Difference between revisions of "19 Bar"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

! | ! | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | When built in 1922 as a laundry service on 15th Street West, between Nicollet and Lasalle Avenues, 19 West 15th Street was prime real estate in Minneapolis' burgeoning apartment district. Hidden in the shadows of two immense hotels, the Donald and the Buckingham, the building was steps from the Nicollet Avenue trolley line,<small>(1)</small> the Minneapolis Auditorium, and [[Loring Park]]. It once served a prewar neighborhood of young professionals, visiting businessmen, and newlywed families. |

| − | Non-normative people replaced young nuclear families and wealthy inhabitants in the area following the Depression and WWII.<small>(2)</small> | + | Non-normative people replaced young nuclear families and wealthy inhabitants in the area following the Depression and WWII.<small>(2)</small> In 1956, Harry S. Kirshbaum sold his “Nineteen Bar” to Evrett L. Stoltz, an unmarried resident of Park Terrace Apartments<small>(3)</small>, beginning the 19 Bar’s history as the oldest LGBT-owned bar in the Twin Cities. |

| <div style="text-align: center;"> | | <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

[[Image:Donald_Hotel.jpg]] | [[Image:Donald_Hotel.jpg]] | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| − | The 19 quickly became the epicenter of a vibrant “Gay Ghetto” whose population migrated from the demolished [[Gateway District]] and sought a separatist community. Inhabitants of the “Ghetto” | + | The 19 quickly became the epicenter of a vibrant “Gay Ghetto” whose population migrated from the demolished [[Gateway District]] and sought a separatist community. Inhabitants of the “Ghetto” lused the bar to cruise, often relocating to another location for sex. Because this activity often took place in [[Loring Park]], parked cars, and other public locations, the City of Minneapolis aggressively attempted to close the 19 Bar and demolish its surrounds in the latter half of the 20th century.<small>(4)</small> In part, local officials wished to remove unsavory populations using urban renewal in an attempt to recapture the attention of traditional families.<small>(5)</small> |

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

| − | While Municipal efforts successfully forced much of the queer population out of the area, the 19 Bar survives to this day. Its | + | While Municipal efforts successfully forced much of the queer population out of the area, the 19 Bar survives to this day. Its central role in queer socialization has diminished since the 1950s, yet the bar retains essential elements of its past: a diverse clientele, simplicity, and a good urban location. |

| + | ---- | ||

==This entry is part of:== | ==This entry is part of:== | ||

| − | == [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860 | + | == [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-2010)]]== |

| + | ---- | ||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Latest revision as of 06:07, 17 January 2012

19 West 15th Street, Minneapolis, MN (1956-Present)

| When built in 1922 as a laundry service on 15th Street West, between Nicollet and Lasalle Avenues, 19 West 15th Street was prime real estate in Minneapolis' burgeoning apartment district. Hidden in the shadows of two immense hotels, the Donald and the Buckingham, the building was steps from the Nicollet Avenue trolley line,(1) the Minneapolis Auditorium, and Loring Park. It once served a prewar neighborhood of young professionals, visiting businessmen, and newlywed families.

|

Photo of the former Donald Hotel by Norton & Peel, 1939. 19 West 15th St. is visible in the photo's bottom-left corner. Image Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. |

The 19 quickly became the epicenter of a vibrant “Gay Ghetto” whose population migrated from the demolished Gateway District and sought a separatist community. Inhabitants of the “Ghetto” lused the bar to cruise, often relocating to another location for sex. Because this activity often took place in Loring Park, parked cars, and other public locations, the City of Minneapolis aggressively attempted to close the 19 Bar and demolish its surrounds in the latter half of the 20th century.(4) In part, local officials wished to remove unsavory populations using urban renewal in an attempt to recapture the attention of traditional families.(5)

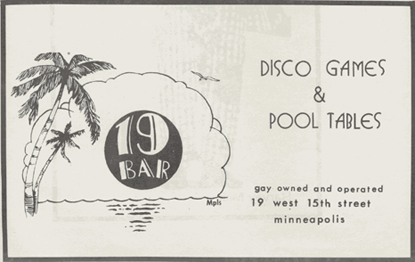

An advertisement for the 19 in the Twin Cities Pride Guide, 1979,

Image courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies

While Municipal efforts successfully forced much of the queer population out of the area, the 19 Bar survives to this day. Its central role in queer socialization has diminished since the 1950s, yet the bar retains essential elements of its past: a diverse clientele, simplicity, and a good urban location.

This entry is part of:

Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-2010)

Notes

(1) Diers, John and Isaace, Aaron. Twin Cities by Trolley: The Streetcar Era in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. Page 249

(2) Millet, Larry. Twin Cities Then and Now. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1996. Pages 64-65.

(2) Minneapolis City Directories, 1950-1960. Hennepin County Public Library: Central Library, 4th floor reference stacks.

(3) "Threat to Close 19 Bar," Published by Robert Halfhill for State Senate: circa 1980. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies.

(4) Trimble, Steve. Reflections in Loring Pond: A Neighborhoods Examines its First Century. Minnesota: Citizens for a Loring Park Community, 1986. Page 132.