Difference between revisions of "F.B.I. and Homosexuality: Chronology, Part 2"

(→1960) |

|||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

1964, October 7 | 1964, October 7 | ||

| − | :On October 7, a month before the 1964 presidential election on November 3, District of Columbia Police arrested Walter Wilson Jenkins in a YMCA restroom. He and another man were booked on a disorderly conduct charge.<ref>This entry, and its notes are from Wikipedia, accessed December 2, 2011. White, 367; TIME: "The Jenkins Report," October 30, 1964.</ref> This incident has been described as "perhaps the most famous tearoom arrest in America."<ref>Laud Humphreys, Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1974), 19.</ref> Jenkins paid a $50 fine.<ref>Perlstein, 489</ref> Rumors of the incident circulated for several days and Republican Party operatives helped to promote it to the press.<ref>Dallek, 181</ref> Some newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune and the Cincinnati Enquirer, refused to run the story.<ref> White, 367</ref> Journalists quickly learned that Jenkins had been arrested on a similar charge in 1959.<ref>Dallek, 179, 181. The FBI had reported the 1959 arrest in April 1961.</ref> This earlier arrest made it much harder to explain away the later one as the result of overwork or, as one journalist wrote, "combat fatigue."<ref>Perlstein, 490. The journalist was William White.</ref> On October 14, a Washington Star editor called the White House for Jenkins' comment on a story it was preparing. Jenkins turned to White House lawyers Abe Fortas, the President's personal lawyer, and Clark Clifford, who unofficially was filling the role of White House Counsel. They immediately lobbied the editors of Washington's 3 newspapers not to run the story, which only confirmed its significance.<ref>White, 368. Fortas later emphasized that at the time he did not know the validity of the morals charge against Jenkins. New York Times: "Fortas Asserts Police Need Time to Question Suspects," August 6, 1965.</ref> Within hours Clifford detailed the evidence to the President and press secretary George Reedy, "openly weeping," confirmed the story to reporters.<ref>White 369</ref> Probably forewarned, Johnson told Fortas that Jenkins needed to resign. Anticipating the charge that Jenkins might have been blackmailed, Johnson immediately ordered an FBI investigation. He knew that J. Edgar Hoover would have to clear the administration of any security problem because the FBI itself would otherwise be at fault for failing to investigate Jenkins properly years before.<ref>Perlstein, 491.</ref> Hoover reported on October 22 that security had not been compromised.<ref>Evans and Novak, 480. White, 369-70.</ref> Johnson later said: "I couldn't have been more shocked about Walter Jenkins if I'd heard that Lady Bird had tried to kill the Pope."<ref>White, 367.</ref> Johnson also fed conspiracy theories that Jenkins had been framed. He claimed that before his arrest Jenkins had attended a cocktail party where the waiters came from the Republican National Committee, though the party was hosted by Newsweek to celebrate the opening of its new offices.<ref>White, 367. Dallek evaluates various claims that Jenkins was set up and dismisses them. Dallek, 180-1.</ref> ''The Star'' printed the story and UPI transmitted its version on October 14, and Jenkins resigned the same day. | + | :On October 7, a month before the 1964 presidential election on November 3, District of Columbia Police arrested Walter Wilson Jenkins in a YMCA restroom. He and another man were booked on a disorderly conduct charge.<ref>This entry, and its notes are from Wikipedia, accessed December 2, 2011. White, 367; TIME: "The Jenkins Report," October 30, 1964.</ref> This incident has been described as "perhaps the most famous tearoom arrest in America."<ref>Laud Humphreys, Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1974), 19.</ref> Jenkins paid a $50 fine.<ref>Perlstein, 489</ref> Rumors of the incident circulated for several days and Republican Party operatives helped to promote it to the press.<ref>Dallek, 181</ref> Some newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune and the Cincinnati Enquirer, refused to run the story.<ref> White, 367</ref> Journalists quickly learned that Jenkins had been arrested on a similar charge in 1959.<ref>Dallek, 179, 181. The FBI had reported the 1959 arrest in April 1961.</ref> This earlier arrest made it much harder to explain away the later one as the result of overwork or, as one journalist wrote, "combat fatigue."<ref>Perlstein, 490. The journalist was William White.</ref> On October 14, a Washington Star editor called the White House for Jenkins' comment on a story it was preparing. Jenkins turned to White House lawyers Abe Fortas, the President's personal lawyer, and Clark Clifford, who unofficially was filling the role of White House Counsel. They immediately lobbied the editors of Washington's 3 newspapers not to run the story, which only confirmed its significance.<ref>White, 368. Fortas later emphasized that at the time he did not know the validity of the morals charge against Jenkins. New York Times: "Fortas Asserts Police Need Time to Question Suspects," August 6, 1965.</ref> Within hours Clifford detailed the evidence to the President and press secretary George Reedy, "openly weeping," confirmed the story to reporters.<ref>White 369</ref> Probably forewarned, Johnson told Fortas that Jenkins needed to resign. Anticipating the charge that Jenkins might have been blackmailed, Johnson immediately ordered an FBI investigation. He knew that J. Edgar Hoover would have to clear the administration of any security problem because the FBI itself would otherwise be at fault for failing to investigate Jenkins properly years before.<ref>Perlstein, 491.</ref> Hoover reported on October 22 that security had not been compromised.<ref>Evans and Novak, 480. White, 369-70.</ref> Johnson later said: "I couldn't have been more shocked about Walter Jenkins if I'd heard that Lady Bird had tried to kill the Pope."<ref>White, 367.</ref> Johnson also fed conspiracy theories that Jenkins had been framed. He claimed that before his arrest Jenkins had attended a cocktail party where the waiters came from the Republican National Committee, though the party was hosted by Newsweek to celebrate the opening of its new offices.<ref>White, 367. Dallek evaluates various claims that Jenkins was set up and dismisses them. Dallek, 180-1.</ref> ''The Star'' printed the story and UPI transmitted its version on October 14, and Jenkins resigned the same day. As Anthony Summers points out in his book, Official and Confidential: "J. Edgar Hoover's public attitude on homosexuality was normally at least condemnatory, often cruel. On this occasion, however, he visited Jenkins in the hospital and sent him flowers."<ref>Where was this first reported? Evidence?</ref> |

Revision as of 18:28, 2 December 2011

Continued from: F.B.I. and Homosexuality: Chronology, Part 1

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

1950

1950, February 3

- Photo, Hoover and Tolson, etc. Original caption: FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (right) was reported to have told Senators today that Dr. Fuchs has confessed to giving Russia vital information on assembly of the atomic bomb and some data on the supersecret hydrogen weapon. He is shown talking to reporters after a 3-hour session with a Senate Appropriations Subcommittee. In the center is Clyde Tolson, Associate Director of the FBI. Corbis Images: Stock Photo ID: U928885ACME

1951

- Potter "Queer" (2006): "In 1951, at the request of several federal agencies, Hoover devised the Sex Deviates program, which sought to identify gays and lesbians working in government. This function was expanded in 1953 after a presidential order by Dwight Eisenhower made federal employment of homosexuals illegal".[1]

1952

- "In 1952, . . . a memo [in the FBI's files] noted that Gov. Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, the Democratic Presidential nominee, was one of "the two best known homosexuals in the state." It hardly mattered to Hoover that the informant was a college basketball player under indictment for fixing a game or that his evidence was based only on rumor. What did matter was that Stevenson had spoken out against loyalty oaths, criticized Joe McCarthy, and vetoed a bill that would outlaw the Communist Party in Illinois." [New paragraph.] The Crime Records Division of the F.B.I. leaked the homosexual charge to selected members of the press. Rumors flew wildly across the Presidential campaign. [2]

1952, December

- Dudly Clendinen writes:

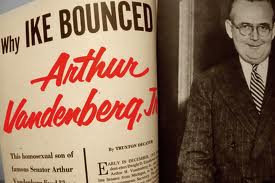

- Just before Christmas in 1952, J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the F.B.I., let President Dwight D. Eisenhower know that the man Eisenhower had appointed as secretary to the president, his friend and chief of staff, my godfather, Arthur H. Vandenberg Jr., was a homosexual.[3] See also: 1956, late.

1953

- The FBI's Sex Deviates program "was expanded in 1953 after a presidential order by Dwight Eisenhower made federal employment of homosexuals illegal."[4] Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450, which mandated the firing of any federal employees guilty of “sexual perversion.”[5]

1953, November 17

- Photo, Hoover and Tolson. Original caption: FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover is shown as he told a Senate Internal Security Subcommittee today that he was notified in February 1947, that Harry Dexter White was being retained in an important international post, so he could be kept under surveillance. He said that his source of information was Tom C. Clark, then Attorney General. Corbis Images: Stock Photo ID: U772154INP

1954, May 22

- Photo, Hoover and Tolson: [http://www.corbisimages.com/stock-photo/rights-managed/U1057939/edgar-j-hoover-and-his-assistant-at?popup=1 Original caption: FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (right) and his assistant Clyde Tolson, at Pilmico Race Track, MD. for running of preakness. Corbis Images: Stock Photo ID: U1057939. Date Photographed: May 22, 1954.

1956, late

- According to Dudley Clendinin, late in 1956, Confidential, "a smut and scandal tabloid probably fed by the F.B.I., published a lurid exposé" about Arthur Vandenberg, Jr. After this, President Eisenhower cut his contacts with Vandenberg, who also resigned from his university job. On January 18, 1968, Vandenberg died at the age of 60, probably a suicide.[6] See also: 1952, December.

1958

- According to a strongly contested account in Anthony Summers' biography of Hoover published in 1993, Susan Rosenstiel said she attended two parties in 1958, at the Plaza Hotel, in New York at which J. Edgar Hoover was dressed as a woman and had sex with men.[7] See 1993.

1960

1964

- Cook, Fred. The FBI Nobody Knows 1964

- What does this say about Hoover's personal life and character?

1964, October 7

- On October 7, a month before the 1964 presidential election on November 3, District of Columbia Police arrested Walter Wilson Jenkins in a YMCA restroom. He and another man were booked on a disorderly conduct charge.[8] This incident has been described as "perhaps the most famous tearoom arrest in America."[9] Jenkins paid a $50 fine.[10] Rumors of the incident circulated for several days and Republican Party operatives helped to promote it to the press.[11] Some newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune and the Cincinnati Enquirer, refused to run the story.[12] Journalists quickly learned that Jenkins had been arrested on a similar charge in 1959.[13] This earlier arrest made it much harder to explain away the later one as the result of overwork or, as one journalist wrote, "combat fatigue."[14] On October 14, a Washington Star editor called the White House for Jenkins' comment on a story it was preparing. Jenkins turned to White House lawyers Abe Fortas, the President's personal lawyer, and Clark Clifford, who unofficially was filling the role of White House Counsel. They immediately lobbied the editors of Washington's 3 newspapers not to run the story, which only confirmed its significance.[15] Within hours Clifford detailed the evidence to the President and press secretary George Reedy, "openly weeping," confirmed the story to reporters.[16] Probably forewarned, Johnson told Fortas that Jenkins needed to resign. Anticipating the charge that Jenkins might have been blackmailed, Johnson immediately ordered an FBI investigation. He knew that J. Edgar Hoover would have to clear the administration of any security problem because the FBI itself would otherwise be at fault for failing to investigate Jenkins properly years before.[17] Hoover reported on October 22 that security had not been compromised.[18] Johnson later said: "I couldn't have been more shocked about Walter Jenkins if I'd heard that Lady Bird had tried to kill the Pope."[19] Johnson also fed conspiracy theories that Jenkins had been framed. He claimed that before his arrest Jenkins had attended a cocktail party where the waiters came from the Republican National Committee, though the party was hosted by Newsweek to celebrate the opening of its new offices.[20] The Star printed the story and UPI transmitted its version on October 14, and Jenkins resigned the same day. As Anthony Summers points out in his book, Official and Confidential: "J. Edgar Hoover's public attitude on homosexuality was normally at least condemnatory, often cruel. On this occasion, however, he visited Jenkins in the hospital and sent him flowers."[21]

1964, November 1-2

- Just before Election Day on November 3, rumors circulated that the GOP would reveal that a member of the cabinet was a closeted homosexual. On a recorded telephone call with the Lyndon Baines Johnson , FBI director J. Edgar Hoover assured LBJ that the rumors were groundless.[22]

- President Johnson: No, I read that. What they said was that—they raised the question of the way he [an unidentified cabinet aide] combed his hair, or the way he did something else, but they had no act of his, or he had done nothing—

- J. Edgar Hoover: No. It was just the suspicion that his mannerisms and so forth were such that they were suspicious.

- President Johnson: Yeah. He [Jenkins] worked for me for four or five years, but he wasn’t even suspicious to me.

- But I guess you’re going to have to teach me something about this stuff!

- Hoover: Well, you know, I often wonder what the next crisis is going to be. [Pause.]

- President Johnson: I’ll swear I can’t recognize them. I don’t know anything about it.

- Hoover: It’s a thing that you just can’t tell. Sometimes, just like in the case of this poor fellow Jenkins . . .

- President Johnson: Yes.

- Hoover: [continuing] There was no indication in any way.

- President Johnson: No.

- Hoover: [continuing] And I knew him pretty well, and [FBI White House liaison Deke] DeLoach did also, and there was no suspicion, no indication.

- There are some people who walk kind of funny and so forth, that you might kind of think are little bit off, or maybe queer. But there was no indication of that in Jenkins’ case.

- President Johnson: That’s right. [Break.]

- Hoover: So far, I haven’t been able to get any more detail than was given to me yesterday, namely that this man [the alleged closeted homosexual] was a cabinet officer, and will be exposed today.

- Now, I thought of all the cabinet officers that we have—and whom I don’t know personally—but there are none of them that raise any suspicion in my mind.

- President Johnson: None in mine.

1965

- Life magazine. On Rock Hudson's FBI file:

- A 1965 memo "recommends Los Angeles to be authorized to interview movie actor Rock Hudson." Why, exactly? Much of the memo is blacked out, but one uncensored line offers a hint at the reason: "Los Angeles has advised that it is general common knowledge in motion picture industry that Hudson is suspected of having homosexual tendencies." Four years later [1969?], when it was reported that Hudson was to star as an FBI man in a planned (but apparently never made) movie called The Seven File, a memo again mentions the allegations that he was gay. "The Los Angeles Office has been instructed to remain alert concerning all developments."

1965, September 19

- Inman, Richard, a homophile activist battling police extortion of homosexuals in South Florida writes to Mattachine-Washington co-founder Jack Nichols [who is using pseudonym Warren Adkins), stating that he knows via a friend inside the FBI that there was one "boss man of the syndicate's homo shakedown detail for the whole of the U.S." [23]

1965, August 5

- "DETECTIVE AT HOTEL IS HELD IN EXTORTION". New York Times, August 5, 1965.

- A 39-year-old house detective [Edward Murphy] at the New York Hilton was arrested early yesterday as the leader of a gang that had extorted a total of $100,000 from "rich playboys and executives." "The case broke, the police said, with the arrest on March 14 [1965] of John Aitken" for impersonating an officer. On July 25 [1965] William Burke was arrested for impersonating an officer.

- Carter, Stonewall (June 2004) suggests that Murphy headed a national blackmail operation that had or knew of evidence against Hoover and Tolson.

- The last article in the Times that mentions Edward Murphy is: Roth, Jack. "NINE SEIZED HERE; Hogan Says Gang Preyed on Homosexuals and Others". New York Times, February 18, 1966.

- Nine members of a nationwide ring that included bogus policemen who preyed primarily on homosexuals to extort money on threats of arrest were taken into custody here yesterday . . . ."

- Among the defendants in custody was "Edward Murphy, 41 years old, of 167 Christopher Street, a former hotel security guard . . . ."

1966, August 17

- "Blackmailer [John Felebaum] Gets Five Years in Homosexual Case". New York Times, August 17, 1966.

- "Assistant United States Attorney Andrew J. Maloney said one of the ring's victims had committed suicide after being interviewed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He did not identify the victim."

1968

- Shortly after Richard Nixon's election victory in 1968, he ordered an adviser, John Ehrlichman, to establish immediate White House contact with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Mr. Ehrlichman phoned J. Edgar Hoover, the bureau's legendary Director, who invited him to his office. Bored by Hoover's conversation, Ehrlichman wondered how anyone could take this man seriously. "A few weeks later, Hoover phoned the President. There were rumors, he said, about homosexual activity "at the highest levels of the White House staff." They came from a bureau informant, who had mentioned Ehrlichman. Of course, the F.B.I. would check out these rumors if the President so ordered. He did. The rumors proved false. But Hoover had sent his calling card. Mr. Ehrlichman would not take him lightly again."[24]

1968

- The Homosexual Handbook, published in 1968, has a last chapter titled "Uncle Fudge's List of Practical Homosexuals Past and Present . . ." that includes the name of J. Edgar Hoover on page 267. Carter, in Stonewall (June 2004), says that "After the book appeared, pressure from the FBI caused it to be withdrawn." The publisher soon reissued the book, but without Hoover's name.[25]

1969, June 24

- Potter. "Queer" (2006): "President Nixon’s aide H. R. Haldeman noted in his diary [of this date] what was likely a regular occurrence: “Hoover . . . reported to [Attorney General John] Mitchell that columnist Drew Pearson had a report that [John] Erlichman, [Dwight] Chapin, and I had attended homosexual parties at a local Washington hotel. Pearson was checking before running the story . . . [and so] at Mitchell’s suggestion, we agreed to be deposed by the FBI to clear this up.”[26]

1960s, late

- "It is possible that the first published allegation of Hoover’s homosexuality appeared in the late 1960s in Al Goldstein’s sex tabloid, Screw"[27]

1970

1970, January 1

- Life Magazine. Caption: "(L-R) FBI dir. J. Edgar Hoover and his asst. Clyde Tolson looking at menus in the Mayflower Hotel where they lunched together each workday for 40 years." [Looking pained; identical pepper grinders; identical suits.] Time Life Pictures/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images Jan 01, 1970.[28]

1971, October 18

- “I emphatically deny that I have at any time under any circumstances ever said or remotely suggested that Mr. Hoover was a homosexual,” [reporter Jack] Nelson wrote [to Hoover] on Oct. 19, 1971. [29]

1972, May 4

- Photo: Original caption:Clyde A. Tolson, Associate Director of the FBI, is helped to his car, after attending burial of his life-long friend, J. Edgar Hoover, in the Congressional Cemetery. Shortly thereafter, Tolson submitted his resignation, citing "ill health." Tolson is a native of Laredo, Montana. Corbis Images: Stock Photo ID: U1738097. Date Photographed: May 4, 1972

1974

In an article asking "Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?" Al Goldstein, in Screw magazine, took on the FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in print. Goldstein soon had to face charges in Kansas. FULL RELIABLE CITATION?

1975

- "revelations, in the 1975 Senate investigations led by Frank Church of Idaho, that the CIA and FBI had been engaged in long-term intelligence gathering operations against its own citizens and domestic political groups"[30]

1977

- Cohen, Larry. The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover. Film directed by Larry Cohen.[31]

- "In 1977, Bureau officials added more gaps to the paper trail by destroying the 300,000 pages in the "Sex Deviate Program."[32]

1978

- Powers, Richard Gid, “One G-Man’s Family: Popular Entertainment Formulas and J. Edgar Hoover’s F.B.I.,” American Quarterly 30, no. 4 (1978): 471–92.

1978, May

- Bell, Arthur. "Skull Murphy: The Gay Double Agent". Village Voice May 1978, pages 1, 17-19.

- Bell, page 1.

- Bell, page 17.

- He says he started informing undercover for the FBI in 1965 about a national ring blackmailing homosexuals. Murphy says that J. Edgar Hoover "was one of my sisters. He was the biggest fuckin' extortionist in this country. He had presidents by the balls. He had a record on everybody and his brother." He adds: "Every thing I know [about mobsters] is on file at certain law enforcement agencies for certain people who are doing investigations."

- Bell, page 18.

- Bell, page 19.

- My double agent days started in '66 with the extortion ring. It was supposed to be a one-shot deal. We locked up 21 guys. They're all dead now, except three of them."

- Carter says that Murphy says that the Mafia had photographs of Hoover involved in sex acts.[33] Photographs are not mentioned in the Bell interview--JNK

Next: F.B.I. and Homosexuality: Chronology, Part 3

See also:

F.B.I. and Homosexuality: A History MAIN PAGE

F.B.I. and Homosexuality: Bibliography

F.B.I. and Homosexuality: Chronology, Part 1

F.B.I. and Homosexuality: Persons and Groups Investigated

Notes

- ↑ Potter "Queer" (2006), page 368.

- ↑ David M. Oshinsky, "The Senior G-Man", New York Times, September 15, 1991.

- ↑ y. "J. Edgar Hoover, ‘Sex Deviates’ and My Godfather". New York Times, November 25, 20011.

- ↑ Potter, "Queer" (2006), page 368.

- ↑ Clendinen, Dudly. "J. Edgar Hoover, ‘Sex Deviates’ and My Godfather". New York Times, November 25, 20011.

- ↑ Clendinen, Dudly. "J. Edgar Hoover, ‘Sex Deviates’ and My Godfather". New York Times, November 25, 20011.

- ↑ Potter, "Queer Hover", 355-356: This account is taken from Anthony Summers, Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1993), 253–55.

- ↑ This entry, and its notes are from Wikipedia, accessed December 2, 2011. White, 367; TIME: "The Jenkins Report," October 30, 1964.

- ↑ Laud Humphreys, Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1974), 19.

- ↑ Perlstein, 489

- ↑ Dallek, 181

- ↑ White, 367

- ↑ Dallek, 179, 181. The FBI had reported the 1959 arrest in April 1961.

- ↑ Perlstein, 490. The journalist was William White.

- ↑ White, 368. Fortas later emphasized that at the time he did not know the validity of the morals charge against Jenkins. New York Times: "Fortas Asserts Police Need Time to Question Suspects," August 6, 1965.

- ↑ White 369

- ↑ Perlstein, 491.

- ↑ Evans and Novak, 480. White, 369-70.

- ↑ White, 367.

- ↑ White, 367. Dallek evaluates various claims that Jenkins was set up and dismisses them. Dallek, 180-1.

- ↑ Where was this first reported? Evidence?

- ↑ [http://allthewaywithlbj.com/the-jenkins-scandal/ Adapted from AllTheWayWithLBJ.com, accessed December 2, 2011.

- ↑ Carter, Stonewall, pages 93-94, note 8 page 286, citing James T. Sears, Lonely Hunters: An Oral History of Lesbian and Gay Southern Life, 1948-1968 (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1997), p. 244. Carter suggests that the boss man in question is Edward Murphy.

- ↑ Oshinsky, David M. "The Senior G-Man". New York Times, September 15, 1991, citing Ehrlichman's memoirs.

- ↑ Cartner, Stonewall, pages 94-95, citing in note 10, page 286: Straight News, page 269, and Donn Teal, The Gay Militants, pages 65.

- ↑ Potter. "Queer" (2006), page 369 citing H. R. Haldeman, The Haldeman Diaries: Inside the Nixon White House (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1994), 66.

- ↑ See Gay Talese, Thy Neighbor’s Wife (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1980), 229. Cited in Potter, Queer, page ?

- ↑ http://www.life.com/news-pictures/50613576/clyde-a-tolsonj-edgar-hoover

- ↑ For full story see: Serrano, Richard A. Serrano, "An FBI director with a grudge". Los Angeles Times, November 6, 2011, 8:03 p.m. (on this list), and "Hoover worried"

- ↑ Potter, "Queer" (2006), page 381.

- ↑ Poveda and others (1998), page 291.

- ↑ David M. Oshinsky, "The Senior G-Man", New York Times, September 15, 1991.

- ↑ Cited in Carter, Stonewall, note 3, page 285.