Difference between revisions of "The Pink and the Blue: 1642-2004"

| Line 356: | Line 356: | ||

| − | [[Image:08-courant.jpg]] | + | [[Image:08-courant.jpg|450px]] |

''Yale Courant'', December 13, 1873.<ref>From the Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Yale University Library.</ref> | ''Yale Courant'', December 13, 1873.<ref>From the Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Yale University Library.</ref> | ||

| − | Laura Johnson Wylie was one of the first three women to receive a Ph.D. in English from Yale, in 1894. The following photograph shows Wylie and Gertrude Buck, Vassar English professors and partners who lived together in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. <ref>Photograph courtesy of Vassar College Archives and Special Collections. For permission to reproduce contact Vassar College Archives.</ref> | + | Laura Johnson Wylie was one of the first three women to receive a Ph.D. in English from Yale, in 1894. The following photograph shows Wylie and Gertrude Buck, Vassar English professors and partners who lived together in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.<ref>Photograph courtesy of Vassar College Archives and Special Collections. For permission to reproduce contact Vassar College Archives.</ref> |

Revision as of 07:38, 7 October 2009

Lesbian and Gay Life at Yale and in Connecticut, 1642-2004

ARTICLE IN CONSTRUCTION

THE PINK AND THE BLUE

Lesbian and Gay Life at Yale and in Connecticut, 1642-2004

An exhibit curated by Jonathan Ned Katz

With the research assistance of Brad Walters

Designed by Andrew Sloat

Sponsored by the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies at Yale University

Executive Coordinator, Jonathan David Katz

Sterling Memorial Library Memorabilia Room

February 7 – May 14, 2004

Introduction by Jonathan Ned Katz, Curator

This exhibit begins to piece together fragments of a history not yet written.

It moves chronologically from Connecticut’s early colonial laws mandating death for “sodomy” to the first stirrings, at Yale, of the modern homosexual-rights movement, to the recent development of the Kramer Lesbian and Gay Studies Initiative. It includes stories of individuals and accounts of political organizing.

This is history with a human face, a tale of individual and collective action to make the changing social world.

Spanning 362 years, and focusing on about sixty people and events, this exhibit is, of course, incomplete. It does provide a first, tantalizing glimpse of tales that involve law, religion, morality, medicine, public health, politics, education, immigration, African-American and white culture, and women’s and men’s social lives. It presents materials relevant to transgender, bisexual, gay, and lesbian concerns.

This history illuminates the changing social organization of genders, sexualities, and intimacies, their place in the larger social world, and the evolving reactions of that larger world.

This is a history still in the making. The evidence here can be amplified and analyzed in dozens of undergraduate term papers and graduate-school theses.

Viewers of this exhibit are encouraged to add their comments here.

Introduction by Jonathan David Katz,

Executive Coordinator, Larry Kramer Initiative

As this exhibition makes clear, it is impossible to conceive of a Yale University absent its lesbian and gay past. Building on that past—and occasionally in spite of itself—Yale has emerged at the center of the scholarly and institutional development of lesbian and gay studies today. With the advent of the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies, which brings you this exhibition, Yale’s storied gay and lesbian history now has a dedicated home.

Yale has been responsible for a long list of historic contributions to lesbian and gay scholarship in the United States, which includes everything from founding the first lesbian and gay studies national conferences to establishing the Larry Kramer Initiative itself. With this, the first exhibition to examine the specifically lesbian and gay (and bisexual and transgendered) history of a major institution of higher education in the United States, Yale continues yet another of its celebrated traditions.

1

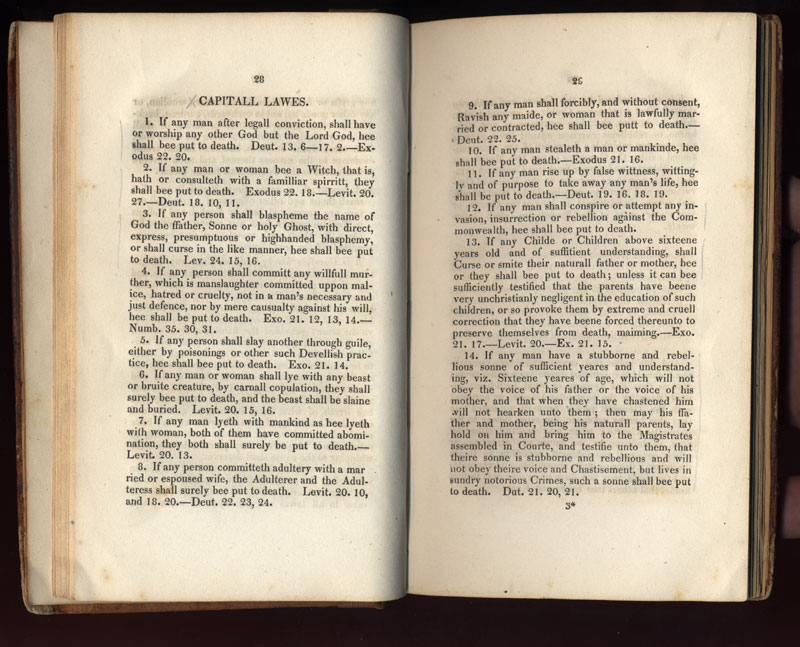

December 1, 1642: CONNECTICUT SODOMY LAW

Death Penalty for Men

The Colony of Connecticut passed its first sodomy law, providing death for man lying with man.

“If any man lyeth with mankind

as hee lyeth with woman,

both of them have committed abomination,

they both shall surely be put to death.”

"The Code of 1650 . . . ."[1]

2

1646: WILLIAM PLAINE

Executed in New Haven

Plaine was executed in New Haven for “sodomy with two persons in England,” and for corrupting “a great part of the youth of Guilford by masturbations . . . above a hundred times.”[2]

3

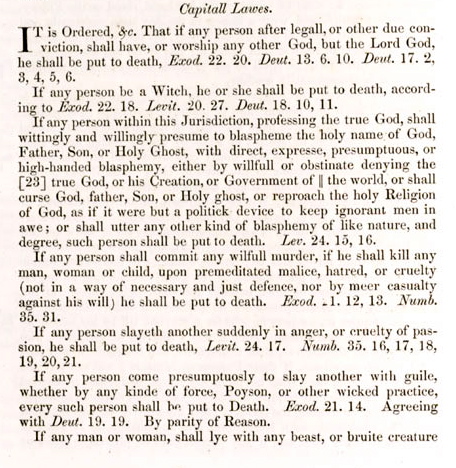

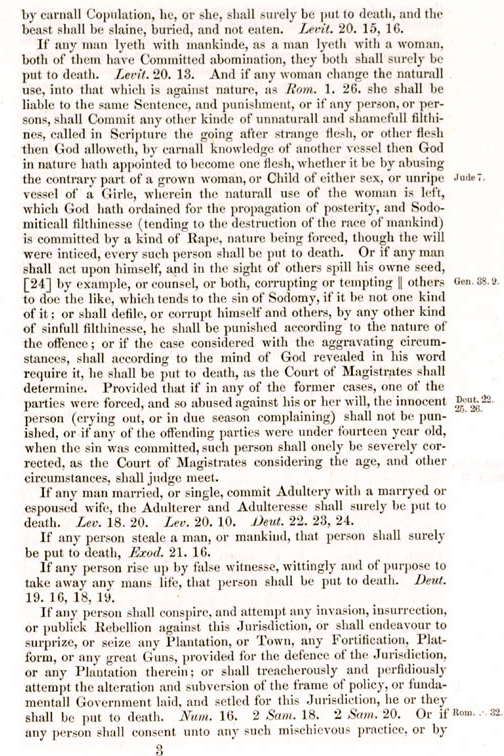

March 1, 1656: NEW HAVEN COLONY SODOMY LAW

Death for Men and Women

The New Haven Colony passed its first sodomy law, a statute unique in colonial legislation for mandating death to both women and men for engaging in sex acts “against nature.”

“If any man lyeth with mankind . . .

both of them have committed abomination,

they both shall surely be put to death.

And if any woman change the natural use,

into that which is against nature . . .

she shall be liable to the same sentence. . . .”

New-Haven’s Settling in New-England: and some lawes for government.[3]

4

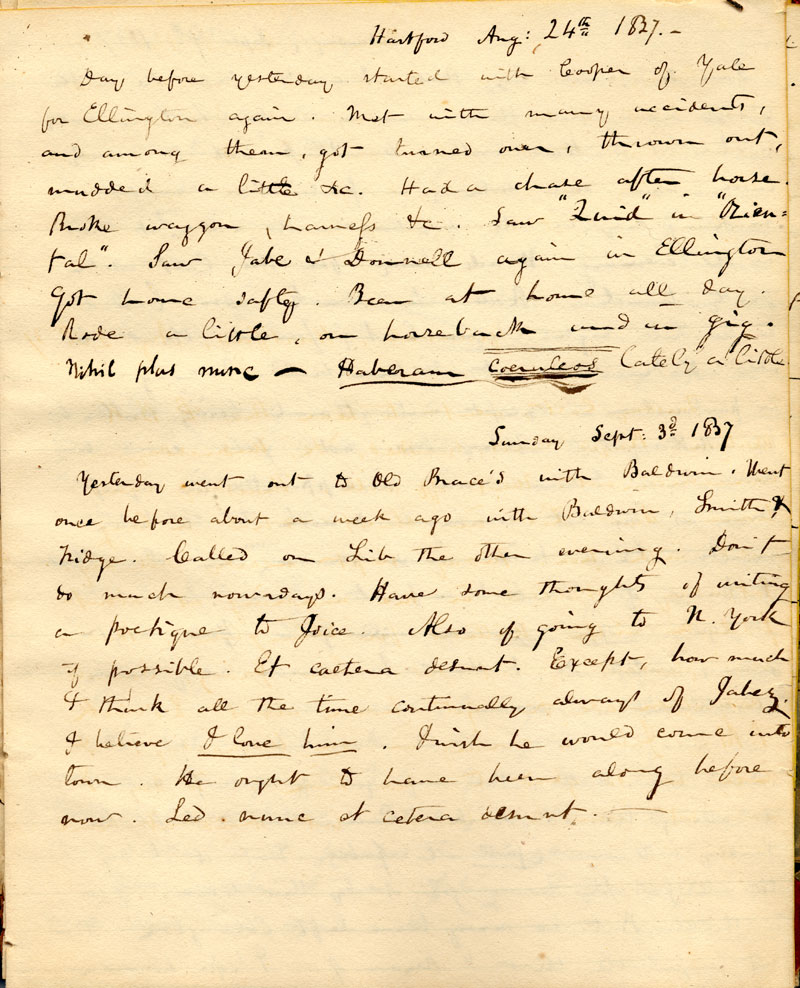

1837: ALBERT DODD

A Nineteenth-Century Student’s Diary

Dodd, a student at Washington College (now Trinity, in Hartford), described in his diary his intense love for men and women, and his intense, affectionate bed-sharing with a male classmate, Anthony Halsey.

Of Halsey, Dodd wrote:

“Tony, how I long to see you, to embrace you, to press you to my bosom, my own dear Tony.”

By September 3, 1837, Dodd transferred to Yale College and transferred his feelings to a Yale freshman, Jabez Sidney Smith, of whom Dodd wrote:

“How much I think all the time continually always of Jabez. I believe I love him.”

At Yale, Dodd studied classic texts of ancient Greece and Rome, and these provided the terms in which he understood his feelings for men and women.

Sketches of Yale College, a book published in 1840, assured its readers:

“The situation of Yale College, in the midst of an ancient puritan colony . . . [is] favorable to the formation of correct principles.” New Haven’s influence, the book asserted, “is against the fashionable vices of the ancient world.”

Albert Dodd’s diary.[4]

5

1859-1868: ADDIE BROWN AND REBECCA PRIMUS

“No kisses is like youres”

About a hundred and fifty letters from Addie Brown, a domestic servant, to Rebecca Primus, a teacher, provide extremely rare documentation of a loving, sensual intimacy between two African-American women in the nineteenth century.

Brown’s letters were written from Hartford, Farmington, and Waterbury, Connecticut, and from New York City.

Almost every one of Brown’s letters to Primus provides new evidence about their love for each other, and about their complex intimacy.

On October 20, 1867, Brown, a domestic at Miss Porter’s School, in Farmington, wrote Primus about a female coworker,

- “sometime just one of them wants to sleep with me. Perhaps I will give my consent some of these nights. I am not very fond of White I can assure you.”

Brown’s flirtation with her female coworker evidently caused Primus to express some concern. On November 17, Brown responded,

- “If you think that is my bosom that captivated the girl that made her want to sleep with me she got sorely disappointed enjoying [it] for I had my back towards her all night and my night dress was button up so she could not get to my bosom. I shall try to keep you favorite one always for you. Should in my excitement forget you will pardon me I know.”

Numbers of letters from Brown to Primus indicate that when visiting they shared a bed along with hugs and kisses. In one letter, Brown told Primus:

- “No kisses is like youres.”

In April 1868, in her late twenties, Addie Brown married Joseph Tines, seemingly for economic security; Brown’s letters suggest that Rebecca Primus remained the love of her life.

Sometime between 1872 and 1874, when she was in her thirties, Rebecca Primus married Charles Thomas.

On the back of an envelope of a letter to Brown, Rebecca Primus wrote, “Addie died at home, January 11, 1870.” Brown was twenty-eight.

Only known photo of Rebecca Primus; with members of the Talcott Street Congregational Church, Hartford, 1922.[5]

6

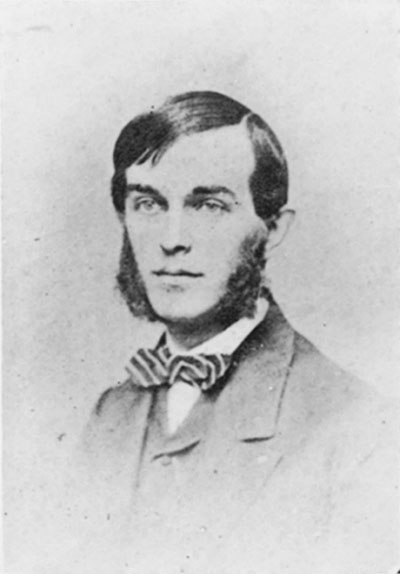

1863: JOHN SAFFORD FISKE

“A heart full of love and longing”

Fiske graduated from Yale in 1863. In 1870, he was tried in the well-publicized Boulton and Park case in London, England, for participating in an international conspiracy to commit “buggery.”

From History of the Class of 1863, Yale College (1905).[6]

Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park were young Englishmen who performed women’s roles in amateur theatricals and began to appear in public dressed as women, thereby attracting the attention of London’s police.

Ernest Boulton as a man and a woman.[7]

Boulton and Park's prosecutors attempted to use their cross-dressing and gender bending as evidence of their involvement in “buggery.”

John Safford Fiske had met Boulton in Edinburgh, fallen in love with him, and sent him several passionate letters, in one of which Fiske wrote:

- “I have a heart full of love and longing.”

These letters were later confiscated by the police and used as evidence of the alleged buggery conspiracy.

At the end of an arduous conspiracy trial, Fiske and all of the accused were found "not guilty."

John Safford Fiske, c. 1879. History of the Class of 1863 Yale College (1905).[8]

7

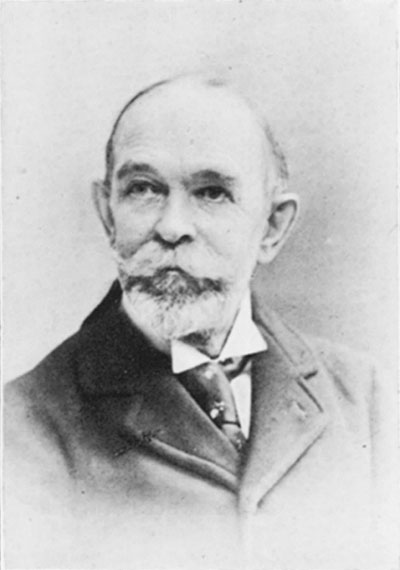

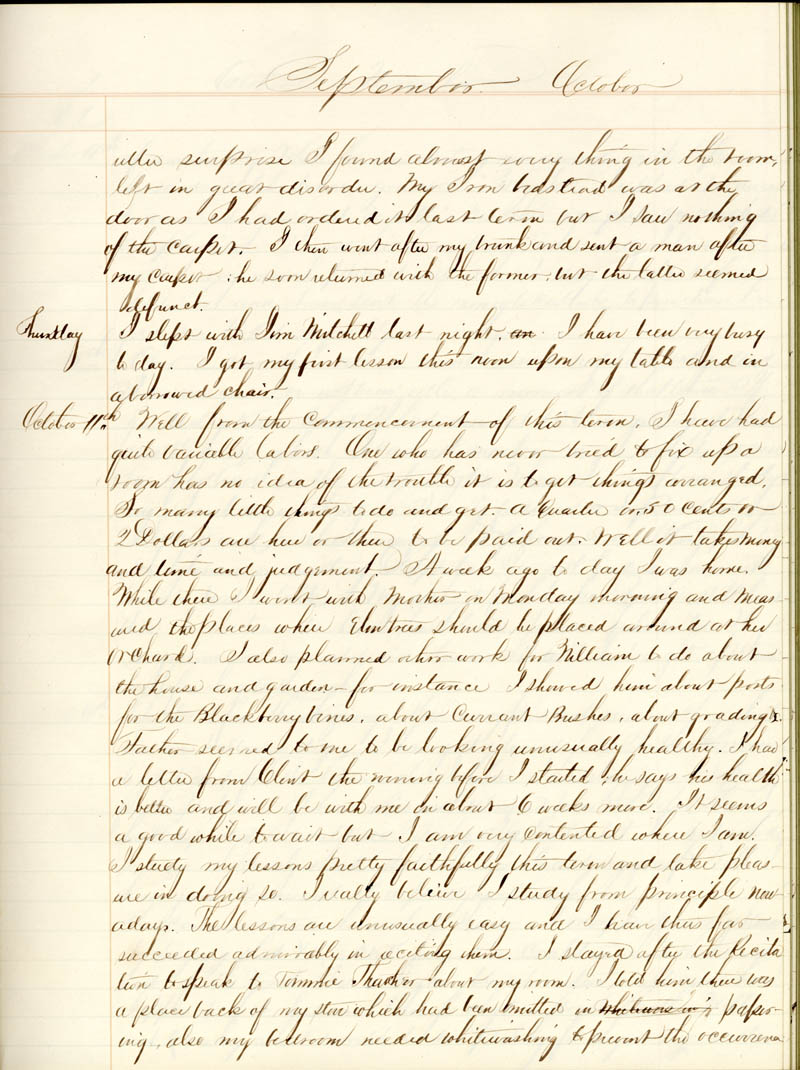

1864: JOHN WILLIAM STERLING AND JAMES ORVILLE BLOSS

“An understanding”

John William Sterling graduated from Yale in 1864 and met James Orville Bloss around 1870. The two lived together in New York City for almost fifty years, until Sterling’s death, in 1918.

In his will, Sterling, a corporate lawyer, left Yale more than fifteen million dollars (the equivalent of more than a hundred and eighty million dollars in 2004).

About Sterling’s intimacy with Bloss, Sterling’s biographer, John Anson Garver (Class of 1875) wrote:

- “an understanding . . . held them together.”

John William Sterling (left) with roommate, Connecticut Hall, July 11, 1863.[9]

While Sterling was still at Yale, in the fall of 1863, his diary reports:

- “Last night I slept with Jim Mitchell an.”

The “an” is crossed out, and the censored thought prevents curious readers from knowing more. Sterling’s bedmate, James Buchanan Mitchell, graduated from Yale in 1863, and, like Sterling, remained a lifelong bachelor.

James Buchanan Mitchell, December 7, 1870.[10]

Sterling's Diary.[11]

Sterling’s will provided that his unmarried sister and unmarried friend Bloss could one day share his mausoleum. Sterling’s married sister was left, after death, to find her own resting place. Sterling thereby constructed his monument as a shrine to single-blessedness, even to marriage resistors.

The idea of Sterling as unromantic and businesslike is belied by a few lines of a poem by Charles Algernon Swinburne that Sterling clipped from the New York Times in 1883 and pasted on the very last page of his commonplace book:

- “Once more I give me body and soul to thee,

- Who hast my soul for ever: cliff and sand

- Recede, and heart to heart once more are we.”

John William Sterling’s mausoleum, Woodlawn Cemetery.[12]

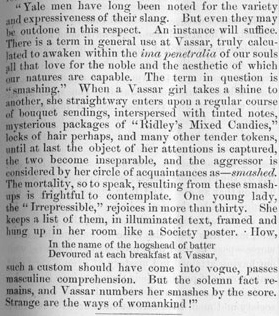

8

December 13, 1873: “SMASHING”

“When a Vassar girl takes a shine to another”

Students of lesbian history have written much about the institution of “smashing” — the intense, sensual intimacies formed by young women at many women’s colleges in the United States and Great Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

A male student’s report in The Yale Courant in December 1873, about a trip to Vassar, discusses smashes:

- “When a Vassar girl takes a shine to another, she straightway enters upon a regular course of bouquet sendings, interspersed with tinted notes, mysterious packages of ‘Ridley’s Mixed Candies,’ locks of hair perhaps, and many other tender tokens, until at last the object of her attentions is captured, the two become inseparable, and the aggressor is considered by her circle of acquaintances as — smashed.”

The writer continued:

- “The mortality, so to speak, resulting from these smashups is frightful to contemplate. One young lady, the ‘Irrepressible,’ rejoices in more than thirty. She keeps a list of them, in illuminated text, framed and hung up in her room like a Society poster.”

The Yale writer concluded:

- “How . . . such a custom should have come into vogue, passes masculine comprehension. But the solemn fact remains, and Vassar numbers her smashes by the score. Strange are the ways of womankind!”

Yale Courant, December 13, 1873.[13]

Laura Johnson Wylie was one of the first three women to receive a Ph.D. in English from Yale, in 1894. The following photograph shows Wylie and Gertrude Buck, Vassar English professors and partners who lived together in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.[14]

9

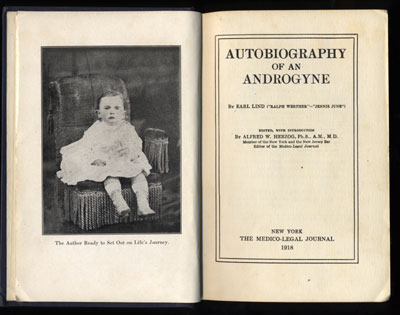

1874: EARL LIND

“To unite for defense against the world’s bitter persecution”

Earl Lind (the pseudonym of a man who also called himself Ralph Werther and Jennie June) wrote in his autobiography that he was born in 1874 in a large village in the Connecticut hills, that he belonged to a Puritan church, and that he attended public school and a boys’ prep school.

Lind went on to become one of the earliest Americans to publish a defense of those he called “androgynes” and “gynanders” (effeminate male homosexuals and masculine lesbians).

Lind wrote that around 1895 he met an effeminate male in a New York City tavern who told him about the formation, by androgynes, of the Cercle Hermaphroditos, “to unite for defense against the world’s bitter persecution.”

Earl Lind as baby.[15]

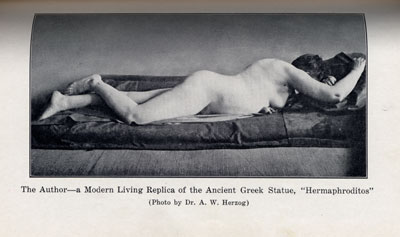

Earl Lind as "a Modern Living Replica of the Ancient Greek Statue, 'Hermaphroditos" (Photo by Dr. A. W. Herzog).[16]

10

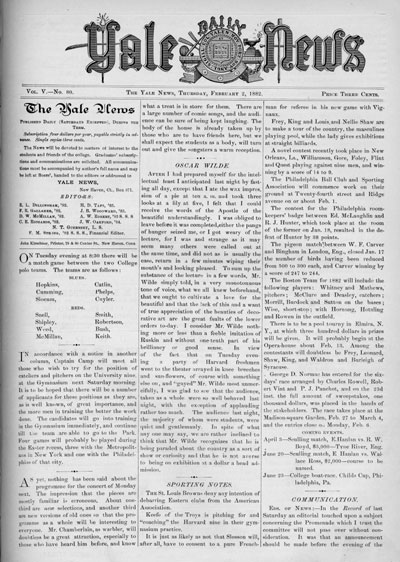

February 1, 1882: OSCAR WILDE

“Why should not Yale college . . . initiate this movement?”

Oscar Wilde spoke in New Haven, at Peck’s Opera House, during his American lecture tour.

Before Wilde’s talk, a writer warned in the Yale Daily News against any demonstration against him like that which had recently occurred at Harvard.

Although Wilde’s “ideas and idiosyncrasies” are “somewhat liable to ridicule,” any “foolish, boyish and disreputable performance . . . would redound to the disgrace of Yale.” For students contemptuous of Wilde’s aestheticism, “the very best way of showing such contempt is by keeping away.”

Six hundred people attended Wilde’s talk on February 1, reported the New Haven Register.

The only Yale student demonstration was “the display of a huge sunflower fan,” and the “wearing of artificial lily boutonnieres by a number of the same group.”

“A round of applause and laughter in which there was a strong tone of derision” saluted Wilde as he came on stage.

Some of Wilde’s lecture was paraphrased:

- “Art had a mission of creating between countries a common intellectual atmosphere which would make men such brothers that they would not go out and slay each other at the bidding of their rulers.”

- “There might be made in America an art made by its people for the delight of its people.”

Wilde asked:

- “Why should not Yale college . . . initiate this movement? A Greek statue placed in your gymnasium should remind you of the artistic sense which moved the Greeks in their culture of physical development.”

In 1895, thirteen years after his U.S. tour, Wilde was found guilty of “gross indecency” with men and sentenced to hard labor in prison.

In 1898, Wilde wrote to the English homosexual-emancipation leader George Ives:

- “Yes, I have no doubt we shall win, but the road is long, and red with monstrous martyrdoms.”

Wilde died in Paris, on November 30, 1900, at the age of 46.

Yale Daily News, February 1, 1892.[17]

References

- ↑ The Code of 1650, being a compilation of the earliest laws and orders of the General Court of Connecticut. Also the Constitution, or civil compact, entered into and adopted by the towns of Windsor, Hartford and Wethersfield, 1638-9. To which is added, some extracts from the laws and judicial proceedings of New-Haven colony, commonly called blue laws. Hartford: S. Andrus and Son, 1845.

- ↑ http://www.outhistory.org/wiki/Legal_case:_Plaine_executed%3B_New_Haven%2C_1646

- ↑ Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. For permission to reproduce contact Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- ↑ Courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

- ↑ Photograph courtesy of the Prudence Crandall Museum. For permission to reproduce contact the Prudence Crandall Museum.

- ↑ Courtesy of Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Yale University Library.

- ↑ Courtesy of the Essex Record Office, Essex, England.

- ↑ Courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University.

- ↑ Photograph courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

- ↑ Photograph courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

- ↑ Photograph courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

- ↑ Photograph by Jesse Reed. For permission to reproduce contact Jesse Reed.

- ↑ From the Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact Yale University Library.

- ↑ Photograph courtesy of Vassar College Archives and Special Collections. For permission to reproduce contact Vassar College Archives.

- ↑ From Earl Lind, Autobiography of an Androgyne (New York: The Medico-Legal Journal, 1918).

- ↑ From: Earl Lind, The Female Impersonators. (New York: The Medico-Legal Journal, 1922).

- ↑ From the collection of the Yale University Library. For permission to reproduce contact the Yale University Library.