Difference between revisions of "Loring Park"

| (5 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | {{unprotected}} | ||

{| {{prettytable}} | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

! | ! | ||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

| − | Minneapolis’ booming population and the development of affordable public transportation fueled urban expansion by 1900. The area changed drastically in just three decades, when wealthy residents vacated the Loring Park area and settled atop Kenwood Hill, leaving Loring open for dense development. In the 1910s and 20s, mansions gave way to familiar uses: apartment hotels, early auto dealerships, office buildings, and apartment houses. With this change came a concurrent change in the park’s populations and activity. | + | Minneapolis’ booming population and the development of affordable public transportation fueled urban expansion by 1900. The area changed drastically in just three decades, when wealthy residents vacated the Loring Park area and settled atop Kenwood Hill, leaving Loring open for dense development. In the 1910s and 20s, mansions gave way to familiar uses: apartment hotels, early auto dealerships, office buildings, and apartment houses.<small>(2)</small> With this change came a concurrent change in the park’s populations and activity. |

| − | Many extant queer neighborhoods cannot establish a beginning to their queer activity, and Loring Park is no exception. Community historian Robert Halfhill suggested that cruising visibly began after the Second World War’s end<small>( | + | Many extant queer neighborhoods cannot establish a beginning to their queer activity, and Loring Park is no exception. Community historian Robert Halfhill suggested that cruising visibly began after the Second World War’s end<small>(3)</small>—and this is likely true—yet the [[Gateway District]] remained the core of queer Minneapolis until its demise in the early 60s. Loring Park was likely a residential settlement, as opposed to the purely bar-based Gateway—It came to eminence as newly Gay-identified men created community needs for their neighborhood. |

| Line 32: | Line 33: | ||

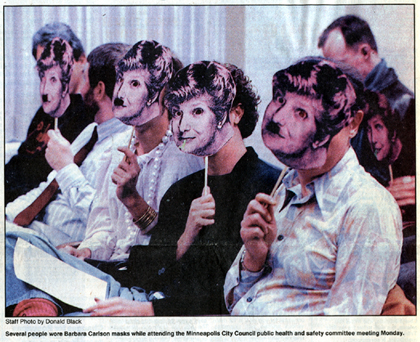

<small>'''Minneapolis City Councilperson Barabara Carlson, who represented Loring Park in the late 1980s, was admonished by Loring Park residents for her support of an anti-cruising ordinance. Photo from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | <small>'''Minneapolis City Councilperson Barabara Carlson, who represented Loring Park in the late 1980s, was admonished by Loring Park residents for her support of an anti-cruising ordinance. Photo from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | | This “Gay Ghetto” survived until the late 1970s and comprised three camps: middle-class men lived in “Homo Heights” on or near Ridgewood; the poor lived East of Willow Street to Steven’s Square; and the wealthiest residents were dallying married men who lived in the “Homolayas,” also known as Kenwood Hill. | + | | This “Gay Ghetto” survived until the late 1970s and comprised three camps: middle-class men lived in “Homo Heights” on or near Ridgewood; the poor lived East of Willow Street to Steven’s Square; and the wealthiest residents were dallying married men who lived in the “Homolayas,” also known as Kenwood Hill.<small>(4)</small> |

| − | While cruising is no longer the park’s mainstay, Loring is home to the [[Twin Cities Pride Festival]] and remains the cultural heart of the queer community. | + | While cruising is no longer the park’s mainstay, Loring is home to the [[Twin Cities Pride Festival]]<small>(5)</small> and remains the cultural heart of the queer community. |

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | ==This entry is part of:== | ||

| + | == [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-2010)]]== | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| Line 45: | Line 51: | ||

<small>(1)</small>Millet, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007. Page 80. | <small>(1)</small>Millet, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007. Page 80. | ||

| − | <small>(2)</small>Halfhill, Robert. "Loring's Gay and Lesbian Communities." From ''Reflections in Loring Pond: A Minneapolis neighborhood examines its first century.'' Minneapolis: Citizens for a Loring Park Community: 1986. Page 156. | + | <small>(2)</small>''Ibid.'' |

| + | |||

| + | <small>(3)</small>Halfhill, Robert. "Loring's Gay and Lesbian Communities." From ''Reflections in Loring Pond: A Minneapolis neighborhood examines its first century.'' Minneapolis: Citizens for a Loring Park Community: 1986. Page 156. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>(4)</small>Doctherman, Robyn. "Pride of Place." ''City Pages'': "Q Monthly", 6/1/1998. http://www.citypages.com/1998-06-01/feature/his-day-to-relax/ | ||

| − | + | <small>(5)</small>http://www.tcpride.org/index_main.php | |

Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:25, 2 February 2012

Irregularly shaped by 15th Street, Harmon Place, Willow Street, and Hennepin Avenue

Minneapolis’ booming population and the development of affordable public transportation fueled urban expansion by 1900. The area changed drastically in just three decades, when wealthy residents vacated the Loring Park area and settled atop Kenwood Hill, leaving Loring open for dense development. In the 1910s and 20s, mansions gave way to familiar uses: apartment hotels, early auto dealerships, office buildings, and apartment houses.(2) With this change came a concurrent change in the park’s populations and activity.

Many extant queer neighborhoods cannot establish a beginning to their queer activity, and Loring Park is no exception. Community historian Robert Halfhill suggested that cruising visibly began after the Second World War’s end(3)—and this is likely true—yet the Gateway District remained the core of queer Minneapolis until its demise in the early 60s. Loring Park was likely a residential settlement, as opposed to the purely bar-based Gateway—It came to eminence as newly Gay-identified men created community needs for their neighborhood.

| Minneapolis City Councilperson Barabara Carlson, who represented Loring Park in the late 1980s, was admonished by Loring Park residents for her support of an anti-cruising ordinance. Photo from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

This “Gay Ghetto” survived until the late 1970s and comprised three camps: middle-class men lived in “Homo Heights” on or near Ridgewood; the poor lived East of Willow Street to Steven’s Square; and the wealthiest residents were dallying married men who lived in the “Homolayas,” also known as Kenwood Hill.(4)

|

This entry is part of:

Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-2010)

(1)Millet, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007. Page 80.

(2)Ibid.

(3)Halfhill, Robert. "Loring's Gay and Lesbian Communities." From Reflections in Loring Pond: A Minneapolis neighborhood examines its first century. Minneapolis: Citizens for a Loring Park Community: 1986. Page 156.

(4)Doctherman, Robyn. "Pride of Place." City Pages: "Q Monthly", 6/1/1998. http://www.citypages.com/1998-06-01/feature/his-day-to-relax/

(5)http://www.tcpride.org/index_main.php

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)