Difference between revisions of "Wilson Collection: Same-Sex Desire and the American Slave Narrative"

(Same-sex desire and the American slave narrative) |

(Same-sex desire and the American slave narrative) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Douglass.jpg]] | [[File:Douglass.jpg]] | ||

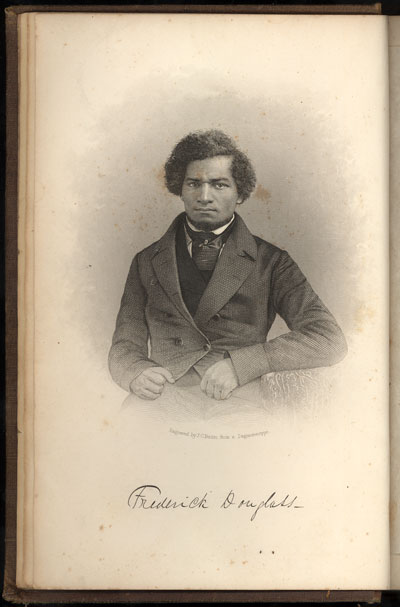

| − | (Frontis portrait of Frederick Douglass and title page from his autobiography, | + | ''(Frontis portrait of Frederick Douglass and title page from his autobiography, |

| − | My Bondage and My Freedom, 1855) | + | My Bondage and My Freedom, 1855)'' |

Under construction. | Under construction. | ||

| − | Same-Sex Desire and the American Slave Narrative | + | '''Same-Sex Desire and the American Slave Narrative''' |

To shed light on same-sex experiences of American slaves, author Charles Clifton suggests re-reading narratives written by former slaves. For instance, in The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, former slave Equiano discloses that, on his passage from Africa, a white co-voyager named Queen “messed with me on board” and “became very attached to me, [saying that] he and I never should part.”[1] Equiano “grew very fond of” another white companion. On many nights they laid “in each other's bosoms.”[2] | To shed light on same-sex experiences of American slaves, author Charles Clifton suggests re-reading narratives written by former slaves. For instance, in The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, former slave Equiano discloses that, on his passage from Africa, a white co-voyager named Queen “messed with me on board” and “became very attached to me, [saying that] he and I never should part.”[1] Equiano “grew very fond of” another white companion. On many nights they laid “in each other's bosoms.”[2] | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Clifton observes “in these passages a familiarity with same-sex relations on the part of the authors.”[6] He remarks that there are many “unchartered areas of research” within “the realm of slave sexuality.”[7] An unbiased “attempt to read…what was not overtly articulated” may unearth relationships that “are not necessarily heterosexual.”[8] | Clifton observes “in these passages a familiarity with same-sex relations on the part of the authors.”[6] He remarks that there are many “unchartered areas of research” within “the realm of slave sexuality.”[7] An unbiased “attempt to read…what was not overtly articulated” may unearth relationships that “are not necessarily heterosexual.”[8] | ||

| − | References | + | ''References'' |

| + | |||

1. Charles Clifton, “Rereading Voices from the Past: Images of Homo-Eroticism in the Slave Narrative,” in The Greatest Taboo: Homosexuality in Black Communities, ed. Delroy Constantine-Simms (Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 2000), 347. | 1. Charles Clifton, “Rereading Voices from the Past: Images of Homo-Eroticism in the Slave Narrative,” in The Greatest Taboo: Homosexuality in Black Communities, ed. Delroy Constantine-Simms (Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 2000), 347. | ||

2. Ibid., 346-347. | 2. Ibid., 346-347. | ||

Revision as of 18:47, 3 November 2012

(Frontis portrait of Frederick Douglass and title page from his autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, 1855)

Under construction.

Same-Sex Desire and the American Slave Narrative

To shed light on same-sex experiences of American slaves, author Charles Clifton suggests re-reading narratives written by former slaves. For instance, in The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, former slave Equiano discloses that, on his passage from Africa, a white co-voyager named Queen “messed with me on board” and “became very attached to me, [saying that] he and I never should part.”[1] Equiano “grew very fond of” another white companion. On many nights they laid “in each other's bosoms.”[2]

About his fellow slaves, Frederick Douglass writes in My Bondage and My Freedom, “No band of brothers could have been more loving.”[3] He leaves un-detailed his “long and intimate, though by no means friendly, relation” with a former slave master.[4] And he alludes to the “out-of-the-way places...where slavery...can, and does, develop all its malign and shocking characteristics...without apprehension or fear of exposure.”[5]

Clifton observes “in these passages a familiarity with same-sex relations on the part of the authors.”[6] He remarks that there are many “unchartered areas of research” within “the realm of slave sexuality.”[7] An unbiased “attempt to read…what was not overtly articulated” may unearth relationships that “are not necessarily heterosexual.”[8]

References

1. Charles Clifton, “Rereading Voices from the Past: Images of Homo-Eroticism in the Slave Narrative,” in The Greatest Taboo: Homosexuality in Black Communities, ed. Delroy Constantine-Simms (Los Angeles: Alyson Books, 2000), 347. 2. Ibid., 346-347. 3. Ibid., 347. 4. Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom. Part I. Life as a Slave. Part II. Life as a Freeman (New York: Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1855), 421. 5. Ibid., 62. 6. Clifton, “Rereading,” 349. 7. Ibid., 358. 8. Ibid., 344, 358.