Difference between revisions of "Faith S. Holsaert: "Chosen Girl," 2003"

| (13 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | Reprinted with the permission of Faith S. Holsaert. Copyright (c) 2003 by Faith S. Holsaert. For reproduction rights contact author at: writerwk1@mac.com | |

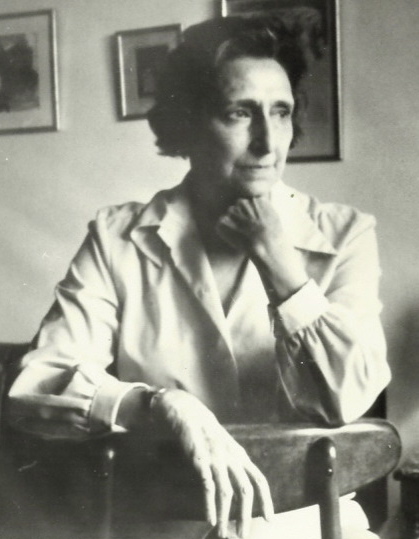

| − | + | [[Image:Shai,Faith,Charity.jpg|650px]] | |

| + | L to R: Shai and Faith Holsaert, Charity Bailey. All photos courtesy of Faith Holsaert. | ||

| + | __noTOC__ | ||

==Introduction by Jonathan Ned Katz== | ==Introduction by Jonathan Ned Katz== | ||

| − | This long short story (80,000 words), set in the 1950s, in progressive, literary Greenwich Village, subtly evokes the loving, conflicted, and ultimately thwarted intimacy between two women, one white and the other African American, as | + | This long short story (80,000 words), set in the 1950s, in progressive, literary {{Semplace|Greenwich Village}}, subtly evokes the loving, conflicted, and ultimately thwarted intimacy between two women, one white and the other African American, as seen through the eyes of the white woman's smart, observant daughter. The three live together. |

| Line 13: | Line 15: | ||

| − | The writer, Faith Holsaert, was raised on Jane Street, in the Village, in a two-mother family by | + | The writer, Faith Holsaert, was raised with her sister Shai on Jane Street, in the Village, in a two-mother family by their Jewish mother by birth, Eunice Holsaert, and Charity Bailey, their mother by affection. Bailey was the music teacher at the Little Red School House where Faith was enrolled, and Bailey later hosted a children's TV show in New York City. |

| − | I also attended "Little Red," as we called this "progressive school," and fondly remember "Charity" (we called most of our teachers by their first names) visiting my family, discussing the history of Black spirituals with my father who knew much African American history and culture. I also recall Charity radiating concern for and kindness toward young people, a kindness to which I especially responded. I also remember coming home from | + | [[Image:Eunice Holsaert.jpg|right|frame|425px|Eunice Holsaert.]] |

| − | + | ||

| + | I also attended "Little Red," as we called this private "progressive school," and fondly remember gentle but firm "Charity" (we called most of our teachers by their first names). I recall her visiting my family, and discussing the history of Black spirituals with my father who knew much about African American history and culture. I also recall Charity radiating concern for and kindness toward young people, a kindness to which I especially responded. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | I also remember coming home from one 1950s visit to Charity Bailey's and Eunice Holsaert's apartment and my mother asking, circumspectly, without explanation, how many beds there were. Annoyed at her prying suspicion, and her asking me to inform on a beloved teacher, I think I said: "Two." I understood vaguely, I think, that my mother was inquiring whether the two women slept together, and that, if true, this was bad. Like much fiction, "Chosen Girl" seemingly contains more than a few autobiographical elements. | ||

| + | |||

Faith Holsaert has published numbers of stories and memoirs, mostly in small literary journals. “Chosen Girl” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. “Creekers” (fiction) won first place in the Kentucky Writers Coalition Competition, in 2004. That year, “Freedom Rider, circa 1993” (fiction) won third place in the Fugue Annual Contest in Prose. “History Dancing,” a memoir, appeared in the autumn of 2006, in a collection published by University of Iowa Press. | Faith Holsaert has published numbers of stories and memoirs, mostly in small literary journals. “Chosen Girl” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. “Creekers” (fiction) won first place in the Kentucky Writers Coalition Competition, in 2004. That year, “Freedom Rider, circa 1993” (fiction) won third place in the Fugue Annual Contest in Prose. “History Dancing,” a memoir, appeared in the autumn of 2006, in a collection published by University of Iowa Press. | ||

| − | I highly recommend this sensitive, wonderfully written art about history | + | I highly recommend this sensitive, wonderfully written art about history. I'm also pleased to honor the memory of Charity Bailey, who, I like to think, had she lived into the present, could have understood our need to look back and specify what we see. "Chosen Girl" is also available in paginated form (48 pages) on the 2004 edition of the web publication ''The King's English'' (pages 7-55).[http://home.comcast.net/~wapshot1/spr09/TKE.NF2004.pdf] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Easter coats.jpg|frame|left|Easter coats: Faith, Eunice, Shai Holsaert. Faith says: "Charity sewed my coat."]] | ||

=="Chosen Girl" by Faith S. Holsaert== | =="Chosen Girl" by Faith S. Holsaert== | ||

| − | I. | + | =I.= |

In the beginning were my parents, shoulder to shoulder, the | In the beginning were my parents, shoulder to shoulder, the | ||

baby floating within their massed outline. | baby floating within their massed outline. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

I sat close, in either lap, during their disputes. | I sat close, in either lap, during their disputes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

My father said, "Oliver Twist. It's a wretched book, Deirdre. | My father said, "Oliver Twist. It's a wretched book, Deirdre. | ||

You like it because you read it as a child." | You like it because you read it as a child." | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

"I like it because it's about people. Not like your Eliot, who | "I like it because it's about people. Not like your Eliot, who | ||

writes about things." | writes about things." | ||

| Line 39: | Line 55: | ||

"Deirdre, Fagan's a sentimental abomination." | "Deirdre, Fagan's a sentimental abomination." | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

She held me tight against her bosom, and I learned how her | She held me tight against her bosom, and I learned how her | ||

muscles tightened when she clenched her teeth. “Well I love that | muscles tightened when she clenched her teeth. “Well I love that | ||

| Line 45: | Line 63: | ||

“Fagan’s an anti-Semitic stereotype,” said my WASP father. | “Fagan’s an anti-Semitic stereotype,” said my WASP father. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

She struck quickly. “Are you Virginia Woolf to my | She struck quickly. “Are you Virginia Woolf to my | ||

Leonard?” My Jewish mother. | Leonard?” My Jewish mother. | ||

| Line 74: | Line 94: | ||

| − | ▼▪▲ | + | ▼▪▲ |

| Line 121: | Line 141: | ||

| − | ▼▪▲ | + | ▼▪▲ |

| Line 144: | Line 164: | ||

“Haven't you noticed her skin?” my father asked. | “Haven't you noticed her skin?” my father asked. | ||

| + | |||

I looked at my own hand. “Look,” I thrust it at my parents. | I looked at my own hand. “Look,” I thrust it at my parents. | ||

“I'm flesh colored.” From the box of crayons. | “I'm flesh colored.” From the box of crayons. | ||

| + | |||

▼▪▲ | ▼▪▲ | ||

| + | |||

At the first PTA meeting, as a pleasantry, my parents told | At the first PTA meeting, as a pleasantry, my parents told | ||

Laurel I wanted her to come live with us. | Laurel I wanted her to come live with us. | ||

| + | |||

"Do you have a room?" she asked. | "Do you have a room?" she asked. | ||

| + | |||

When my mother told me this, I demanded, "Are we going | When my mother told me this, I demanded, "Are we going | ||

to?" | to?" | ||

| + | |||

"We'll see," she said. | "We'll see," she said. | ||

| + | |||

In a few weeks, my mother said, "This afternoon, Laurel | In a few weeks, my mother said, "This afternoon, Laurel | ||

| Line 164: | Line 191: | ||

hands. You may say either 'How do you do?' or 'Pleased to meet | hands. You may say either 'How do you do?' or 'Pleased to meet | ||

you.'" | you.'" | ||

| + | |||

“Grown-ups don’t want to shake my hand.” | “Grown-ups don’t want to shake my hand.” | ||

| + | |||

She looked me in the eye, the way cats and children hate to | She looked me in the eye, the way cats and children hate to | ||

be stared at. "You will do it." | be stared at. "You will do it." | ||

| + | |||

Laurel arrived with her sister, a fine lady in a copper and | Laurel arrived with her sister, a fine lady in a copper and | ||

black skirt that rustled. | black skirt that rustled. | ||

| + | |||

"Pinny, for the poet Pindar," Laurel said when she | "Pinny, for the poet Pindar," Laurel said when she | ||

introduced her sister. The sisters said, "No, thank you," to stingers | introduced her sister. The sisters said, "No, thank you," to stingers | ||

in long-stemmed glasses. | in long-stemmed glasses. | ||

| + | |||

"Are you going to move in?" I asked Laurel, who said, "We'll | "Are you going to move in?" I asked Laurel, who said, "We'll | ||

see." | see." | ||

| + | |||

The grown-ups looked at the extra bedroom and returned to | The grown-ups looked at the extra bedroom and returned to | ||

sit in the living room. | sit in the living room. | ||

| + | |||

"Did you like it?" I asked, but they ignored me. | "Did you like it?" I asked, but they ignored me. | ||

| + | |||

It was the end of the afternoon and I remember the three | It was the end of the afternoon and I remember the three | ||

| Line 198: | Line 233: | ||

sisters skittishly over the beak of her nose, blue-black hair falling | sisters skittishly over the beak of her nose, blue-black hair falling | ||

in one eye. | in one eye. | ||

| + | |||

"Deborah, come see," Pinny said, and rummaged in her | "Deborah, come see," Pinny said, and rummaged in her | ||

| Line 204: | Line 240: | ||

palm of her hand, Pinny held two inch-long metal dogs, one black, | palm of her hand, Pinny held two inch-long metal dogs, one black, | ||

one white. | one white. | ||

| + | |||

"What are they?" I asked. | "What are they?" I asked. | ||

| + | |||

"The Black and White Scotch Scotties," Pinny said. | "The Black and White Scotch Scotties," Pinny said. | ||

| + | |||

“What’s that?” | “What’s that?” | ||

| + | |||

“A promotion,” Laurel said. | “A promotion,” Laurel said. | ||

| + | |||

“To sell scotch. Liquor,” my mother said. | “To sell scotch. Liquor,” my mother said. | ||

| + | |||

None of it made sense, but I let it go when Pinny said, | None of it made sense, but I let it go when Pinny said, | ||

| Line 221: | Line 263: | ||

Scotties pivoted in my hand. They'd jump from my hand before | Scotties pivoted in my hand. They'd jump from my hand before | ||

they'd face one another. | they'd face one another. | ||

| + | |||

▼▪▲ | ▼▪▲ | ||

| + | |||

Sick in bed with the measles, I imagined monkeys climbing | Sick in bed with the measles, I imagined monkeys climbing | ||

| Line 229: | Line 273: | ||

they pointed their hairless fingers at me so believably, I screamed | they pointed their hairless fingers at me so believably, I screamed | ||

and interrupted my parents' and Laurel's dinner. | and interrupted my parents' and Laurel's dinner. | ||

| + | |||

My mother came to sit by my bed. | My mother came to sit by my bed. | ||

| + | |||

"Tell me a story," I begged. | "Tell me a story," I begged. | ||

| + | |||

"At the turn of the century, your grandparents' families | "At the turn of the century, your grandparents' families | ||

| Line 251: | Line 298: | ||

money by Biaggio, and he ate all those pancakes, too. That night | money by Biaggio, and he ate all those pancakes, too. That night | ||

the family ate a fat chicken purchased with his earnings." | the family ate a fat chicken purchased with his earnings." | ||

| + | |||

The monkeys had scampered off. I drank ginger ale and | The monkeys had scampered off. I drank ginger ale and | ||

drifted in and out of sleep. | drifted in and out of sleep. | ||

| + | |||

"Your grandfather bought his first book, the complete works | "Your grandfather bought his first book, the complete works | ||

of Shakespeare, from a book cart in the street. He paid twenty-five | of Shakespeare, from a book cart in the street. He paid twenty-five | ||

cents down, and ten cents a week.” | cents down, and ten cents a week.” | ||

| + | |||

The pillows were full and smooth, for my mother had | The pillows were full and smooth, for my mother had | ||

changed and plumped them. | changed and plumped them. | ||

| + | |||

"Your grandfather proposed to your grandmother." | "Your grandfather proposed to your grandmother." | ||

| + | |||

"The Dowager," I interjected. | "The Dowager," I interjected. | ||

| + | |||

"So your father calls her. Ben proposed in front of an ash | "So your father calls her. Ben proposed in front of an ash | ||

can on Delancy Street when he was twelve. He thought her the | can on Delancy Street when he was twelve. He thought her the | ||

prettiest girl in the world." | prettiest girl in the world." | ||

| + | |||

"Was he right?" | "Was he right?" | ||

| + | |||

But I didn't hear her answer. I slept. | But I didn't hear her answer. I slept. | ||

| + | |||

I awoke. She and Laurel sat in my room. | I awoke. She and Laurel sat in my room. | ||

Laurel was saying, "...papers of manumission and settled in | Laurel was saying, "...papers of manumission and settled in | ||

Rhode Island." | Rhode Island." | ||

| + | |||

"I don't think of Negroes as coming from New England," my | "I don't think of Negroes as coming from New England," my | ||

mother said. "But the way you say 'heart,' is a dead giveaway." | mother said. "But the way you say 'heart,' is a dead giveaway." | ||

| + | |||

"Just because you mispronounce 'hot.'" Laurel did not | "Just because you mispronounce 'hot.'" Laurel did not | ||

release the “R” from her throat. | release the “R” from her throat. | ||

| + | |||

"I mispronounce 'heart'?" My mother ground down on the | "I mispronounce 'heart'?" My mother ground down on the | ||

“R” with gusto. She laughed -- ha hah! | “R” with gusto. She laughed -- ha hah! | ||

| + | |||

In my fever, I drifted through cool ether, gazing down upon | In my fever, I drifted through cool ether, gazing down upon | ||

their slight figures. The cold pinched out my sight and then I | their slight figures. The cold pinched out my sight and then I | ||

blinked back into awareness. | blinked back into awareness. | ||

| + | |||

Laurel said, "Every Saturday, my father and I went to the | Laurel said, "Every Saturday, my father and I went to the | ||

| Line 297: | Line 358: | ||

embarrassed," Laurel said. "An ex-slave, rejecting the white | embarrassed," Laurel said. "An ex-slave, rejecting the white | ||

farmers' corn." | farmers' corn." | ||

| + | |||

"But that's wonderful." My mother whooped. "'For the | "But that's wonderful." My mother whooped. "'For the | ||

| Line 302: | Line 364: | ||

laughter gleamed. Laurel laughed, too. Together, they laughed and | laughter gleamed. Laurel laughed, too. Together, they laughed and | ||

wiped their eyes, unseemly as the sweat in which I lay. | wiped their eyes, unseemly as the sweat in which I lay. | ||

| + | |||

A red flannel fever engulfed me. I regained consciousness | A red flannel fever engulfed me. I regained consciousness | ||

| Line 311: | Line 374: | ||

ironed sheet. She balled up the soiled sheets and threw them in | ironed sheet. She balled up the soiled sheets and threw them in | ||

the hamper. | the hamper. | ||

| + | |||

I was too sick for family stories. She opened a chunky book | I was too sick for family stories. She opened a chunky book | ||

| Line 316: | Line 380: | ||

words. I barely heard them then, but slipped into the clean cool | words. I barely heard them then, but slipped into the clean cool | ||

words issuing from within the cloud of her cigarette smoke. | words issuing from within the cloud of her cigarette smoke. | ||

| + | |||

Sighing winds, cool earth, dripping apple trees, and the | Sighing winds, cool earth, dripping apple trees, and the | ||

repose of a child come home. How I relaxed into that home, but | repose of a child come home. How I relaxed into that home, but | ||

then Millay’s words turned on me, forcing me into the fires of Hell. | then Millay’s words turned on me, forcing me into the fires of Hell. | ||

| + | |||

I couldn’t cry to my mother: Stop. Hot. | I couldn’t cry to my mother: Stop. Hot. | ||

| + | |||

I slept. | I slept. | ||

| + | |||

The next day, I continued sick. | The next day, I continued sick. | ||

| + | |||

"When I was twelve," my mother said, "I had a massive | "When I was twelve," my mother said, "I had a massive | ||

| Line 342: | Line 411: | ||

turned right at the second corner, I saw Bud walking sedately | turned right at the second corner, I saw Bud walking sedately | ||

toward me on his dainty white feet." | toward me on his dainty white feet." | ||

| + | |||

As the afternoon progressed, my fever rose in spite of the | As the afternoon progressed, my fever rose in spite of the | ||

| Line 351: | Line 421: | ||

of course, Buddy knew.” | of course, Buddy knew.” | ||

| + | |||

The stories came one after the other, strung together by | The stories came one after the other, strung together by | ||

nothing but my mother herself, touching end to beginning to end. | nothing but my mother herself, touching end to beginning to end. | ||

| Line 364: | Line 435: | ||

eyes and tiny feet, took me to an American doctor. 'Why won't my | eyes and tiny feet, took me to an American doctor. 'Why won't my | ||

baby grow?' she demanded. | baby grow?' she demanded. | ||

| + | |||

"'She's malnourished.' said the doctor. 'Feed her, Madame. | "'She's malnourished.' said the doctor. 'Feed her, Madame. | ||

| Line 370: | Line 442: | ||

sallow child. I pulled the sheet back over my shoulder as she | sallow child. I pulled the sheet back over my shoulder as she | ||

stared into the distance. | stared into the distance. | ||

| + | |||

"Others found me attractive enough, especially as I | "Others found me attractive enough, especially as I | ||

| Line 380: | Line 453: | ||

bitterly. "He was weak in everything except his devotion to his | bitterly. "He was weak in everything except his devotion to his | ||

father.” | father.” | ||

| + | |||

I stirred to tell her I was awake. | I stirred to tell her I was awake. | ||

| + | |||

"When I was in my twenties, some of my friends called me | "When I was in my twenties, some of my friends called me | ||

| Line 388: | Line 463: | ||

Deborah, are important. If you had been a boy, I would have | Deborah, are important. If you had been a boy, I would have | ||

named you Spinoza." | named you Spinoza." | ||

| + | |||

Thank goodness I was a girl. | Thank goodness I was a girl. | ||

| + | |||

Days passed. I enjoyed the afternoon baths in dissolved | Days passed. I enjoyed the afternoon baths in dissolved | ||

| Line 398: | Line 475: | ||

was drawing to an end. The doctor had said I could go outside the | was drawing to an end. The doctor had said I could go outside the | ||

next day. | next day. | ||

| + | |||

"How come you look so angry?" I asked and pointed to the | "How come you look so angry?" I asked and pointed to the | ||

| Line 406: | Line 484: | ||

merciful middle brother. To the side was the sister, dead before my | merciful middle brother. To the side was the sister, dead before my | ||

birth, whom my mother once sadly said was a nymphomaniac. | birth, whom my mother once sadly said was a nymphomaniac. | ||

| + | |||

My mother said, "In those days, all babies were | My mother said, "In those days, all babies were | ||

| Line 413: | Line 492: | ||

goddamn picture." | goddamn picture." | ||

| + | |||

▼▪▲ | ▼▪▲ | ||

| + | |||

In the beginning, I had rested within the massed outlines of | In the beginning, I had rested within the massed outlines of | ||

my mother and father, but then Laurel came. Laurel called me, | my mother and father, but then Laurel came. Laurel called me, | ||

| Line 421: | Line 502: | ||

fever monkeys, but my father hadn’t come upstairs that night. He | fever monkeys, but my father hadn’t come upstairs that night. He | ||

stopped arguing about books with my mother. | stopped arguing about books with my mother. | ||

| + | |||

I wished he’d read to me, as he had used to, but he didn’t. | I wished he’d read to me, as he had used to, but he didn’t. | ||

| Line 434: | Line 516: | ||

Washington Square in our newly polished shoes, he took my hand | Washington Square in our newly polished shoes, he took my hand | ||

and said, "Let's go, Junior." | and said, "Let's go, Junior." | ||

| + | |||

He was gone so often, I was surprised that he was there on | He was gone so often, I was surprised that he was there on | ||

| Line 445: | Line 528: | ||

not drunk, exchanging a smile with Laurel who, like him, was | not drunk, exchanging a smile with Laurel who, like him, was | ||

sipping eggnog from a glass cup. I picked up one of the two pens. | sipping eggnog from a glass cup. I picked up one of the two pens. | ||

| + | |||

"You must never use another person's fountain pen," my | "You must never use another person's fountain pen," my | ||

| Line 455: | Line 539: | ||

glass cup in there. I sat down with the colored pencils and creamy | glass cup in there. I sat down with the colored pencils and creamy | ||

paper which my mother had given me. | paper which my mother had given me. | ||

| + | |||

In the kitchen, Laurel was talking. Among the welter of | In the kitchen, Laurel was talking. Among the welter of | ||

words, I heard damn it and like a daughter and I want. | words, I heard damn it and like a daughter and I want. | ||

| + | |||

"Don't say it," my mother said. | "Don't say it," my mother said. | ||

| + | |||

Holding up the poetry book, I asked, “Read this,” when | Holding up the poetry book, I asked, “Read this,” when | ||

| Line 468: | Line 555: | ||

photo was the same color as his uniform. "I was once married to | photo was the same color as his uniform. "I was once married to | ||

him," Laurel said. | him," Laurel said. | ||

| + | |||

My father, dressed for a party, came into the room. | My father, dressed for a party, came into the room. | ||

| + | |||

"Have you seen Deirdre?" he asked Laurel. | "Have you seen Deirdre?" he asked Laurel. | ||

| + | |||

"I'm upstairs," my mother yelled. | "I'm upstairs," my mother yelled. | ||

| + | |||

"Are you coming?" he snapped. | "Are you coming?" he snapped. | ||

| + | |||

"You know I hate cocktail parties." | "You know I hate cocktail parties." | ||

| + | |||

"Are you coming?" he repeated | "Are you coming?" he repeated | ||

| + | |||

"Jesus, no." She slammed their bedroom door. | "Jesus, no." She slammed their bedroom door. | ||

| + | |||

He put on his topcoat and left. | He put on his topcoat and left. | ||

| + | |||

▼▪▲ | ▼▪▲ | ||

| + | |||

That spring, my mother forbade me to enter their bedroom. | That spring, my mother forbade me to enter their bedroom. | ||

She said my father was sick with strep throat and that I might | She said my father was sick with strep throat and that I might | ||

| Line 495: | Line 592: | ||

into the dining room in a pale linen jacket. He had a flower in his | into the dining room in a pale linen jacket. He had a flower in his | ||

buttonhole. | buttonhole. | ||

| + | |||

"Behold, the bridegroom cometh," my mother said. | "Behold, the bridegroom cometh," my mother said. | ||

| + | |||

He looked around the room, as if he expected to see some | He looked around the room, as if he expected to see some | ||

of his cocktail friends in the corner beside the cabinet. "I'm going | of his cocktail friends in the corner beside the cabinet. "I'm going | ||

out," he said. | out," he said. | ||

| + | |||

My mother called me to her. "Your father and I are | My mother called me to her. "Your father and I are | ||

separating. He won't be living here anymore." | separating. He won't be living here anymore." | ||

| + | |||

"Who will wash his rags?" I asked. | "Who will wash his rags?" I asked. | ||

| + | |||

She reached for me, but I twisted down into the couch with | She reached for me, but I twisted down into the couch with | ||

| Line 513: | Line 615: | ||

slowly, I stopped, shifting imperceptibly from weeping to | slowly, I stopped, shifting imperceptibly from weeping to | ||

exhausted sleep. | exhausted sleep. | ||

| + | |||

I awoke. My mother sat in the dark watching over me. She | I awoke. My mother sat in the dark watching over me. She | ||

led me to the bathroom and washed my face. “Let’s go to the | led me to the bathroom and washed my face. “Let’s go to the | ||

Golden Dragon,” she said kindly. | Golden Dragon,” she said kindly. | ||

| + | |||

When we got there, I was hungry, but when my mother | When we got there, I was hungry, but when my mother | ||

asked what I wanted I plucked at the tablecloth and said, | asked what I wanted I plucked at the tablecloth and said, | ||

"Nothing." | "Nothing." | ||

| + | |||

When the waitress reached for our menus, I scowled and | When the waitress reached for our menus, I scowled and | ||

| Line 527: | Line 632: | ||

letter to letter. I knew the consonants. The waiter brought Laurel's | letter to letter. I knew the consonants. The waiter brought Laurel's | ||

Egg Foo Young, my mother's Moo Goo Gai Pan. | Egg Foo Young, my mother's Moo Goo Gai Pan. | ||

| + | |||

"Anything for the young lady?" | "Anything for the young lady?" | ||

| + | |||

I shook my head, no, with my finger poised on a "D". The | I shook my head, no, with my finger poised on a "D". The | ||

| Line 536: | Line 643: | ||

head as I touched it, the letters spelled dinner. The next word was | head as I touched it, the letters spelled dinner. The next word was | ||

menu. I didn't tell them. They didn't notice. | menu. I didn't tell them. They didn't notice. | ||

| + | |||

I refused fried rice, bits of shrimp, lush green pea pods, | I refused fried rice, bits of shrimp, lush green pea pods, | ||

| Line 541: | Line 649: | ||

like them. They, who didn't know I could read, they, who couldn't | like them. They, who didn't know I could read, they, who couldn't | ||

manage to live with my father. | manage to live with my father. | ||

| + | |||

My father, who had left me. | My father, who had left me. | ||

| + | |||

The grownups, who didn't know. | The grownups, who didn't know. | ||

| + | |||

▼▪▲ | ▼▪▲ | ||

| + | |||

For a year, I saw my father on weekends. Saturday | For a year, I saw my father on weekends. Saturday | ||

morning, he would pick me up. From the New Yorker, which he had | morning, he would pick me up. From the New Yorker, which he had | ||

| Line 556: | Line 668: | ||

was going to move far away, to San Francisco, where he'd been | was going to move far away, to San Francisco, where he'd been | ||

offered another job. Then he asked to speak to my mother. | offered another job. Then he asked to speak to my mother. | ||

| + | |||

When she got off the phone, she said, "I suppose he'll | When she got off the phone, she said, "I suppose he'll | ||

charge me with mental cruelty." | charge me with mental cruelty." | ||

| + | |||

Laurel asked, "Tell me, would you charge him with | Laurel asked, "Tell me, would you charge him with | ||

adultery?" I sensed a painful need behind her words. | adultery?" I sensed a painful need behind her words. | ||

| + | |||

“No. It would be too humiliating. For me. For Deborah. And | “No. It would be too humiliating. For me. For Deborah. And | ||

besides, you know I wouldn’t sue him for divorce.” | besides, you know I wouldn’t sue him for divorce.” | ||

| + | |||

“We can have our life. When you’re divorced.” | “We can have our life. When you’re divorced.” | ||

| + | |||

"It will never be safe." | "It will never be safe." | ||

| + | |||

I didn't know what any of this was supposed to mean | I didn't know what any of this was supposed to mean | ||

| Line 574: | Line 692: | ||

you once polished the silver lion crouched on the ivory handle.'' | you once polished the silver lion crouched on the ivory handle.'' | ||

| + | |||

▼▪▲ | ▼▪▲ | ||

| + | |||

That summer, Pinny sent the only gift she ever gave me, | That summer, Pinny sent the only gift she ever gave me, | ||

the Black and White Scotties, with a note: | the Black and White Scotties, with a note: | ||

| + | |||

Dear Deborah, | Dear Deborah, | ||

I found these in my jewel box and thought | I found these in my jewel box and thought | ||

of you, such a beautiful little girl. | of you, such a beautiful little girl. | ||

| + | |||

I put the Scotties in my own jewelry box and didn't tell my | I put the Scotties in my own jewelry box and didn't tell my | ||

mother or Laurel. I was embarrassed by how beautiful I had once | mother or Laurel. I was embarrassed by how beautiful I had once | ||

thought the three women, scandalized that Pinny applied that | thought the three women, scandalized that Pinny applied that | ||

same word, beautiful, to me. | same word, beautiful, to me. | ||

| + | |||

| − | + | ==Continued at: [[Faith S. Holsaert: "Chosen Girl," 2003 - Part II]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Start date::June 1, 2003|.]] | ||

| + | [[Category:African American]] | ||

[[Category:Building a Post-War World, 1945-1970]] | [[Category:Building a Post-War World, 1945-1970]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Holsaert, Faith (1950 - )]] |

[[Category:Lesbian]] | [[Category:Lesbian]] | ||

| + | [[Category: literature]] | ||

[[Category:20th century]] | [[Category:20th century]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 16:21, 7 August 2011

Reprinted with the permission of Faith S. Holsaert. Copyright (c) 2003 by Faith S. Holsaert. For reproduction rights contact author at: writerwk1@mac.com

L to R: Shai and Faith Holsaert, Charity Bailey. All photos courtesy of Faith Holsaert.

Introduction by Jonathan Ned Katz

This long short story (80,000 words), set in the 1950s, in progressive, literary {{#set: GPS Place={{#geocode: Greenwich Village}}}}{{#set: Place=Greenwich Village}}{{ #if: |{{{2}}}|Greenwich Village }}, subtly evokes the loving, conflicted, and ultimately thwarted intimacy between two women, one white and the other African American, as seen through the eyes of the white woman's smart, observant daughter. The three live together.

The story communicates the McCarthy-era fears, casual racism, and homophobic pressures of this particiular time and place (and as I personally recall them -- as a child I lived on the same street as Holsaert and knew her family).

The writer, Faith Holsaert, was raised with her sister Shai on Jane Street, in the Village, in a two-mother family by their Jewish mother by birth, Eunice Holsaert, and Charity Bailey, their mother by affection. Bailey was the music teacher at the Little Red School House where Faith was enrolled, and Bailey later hosted a children's TV show in New York City.

I also attended "Little Red," as we called this private "progressive school," and fondly remember gentle but firm "Charity" (we called most of our teachers by their first names). I recall her visiting my family, and discussing the history of Black spirituals with my father who knew much about African American history and culture. I also recall Charity radiating concern for and kindness toward young people, a kindness to which I especially responded.

I also remember coming home from one 1950s visit to Charity Bailey's and Eunice Holsaert's apartment and my mother asking, circumspectly, without explanation, how many beds there were. Annoyed at her prying suspicion, and her asking me to inform on a beloved teacher, I think I said: "Two." I understood vaguely, I think, that my mother was inquiring whether the two women slept together, and that, if true, this was bad. Like much fiction, "Chosen Girl" seemingly contains more than a few autobiographical elements.

Faith Holsaert has published numbers of stories and memoirs, mostly in small literary journals. “Chosen Girl” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. “Creekers” (fiction) won first place in the Kentucky Writers Coalition Competition, in 2004. That year, “Freedom Rider, circa 1993” (fiction) won third place in the Fugue Annual Contest in Prose. “History Dancing,” a memoir, appeared in the autumn of 2006, in a collection published by University of Iowa Press.

I highly recommend this sensitive, wonderfully written art about history. I'm also pleased to honor the memory of Charity Bailey, who, I like to think, had she lived into the present, could have understood our need to look back and specify what we see. "Chosen Girl" is also available in paginated form (48 pages) on the 2004 edition of the web publication The King's English (pages 7-55).[1]

"Chosen Girl" by Faith S. Holsaert

I.

In the beginning were my parents, shoulder to shoulder, the baby floating within their massed outline.

I sat close, in either lap, during their disputes.

My father said, "Oliver Twist. It's a wretched book, Deirdre.

You like it because you read it as a child."

"I like it because it's about people. Not like your Eliot, who

writes about things."

"Deirdre, Fagan's a sentimental abomination."

She held me tight against her bosom, and I learned how her

muscles tightened when she clenched her teeth. “Well I love that

book.”

“Fagan’s an anti-Semitic stereotype,” said my WASP father.

She struck quickly. “Are you Virginia Woolf to my

Leonard?” My Jewish mother.

Silence.

That was the form. Books and books and books. A book to

say I love you. A book to say I hate you. Later, they attacked one

another, down to the muscles of the hands that held me, saying

names like Henry James, Robert Browning. When they agreed,

Auden. The way they loved me was to teach me what they knew.

And what they knew was books.

Before I could read, my father taught me how to open a

new book. First I must riffle the pages, feel the paper with my

fingertip, and smell the lingering odor of ink. His fingers were

tapered, cool half moons at the base of each ridged nail. His hand

warm. I must: open near the beginning of the book; press the

book open until the spine gave; move through the pages in

quarter-inch increments to crack the spine until the book lay

supple and ready in my hand.

Books were their lifeblood. Later, Laurel would say the same

about the blues.

▼▪▲

At four, I drew a scowling face on black construction paper

with waxy red. My mother asked, "What is it?" I said, "The Angry

Mother." My mother wrote, The Angry Mother, in pencil. I didn't

like the silver graphite letters on my dull black paper with my

scrawled red.

That evening over drinks, she showed it to my father. I

snatched it from her.

"It's mine," I said.

She crushed my hands in hers. "Don't interrupt."

"I hate you," I screamed.

"A touch of the angry child?" my father asked, with a smile

as thin as the slivered almond he fed me.

My mother knelt in front of me and stared rudely into my

eyes. "You will say you're sorry."

I wouldn’t, so I was sent to my room.

I stared angrily at photos of my mother and her two

brothers and sister, each mounted within a sepia oval. Her older

brother, at age five or six, was in a sailor suit; the younger brother

smiled from blonde curls and skirts; the sister at age seven or so,

looked out from her oval with a studied gaze, chin propped on a

ringed hand; my mother, a toddler, scowled from her oval, light

tulle clutched to her bosom.

In the light from my bedside lamp, when I tilted my drawing

with its red image, the silvery caption slid off the page.

▼▪▲

Laurel, the music teacher.

In my first memory of her, I stood beside the upright piano

in the nursery classroom. The piano strings jangled. I could see the

lines in the skin on the back of her hand as Laurel played absently.

It was a hand smaller than my father's, squarer than my mother's.

I reached out to touch it and she laughed and struck the keys. She

took my hand, pushed my finger onto a key. A puny sound. She

said my voice was as soft as this -- she plinked, the highest note. I

went home and told my parents I wanted Laurel to live with us.

“She is colored,” my mother said.

“Colored?” I shrilled.

“Haven't you noticed her skin?” my father asked.

I looked at my own hand. “Look,” I thrust it at my parents.

“I'm flesh colored.” From the box of crayons.

▼▪▲

At the first PTA meeting, as a pleasantry, my parents told

Laurel I wanted her to come live with us.

"Do you have a room?" she asked.

When my mother told me this, I demanded, "Are we going

to?"

"We'll see," she said.

In a few weeks, my mother said, "This afternoon, Laurel

and her sister are calling. When they arrive, you must shake

hands. You may say either 'How do you do?' or 'Pleased to meet

you.'"

“Grown-ups don’t want to shake my hand.”

She looked me in the eye, the way cats and children hate to

be stared at. "You will do it."

Laurel arrived with her sister, a fine lady in a copper and

black skirt that rustled.

"Pinny, for the poet Pindar," Laurel said when she

introduced her sister. The sisters said, "No, thank you," to stingers

in long-stemmed glasses.

"Are you going to move in?" I asked Laurel, who said, "We'll

see."

The grown-ups looked at the extra bedroom and returned to

sit in the living room.

"Did you like it?" I asked, but they ignored me.

It was the end of the afternoon and I remember the three

seated women looked as easy and elegant as the phrase, women

of leisure. My mother sat in the armchair opposite Laurel and

Pinny, who wore skirts. My mother wore trousers, belted about her

waist, so small where her pearly blouse tucked into the gabardine,

so small below her heavy breasts. She shook out a match with her

large hands, on which the veins and muscles hung like vines. My

mother explained to Pinny that my name was pronounced De borr

ah, not Debra. Unlike three other girls in my class who were named

after movie stars, I had been named for the Bible's desert warrior

and judge. My mother spoke through cigarette smoke, eyeing the

sisters skittishly over the beak of her nose, blue-black hair falling

in one eye.

"Deborah, come see," Pinny said, and rummaged in her

purse, which smelled of perfume and not of money and tobacco

crumbs, like my mother's. My mother and Laurel talked. On the

palm of her hand, Pinny held two inch-long metal dogs, one black,

one white.

"What are they?" I asked.

"The Black and White Scotch Scotties," Pinny said.

“What’s that?”

“A promotion,” Laurel said.

“To sell scotch. Liquor,” my mother said.

None of it made sense, but I let it go when Pinny said,

"Look.” She held the dogs nose to nose. Forcefully they whirled

around, tail to tail. She asked if I could make them stand nose to

nose. Her tea colored hands over mine, I tried it. The magnetized

Scotties pivoted in my hand. They'd jump from my hand before

they'd face one another.

▼▪▲

Sick in bed with the measles, I imagined monkeys climbing

up and down my bedroom door, pointing at me and jabbering. It's

imaginary, I told myself, but the monkeys screamed so shrilly and

they pointed their hairless fingers at me so believably, I screamed

and interrupted my parents' and Laurel's dinner.

My mother came to sit by my bed.

"Tell me a story," I begged.

"At the turn of the century, your grandparents' families

settled on the Lower East Side," she began. "When he was a boy,

your grandfather sold all-day suckers at Coney Island. He caught

rides with farm wagons from Manhattan to the beach. One day,

only half of his suckers sold, he paused to watch a man in red

tights and big black mustache high on a tightrope. What the man

did was marvelous to your grandfather: he took a little stove from

a pretty lady, and he made pancakes right there, in the air. Your

grandfather Ben was hungry and the pancakes made his mouth

water. After the act, Ben approached Biaggio the tightrope artist

and said, 'People do not believe you are really making pancakes.'

Biaggio frowned fiercely. Ben continued, 'Toss your pancakes to me

in the crowd and I will eat them, to prove they are real.' Biaggio

agreed. The pancakes were delicious and the people loved Ben's

role. They threw more coins to the lady in the tights than they ever had. That day, your grandfather sold all his suckers, was given

money by Biaggio, and he ate all those pancakes, too. That night

the family ate a fat chicken purchased with his earnings."

The monkeys had scampered off. I drank ginger ale and

drifted in and out of sleep.

"Your grandfather bought his first book, the complete works

of Shakespeare, from a book cart in the street. He paid twenty-five

cents down, and ten cents a week.”

The pillows were full and smooth, for my mother had

changed and plumped them.

"Your grandfather proposed to your grandmother."

"The Dowager," I interjected.

"So your father calls her. Ben proposed in front of an ash

can on Delancy Street when he was twelve. He thought her the

prettiest girl in the world."

"Was he right?"

But I didn't hear her answer. I slept.

I awoke. She and Laurel sat in my room.

Laurel was saying, "...papers of manumission and settled in

Rhode Island."

"I don't think of Negroes as coming from New England," my

mother said. "But the way you say 'heart,' is a dead giveaway."

"Just because you mispronounce 'hot.'" Laurel did not

release the “R” from her throat.

"I mispronounce 'heart'?" My mother ground down on the

“R” with gusto. She laughed -- ha hah!

In my fever, I drifted through cool ether, gazing down upon

their slight figures. The cold pinched out my sight and then I

blinked back into awareness.

Laurel said, "Every Saturday, my father and I went to the

farmers' market. In summer, he would go through bushels of corn. He was very particular about his corn. He'd discard them over his

shoulder, right and left, saying contemptuously, 'For the horses.

For the horses.'" My mother laughed again. "I was so

embarrassed," Laurel said. "An ex-slave, rejecting the white

farmers' corn."

"But that's wonderful." My mother whooped. "'For the

horses,'" she parroted. She threw back her head to laugh. Her

laughter gleamed. Laurel laughed, too. Together, they laughed and

wiped their eyes, unseemly as the sweat in which I lay.

A red flannel fever engulfed me. I regained consciousness

chattering and half naked on the bed. Alcohol seared my skin. I

screamed when my mother put the wash cloth on my back. My

arms and legs shook. She pulled a sheet over my legs. She moved

the sheet and parts of my body as she sponged and called me her

chipmunk. She turned me. Finished, she slid me onto a clean,

ironed sheet. She balled up the soiled sheets and threw them in

the hamper.

I was too sick for family stories. She opened a chunky book

and said, “Edna St. Vincent Millay.” I’d never heard these four

words. I barely heard them then, but slipped into the clean cool

words issuing from within the cloud of her cigarette smoke.

Sighing winds, cool earth, dripping apple trees, and the

repose of a child come home. How I relaxed into that home, but

then Millay’s words turned on me, forcing me into the fires of Hell.

I couldn’t cry to my mother: Stop. Hot.

I slept.

The next day, I continued sick.

"When I was twelve," my mother said, "I had a massive

collie named Bud. Bud had been abused by the cab driver who

owned him. My middle brother won him at cards and gave him to

me. Bud snarled at me, and my brother pulled off his belt and

thrashed the dog. Then he told me, 'You must praise Bud when he

is good and he will never snarl at you again.' Bud loved me so

much and I him, we could read one another's minds. Every day, he

and I walked around the Central Park Reservoir without a leash. He

was bigger than a timber wolf. One day, a cop approached us on

Amsterdam Avenue. It was illegal to walk a dog without a leash. I

put my hand on Bud's ruff and said, 'Meet you around the block,

Bud.' He turned and walked away from me. I walked ahead, past

the policeman, turned right at the next corner and as soon as I

turned right at the second corner, I saw Bud walking sedately

toward me on his dainty white feet."

As the afternoon progressed, my fever rose in spite of the

ginger ale, the ice cream, the sponging. Like my fever, my

mother's narrative turned dangerous. She must have thought I

slept. "My older brother cornered me in the corridor and pushed

against me. Bud appeared in the doorway and ripped out the seat

of his pants. Mother didn't believe me when I said, 'He was kissing me like Daddy kisses you,' but my middle brother believed me and

of course, Buddy knew.”

The stories came one after the other, strung together by

nothing but my mother herself, touching end to beginning to end.

"My mother was a grand lady for an immigrant. No one loved her

except my father. She was vain about her tiny feet, which she

wore stuffed into heels with names like Cuban and Stacked and

French. Without her high heels, she was a cripple; her Achilles

tendon had shrunk. And she was vain about her children, so vain,

she starved me.” My mother gulped smoke. “When I was a toddler,

I was all eyes and bone. The Dowager would give me neither

chocolate nor eggs. I was too sallow already, she said, and these

rich foods would make it worse. My mother, with her little blue

eyes and tiny feet, took me to an American doctor. 'Why won't my

baby grow?' she demanded.

"'She's malnourished.' said the doctor. 'Feed her, Madame.

Feed her. Eggs. Milk. Chocolate.'” My mother stubbed out a

cigarette, started another, absorbed in herself, the malnourished,

sallow child. I pulled the sheet back over my shoulder as she

stared into the distance.

"Others found me attractive enough, especially as I

matured. The primitive. A famous theatrical director fell in love

with me when he saw me walking Buddy in the park. We spent

many evenings after the show walking from the theater to my

parents’ apartment. His father, who was a syphilitic maniac, made

the director give me up. The newspaper pictures of the three

successive women he married all looked like me." She laughed

bitterly. "He was weak in everything except his devotion to his

father.”

I stirred to tell her I was awake.

"When I was in my twenties, some of my friends called me

The Bedouin," she said through her film of smoke. I could tell this

nickname pleased her, for she smiled when she said it. "Names,

Deborah, are important. If you had been a boy, I would have

named you Spinoza."

Thank goodness I was a girl.

Days passed. I enjoyed the afternoon baths in dissolved

baking soda. My mother made me what she called an eyrie in her

bedroom window, so I could watch people walking in the street

below. She cut my hair and sent the wisps floating, "for the

sparrows to put in their nests." The week of attention and stories

was drawing to an end. The doctor had said I could go outside the

next day.

"How come you look so angry?" I asked and pointed to the

photo of my mother I’d studied the night of the Angry Mother.

Such a big-eyed little girl with tulle clutched to her naked bosom,

scowling furiously. Above her were pictures of my uncles -- on a

pony with ringlets was the molester and with a violin was the

merciful middle brother. To the side was the sister, dead before my

birth, whom my mother once sadly said was a nymphomaniac.

My mother said, "In those days, all babies were

photographed naked on rugs. When the photographer tried to take

my picture that way, I wouldn't lie down for him. Finally, your

grandmother threw the tulle over my shoulders and he took his

goddamn picture."

▼▪▲

In the beginning, I had rested within the massed outlines of

my mother and father, but then Laurel came. Laurel called me,

“my girl,” and held my hand in her short, broad one which was so

warm. Laurel and my mother were close as breath the night of the

fever monkeys, but my father hadn’t come upstairs that night. He

stopped arguing about books with my mother.

I wished he’d read to me, as he had used to, but he didn’t.

Instead, he taught me how to polish these things: the silver coffee

urn with a lion crouching over its ivory handle, the mahogany table

top which reflected like a mirror when we were done, and shoes,

mine and his, brown and oxblood. Finished with these chores, we

would wash the rags. He kept a jar of water into which he dropped

leftover slivers of hand soap. He used the resulting soap scum to

wash the rags. His rags came from his worn shirts, which he taught

me to rip into strips. Once, after washing out the rags and leaving

them draped over the bathtub to dry, as we prepared to walk in

Washington Square in our newly polished shoes, he took my hand

and said, "Let's go, Junior."

He was gone so often, I was surprised that he was there on

Christmas morning, wearing pajamas, like the rest of us. He placed

a flat package in shiny green paper with an enormous gold bow

under the tree for me. While I opened this, a collection of poetry

for children, Laurel and my mother opened presents from one another, identical fountain pens they laid side by side on the cherry

side table. My mother handed my father an unwrapped box, liqueur

in miniature chocolate bottles. He said I couldn’t have one because

of the alcohol. “Will it make me drunk?” I asked and he said, no,

not drunk, exchanging a smile with Laurel who, like him, was

sipping eggnog from a glass cup. I picked up one of the two pens.

"You must never use another person's fountain pen," my

mother said. If I ever, ever took her pen from her desk and wrote

with it, even one word, it would be ruined. "The nibs are broken in

to one hand." She let me watch as she filled her pen with its

translucent turquoise ink. She tried it out -- brisk flourishes,

galloping curlicues before she capped it and tucked it in her desk,

before going into the kitchen to join Laurel who had carried her

glass cup in there. I sat down with the colored pencils and creamy

paper which my mother had given me.

In the kitchen, Laurel was talking. Among the welter of

words, I heard damn it and like a daughter and I want.

"Don't say it," my mother said.

Holding up the poetry book, I asked, “Read this,” when

Laurel came out of the kitchen. Instead she sat with me, leafing

through a wide, glossy magazine, Look. She deliberately found a

page and touched the picture of a man whose chest was bedizened

with medals. His eyes squinted and his skin in the black and white

photo was the same color as his uniform. "I was once married to

him," Laurel said.

My father, dressed for a party, came into the room.

"Have you seen Deirdre?" he asked Laurel.

"I'm upstairs," my mother yelled.

"Are you coming?" he snapped.

"You know I hate cocktail parties."

"Are you coming?" he repeated

"Jesus, no." She slammed their bedroom door.

He put on his topcoat and left.

▼▪▲

That spring, my mother forbade me to enter their bedroom.

She said my father was sick with strep throat and that I might

catch it. She took his meals into their bedroom on a tray. After a

few days, I saw the untouched food in the kitchen and realized he

hadn't been home for who knew how long. It was like summer vacation with him gone. Meals got served any time and I got to eat

with the grown-ups. The next time I saw him, my father walked

into the dining room in a pale linen jacket. He had a flower in his

buttonhole.

"Behold, the bridegroom cometh," my mother said.

He looked around the room, as if he expected to see some

of his cocktail friends in the corner beside the cabinet. "I'm going

out," he said.

My mother called me to her. "Your father and I are

separating. He won't be living here anymore."

"Who will wash his rags?" I asked.

She reached for me, but I twisted down into the couch with

my back to the room and cried and cried. Laurel and my mother

tiptoed around. One or the other would call gently, "She's

becoming calm." I didn't care. I would cry my eyes out. Slowly,

slowly, I stopped, shifting imperceptibly from weeping to

exhausted sleep.

I awoke. My mother sat in the dark watching over me. She

led me to the bathroom and washed my face. “Let’s go to the

Golden Dragon,” she said kindly.

When we got there, I was hungry, but when my mother

asked what I wanted I plucked at the tablecloth and said,

"Nothing."

When the waitress reached for our menus, I scowled and

hung onto mine. While Laurel and my mother ate wonton soup, I

ran my fingers over the heavy paper of the menu, skipping from

letter to letter. I knew the consonants. The waiter brought Laurel's

Egg Foo Young, my mother's Moo Goo Gai Pan.

"Anything for the young lady?"

I shook my head, no, with my finger poised on a "D". The

grown-ups plunged serving spoons into their food. After the "D"

came two "N's" and an "R.” "Would you like a taste?" Laurel asked

my mother, who accepted. If I made the sound of each letter in my

head as I touched it, the letters spelled dinner. The next word was

menu. I didn't tell them. They didn't notice.

I refused fried rice, bits of shrimp, lush green pea pods,

kumquats. I refused their weakness. I would never be imperfect,

like them. They, who didn't know I could read, they, who couldn't

manage to live with my father.

My father, who had left me.

The grownups, who didn't know.

▼▪▲

For a year, I saw my father on weekends. Saturday

morning, he would pick me up. From the New Yorker, which he had

marked in red, we would select a museum, a movie, or zoo to

attend. Perhaps Gilbert and Sullivan at the Jan Hus Playhouse. One

week, he phoned on Thursday night to tell me he would soon be

going to Reno for a vacation. He would send me a post card. He

was going to move far away, to San Francisco, where he'd been

offered another job. Then he asked to speak to my mother.

When she got off the phone, she said, "I suppose he'll

charge me with mental cruelty."

Laurel asked, "Tell me, would you charge him with

adultery?" I sensed a painful need behind her words.

“No. It would be too humiliating. For me. For Deborah. And

besides, you know I wouldn’t sue him for divorce.”

“We can have our life. When you’re divorced.”

"It will never be safe."

I didn't know what any of this was supposed to mean

except, Don't think about the musty smell of the rag with which

you once polished the silver lion crouched on the ivory handle.

▼▪▲

That summer, Pinny sent the only gift she ever gave me,

the Black and White Scotties, with a note:

Dear Deborah,

I found these in my jewel box and thought

of you, such a beautiful little girl.

I put the Scotties in my own jewelry box and didn't tell my

mother or Laurel. I was embarrassed by how beautiful I had once

thought the three women, scandalized that Pinny applied that

same word, beautiful, to me.