Difference between revisions of "Reading Material"

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

:My dear Leo: | :My dear Leo: | ||

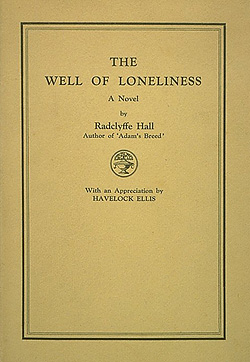

:Yes – I have read “Well of Loneliness” and I am willing to testify that if Miss Radcliffe [sic] Hall can love like she can write she is certainly not sex starved. From beginning to end the book is a rhythmic pleasure, and approaching it as I did from a wholesomely normal and purely impersonal viewpoint I probably appreciated it even more than you did. <div style="text-align: right; direction: ltr; margin-left: 1em;">Yours as ever / Merely Merle</div> | :Yes – I have read “Well of Loneliness” and I am willing to testify that if Miss Radcliffe [sic] Hall can love like she can write she is certainly not sex starved. From beginning to end the book is a rhythmic pleasure, and approaching it as I did from a wholesomely normal and purely impersonal viewpoint I probably appreciated it even more than you did. <div style="text-align: right; direction: ltr; margin-left: 1em;">Yours as ever / Merely Merle</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Macbain was not alone among straight readers who enjoyed Hall's ground-breaking lesbian novel. The Well of Loneliness incited an obscenity trial in the United Kingdom and was subsequently banned in Britain. The publisher of the first American edition (New York: Covici Friede, 1928) successfully fought an obscenity charge and the book sold over 100,000 copies in the U.S. in its first year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

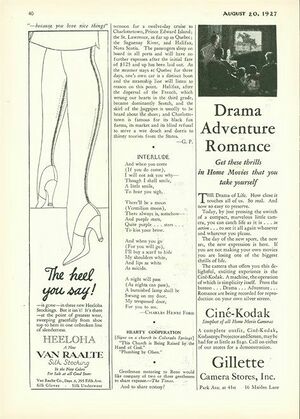

| + | Adams and Macbain also shared a taste for a certain kind of "sophisticated sentimentality" in poetry and shared their findings through their correspondence. In the following passage, Macbain responds to a selection forwarded by Adams early in 1932, including a clipping from an old edition of ''The New Yorker'': | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Ford_Interlude_New_Yorker.jpg|thumb|left|Charles Henri Ford, "Interlude," ''The New Yorker,'' August 20, 1927, 40.]] | ||

| + | :Dear Leo: | ||

| + | :Your poetry, in the selection of which you show a sure instinct for the exact type of sophisticated sentimentality that I permit myself to approve of, is well received. The one with the "vermillion moon" and lips "as white as suicide" is of the stuff that poetry is made of though the author Charles Henri Ford is unknown to me. There seems now to be a small group of nascent versifiers preparing to take the place of the "New Voices" which somehow never fulfilled their promise.<ref>Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, February 1932 (undated).</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The poem Macbain refers to is Charles Henri Ford's "Interlude." It is not surprising that Adams, as an avid ''New Yorker'' reader, would have stumbled upon Ford's poem. What is remarkable (although probably more so as a happy accident than as a bit of conscious foresight) is that Adams should single out the first published piece by the man who would go on to co-author, with Parker Tyler, ''The Young and Evil'', a racy roman-a-clef about their lives amidst the gay subculture of Greenwich Village in New York City.<ref>Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, ''The Young and Evil'' (Paris: Obelisk Press, 1933).</ref> | ||

Revision as of 11:21, 11 May 2011

"[Lady Chatterley's Lover] is, to say the least, a powerful aphrodisiac and I have it on the personal testimony of one who lisps that its descriptions of the normal sex act could do more than the arts of psychoanalysis to make an erring homo renounce his red tie and begin annoying women."--Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, October 12, 1929.[1]

In the early-to-mid twentieth century, before the existence of an active gay press or bookstores, gay men and lesbians necessarily relied on word of mouth and the sharing of books and periodicals among circles of friends for gay-themed reading material. Leo Adams's letters are a rich source of material about what he and his friends were reading from the late 1920s to the years immediately following World War II--a period that witnessed significant changes in both the quantity and the style of popular gay and lesbian literature. Adams's most remarkable correspondent in this regard is Merle Macbain, editor of The Greater Chicago Magazine in the late 1929s, and later a Commander in the United States Navy who served as a technical adviser in the 1955 film Mister Roberts. Perhaps most remarkable about their literary relationship is that Macbain, a straight, married man who boasts of having slept "with at least 300 women,"[2] takes such an active interest in Leo Adams's gay reading list. In many ways, Macbain was a more progressive--more queer, even--reader than Adams, whose taste in imaginative literature ran towards The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post. As the passage quoted at the top of this page suggests, Macbain was familiar with the language and codes of the emerging queer subculture of the late 1920s,[3] also suggesting that the boarder between gay subculture and mainstream popular culture was already becoming porous.

Adams did read Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness and recommended it to Macbain. That letter is not among Adams's papers, but Macbain's, with his critical commentary, is:

- My dear Leo:

- Yes – I have read “Well of Loneliness” and I am willing to testify that if Miss Radcliffe [sic] Hall can love like she can write she is certainly not sex starved. From beginning to end the book is a rhythmic pleasure, and approaching it as I did from a wholesomely normal and purely impersonal viewpoint I probably appreciated it even more than you did. Yours as ever / Merely Merle

Macbain was not alone among straight readers who enjoyed Hall's ground-breaking lesbian novel. The Well of Loneliness incited an obscenity trial in the United Kingdom and was subsequently banned in Britain. The publisher of the first American edition (New York: Covici Friede, 1928) successfully fought an obscenity charge and the book sold over 100,000 copies in the U.S. in its first year.

Adams and Macbain also shared a taste for a certain kind of "sophisticated sentimentality" in poetry and shared their findings through their correspondence. In the following passage, Macbain responds to a selection forwarded by Adams early in 1932, including a clipping from an old edition of The New Yorker:

- Dear Leo:

- Your poetry, in the selection of which you show a sure instinct for the exact type of sophisticated sentimentality that I permit myself to approve of, is well received. The one with the "vermillion moon" and lips "as white as suicide" is of the stuff that poetry is made of though the author Charles Henri Ford is unknown to me. There seems now to be a small group of nascent versifiers preparing to take the place of the "New Voices" which somehow never fulfilled their promise.[4]

The poem Macbain refers to is Charles Henri Ford's "Interlude." It is not surprising that Adams, as an avid New Yorker reader, would have stumbled upon Ford's poem. What is remarkable (although probably more so as a happy accident than as a bit of conscious foresight) is that Adams should single out the first published piece by the man who would go on to co-author, with Parker Tyler, The Young and Evil, a racy roman-a-clef about their lives amidst the gay subculture of Greenwich Village in New York City.[5]

Notes

- ↑ Leo Adams Papers, New York Public Library

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, January 1932. Leo Adams Papers, New York Public Library (hereafter cited by name and date only).

- ↑ The red necktie had, by the 1920s, become a recognized signifier of homosexual identity. See, among others, George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 522; and Shaun Cole, "Macho Man: Clones and the Development of a Masculine Stereotype," Fashion Theory 4 (2000): 126

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, February 1932 (undated).

- ↑ Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, The Young and Evil (Paris: Obelisk Press, 1933).

Back to Leo Adams: A Gay Life in Letters, 1928–1952 <comments />