Difference between revisions of "Jonathan Ned Katz: "Comrades and Lovers""

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

| − | =[http://209.200.244.13/wiki/%22Comrades_and_Lovers%2C%22_Character_List "Comrades and Lovers," Character List]= | + | =[http://209.200.244.13/wiki/%22Comrades_and_Lovers%2C%22_Character_List "Comrades and Lovers," Character List]= |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 20:52, 20 October 2011

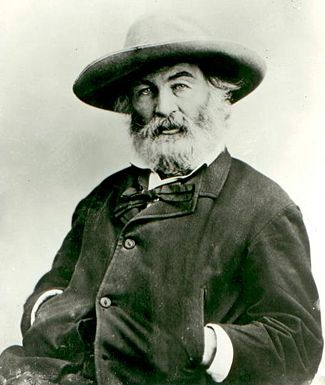

A theater piece about love between men in the life of Walt Whitman

This theater piece is adapted from the words of Whitman, John Addington Symonds, and the others who appear in it, condensed from their letters, diaries, essays, interviews, and poems.

Synopsis

"Comrades and Lovers" explores the conflict between Walt Whitman and John Addington Symonds, the English homosexual emancipation pioneer.

Inspired by Whitman’s Calamus poems of loving lust between men, Symonds pursues Whitman for twenty years, trying to get Whitman to declare, for publication, that he sanctions the active sexual expression of men with men.

In response, the conflicted, crafty Whitman is deeply moved and intrigued by Symonds’ interest in him and his poems, leads Symonds on, and, for many years carefully evades answering him.

Counterposed to Whitman’s conflict with Symonds are the American poet’s happy and troubled intimacies with Fred Vaughan and six “sons” – Thomas Sawyer, Lewis Brown, Douglass Fox, Peter Doyle, Harry Stafford, and Edward Cattell –- as well as with a number of other young working men.

Despite Whitman’s evasiveness with Symonds, Whitman’s poems of amorous comradeship, sent into the world, do encourage ardent physical intimacies between men.

- Encouraged by Whitman's man-love poems, Symonds describes his salutary first experiment in active erotic comradeship.

- Whitman’s man-love poems provide another Englishman, Edward Carpenter, the “ground for the love of men.” Carpenter dedicates his life to making it “more and more possible for men to walk hand in hand over the whole earth.”

Finally, Symonds makes his most explicit attempt to entice Whitman into speaking out publicly for the free sexual expression of men-loving-men, and for the decriminalization of sexual acts between men.

But Whitman’s deep concern to perpetuate his image as “representative” American man and poet -– his intense concern about his image in the eyes of America and posterity –- makes him refuse Symonds' most determined appeal for support in his sex reform effort.

Despite Whitman’s unwillingness to lend his name to Symonds’ sexual emancipation cause, Whitman’s poems continue to encourage physical and loving intimacies between men.

- A young American, Gavin Arthur, details his erotic communion with Whitman’s English disciple, Edward Carpenter.

And, as Whitman feared, the forces of sexual suppression, represented by the Catholic diocese of the poet’s home in Camden, New Jersey, respond negatively to the public revelation of Whitman’s role as homoerotic prophet.

This piece ends with Whitman’s call to and affirmation of all the world’s “comrades and lovers.”

Historical Background

Symond’s asking Whitman to support the right to sexual expression of men with men provided one of the great liberatory opportunities of the nineteenth century, one of those rare moments in which one individual could have stood up to repressive social forces and made a difference.

At that time, however, neither Symonds, Carpenter, nor any other Englishman or American had yet dared to stand up publicly in support of the erotic feelings and acts of men with men –- or for the decriminalization of sexual acts between men. Symonds was asking Whitman for an act of courage that Symonds himself was not ready to take. A few years after Symonds’ death, Oscar Wilde’s public outing as a man-loving-man meant prison, the end of his literary career, martyrdom, and eventual death. Considering those circumstances, Whitman’s failure of courage is comparable to Galileo’s surrender to the Inquisition, as presented by Bertolt Brecht.

Whitman’s tragic failure of nerve, due his concern with reputation and appearances, is a preoccupation with deep present-day resonance, and raises questions for persons of all sexual persuasions.

Yet, in the end, Whitman did send out into the world his exquisite poems of erotic communion between men, poems that encouraged generations of men-loving-men to affirm and act on their feelings. In the end, Whitman did recruit.

Act 1

1 Walt Whitman: "Love thoughts"

2 Rufus Griswold: "Once licentiousness"

3 Walt Whitman: "Through me"

4 Bronson Alcott: "With Henry David Thoreau"

5 Walt Whitman: "By silence"

6 John Addington Symonds: "Is it not strange?"

7 Walt Whitman: "Alone I had thought"

8 John Addington Symonds: "I am taking with me to London"

9 Fred Vaughan: "To form the acquaintance"

10 Walt Whitman: "Passing Stranger!"

11 Walt Whitman, Thomas Sawyer, Lewis K. Brown, Douglass Fox: "Began my visits"

12 John Addington Symonds: "When a man"

Act II

1 Peter Doyle: "Yes, I will talk of Walt"

2 John Addington Symonds: "I fear"

3 Walt Whitman: "It is to the development"

4 Walt Whitman: "City of Orgies"

5 Edward Carpenter: "There are many"

6 Walt Whitman, Harry Stafford, Ed Cattell: "The hour, night"

7 Horace Traubel, "Whitman asked me"

8 John Addington Symonds: "In your conception of Comradeship"

9 Gavin Arthur, "In spite of his eighty years"

10 The New York Times, December 17, 1955

11 Peter Doyle, "I have Walt's raglan"

12 Walt Whitman, "No labor-saving machine"