Difference between revisions of "Twin Cities Pride Festival"

(New page: Image:Svc_braggaboutit_76.jpg <div style="text-align: center;"> <small>'''1976 Twin Cities Pride Poster, 1976. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies.'''</s...) |

m (Protected "Twin Cities Pride Festival" [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | <div style="text-align: center;"> | |

| − | + | '''[[Loring Park]], Minneapolis, MN''' | |

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[Image:Svc_braggaboutit_76.jpg]] <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | <small>'''1976 Twin Cities Pride Poster, 1976. Courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | | The most significant annual event in Minnesota’s LGBT history began in 1972 as a picnic in Loring Park’s northeast corner. Organized by [[F.R.E.E.]] at the University of Minnesota and members of [[Gay House]], the state’s first Pride celebration was a simple social gathering with less than 100 attendees. These young people gathered to celebrate the Stonewall Riots in New York City. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “Stonewall” took place in 1969, and it was the first publicized queer uprising in contemporary history. Twin Cities Pride grew slowly during the 1970s and only changed to accommodate local social and political organizations. Directors of these groups shared a single megaphone to give their annual progress reports, often taking several hours.<small>(1)</small> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the early 1980s, a new Pride Committee took control from the dysfunctional (if pioneering and well-intentioned) Pride committee of the past decade. The new group introduced the annual Block Party (then on Hennepin Avenue), secured permits for use of [[Loring Park]] and Hennepin Avenue, and published “Pride Guides” that included articles written by community members.<small>(2)</small> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | The event became a true festival around 1990, following the trend of other Pride celebrations. With attendance numbering in the thousands and scores of vendors, the Pride Committee requested vendor applications and began to arrange booths around Loring Lake. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Music venues also expanded and required multiple stages by the mid-90s. The Pride Committee started accepting corporate sponsorship money in the late 1990s to accommodate this exponentially-increasing patronage. As 2000 came and went, attendance numbered more than 100,000 people.<small>(3)</small> | ||

| + | | <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | [[Image:SVC_Gay_Pride_'79.jpg]] | ||

| + | </div> <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | '<small>''The Twin Cities Pride Committee Logo, c.1977. The image is a reference to the once-popular act of pieing (see:the [[Cathedral of St. Paul]]) Courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small></div> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | The 2000s were a decade of expansion, outreach, and professional development. Vendors stalls and non-profit booths—numbering in the hundreds—spanned out from the lake along park paths. The Pride Committee expanded events throughout the calendar year and introduced a new “family area” and a space for commitment ceremonies.<small>(4)</small> In its 38th year, Pride expects an attendance of 400,000—more than the population of the City of Minneapolis, making it the third-largest pride event in the nation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | == Pride Guides == | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <gallery> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide1.jpg|<small>'''The first Twin Cities Pride Guide, 1973. The single sheet of paper is designed to be folded and thrown in the event of a police raid.'''</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide2.jpg|'''<small>1974 Pride Guide. About 350 attend the event, which includes the first transgender speaker</small>''' | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide3.jpg|<small>'''1975 Pride Guide. Ruth Sherman acts as Grand Marshal of the [[Twin Cities Pride Parade]]. Approximately 500 attend.'''</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide4.jpg|'''<small>1977 Pride Guide. The first booths and vendors set up in [[Loring Park]], and the parade changes to Hennepin Avenue.</small>''' | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide5.jpg|<small>1978 Pride Guide from the Minneapolis protest. Bisexual activists wanted inclusion but were ignored by the committee.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide6.jpg|<small>1978 Pride Guide from the St. Paul picnic, which suffered from the recent repeal of equal rights and terrible weather.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide7.jpg|<small>1979 Pride Guide. The rally, picnic, and parade become recognizable as a cohesive festival.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide8.jpg|<small>1980 Pride Guide. More than 2,000 attend.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide9.jpg|<small>1981 Pride Guide. "Fresh Fruit" airs the first public broadcast of Pride events through KFAI Radio.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide10.jpg|<small>1982 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee removes "Lesbian" from its title, resulting in a [[Loring Park]] "Gay Pride" and a [[Powderhorn Park]] "Lesbian Pride."</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide11.jpg|<small>1983 Pride Guide. The City of Minneapolis permits street closures for the parade and block party for the first time.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide12.jpg|<small>1984 Pride Guide. More than 5,000 attend the festival, and a history exhibit in St. Paul's landmark center commemorates the 15th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide13.jpg|<small>1985 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee attempts to gate the festival and charge admission. Amid the AIDS crisis, the community rejected this decision. Attendance was low.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide14.jpg|<small>1986 Pride Guide. The [[Minnesota AIDS Project (MAP)]] organizes the event after the Pride Committee collapses financially.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide15.jpg|<small>1987 Pride Guide. The new Pride Committee hosts the event at [[Powderhorn Park]], and extends the parade route to 2 1/2 miles along 32nd Street.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide16.jpg|<small>1988 Pride Guide. 7,500 attend the festival, and the Pride Committee shortens the parade route.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide17.jpg|<small>1989 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee breaks from the G.L.C.A.C. (later [[OutFront Minnesota]]) and becomes its own nonprofit group. Five Grand Marshals are selected to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide90.jpg|<small>1990 Pride Guide. The [[Twin Cities Pride Festival]] expands to a week-long event, and over 15,000 attend.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide19.jpg|<small>1991 Pride Guide. Over 25,000 attend the popular Pride Weekend events, and the Committee begins selecting festival vendors from a pool of applications.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide20.jpg|<small>1992 Pride Guide. More than 100 vendors set up in [[Loring Park]], the History Pavilion debuts, and 50,000 enjoy the warm weather during Pride Weekend.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide21.jpg|<small>1993 Pride Guide. Ashley Rukes coordinates more than 100 entries in the [[Twin Cities Pride Parade]], 75,000 take part in "A Family of Pride"</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide22.jpg|<small>1994 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee builds a second performance stage in [[Loring Park]], and St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman refuses to sign a proclamation of GLBT Pride Month.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide95.jpg|<small>1995 Pride Guide. Despite rainy weather, 100,000 take part in Pride Events. Issues with [[Lavender Magazine]] result in a "Guideless Pride."</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide24.jpg|<small>1996 Pride Guide. [[District 202]] leads the [[Twin Cities Pride Parade]], and the ''Minneapolis Star-Tribune'' prints a 100-page Pride Guide. Coporations begin sponsoring the event.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide25.jpg|<small>1997 Pride Guide. The Twin Cities Pride Committee decides to move the festival to Nicollet Island while [[Loring Park]]is under reconstruction, and [[Capital City Pride]] is established.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide26.jpg|<small>1998 Pride Guide. 200,000 attend the festival in a reconstructed [[Loring Park]], despite rumors that the festival was on the verge of financial ruin.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide27.jpg|<small>1999 Pride Guide. 108 Rainbow banners are installed along Hennepin Avenue to commemorate the 30th Anniversary of the Stonewall Riots and the founding of [F.R.E.E.]. </small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide28.jpg|<small>2000 Pride Guide. 250,000 attend Pride events and the Pride Committee renames the parade in honor of Ashley Rukes, to commemorate the director's unexpected passing.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide29.jpg|<small>2001 Pride Guide. 350,000 attend Pride weekend, and Beverly Little thunder becomes the first female Native American Grand Marshal.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide30.jpg|<small>2002 Pride Guide. Mayor Sharon Sayles Belton is Grand Marshal for the 30th anniversary of Twin Cities Pride.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide31.jpg|<small>2003 Pride Guide. 400,000 attend despite mounting concerns related to corporate fundraising and sexually explicit themes.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide32.jpg|<small>2004 Pride Guide. Twin Cities Pride becomes the third-largest Pride event in the nation. Dr. Linnea Stenson, an activist and scholar promoting GLBT Studies, is Grand Marshal.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide33.jpg|<small>2005 Pride Guide. Anguksuar (Richard LaFortune), a two-spirited citizen of the Yuupit Nation and HIV/AIDS activist, is Grand Marshal. Over 400 vendors and exhibitors sign up for the festival.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide34.jpg|<small>2006 Pride Guide. A fourth performance stage is introduced, and 435,000 attend the weekend events. Ann Bancroft, the first woman to finish an Antarctic expedition, is Grand Marshal.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide35.jpg|<small>2007 Pride Guide.Rainbow Families Partners with Twin Cities Pride to host the festival. A pocket-sized Pride Guide debuts.</small> | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide36.jpg|2008 Pride Guide. | ||

| + | Image:Svc_pguide37.jpg|2009 Pride Guide. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| − | + | <small>(1)</small> Tretter, Jean-Nickolaus, Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. January, 2009. | |

| + | |||

| + | <small>(2)</small> Curnoyer, Nancy "Nan." Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. February, 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>(3)</small> Twin Cities Pride Guides, 1991-1998. From the "Twin Cities Pride Collection." Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection ing GLBT Studies: University of Minnesota Libraries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>(4)</small> Nienaber, William (Bill). Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. April, 2009. | ||

Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:21, 1 May 2010

Loring Park, Minneapolis, MN

1976 Twin Cities Pride Poster, 1976. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

The most significant annual event in Minnesota’s LGBT history began in 1972 as a picnic in Loring Park’s northeast corner. Organized by F.R.E.E. at the University of Minnesota and members of Gay House, the state’s first Pride celebration was a simple social gathering with less than 100 attendees. These young people gathered to celebrate the Stonewall Riots in New York City.

|

| The event became a true festival around 1990, following the trend of other Pride celebrations. With attendance numbering in the thousands and scores of vendors, the Pride Committee requested vendor applications and began to arrange booths around Loring Lake.

Music venues also expanded and required multiple stages by the mid-90s. The Pride Committee started accepting corporate sponsorship money in the late 1990s to accommodate this exponentially-increasing patronage. As 2000 came and went, attendance numbered more than 100,000 people.(3) |

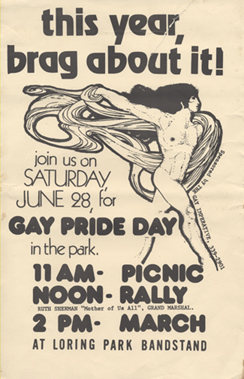

'The Twin Cities Pride Committee Logo, c.1977. The image is a reference to the once-popular act of pieing (see:the Cathedral of St. Paul) Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection.'

|

The 2000s were a decade of expansion, outreach, and professional development. Vendors stalls and non-profit booths—numbering in the hundreds—spanned out from the lake along park paths. The Pride Committee expanded events throughout the calendar year and introduced a new “family area” and a space for commitment ceremonies.(4) In its 38th year, Pride expects an attendance of 400,000—more than the population of the City of Minneapolis, making it the third-largest pride event in the nation.

Pride Guides

1975 Pride Guide. Ruth Sherman acts as Grand Marshal of the Twin Cities Pride Parade. Approximately 500 attend.

1977 Pride Guide. The first booths and vendors set up in Loring Park, and the parade changes to Hennepin Avenue.

1982 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee removes "Lesbian" from its title, resulting in a Loring Park "Gay Pride" and a Powderhorn Park "Lesbian Pride."

1986 Pride Guide. The Minnesota AIDS Project (MAP) organizes the event after the Pride Committee collapses financially.

1987 Pride Guide. The new Pride Committee hosts the event at Powderhorn Park, and extends the parade route to 2 1/2 miles along 32nd Street.

1989 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee breaks from the G.L.C.A.C. (later OutFront Minnesota) and becomes its own nonprofit group. Five Grand Marshals are selected to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

1990 Pride Guide. The Twin Cities Pride Festival expands to a week-long event, and over 15,000 attend.

1992 Pride Guide. More than 100 vendors set up in Loring Park, the History Pavilion debuts, and 50,000 enjoy the warm weather during Pride Weekend.

1993 Pride Guide. Ashley Rukes coordinates more than 100 entries in the Twin Cities Pride Parade, 75,000 take part in "A Family of Pride"

1994 Pride Guide. The Pride Committee builds a second performance stage in Loring Park, and St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman refuses to sign a proclamation of GLBT Pride Month.

1995 Pride Guide. Despite rainy weather, 100,000 take part in Pride Events. Issues with Lavender Magazine result in a "Guideless Pride."

1996 Pride Guide. District 202 leads the Twin Cities Pride Parade, and the Minneapolis Star-Tribune prints a 100-page Pride Guide. Coporations begin sponsoring the event.

1997 Pride Guide. The Twin Cities Pride Committee decides to move the festival to Nicollet Island while Loring Parkis under reconstruction, and Capital City Pride is established.

1998 Pride Guide. 200,000 attend the festival in a reconstructed Loring Park, despite rumors that the festival was on the verge of financial ruin.

(1) Tretter, Jean-Nickolaus, Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. January, 2009.

(2) Curnoyer, Nancy "Nan." Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. February, 2009.

(3) Twin Cities Pride Guides, 1991-1998. From the "Twin Cities Pride Collection." Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection ing GLBT Studies: University of Minnesota Libraries.

(4) Nienaber, William (Bill). Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. April, 2009.

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)