Difference between revisions of "New Brunswick's Queer History"

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

| + | [[Image: Edwardbloustein.jpg|thumb|Edward J. Bloustein, President of Rutgers University from 1971-1989]] | ||

In February of 1988, the former President of Rutgers University, Edward J. Bloustein, created the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns which addressed the issues of homosexual students as well as University faculty members. With the early emergence of LGBT students at Rutgers, violence against these students began to surface. These students were harassed, beaten, and socially isolated from their peers. There were not any sources for support, in the classrooms or dormitories, to escape from | In February of 1988, the former President of Rutgers University, Edward J. Bloustein, created the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns which addressed the issues of homosexual students as well as University faculty members. With the early emergence of LGBT students at Rutgers, violence against these students began to surface. These students were harassed, beaten, and socially isolated from their peers. There were not any sources for support, in the classrooms or dormitories, to escape from | ||

the harsh treatment of their fellow classmates. Rutgers faculty members were also experiencing the backlash of non-homosexual support. In a New Jersey court case, five employees, four professors and one dean, tried to obtain health care coverage for themselves and their same sex partners as they were full time working employees like the others. They pleaded their case all the way to the New Jersey Superior Court and judges ruled that, “health benefits only extend to people defined at dependents under the law that established the benefits plan for state employees in 1961. Although the definition included spouses, the judges all agreed that same sex domestic partners could not technically be considered spouses” (Goodnough, 1). These Rutgers professors would be shut out of medical coverage due their homosexual identities. Professors at Rutgers began to experience the homosexual outcast and discrimination that plagued the social and political atmosphere at the university. | the harsh treatment of their fellow classmates. Rutgers faculty members were also experiencing the backlash of non-homosexual support. In a New Jersey court case, five employees, four professors and one dean, tried to obtain health care coverage for themselves and their same sex partners as they were full time working employees like the others. They pleaded their case all the way to the New Jersey Superior Court and judges ruled that, “health benefits only extend to people defined at dependents under the law that established the benefits plan for state employees in 1961. Although the definition included spouses, the judges all agreed that same sex domestic partners could not technically be considered spouses” (Goodnough, 1). These Rutgers professors would be shut out of medical coverage due their homosexual identities. Professors at Rutgers began to experience the homosexual outcast and discrimination that plagued the social and political atmosphere at the university. | ||

| Line 142: | Line 143: | ||

| + | [[Image:Cherylclarke.jpg|thumb|Cheryl Clarke, director of the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns and member of the Rutgers University Department of Women and Gender Studies]] | ||

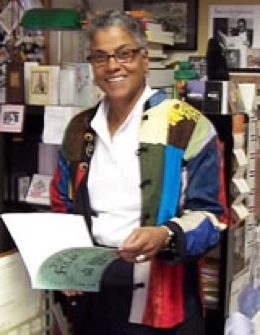

Cheryl Clarke, the director of the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns and member of the Rutgers University Department of Women and Gender Studies, provides great insight into the mass wave of changed that was taking place during this time. Students alongside their professors were dominant force that established change for the Rutgers homosexual political climate. There were some important early events that shaped her political awareness of gay and lesbian issues. Clarke states, “When I was an undergraduate at Howard University from 1965 to 1969, it was a great time of social upheaval and change. It was young people leading this change and a lot of the political movements were lead by blacks” (Interview). These events helped Clarke’s understanding of power and ways in which she could be powerful once she came to Rutgers in 1969. “There was a lot of activism in political change opening up to citizens of color; African Americans and Latinos which I could identify with. There was an interconnection between the gay movement and the women’s movement and here at Rutgers; I saw students and faculty as change agents to make a difference” (Interview). | Cheryl Clarke, the director of the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns and member of the Rutgers University Department of Women and Gender Studies, provides great insight into the mass wave of changed that was taking place during this time. Students alongside their professors were dominant force that established change for the Rutgers homosexual political climate. There were some important early events that shaped her political awareness of gay and lesbian issues. Clarke states, “When I was an undergraduate at Howard University from 1965 to 1969, it was a great time of social upheaval and change. It was young people leading this change and a lot of the political movements were lead by blacks” (Interview). These events helped Clarke’s understanding of power and ways in which she could be powerful once she came to Rutgers in 1969. “There was a lot of activism in political change opening up to citizens of color; African Americans and Latinos which I could identify with. There was an interconnection between the gay movement and the women’s movement and here at Rutgers; I saw students and faculty as change agents to make a difference” (Interview). | ||

| Line 154: | Line 156: | ||

| + | [[Image:Rutgersu.jpg|thumb|Rutgers University]] | ||

Homosexual history at Rutgers University has many important components that demonstrate its progress over time. Gay and lesbian students and faculty endured many inequalities and tried to make their way in a society filled with ignorance during the 1970s. Homosexual organizations, such as the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns, special interests dorms that made the living environments for gays more comfortable and inviting, and clubs that enabled social interaction, made gay life at Rutgers was able to be significantly represented. Rutgers’ course work, lessons in its history, and awareness programming are some of the most important components of homosexual life at this University. Their use of gay and lesbian curriculum helped to bridge the gap between homosexual and heterosexual students. The professors at Rutgers University eased the experiences of lesbian and gays by developing understanding, which is crucial to eliminating ignorance and hate. Together, Rutgers professors and faculty and dedicated students changed the negative stereotype of homosexuals and enabled an outlet for learning and inclusion. | Homosexual history at Rutgers University has many important components that demonstrate its progress over time. Gay and lesbian students and faculty endured many inequalities and tried to make their way in a society filled with ignorance during the 1970s. Homosexual organizations, such as the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns, special interests dorms that made the living environments for gays more comfortable and inviting, and clubs that enabled social interaction, made gay life at Rutgers was able to be significantly represented. Rutgers’ course work, lessons in its history, and awareness programming are some of the most important components of homosexual life at this University. Their use of gay and lesbian curriculum helped to bridge the gap between homosexual and heterosexual students. The professors at Rutgers University eased the experiences of lesbian and gays by developing understanding, which is crucial to eliminating ignorance and hate. Together, Rutgers professors and faculty and dedicated students changed the negative stereotype of homosexuals and enabled an outlet for learning and inclusion. | ||

| Line 160: | Line 163: | ||

== Queer Culture At Rutgers == | == Queer Culture At Rutgers == | ||

| + | [[Image:Rutgersu2.jpg|thumb|Rutgers University, New Brunswick]] | ||

The 1970’s and 1980’s were decades in which contempt for and harassment of queer individuals at Rutgers University, which possessed a largely homophobic population, permeated. The disdainful atmosphere that surrounded queer individuals at Rutgers was so strong, that a faculty member, Susan Cavin, eager to expose the injustices imposed upon students of queer identity, devised the Rutgers Sexual Orientation Survey. This survey served as a catalyst for a reformation of Rutgers policies and attitudes regarding queer individuals. Novel policies were implemented at Rutgers, which proved relatively successful in creating an | The 1970’s and 1980’s were decades in which contempt for and harassment of queer individuals at Rutgers University, which possessed a largely homophobic population, permeated. The disdainful atmosphere that surrounded queer individuals at Rutgers was so strong, that a faculty member, Susan Cavin, eager to expose the injustices imposed upon students of queer identity, devised the Rutgers Sexual Orientation Survey. This survey served as a catalyst for a reformation of Rutgers policies and attitudes regarding queer individuals. Novel policies were implemented at Rutgers, which proved relatively successful in creating an | ||

environment in which queer students would feel comfortable. Nonetheless, despite all the efforts of the Rutgers | environment in which queer students would feel comfortable. Nonetheless, despite all the efforts of the Rutgers | ||

| Line 212: | Line 216: | ||

| + | [[Image:Richardberkowitz.jpg|thumb|Richard Berkowitz]] | ||

Finally, verbal insults and threats of physical violence were not the only forms of abuse Richard witnessed, for when returning to his dorm room on at least three occasions, he discovered his peers had spat on his door. Thus, through Richard’s account of his experience as a homosexual student at Rutgers University, it is obvious that life for the homosexual who courageously came out in the 1970’s and 1980’s was far from pleasant. | Finally, verbal insults and threats of physical violence were not the only forms of abuse Richard witnessed, for when returning to his dorm room on at least three occasions, he discovered his peers had spat on his door. Thus, through Richard’s account of his experience as a homosexual student at Rutgers University, it is obvious that life for the homosexual who courageously came out in the 1970’s and 1980’s was far from pleasant. | ||

| Line 245: | Line 250: | ||

| + | [[Image:Rutgersrotc.jpg|thumb|University Army ROTC building]] | ||

Despite the strides Rutgers University has made in its progression towards a campus that welcomes further integration of queers, there area specific personnel that are associated with the university that do not adhere to the antidiscrimination tactics at Rutgers. For example, The Reserve Officer Training Corps [ROTC], located on College Avenue, is compliant to the United States Department of Defense policy, known as “don’t ask, don’t tell.” This policy ultimately grants the ROTC the authority to reject any students of homosexual orientation. Although the ROTC argues that its practices are federal affairs, instead of university concerns, the university community begs to differ. An ROTC student expresses, | Despite the strides Rutgers University has made in its progression towards a campus that welcomes further integration of queers, there area specific personnel that are associated with the university that do not adhere to the antidiscrimination tactics at Rutgers. For example, The Reserve Officer Training Corps [ROTC], located on College Avenue, is compliant to the United States Department of Defense policy, known as “don’t ask, don’t tell.” This policy ultimately grants the ROTC the authority to reject any students of homosexual orientation. Although the ROTC argues that its practices are federal affairs, instead of university concerns, the university community begs to differ. An ROTC student expresses, | ||

| Line 260: | Line 266: | ||

== Tracing Queer Origins == | == Tracing Queer Origins == | ||

| + | [[Image:Cockettes.jpg|thumb|The Cockettes]] | ||

Today, the social climate for most queer identified students at Rutgers University is relatively open and supportive. There are several active queer organizations, somewhat regular queer events and programs on campus, course offerings that reflect the diverse sexual identities of the Rutgers student body, the Office of Social Justice Education and LGBT Communities, and many supportive students and faculty members to provide acceptance and safe spaces for those who identify as queer. Through the years, the Rutgers queer community has expanded to be more inclusive of the multiple identities in its midst. From its inception to the present there have been issues of inclusiveness, but with each generation the queer community becomes more diverse and welcoming of this diversity. The history of queer organizations at Rutgers and activism in the New Brunswick area has strongly shaped and affected the present day social climate by laying the groundwork for growth and the capacity to expand and diversify. | Today, the social climate for most queer identified students at Rutgers University is relatively open and supportive. There are several active queer organizations, somewhat regular queer events and programs on campus, course offerings that reflect the diverse sexual identities of the Rutgers student body, the Office of Social Justice Education and LGBT Communities, and many supportive students and faculty members to provide acceptance and safe spaces for those who identify as queer. Through the years, the Rutgers queer community has expanded to be more inclusive of the multiple identities in its midst. From its inception to the present there have been issues of inclusiveness, but with each generation the queer community becomes more diverse and welcoming of this diversity. The history of queer organizations at Rutgers and activism in the New Brunswick area has strongly shaped and affected the present day social climate by laying the groundwork for growth and the capacity to expand and diversify. | ||

| Line 266: | Line 273: | ||

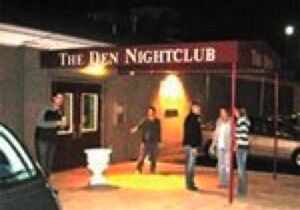

| + | [[Image:Denentrance.jpg|thumb|The entrance to The Den]] | ||

The Rutgers SHL formed in response to the Stonewall riots, a momentous event that kicked off the largest and most public queer movement the country had seen prior to the 1970s. The Stonewall Riots are widely known as a landmark event in the gay liberation movement, but similar events were occurring around the same time in other parts of the country. In the 1960s a New Brunswick, New Jersey club called Manny’s Den was a popular hangout place for homosexuals. In September of 1967 the club was attacked and had its liquor license revoked by the Alcoholic Beverage Commission for the reason of serving “female impersonators” and homosexuals [3]. The club, now called The Den, fought back with the case of One Eleven Liquors, Inc. vs. Division of Alcoholic Beverage Commission and “the arguments brought forth to defend and propel what are now called ‘gay civil rights’ resulted in a ruling that inspired many and was the source for much celebration” [3]. The judge in charge of the decision ruled that “’the Division produced nothing to support any need for continuance of its flat prohibition,’ he went on further to explain that if overtly indecent conduct or other improper acts do not occur, it is not valid to bring charges that are legally unsupportable” [3]. This case in New Brunswick gave rise to the gay community’s strength to fight back and may have even influenced Stonewall. | The Rutgers SHL formed in response to the Stonewall riots, a momentous event that kicked off the largest and most public queer movement the country had seen prior to the 1970s. The Stonewall Riots are widely known as a landmark event in the gay liberation movement, but similar events were occurring around the same time in other parts of the country. In the 1960s a New Brunswick, New Jersey club called Manny’s Den was a popular hangout place for homosexuals. In September of 1967 the club was attacked and had its liquor license revoked by the Alcoholic Beverage Commission for the reason of serving “female impersonators” and homosexuals [3]. The club, now called The Den, fought back with the case of One Eleven Liquors, Inc. vs. Division of Alcoholic Beverage Commission and “the arguments brought forth to defend and propel what are now called ‘gay civil rights’ resulted in a ruling that inspired many and was the source for much celebration” [3]. The judge in charge of the decision ruled that “’the Division produced nothing to support any need for continuance of its flat prohibition,’ he went on further to explain that if overtly indecent conduct or other improper acts do not occur, it is not valid to bring charges that are legally unsupportable” [3]. This case in New Brunswick gave rise to the gay community’s strength to fight back and may have even influenced Stonewall. | ||

| Line 284: | Line 292: | ||

| + | [[Image:BiGLARU.jpg|thumb|BiGLARU logo]] | ||

The name of the former Student Homophile League changed once again in 1991 to include those who identified as bisexual, becoming the Rutgers University Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Alliance. In 1995, the group’s name changed once again to its current name, BiGLARU, the Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Alliance at Rutgers University. Language was added to the group’s 1999 constitution to include those who identify as transgendered, but no changes have been made to the name of the group reflecting that decision, though the subject has been debated in recent years [5]. Also, in 1997, another queer group formed at Rutgers, LLEGO – the LGBTQQ People of Color Alliance at Rutgers University. Both groups continue to be active and play a role in the Rutgers queer community. | The name of the former Student Homophile League changed once again in 1991 to include those who identified as bisexual, becoming the Rutgers University Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Alliance. In 1995, the group’s name changed once again to its current name, BiGLARU, the Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Alliance at Rutgers University. Language was added to the group’s 1999 constitution to include those who identify as transgendered, but no changes have been made to the name of the group reflecting that decision, though the subject has been debated in recent years [5]. Also, in 1997, another queer group formed at Rutgers, LLEGO – the LGBTQQ People of Color Alliance at Rutgers University. Both groups continue to be active and play a role in the Rutgers queer community. | ||

Latest revision as of 12:36, 13 January 2010

Welcome!

This website was created to describe the history of the queer community at Rutgers University and in the New Brunswick, New Jersey area. Each project describes a different aspect of the complicated history, from describing key figures in queer movement, to exploring origins and the overall change over time.

The following topics will be presented:

A Gay History, by Kyle Hartmann (kylehart@eden.rutgers.edu)

How Times Change, by Aaron Lee (aaronlee@eden.rutgers.edu)

University Faculty, by Felisha Blount (feliblou@eden.rutgers.edu)

Queer Culture, by Kerry Conlin (conlon@eden.rutgers.edu)

Tracing Queer Origins, by Alison Gibbons (alisongi@eden.rutgers.edu)

The website was created by Kaitlyn Herthel (kaitlynalyson@gmail.com), under the direction of class instructor Christopher Mitchell (christopher.adam.mitchell@gmail.com).

A Gay History

Rutgers, while in what is now thought of to be a more accepting community, was once a harsh and unsafe place to be gay or lesbian. Joseph Cady, the author of the essay “Notes on Teaching Masculinity and Homosexuality in Literature,” found that, “Despite the accomplishments of the gay liberation movement, there was still no open and reliably safe forum for discussion in the larger university community (at Rutgers the atmosphere remained such that in 1976, two years after I gave the “Homosexuality and Literature” course, a fraternity hung a gay student in effigy on the street outside its house on the “Gay Day” declared by the Student Homophile League)” (158-159 Cady). While this was a problem for the Rutgers gay community it wasn’t until 1981 that Rutgers set up and enforced a nondiscrimination law which among other things encompassed sexual orientation. While this seemed to work for the time this still wasn’t a forum in which people could discuss things such as harassment or bullying. There was really no place that gays and lesbians could go to meet as a group for this or even for a more social setting other than the bars and clubs.

The Den 1950’s to 1990’s

The most popular club around this time was “The Den”. The Den had a long history of being gay friendly and became a gay bar in the late 50’s after a small gay bar opened next to it and the patrons bar -hopped between the two. After this bar closed The Den started to advertise itself as a gay bar and the customers soon followed. The Mack family, the owners of the bar, lived in Greenwich Village in NYC and had a lot of friends who were gay, hence their tolerance of gay people at what was originally not a gay bar. The block was eventually condemned (So that the Johnson and Johnson tower could be built) and The Den was forced to move to Hiram Street near The Frog and The Peace.

It was at this location, according to the current day promoter Scott Silvers, that the State’s Alcohol Beverage Control came in and closed The Den (Silvers). At this time it was illegal for people to congregate together in such a way that others would perceive them as a homosexual. The Den was fined for this but the Mack’s didn’t believe that it was fair so they sued and eventually won. The Den’s webpage records some of that history: “six years later after numerous court challenges the Mac Family eventually won the case against the A.B.C., which set a precedent to allow homosexuals to congregate in public places in the State of New Jersey.

This occurred before Stonewall, in New York City” (The Den). This is something that is interesting because throughout the Tri-State area everyone signifies the gay revolution with Stonewall when in actuality The Den was the first to challenge this law. Scott Silvers said, “ I should also mention that many people say that the news of The Dens triumphant win sent a stirring though the community and probably gave the people in the city the courage to stand up with police raided Stonewall, which prompted the Stonewall Riots” (Silvers).

The Den’s savior came in the form of man the name of David Morris. Morris was a man who loved The Den and as a lawyer came out in order to protect the bar that he was a patron of. He went on to become one of the biggest gay advocates in the State of New Jersey and was a member of the Gay Activist Alliance of Morris County (GAAMC). His passing this year saddened many.

In the late 80’s The Den was forced to move yet again by the city of New Brunswick to make way for the Hiram Square Condominium Complex. The Mack family basically gave up on New Brunswick, thinking that they were being pushed out because of the gay cliental, and moved outside city limits to 700 Hamilton. It was opened again in the early 90’s, after around six months of refurbishing the inside, to huge crowds. There was no money spent on the grand opening, instead relying solely on word of mouth. The thing that attracted a lot of the crowd was the new dance floor, something that they had never had. According to Scott, who started working there as a coat check boy and bar back in the third month after opening, the bar was “packed from day one” (Silvers). Another reason for the high turnout in numbers was that one of the bartenders (who went by the name of Steve Kelso) did a photo shoot for the gay leather magazine Colt. While the bar was previously a crowded place, after the bartenders photo shoot people were coming in from New York to see Kelso, putting the bar at the top of the list of places to be. Kelso went on to become Colt Magazines #1 selling model. Another one of the bars was Todds. Todds was the lesbian bar, “The Den was always the boys bar and Todds was the girls bar” says Silvers, “[Todds] closed [and] reopened as Escape, it was short lived though” (Silvers). Throughout this time a popular place to go after the bar was to “The Wall.” The Wall was a place near the College Ave Train Station where all the gay guys use to go after the bar closed. This was basically a pick up place where you could go to pick someone up if you had no luck at the bar. Sometime around here a group of drunken frat boys “beat the crap out of” a few guys in the early morning (Silvers). Because of this the pick-up location moved to Seminary Place.

Michael Corey 1978 to 1985

Michael Corey entered into the pharmacy program at Rutgers in 1978 and decided to live on College Avenue. He dormed in the Frelinghuysen Dorm which he felt was better than having to live on Busch as far as being able to be himself. He didn’t want to come out but at the same time was trying to explore his new freedom. He says that “The biggest worries were social stigma, family acceptance, being ostracized, getting beat up, mocked and abused and, of course, an occasional case of the clap. To a very large degree (as far as I knew), nobody knew I was queer and I spent a lot of time doing my best to hide it” (Corey). He did say that the best part about living in the dorms was being able to check out the guys on the floor when you took a shower.

Michael remembers the name calling around campus - “fag” or “queer” were said in such a way that wasn’t just another insult, it meant something. The college avenue campus was usually pretty tolerant towards the gay population but these words could sometimes be heard around “the quad” on College Avenue or some of the dorms that had balconies after some alcohol was added. He also notes that the Livingston Quad was pretty bad due to the “radical unrest” at the time.

Michael spent a lot of his time over the next few years trying to keep up with the pharmacy programs regimented course schedule. A popular hangout for him to relax was The Den. He recalls:

- “The Den was your basic local / regional gay bar. It was in the slum section of town near the end of Route 18 (before it was extended over to Piscataway). This was also close to the slum section of town where the Projects were build. The bar was split into 3 areas. . . a small/cramped bar area when you walked in (checking you coat with Mrs C) and then drooling over Peter at the bar; bathrooms were in the back and small a trough and 1-2 stalls (with varying uses depending upon how busy the place was); a small outdoor area with some tables and plants in a fenced-in area; and a medium sized dancefloor in a separate room” (Corey).

The Den was a place where Michael could go to relax. He ended up going there with his friends a lot of the time, sometimes for holidays such as Halloween, in which he won a trophy for a costume. Around this time though being gay wasn’t as safe as it is today. After a few robberies and a few muggings that occurred as guys were leaving the bar, it became commonplace for people to leave in pairs or groups. And while he doesn’t say that the police were receptive, they weren’t dismissive either.

The popularity of the different types of places that men went to cruise are also a part of this history. Places like “The Wall,” which was also known for mild amounts of gay prostitution, and the Rutgers Library were just some of these places. He explained,

- “The wall was an elevated area where there was a cement retaining wall. Guys would meet by the wall and then could take a little action in mall area behind plants or inside one of the school buildings if they were open. We'd also ride our bikes over later in the evenings and see who was around or who might do a drive by. Older guys would ride past in their cars riding very slow and with a window down to check out who might be of interest. It sounds very NYC streetcorner whores and in some cases, it was. The College Ave library stacks and men's rooms were pretty standard, but they were also notorious so at times it had the potential to be hostile in addition to somewhat exciting. The College Ave Gym also had possibilities if you were working out or playing a sport (not me). There was also the potential to meet other guys in the darkened areas around the College Ave Quad. . . it was a bit safer area if you lived there” (Corey).

These places allowed for men to meet and hook up. While they didn’t necessarily allow men to be 100% safe or 100% out, it provided a common ground where you could find someone like you and be able to hook up. Richard Berkowitz in an interview after his lecture also mentions “The Wall” and how he and a friend of his would frequent this area looking for guys to hook up with (Berkowitz). While he doesn’t say directly that he partook in the prostitution in this area, with the reputation of The Wall and Berkowitz’s accounts of his twenties it might not be that hard to assume what happened.

The rest of his Michaels years at Rutgers were marked by meeting and eventually rooming with a number of different gays and lesbians, coming out to friends, exploring his sexuality with other men (sometimes more than one at once) and eventually graduating.

Change at Rutgers 1998 to 1992

While the clubs, specifically The Den, allowed for a meeting place socially, there was still no place to meet to talk about the problems of the college. It was because of this, among other things, that the University decided to set up a committee to battle these types of attacks on the University’s gay students. “In reaction to homophobic graffiti and harassment, the university in 1988 created the Select Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns” (Wall Street Journal). This was a much needed step that would help to bring the harassment and mistreatment of gay students at Rutgers to lower levels.

Jeff Van (1994) a student at Rutgers University “says, he acted like his Connecticut prep-school friends. He dated girls, and he talked about them with his dad, man to man. Now a college sophomore [article from 1992], he would rather put on a dress and go off the gay and lesbian dance. (He told the bridal salon the dress was for Halloween.) He wears a rainbow flag on his backpack to make a point of his homosexuality.” Jeff goes on to talk about how at an interfraternity meeting that was intended to talk about the negative aspects of stereotypes, he went up against the Greeks saying: “I’m sick of asking people’s permission to be gay.” While Jeff feels safe enough to go to the gay and lesbian dance, others might feel that their masculinity is being challenged by this (Wall Street Journal). While Van recognizes that he is fighting for his freedom and rights now that once he starts looking for a job his activism will probably be left out of his resume for fear of finding a job.

Another gay student James Dale (student in the early 1990’s) was the subject of a controversy after a newspaper ran article on a seminar taking place on the needs of lesbians and gay youth that he took part in. Because of this he was thrown out of the Boy Scout troop that he was an assistant scoutmaster of. While this was not directly linked to Rutgers it marks the beginning of change. Men were now starting to feel more comfortable about their sexuality and now were willing to stand up for it. Students started to feel that they could be themselves and come out not only on campus but in the real world. “Mr. Dale has been successful at merging his two worlds. After coming out his sophomore year at Rutgers, he told his mother and -- eventually -- his father, a former Army colonel. Last year [1991], both parents marched in the national Gay Pride parade in Washington” (Wall Street Journal). While this could be attributed to changing times and gay men being more accepted in general this also most likely has to do with the fact that Rutgers, after realizing that there was a problem that could no longer go unnoticed, set up a committee in order to deal with this.

What eventually happened was, “in reaction to homophobic graffiti and harassment, the university in 1988 created the Select Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns. It is chaired by James D. Anderson, a gay university administrator. Its membership also includes faculty, students and staff, even the campus police chief” (Wall Street Journal). While this worked for many years it was interesting to see how the university seemed to change its mind a few years later. Rutgers supposedly started to offer benefits to sole domestic partners or gay faculty members but when a few members tried to collect on health insurance and health care they were turned down. While they allowed other benefits, such as access to the gym, family housing, and time off for bereavement, they were not allowing what would most likely cost them the most, insurance and health care. Due to this, five gay and lesbian employees at Rutgers filed suit in 1993 in Middlesex Superior Court. Among these was James D. Anderson who ended up leaving the university because of this (Queer Resource Directory).

While Rutgers over the years has recognized the gay population and tried help ensure the safety and well being of their students and staff, they have just recently in the past twenty years put up real measures to do this. By creating a Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns they set up an actual body to look over what was going on at the college. Partner benefits are starting but they need to go further. The most telling sign that the temperature of the college is changing though is how students have gone from being afraid to come out, to coming out at college but not in the real world, to finally going up against the State for being let go from the Boy Scouts. A rock during all of this for the gays to hold on to is The Den. Being run for over fifty years as a gay bar, The Den has provided a social gathering point for the gay community and continues to till this day.

How Times Change

Until quite recently it was illegal to be gay in the United States. That changed with the federal repeal of sodomy law. College has always been a haven for those among us who are intellectuals or lead alternative lifestyles. New Brunswick has a history which has been rich with Queer life. However, if one were to look at Rutgers and New Brunswick today, it is a very different place when compared to how it was for those who came before us. Living on campus is a wonderful experience for many people. It is an opportunity to find yourself away from those who knew you; like your parents and high school friends. For queer people, it serves the same purpose. Although, for queer people it is often a more important time of self-discovery, because in college an individual finds himself or herself or zirself in an environment where sexuality and gender are things to be studied and not viewed as strict constants in our lives. However, what if these important psychological processes are interrupted by a homophobic or transphobic roommate? What if you cannot live with a person who shares the same gender identity that you do? All of these are obstacles which LGBT people have to overcome when they are living on campus. How has living on campus changed? How has it stayed the same? Rutgers appears to be following a national trend that I have noticed. It is easier to be gay anywhere, so queer people tend to not congregate together as much as they have in the past. The 1960’s was the beginnings of a sexual liberation for many people, for queer people it was the beginning of a more gay mainstream liberation which came to a head in 1969 in New York city. For Rutgers, the story begins much earlier. However, this investigation picks it up in 1972 in Wessels dormitory with Walter’s history. Walter lived in Wessels for his freshman and sophomore years of college. In that day, some rooms in Wessels had three people to a room. Walter’s two roommates tried to force him to leave the room because he was gay. On another occasion, one of his roommates who was also gay and training to become a lawyer, asked Walter to sign an affidavit stating that he was not gay, nor had they ever touched each other. Walter says he later saw this roommate casting multiple ballots for himself in a student government election. Walter continued saying that overall he did not feel that he could be open about his sexuality. During his freshman year while he was still closeted, he began exchanging letters with someone from the Rutgers Homophile league. Eventually the other student he was writing to, named Jim, phoned him and they spoke briefly.

Walter’s living situation later changed and he went to live in a single in Brett Hall. He also wrote for the Rutgers newspaper, The Targum, and later became its editor. He did say that he loved being in college. After Walter left Rutgers, he said he went back in the closet. When I asked him why, he responded with “would you tell someone that you were transgender after you’re out of school?” and I replied, “Ha ha, maybe in 20 years.” We both laughed but I realized the gravity of both of our situations. His attitude seems to reflect an attitude of that time saying that, in the end you can only depend on yourself (Walter). When I asked him what he thought the biggest difference was for queer people of my generation, he said the biggest difference was that now you could look on TV and see people that were like you(Walter). There was no Will and Grace during his time. The biggest names in the gay community were porn stars.

Richard Berkowitz was another Rutgers Student who went to school during the same time as Walter. In fact, they met when Richard came into the Targum office and wanted to write an article about an interview that Dick Cavett was doing with Katherine Hepburn(26). Richard lived in Hardenbergh Hall, one of the dorms near the Raritan River. In his book, Stayin’ Alive, Richard recalls feeling embarrassed while walking into the office and seeing the receptionist reading a book called Lesbian Nation. After writing the article, Walter began calling Richard quite frequently. In that time, rooms did not have private phones, so someone on your floor would pick up the phone and call out who the phone call was for. Walter kept calling so frequently that Richard’s floormates eventually confronted him about, “that flaming fag from the Targum” (Berkowitz, 27). Richard went and hid in his room for fear of violence. He eventually moved off campus because hearing the people that lived around him calling him a faggot and laughing at him drove him to the edge of Hardenbergh’s rooftop one day. Richard also made his living by hustling at some gay cruising spots which were on campus. The two main pick up places were Kirkpatrick Chapel --which is only a short walk away from the main residence hall area on college avenue-- and the Seminary wall which is an even shorter walk. Walter recalls a time where both Richard and he were trying to pick up men at the wall around Kirkpatrick Chapel and someone drove up next to them and threw water in Richard’s face.

It turns out Richard’s and Walter’s fears and unease were not unfounded. The Rutgers Homophile league occasionally ran an event they called Blue Jeans Day. The purpose of the event was to show how arbitrary it was to categorize someone solely based on their sexual orientation by planning to “record” all students that day who wore blue jeans as homosexual (Nichols 66). This event ran several times over the years, the first being in 1974, and another in 1975. In 1975, a fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) hung an effigy that bore a sign that read “The only good gay is a dead gay—back to your closets homos”(qtd. Nichols 67). The crowning piece of the effigy was a pool cue stuck through the effigy’s chest (Berkowitz 35). In 1978, the Homophile league, now re-named Rutgers Gay Alliance held another blue jeans day, to which DKE responded with another effigy hanging from a second story window, with its arms outstretched as if it were being crucified(Nichols 69). In 1979, another Blue Jeans day was held and instead of an effigy, they hung a sign out the window reading, “Sodomy is a pain in the ass” and “Anita—Deke loves you” (Nichols 70). Eventually in 1980 DKE was placed on probation, and was later kicked off campus for a violating their probation(Nichols 76). According to Stayin’ Alive, in 1974 Howard Crosby was gaybashed and suffered severe head trauma(34). It seems that violence and threats were almost commonplace for queer students living on campus and went on uncontested for quite a few years.

One particular dormitory on college avenue has a reputation for being what Junot Diaz called, “home of all the weirdos and losers and freaks and fem-bots”(170). Junot Diaz lived in Demarest Hall and was a former Creative Writing Section Leader. The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries called Demarest, “a hot bed of homosexuality” (Nichols, 79). Demarest was originally a freshman dorm before 1950, when it became the dorm for RU football players. The original football stadium was located where the college avenue parking deck now stands today. In the 1960’s it became an honors dorm, and in 1966 the dorm’s residents created what are known as Special Interest Sections, which are discussion groups that run weekly and center around an academic topic (The History Lesson). Demarest appears to have had quite an interesting history with regard to non-normative culture. Many of the leaders of the Homophile league, and that club’s offspring have lived in Demarest. A woman named Wilhite, who was involved with Rutgers Gay Alliance, and also in the lodging of complaints with DKE lived in Demarest(Nichols 78-81). Demarest Hall also had an underground Women’s Studies section, and a small group of feminists formed CAFT (College Avenue Femminist Terrorists)(Nichols 79). A current resident, Danny, recalls speaking to an alumna of the women’s studies section and learning that they held a section on “How to Queef”(Danny). CAFT also was notorious for doing things like spilling ammonia in Scott Hall when a pornographic film was being shown in one of the classrooms. One fraternity was showing pornographic films at a fundraiser to try to make money, and CAFT staged a bomb threat all in order to combat sexism. (Nichols 79). Though, during 1979-1981 when Wilhite was a resident, not all in Demarest was queer friendly. Some of the straight members of Demarest resented the building having the reputation of the gay dorm, and wrote profanity on some people’s doors (Nichols 80).

Demarest today has some similar traits to the ones it had in the 1970s and 1980’s. It still prides itself on tolerance and acceptance. Some residents muse that the construction of the building—the narrow halls and small rooms as well as the infamous stoop-- forces you to speak to essentially everyone in the building. A strong sense of community is instilled in new residents upon their first days living in the building by older residents who want to share their experiences with incoming students. In the early 1990’s, Demarest formed its first LGB Interest Section. A former resident named Eric, surmises that the group’s founding was “to give academic merit to a safe space…and to give solidarity to that group of people.” Of course, Demarest cannot advertize itself as a safe space, because that would imply that other buildings on campus are not safe spaces for queer people. The LGB interest section eventually added a letter, a T for transgender, sometime during the 1990’s and in the very late 90’s it underwent another name change and became known as Queer Studies(Eric). Eric says the name change was due to the term queer at the time having less stigma attached to it, and there were multiple Queer activists in Demarest. The first section, or discussion of the year was Coming Out Stories, which remained a tradition until the section’s membership started dwindling to around 5-6 people in 2005-2006. Eric and another resident who lead the section named Paul, changed the name to Sex, Sexuality and Gender in the year 2006. Eric says the name change came about because of dwindling membership, and the Coming Out Stories tradition deterred straight allies from joining and sharing their experiences. Danny remembers the new section blossoming through an increase in participation. “Even though the focus ultimately changed away from queer, the diversity of opinion in section and increase in membership more than made up for it.”

Some of the more peculiar aspects of Demarest that are around today include an unofficial coed bathroom policy created by the residents, which probably dates back to the 1970’s(Eric). Two years ago Demarest underwent a remodel, and previously because the building housed football players, all the bathrooms—men’s and women’s—had urinals in them. The sides of the building where there men’s and women’s rooms were located would switch after each semester. Occasionally, because this practice is so common to “Returners”, or residents who are returning to live in Demarest for another year, newcomers sometimes are not informed of this policy and are sometimes frightened when they discover a member of the opposite sex in their restroom. Eric remembers before he was even living in the building, he spent the night here as a high school senior and walked into the men’s room and saw a woman in there. He goes onto explain that this is not a “pervy thing” and I have not found any incidences of inappropriateness in my experiences in the building, or in my research. Many residents ask what the difference would be if the bathrooms were sex segregated, as people living on the side of the building where their appropriate bathroom is not there, would have walk around the halls in a towel in order to shower. There have been recent movements to make the coed bathrooms an official dorm policy, but those were rejected. Though, the residents’ concerns may have been heard because in the recent remodel, none of the bathrooms were fitted with urinals, and the only difference between the two is the sign outside the door on the wall. However, residents often like to rip the signs off the wall, and this year, someone drew a penis on the woman in the WOMEN’S sign. Eric shared with me some of the other events that occurred on his first night in Demarest. He was at a CAP (College Avenue Players) party and they were playing spin the bottle, and it landed on another man, and this particular guy “freaked out”, Eric said, “it is strange to see such acceptance inside a building and outside; not”(Eric). Many people within the building do not have problems with having a LGBT identified roommate, and are supportive even if there is a declining queer population in the building itself. There was also another movement to have gender neutral housing in Demarest, and while that request was declined, residents did an unofficial room switch anyway so that people of the same sex were roommates. It was all set to happen, when the residents, who were living in the basement rooms, found cockroaches in their rooms and decided to move out(Eric).

Recently, it seems that many queer groups are becoming smaller and smaller. Perhaps it is because it simply is easier to be gay anywhere now. Eric muses that, most of the people who go to Rutgers are white upper-middle class people, and those of whom identify somewhere on the spectrum often do not have to go through as much pain with regards to their sexuality and are able to blend into mainstream culture. There is also a rising sentiment that a queer person doesn’t just only need queer friends anymore. Being out still has an explicit value, in the fact that it offers some people a chance to see healthy individuals who they may share an identity with, but as Walter said in my interview with him, “the biggest difference between your generation and mine is that you can look on the TV and see gay people… we had no Will and Grace in my day”. As a transgender person, I have not encountered any problems living in a dorm. Today, trans people are viewed very much like gay people were viewed in the time before 1990. If I can live freely, then I would imagine that most gay or lesbian people would be able to live elsewhere on campus and for the most part feel safe. I’m not sure that they could be out, just as I am not sure I could be out in another dorm, but I imagine with the right support system a person could manage. Rutgers adopted a policy prohibiting discrimination and harassment which includes sexual orientation, sex, gender identity and gender expression and was last updated last year(TLPI: College and University Policies). Rutgers today is in many ways a different place than it was years ago. This generation of Queer people is different from previous generations of LGBT identified people. What is happening in college dormitories is very indicative of how LGBT people are viewed in society today. Perhaps Demarest is not a great barometer, because it offers itself as a haven for those students who really need a support system and a place to find themselves more than other dorms do. As queer membership in LGBT oriented clubs decline I think a question we have to ask ourselves is why this is happening? Being mainstream is tempting, but I think it is also important to realize that unless there are some people who are willing to stand behind the most vulnerable of minorities, we have lost sight of what equality really is.

Rutgers University Faculty

Homosexual history at Rutgers University has many important components that demonstrate its change over time. Gay and lesbian students and faculty endured many inequalities and tried to live in an environment that cast them as inferior. Subsequently, through numerous beneficial outlets such as organizations promoting awareness and tolerance, special interests dorms, and clubs that enabled social interaction, gay life at Rutgers was able to be significantly represented. One of the most important components of homosexual life at this University was Rutgers’ course work and lessons in its history. Gay and lesbian professors and their efforts to educate students on homosexuality, helped to create a positive discourse of gay and lesbian students. Their use of course work helped to bridge the gap between homosexual and heterosexual students. The professors at Rutgers University eased the experiences of lesbian and gays by developing understanding, which is crucial to alleviating intolerance. There were numerous important components to the gay community in New Brunswick, but the homosexual professors at Rutgers University lay the foundation for open gay study and acceptance at its collegiate level.

In February of 1988, the former President of Rutgers University, Edward J. Bloustein, created the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns which addressed the issues of homosexual students as well as University faculty members. With the early emergence of LGBT students at Rutgers, violence against these students began to surface. These students were harassed, beaten, and socially isolated from their peers. There were not any sources for support, in the classrooms or dormitories, to escape from the harsh treatment of their fellow classmates. Rutgers faculty members were also experiencing the backlash of non-homosexual support. In a New Jersey court case, five employees, four professors and one dean, tried to obtain health care coverage for themselves and their same sex partners as they were full time working employees like the others. They pleaded their case all the way to the New Jersey Superior Court and judges ruled that, “health benefits only extend to people defined at dependents under the law that established the benefits plan for state employees in 1961. Although the definition included spouses, the judges all agreed that same sex domestic partners could not technically be considered spouses” (Goodnough, 1). These Rutgers professors would be shut out of medical coverage due their homosexual identities. Professors at Rutgers began to experience the homosexual outcast and discrimination that plagued the social and political atmosphere at the university.

To ease tensions, President Bloustein instructed that all the campuses, New Brunswick, Newark, and Camden, to select a leader that would assume responsibility for lesbian-gay concerns. These representatives would be in charge of providing student focused education in each college, school, or unit to the issues of lesbian-gay undergraduates. The leaders would assist students in resolving problems, promoting general awareness, sponsoring programs to reduce homophobia and heterosexism, and making appropriate referrals for services and any special help (Nieberding, 85). Since 1988, the network of representatives includes faculty members, members from religious communities, and staff in areas other than student affairs. As the issues of bisexual students has become more public, representatives have also extended themselves to students who choose to identify as bisexual (Nieberding, 86). This major advancement for gay and lesbian interests would help to ease their apprehension and fear ridicule. These professors and leaders had a crucial role in setting the tone for a positive, homosexual social environment at Rutgers. In the book, Gender and Teaching, by Frances Maher and Janie Ward, state, “Many case studies illustrate how sexism and homophobia operate and interact with conventional stereotypic expectations of boys and girls in educational environments and many times, it is the professors responsibility for the way students treat each other” (Maher and Ward, 37). Rutgers professors had a pivotal role in leading the movement for a positive change in homosexual treatment.

There were three significant issues that the committee needed to address immediately. One of the many initiatives recommended by the committee was extending health insurance coverage to the partners of homosexual employees and giving gay couples access to married students housing. To ensure a timely implementation of the proposed changes, the report called for the creation of a professionally staffed office at Rutgers devoted solely to homosexual concerns (Hendrie, 1). This advancement was extremely crucial to the development of the gay community at Rutgers. The office would set the framework for the promotion of homosexual awareness and education. The committee called for a series of steps to meet the needs of homosexual students, including the creation of lounges and resource centers and the establishment of a dormitory devoted to creating a non-racist, non sexist, non-homophobic environment. The committee devised a thorough plan for exposing incoming students, fraternities, sororities, faculty, administrators, and other staff, to workshops aimed at fostering sensitivity to gay concerns. Most importantly, the committed set the outline for incorporating the experience of gays and lesbians into course curricula and encouraging research into issues of concern to them (Hendrie, 1).

Cheryl Clarke, the director of the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns and member of the Rutgers University Department of Women and Gender Studies, provides great insight into the mass wave of changed that was taking place during this time. Students alongside their professors were dominant force that established change for the Rutgers homosexual political climate. There were some important early events that shaped her political awareness of gay and lesbian issues. Clarke states, “When I was an undergraduate at Howard University from 1965 to 1969, it was a great time of social upheaval and change. It was young people leading this change and a lot of the political movements were lead by blacks” (Interview). These events helped Clarke’s understanding of power and ways in which she could be powerful once she came to Rutgers in 1969. “There was a lot of activism in political change opening up to citizens of color; African Americans and Latinos which I could identify with. There was an interconnection between the gay movement and the women’s movement and here at Rutgers; I saw students and faculty as change agents to make a difference” (Interview).

There were several instances that enabled Cheryl Clarke to become aware of lesbian feminism and its impact on her identity. She first became aware of lesbian feminism through a lesbian friend who had died of the AIDS virus in 1973. This is when she first recognized the movement and became aware of what it promoted. What deepened her understanding on this arena was a conference which she attended discussing Gay Liberation. Clarke explains, “There were four or five black lesbians talking about sex and gender, basically about being gay, black women. They were strong confident and natural born leaders. This was the first group of women I saw who had a gender analysis and I could identify with them as a black gay women. In addition to that experience, I also did a numerous amount of reading including gay literature and black literature by women. These also were great teachers” (Interview). Her identity as an African American woman also greatly impacted her experience and created an additional dynamic to her knowledge and understanding. Cheryl explains, “This is the way I’ve always been, having a black identity and lesbian identity. These were my core identities and were always very important. It is interesting to be a black feminist advocating for black feminism and lesbianism. Sometimes it is more necessary to be black and push that to the forefront and other times it is more important to be a feminist. I consider being black and lesbian as a form of politics” (Interview).

During the 1970s and 1980s, there were serious challenges faced by the lesbian feminist community. Cheryl Clarke affirms that obtaining recognition was one of the most serious challenges living as a lesbian during this period. Cheryl states, “Everyone was gay then, but it was important to change people’s stereotypes. Lesbians started to call themselves lesbians because of sexism within the gay community itself. Sometimes they were just as sexist as heterosexuals. It was about shattering the stereotype and changing policy that had to do with restricting lesbians” (Interview). At the time, there was a lot of controversy over lesbian motherhood and children could be taken away from their lesbian parents. Cheryl adds that, “Lesbians also had to not only gain recognition in the gay movement but also the women’s movement. The face of feminism was white, straight and suburban and this does not represent all of us. African American women have been in the movement for a long time and recognition was so important” (Interview). Writer and Rutgers faculty member, Charlotte Bunch, explains that it was imperative to have an interconnection between women to gain this recognition and overcome stereotypes. She explains, “If women did not make a commitment to each other, which includes sexual love we deny ourselves the love and value traditionally given to men. We accept our second class status. When women do give primary energies to other women, then it is possible to concentrate fully on building a movement for our liberation” (Myron and Bunch, 30). It was important for lesbian liberation to have a strong commitment between all kinds of women to truly gain recognition and acceptance.

When Cheryl Clarke came to Rutgers, there was a positive atmosphere regarding homosexuals and their advocacy for change. “New Brunswick was very supportive of gay and lesbian endeavors. Students themselves were also lending support to those who needed it. We have had an office for LGBT since 1992, but that doesn’t mean that things still do not occur. I remember a homosexual boy was tragically hanged by members of a fraternity and all the deans and officials took action against it. The fraternity was removed from campus and there were serious consequences and this put into perspective that there are places in which professors and faculty will not be. It was a professor and student collaborative effort, but students are the ones who live here and deal with pressures we wouldn’t face. In many ways, students themselves had to take the initiative to educate and provide awareness. Cheryl Clarke believes that the idea of community is very important to gay and lesbian education and acceptance. It plays a key role in the learning and living environment at Rutgers University. The LGBT office seeks to build this community and set the tone for more harmony amongst homosexual and heterosexual students. Clarke says, “The LGBT office’s most important roles are advising and coordinating a core curricula for gay and lesbian course work and maintaining a quality of education for students. It is full throttle support for LGBT students. Some of the things we are developing are a Rainbow Graduation which will recognize gay and lesbian graduates at Rutgers. We also hold “Coming Out Parades” to celebrate those identifying as homosexual. Our basic mission is education. We are strong advocates for the equal treatment of LGBT students and their acceptance in all elements, both academic and social, in student life at Rutgers University.”

Homosexual history at Rutgers University has many important components that demonstrate its progress over time. Gay and lesbian students and faculty endured many inequalities and tried to make their way in a society filled with ignorance during the 1970s. Homosexual organizations, such as the President's Select Committee for Lesbian-Gay Concerns, special interests dorms that made the living environments for gays more comfortable and inviting, and clubs that enabled social interaction, made gay life at Rutgers was able to be significantly represented. Rutgers’ course work, lessons in its history, and awareness programming are some of the most important components of homosexual life at this University. Their use of gay and lesbian curriculum helped to bridge the gap between homosexual and heterosexual students. The professors at Rutgers University eased the experiences of lesbian and gays by developing understanding, which is crucial to eliminating ignorance and hate. Together, Rutgers professors and faculty and dedicated students changed the negative stereotype of homosexuals and enabled an outlet for learning and inclusion.

Queer Culture At Rutgers

The 1970’s and 1980’s were decades in which contempt for and harassment of queer individuals at Rutgers University, which possessed a largely homophobic population, permeated. The disdainful atmosphere that surrounded queer individuals at Rutgers was so strong, that a faculty member, Susan Cavin, eager to expose the injustices imposed upon students of queer identity, devised the Rutgers Sexual Orientation Survey. This survey served as a catalyst for a reformation of Rutgers policies and attitudes regarding queer individuals. Novel policies were implemented at Rutgers, which proved relatively successful in creating an environment in which queer students would feel comfortable. Nonetheless, despite all the efforts of the Rutgers community, there will always be select individuals whose negative perceptions of queer individuals cannot be modified.

Throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s, homosexual students who resided at Rutgers University possessed two choices: to internalize their homosexuality and thus, live a covert existence or externalize their homosexuality and risk humiliation or degradation. An individual who opted to maintain an inconspicuous homosexuality often did so by adopting specific courses of action, which would reduce the likelihood that any member of the Rutgers community would discover his or her homosexuality. Particularly, the homosexual student would avoid areas on campus where homophobia permeated, such at Fraternity Row. Moreover, a gay student would carefully select clothing and behavior that would not lead anyone to suspect his or her homosexuality, such as, avoidance of flamboyant apparel or affection towards same sex individuals. Finally, those homosexual students extremely adamant about disguising their sexuality would go as far as relocating to an off campus residence (Cavin, p. 4).

Those students who displayed their homosexuality, even if merely in a discreet manner, often underwent severe victimization by homophobic members of the Rutgers community. According to the Rutgers Sexual Orientation Survey, out of the ninety five students surveyed in 1987, fifty-three percent of them reported experiencing unfair treatment on campus. The most common ways in which perpetrators created a hostile campus climate that instilled fear and anxiety in homosexual students were verbal insults, threats of physical violence, chasing, objects thrown, sexual assault, damaged property, beatings, assault with a weapon, and spitting [these fall on a continuum with verbal assaults comprising a majority of injustices and spitting the minority] (Cavin, p. 15).

| Injustice | Rate of Occurrence |

|---|---|

| Verbal Insult | 55% |

| Threats of Physical Violence | 16% |

| Chasing | 18% |

| Objects Thrown | 12% |

| Sexual Assault | 8% |

| Damaged Property | 6% |

| Beatings | 4% |

| Assault With A Weapon | 2% |

| Spitting | 1% |

An example of a gay student who was the target of verbal insults was Richard Berkowitz. While at Rutgers University, Richard Berkowitz’s peers began to suspect him of being gay when Walter from the Targum, who was also a homosexual, repeatedly attempted to contact Richard. When Richard denied his homosexuality, one student, Dan, said, “even though you’re a low life cock sucking faggot, you have enough sense to try and hide it (Berkowitz, p. 28).”

Additionally, while Richard was walking near Fraternity Row one day, he witnessed the sight of an effigy being lynched on a tree outside of The Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity house. Next to the tree was a sign that said, “the only good gay is a dead gay (Berkowitz, p. 35).” This morbid act, which demonstrated the evident contempt towards homosexuals at Rutgers, can be considered a threat of physical violence.

Finally, verbal insults and threats of physical violence were not the only forms of abuse Richard witnessed, for when returning to his dorm room on at least three occasions, he discovered his peers had spat on his door. Thus, through Richard’s account of his experience as a homosexual student at Rutgers University, it is obvious that life for the homosexual who courageously came out in the 1970’s and 1980’s was far from pleasant.

Susan Cavin’s Rutgers Sexual Orientation Survey also provides numerous instances in which homosexual students were harassed for their sexual orientation. For example, upon returning to his dorm, a homosexual student discovered a disparaging mark on his door which said, “AIDS Victim (Cavin, p. 2).” Furthermore, on another occasion, an individual was assaulted by a peer who was carrying a weapon. While departing from class, this student was approached by a male peer, who held a gun up to her back and urged her to answer his question, “you know I am not a homosexual, right?” Additionally, while on the bus ride back from her class, a student began to demonstrate affection towards her same sex lover [the couple was seen kissing]. Once the bus driver caught a glimpse of this affection, he pulled the bus over, opened the door, and forced the couple off the bus saying, “not on my bus (Cavin, p. 24).” Overall, the Sexual Orientation Survey demonstrates that homosexual students at Rutgers were often the targets of discrimination and persecution, which resulted in an apprehensive existence on campus for such individuals.

In the midst of this immense disdain directed towards homosexuals at Rutgers, one may question what courses of action the university adopted in order to cope with this contemptuous climate. Well, it appears as though Rutgers University failed to execute policies that would sufficiently alleviate the injustices homosexuals experienced as a result of their sexuality. The lack of efficient university policies to conquer harassment of homosexuals is evident in the statistics; of the sixty seven students who stated they were harassed because of their sexuality, eighty eight percent did not inform the university of the injustices directed towards them for they strongly felt the university would react passively, failing to address the issue (Cavin, p. 5).

Such students had every reason to believe that the university would not respond positively to their plea for aid, for the university rarely provided persecuted homosexuals with any support. For example, after the lesbian student was threatened by her peer with a handgun, she immediately contacted campus police. Unfortunately, campus police ultimately expressed that the perpetrator would not have committed such as act if the lesbian student had not done anything to deserve it. Moreover, the perpetrator was not charged with any crime and the university permitted him to continue his education, without penalty . Moreover, another student expressed that when she was harassed by her departmental chair due to her lesbianism, the university “did a real number in order to wash their hands off and not investigate the matter . . . they are very likely to never act to solve my being harassed (Cavin, p. 24).” Ultimately, the university and its staff, if it did not serve as the perpetrator, or source of persecution, it generally looked the other way in the face of the oppression of homosexuals. Sometimes, however, failing to take any action to correct inequities and doing nothing at all is equally as abominable as committing the acts of injustice.

The Rutgers Sexual Orientation Survey, devised by the head of the Women’s Studies Program, Susan Cavin, further exposed the inadequacy on the part of the university to alleviate unfair treatment directed towards homosexual students; such exposure served as a catalyst for the implementation of more stringent university policies regarding the oppressive treatment directed towards homosexual individuals. On February 3, 1988, in conjunction with the recommendations provided by Susan Cavin’s survey, a Select Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns assembled and presented specific courses of action the university could take to seriously mitigate the injustices directed towards homosexuals on campus.

The first objective of the Select Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns was to establish an Office for Gay and Lesbian Concerns with a minimum of a one full-time staff member, which would monitor the implementation of policies aimed at creating an environment free of fear, violence, or harassment. Ultimately, this office would “serve as a gentle reminder of what needs to be done, what hasn’t been done, and what should be done (Anderson, p. 9).”

After an Office of Gay and Lesbian Concerns was established, the university wished to provide additional education regarding gay and lesbian individuals. Specifically, the university sought to invest more resources into a new curriculum, which included the study of homosexual individuals. The university believed that the creation of official curriculums, which focused on gay and lesbian issues, would convince individuals of the significance of academics directed towards homosexuality.

Thirdly, the committee wished to develop anti-homophobic activities that would familiarize students with homosexuality, foster cooperation between heterosexual and homosexual students and thus, reduce negative perceptions of homosexual individuals. Finally, although it acknowledged that it would be a long term process, the university was determined to create a safe space for homosexual students, in which they would be free to demonstrate their sexuality without penalty and access benefits and services, which they were frequently denied (Anderson, p. 10).

It has been nearly twenty one years since the Rutgers Select Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns assembled to devise a plan of action that would combat the threatening environment that surrounded homosexual students in the 1970’s and 1980’s. I feel it is now an appropriate time to evaluate the success of the Select Committee’s objectives. The Office for Gay and Lesbian Concerns, which was created quickly after the Select Committee’s recommendation, continues to exist to this day on 3 Bartlett Street; in 1995 the university modified the title of this office, calling it the Office of Social Justice Education and LGBT Communities [SJE]. The primary mission of SJE is to “consolidate the university’s efforts to enhance the quality of queer students’ campus life for this community (Office, 1).” Ultimately, the SJE is carrying out the suggestions the Select Committee made in 1988: it reviews the steps the university has already taken to create a comfortable environment for queer students, evaluates the effectiveness of these steps, ponders any alternative courses of action the university can potentially take, and coordinates the optimal means by which the university can execute novel courses of action. Ultimately, the SJE serves as a watchful overseer of the other objectives the Select Committee of 1987 desired to see accomplished in future generations.

Hence, the SJE is intended to monitor that the university provides sufficient education regarding queer individuals. For example, the university wished to devise a curriculum that would promote the study of queer individuals, which would encourage people to adopt positive attitudes towards those of queer identity. Thus far, the university has succeeded at making information regarding queer individuals available. Specifically, the university provides a class that emphasizes the history of gay, lesbian, transgender, and bisexual peoples. Moreover, according to Cheryl Clarke, the university also offers voluntary conferences, which are complete with discourse pertaining to queer concerns.

Furthermore, the SJE also serves as a guide to stimulate an environment in which queer students feel secure and welcome. In order to accomplish this, the SJE ultimately encourages the university to provide ample activities that demonstrate acclaim for queer individuals. For example, the university currently offers a new student orientation directed specifically towards students who identify as queer, which is an attempt to embrace new homosexual students and make them feel that they have entered a safe and accepting environment. Moreover, the university provides a rainbow graduation, which is a way in which the university celebrates the achievements of LGBT students. Furthermore, the month of April, or GAYpril, as Cheryl Clarke calls it, is dedicated to community knowledge of AIDS awareness (Clarke, Cheryl). In addition to activities that intend to furnish a comfortable climate for queer individuals, the university also administers support services such as advising, counseling, and referrals to any resources on campus, which also assist queer students.

Despite the strides Rutgers University has made in its progression towards a campus that welcomes further integration of queers, there area specific personnel that are associated with the university that do not adhere to the antidiscrimination tactics at Rutgers. For example, The Reserve Officer Training Corps [ROTC], located on College Avenue, is compliant to the United States Department of Defense policy, known as “don’t ask, don’t tell.” This policy ultimately grants the ROTC the authority to reject any students of homosexual orientation. Although the ROTC argues that its practices are federal affairs, instead of university concerns, the university community begs to differ. An ROTC student expresses,

“The issue is of academic freedom. An ROTC student who comes under suspicion of being gay could be tossed out. A straight student might be afraid to go to lecture by a visiting gay professor or associate with gay students. Even a straight student cannot function freely (Reilly, p. 1).”

Moreover, the New Jersey law that prohibits state employees from claiming their same sex partners as dependents on their health insurance has also undermined the advances the university has made towards a community that is cordial and sympathetic towards queers. In 1997, Professor Louie Crew, who teaches at the Newark campus, along with Professor William Mayo of the Piscataway campus, were two of five homosexual faculty whose partners were denied health insurance coverage (Schwaneberg, p. 1). Although the rejection of insurance benefits to same sex partners was not under the discretion of the university, it still had the potential to alter the anti-discriminatory image Rutgers was eager to construct. Hence, it is clear from the aforementioned cases of discrimination [against ROTC students and faculty] that regardless of the immense effort the university invests in creating a welcoming environment, there will always exist some degree of disfavor for individuals of queer identity.

In conclusion, the campus climate at Rutgers University during the 1970’s and 1980’s was infused with a large degree of homophobia. As a result, queer individuals were forced to either conceal their identities, or expose their queer identities with the risk of undergoing immense persecution. In 1988, Susan Cavin devised a Rutgers Sexual Orientation survey, which served as a means by which such homophobia could be exposed to the Rutgers community. This survey prompted the university to formulate the Select Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns, which was an active and relatively successful attempt at alleviating the injustices queer individuals experienced as a consequence of their identities. Today, nearly twenty one years after the Select Committee convened, the Rutgers community possesses an increasingly welcoming demeanor, which embraces identity diversity. Unfortunately, federal policies such as “don’t ask, don’t tell” and the national law that prohibits partners from same sex unions from receiving health insurance benefits is frustrating the decades of progress Rutgers University has made towards the establishment of a congenial environment that embraces queerness.

Tracing Queer Origins