Difference between revisions of "Cathedral of St. Paul"

m |

|||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The fist event took place when the magnificent cathedral was merely a religious man’s dream. Bishop John Ireland—who secured the building’s site, chose Emmanual Masqueray as its architect, and saw to its financing—was an Irish-born civic leader. His attachment to the nation of Ireland led to a curious friendship with none other than the most famous gay Irishman in the world—Oscar Wilde. For, and during a visit to the Twin Cities in March of 1882,<small>(1)</small>the future Archbishop stood onstage with the aesthete at a St. Patrick’s day rally—Wilde even gave Bishop Ireland a signed autograph.<small>(2)</small> | The fist event took place when the magnificent cathedral was merely a religious man’s dream. Bishop John Ireland—who secured the building’s site, chose Emmanual Masqueray as its architect, and saw to its financing—was an Irish-born civic leader. His attachment to the nation of Ireland led to a curious friendship with none other than the most famous gay Irishman in the world—Oscar Wilde. For, and during a visit to the Twin Cities in March of 1882,<small>(1)</small>the future Archbishop stood onstage with the aesthete at a St. Patrick’s day rally—Wilde even gave Bishop Ireland a signed autograph.<small>(2)</small> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| {{prettytable}} | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

! | ! | ||

| Line 17: | Line 15: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| The second event took place long after the Cathedral of St. Paul moved from its former location at Sixth and St. Peter Streets to its majestic home atop Cathedral Hill. In 1977, Archbishop John R. Roach received the Brotherhood Award at a dinner hosted by the National Conference of Christians and Jews. | | The second event took place long after the Cathedral of St. Paul moved from its former location at Sixth and St. Peter Streets to its majestic home atop Cathedral Hill. In 1977, Archbishop John R. Roach received the Brotherhood Award at a dinner hosted by the National Conference of Christians and Jews. | ||

| + | |||

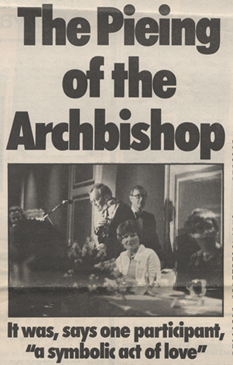

22 year-old Patrick Swartz, a member of the radical Target City Coalition, tossed a chocolate cream pie in the direction of the archbishop’s face.<small>(3)</small> Schwartz’s rationale? The archbishop sent a lobbyist to the State Capitol to vote against an ill-fated gay rights bill. | 22 year-old Patrick Swartz, a member of the radical Target City Coalition, tossed a chocolate cream pie in the direction of the archbishop’s face.<small>(3)</small> Schwartz’s rationale? The archbishop sent a lobbyist to the State Capitol to vote against an ill-fated gay rights bill. | ||

| + | |||

Gay and straight citizens alike responded with mixed reactions to the shocking act, which received statewide newspaper attention. Schwartz and the Archbishop later met, shook hands, and both apologized for inflicting harm on the other. While the Cathedral itself is not a particular site of LGBT interest, it represents two Catholic leaders who had significant interactions with queer men. | Gay and straight citizens alike responded with mixed reactions to the shocking act, which received statewide newspaper attention. Schwartz and the Archbishop later met, shook hands, and both apologized for inflicting harm on the other. While the Cathedral itself is not a particular site of LGBT interest, it represents two Catholic leaders who had significant interactions with queer men. | ||

| + | |||

| [[Image:Svc_archbishopPieing.jpg]]<div style="text-align: center;"> | | [[Image:Svc_archbishopPieing.jpg]]<div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

Revision as of 22:36, 27 February 2010

Selby Avenue at John Ireland Boulevard, St. Paul

Hopefully not a place of sexual activity, the seat of the archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis is an important institution and historical site for St. Paul’s queer community. Two particular events—separated by almost a century—are largely responsible for the building’s placement on this list.

The fist event took place when the magnificent cathedral was merely a religious man’s dream. Bishop John Ireland—who secured the building’s site, chose Emmanual Masqueray as its architect, and saw to its financing—was an Irish-born civic leader. His attachment to the nation of Ireland led to a curious friendship with none other than the most famous gay Irishman in the world—Oscar Wilde. For, and during a visit to the Twin Cities in March of 1882,(1)the future Archbishop stood onstage with the aesthete at a St. Patrick’s day rally—Wilde even gave Bishop Ireland a signed autograph.(2)

| The second event took place long after the Cathedral of St. Paul moved from its former location at Sixth and St. Peter Streets to its majestic home atop Cathedral Hill. In 1977, Archbishop John R. Roach received the Brotherhood Award at a dinner hosted by the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

22 year-old Patrick Swartz, a member of the radical Target City Coalition, tossed a chocolate cream pie in the direction of the archbishop’s face.(3) Schwartz’s rationale? The archbishop sent a lobbyist to the State Capitol to vote against an ill-fated gay rights bill.

Gay and straight citizens alike responded with mixed reactions to the shocking act, which received statewide newspaper attention. Schwartz and the Archbishop later met, shook hands, and both apologized for inflicting harm on the other. While the Cathedral itself is not a particular site of LGBT interest, it represents two Catholic leaders who had significant interactions with queer men.

|

Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies |

(1)Flanagan, John T. “Oscar Wilde’s Twin City Appearances,” 1936. (2)Ast, Emilie. “Oscar Wilde Shared Stage with Bishop Ireland.” The Catholic Spirit, June 22, 2000. Page 48a. (3)“The Pieing of the Archbishop.” Metropolis: 5/24/1977

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)