you favorite one always for you. Should in my excitement forget you will pardon me I know.”

Numbers of letters from Brown to Primus indicate that when visiting they shared a bed along with hugs and kisses. In one letter, Brown told Primus:

- “No kisses is like youres.”

In April 1868, in her late twenties, Addie Brown married Joseph Tines, seemingly for economic security; Brown’s letters suggest that Rebecca Primus remained the love of her life.

Sometime between 1872 and 1874, when she was in her thirties, Rebecca Primus married Charles Thomas.

On the back of an envelope of a letter to Brown, Rebecca Primus wrote, “Addie died at home, January 11, 1870.” Brown was twenty-eight.

Only known photo of Rebecca Primus; with members of the Talcott Street Congregational Church, Hartford, 1922.

Photograph courtesy of the Prudence Crandall Museum. For permission to reproduce contact the Prudence Crandall Museum.