Difference between revisions of "Nestle: Blog on History; Women's House of D, 1931-1974"

(The noted author, teacher, and co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives in New York writes an original series of memoirs for OutHistory.org.) |

|||

| (50 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==A City's Shame, A Community's Icon== |

| − | + | by Joan Nestle. Copyright © Joan Nestle 2008. All rights reserved | |

| + | (With this essay noted author and co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Joan Nestle inaugurates OutHistory's series of personal meditative blogs on LGBTQ and heterosexual history.) | ||

| − | |||

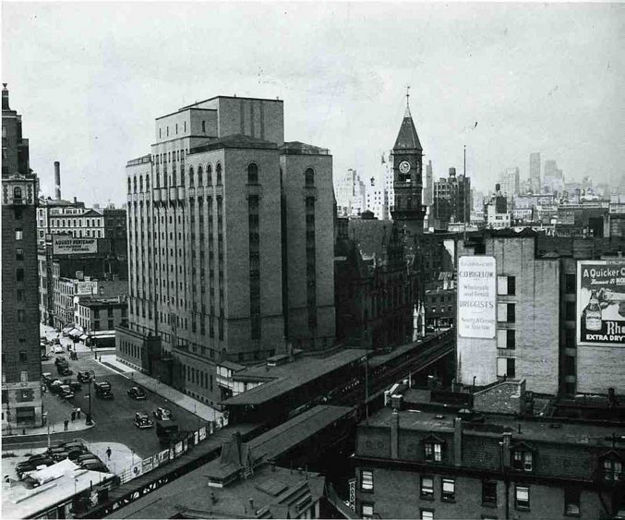

| + | [[Image:Womensd.jpg|thumb|625px|Women's House of Detention, 1938. | ||

| + | <ref>http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GV/GV028JeffersonMarketLibrary.htm</ref>]] | ||

| − | ( | + | The image of the fortress-like building that was the Women’s House of Detention (1931-1974) in Greenwich Village, New York City, has stayed with me all these many years. Fifty years before I read Foucalt, this building and its inhabitants declared to me the connections between deviance, punishment and unrepentent desire. |

| − | |||

| + | First, in the late 1950s and throughout the 60s when I was a young fem woman making my way late at night from my railroad apartment on 9th Street between Avenue A and Tompkins Park, walking across town on 8th Street, my destination the “Sea Colony,” a rough butch-fem bar across from Abington Square — east to west, my route went, and always past the dark medieval building that housed so many poor and working women, so many lesbians. | ||

| − | |||

| + | How to account for what stands solid through the years and changes of geographies, for what will become a basic structure of one’s historical memory? | ||

| − | |||

| + | The hot summer weekend nights that I stood and watched and listened to the pleas of lovers, butch women shouting up to the narrow-slitted windows, to hands waving handkerchiefs, to bodiless voices of love and despair, “Momi, the kids are okay,” marked me then and still do. Here, my sense of a New York lesbian history began, not a closeted one, but right there on the streets. | ||

| − | |||

| + | Tourists taking in the Village stopped and wondered at the spectacle of public women lovers in the midst of neotiating a hard patch in their lives, but neither stares or rude laughter interrupted this ritual of necessary and naked communication. | ||

| − | |||

| + | I stood those days, convinced I was a criminal too, on my way to my haven, a policed place where deviants were kept under a watchful eye, but given a small patch of freedom. From one urban street scene to another, my city was alive with freaks. | ||

| − | |||

| + | In the bar, with that subversive sense of humor that undercuts hardship, the Women’s House of D was called the “Country Club,” and friends were always asking after someone’s woman who was incarcerated. The prison was a presence in our lives—a warning, a beacon, a reminder and a moment of community. | ||

| − | |||

| + | Erected in 1931 on the bones of an older jail and market place, this urban prison reflected the changing penal philosophies of women's punishment that Estelle Freedman wrote so well of in ''Their Sister’s Keepers'', beginning with a progressive plan for the betterment of the incarcerated women and then giving in to disdainful neglect as race and class chased out ideals.<ref>Estelle B. Freedman, ''Their Sisters' Keepers: Women's Prison Reform in America, 1830-1930'' (University of Michigan Press, 1981).</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| + | Dismissed as the prison for hookers, and other "obscenities," city officals paid little attention to the police mistreatment of the women forced to spend time there, but as long as it was part of our nightly journies and in close proximity to our lives, this building and the institution it housed was available for political action. | ||

| − | |||

| + | Then in 1965, attention of a different kind was brought to the prison. Andrea Dworkin was arrested during an anti-Vietnam War protest, and like all the inmates, she was strip searched. But Dworkin refused to accept this lack of respect, and being a college student from an upper middle class family, she had the connections to make her outrage known. We read about her arrest and outrageous treatment in James Wechsler's column in the ''New York Post.''<ref>The ''New York Times'' also included a story that mentioned Dworkin's arrest and the protest about conditions as the prison: William E. Farrell, "Inquiry Ordered At Women's Jail: Mrs. Kross Acts in Case of a Bennington Student Seized in U.N. Protest," ''New York Times'', March 6, 1965. p.27.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| + | All of a sudden the prison and its world became an eyesore to the city, an embarrassment to the dapper Mayor John Lindsey, bad for real estate and tourism. As one journalist wrote, “from their stylish deco aerie, female inmates would regale passersby’s on busy 6th Avenue with obscene gestures and shouted curses. This obscenity was demolished in 1974.”<ref>Norval White and Elliot Willensky, eds., ''AIA Guide to New York City'', (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988).</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| + | The inmates were an insult to the structure. A shroud of shame fell over the prison, the street scenes, the inmates. The Women’s House of Detention disappeared from the heart of the Village, from our daily observation. | ||

| − | |||

| + | Sometime in the mid-1980s, I was unpacking a donated box of books at the Lesbian Herstory Archives and found a paperback expose of the prison, "Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women, " by Sara Harris (1967). Early in the first chapter, Dworkin lists the sight of lesbians as one of the outrages she endured: "Inside the cell blocks, homosexuality was increasingly aggressive. Girls were constantly making love with each other in front of the policewomen . . . ."<ref>Sara Harris, ''Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women'' (New York Dutton, 1967).</ref> | ||

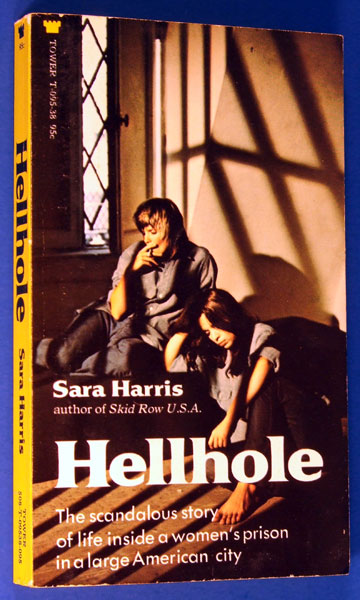

| − | + | [[Image:Hellhole011340.jpg|right|frame|First printing in mass market paperback, 1967.<ref>New York: Tower Publications Inc., 1967.</ref>]] | |

| − | The | + | Three years year ago, in ''The Guardian'' obituary about Dworkin, the reporter stated, as one of Dworkin’s feminist accomplishments, the closing of the women’s prison in Greenwich Village. As often happens, one class of women becomes invisible to make the world safer for another.<ref>Mark Honigsbuam, "Andrea Dworkin, embattled feminist dies at 58", ''The Guardian'', April 12, 2005. p.2.</ref> |

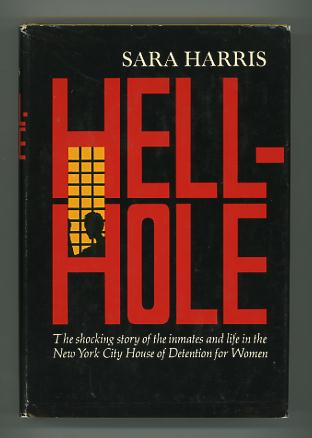

| + | [[Image:HarrisHELLHOLE14623.jpg|right|frame|First edition, 1967.<ref>Sara Harris. ''Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women''. New York E. P. Dutton & Co. , Inc. 1967. Illustrated by Anita Walker Scott.</ref>]] | ||

| − | + | In 1974,the building was torn down and replaced with a pretty garden, and the women’s prison was moved to an island in the middle of the Hudson River, where no one has to be reminded of its presence unless someone you know or love is imprisoned there. | |

| − | + | Because of my own queer historical roots, shame is an endlessly interesting source of ideas, not a memory from which to flee. Sites like the Women's House of D are prisms of shifting queer historical concerns; urbanity, what it will bear and what it will not, race and class divisions and connections--imprisonment both within jails and without. | |

| − | + | In terms of current thinking, the Women's House of Detention was not a site of assimilationism, but neither did it represent a romantic citadel of lesbian outlaw life. Economic despair, dispossession, state intrusion, racial oppression were the gritty realities of so many incarcerated within its 6th Avenue walls. | |

| − | + | As I walked into those dark hot nights of my youth, hungry for touch, I carried within me the voices of these separated lovers, their unrepentent shouts of need exposing them to judgement and the scorn of a city government. | |

| + | |||

| + | I am a strange kind of queer historian; my life's work has been driven by my pact with shame. I have done shameful acts in public and have sought out the richness of shameful lives. This is what interests me. I have seen whole communities betrayed by shame and seen others united by it. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As I have thought and written about queer history, about the years of surveillance, about what it took to walk the public streets as a queer in Joseph McCarthy’s America, I have always had a companion, the shamed body, and I have always learned from it—from its angers, its laughter, its sadness, its ecstasies, its moments of resistance and its communities—sometimes a prison, sometimes the Country Club. | |

| + | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | =Also see:= | |

| + | ==[[Nestle: Blog on History; Dexter and Diana: Voices in the Wind, 1950s-1990s]]== | ||

| + | ==[[Nestle: Blog on History; Thank You, Del Martin, 1921-2008]]== | ||

| + | ==[[Nestle: Blog on History; The Kiss, 1950s-1990s]]== | ||

| + | {{Protected}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Dworkin, Andrea (1946-2005)]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Lesbian]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Nestle, Joan (1940-)]] | |

| + | [[Category:Prison]] | ||

| + | [[Category:20th century]] | ||

| + | __NOTOC__ | ||

Latest revision as of 07:41, 2 September 2011

A City's Shame, A Community's Icon

by Joan Nestle. Copyright © Joan Nestle 2008. All rights reserved

(With this essay noted author and co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Joan Nestle inaugurates OutHistory's series of personal meditative blogs on LGBTQ and heterosexual history.)

The image of the fortress-like building that was the Women’s House of Detention (1931-1974) in Greenwich Village, New York City, has stayed with me all these many years. Fifty years before I read Foucalt, this building and its inhabitants declared to me the connections between deviance, punishment and unrepentent desire.

First, in the late 1950s and throughout the 60s when I was a young fem woman making my way late at night from my railroad apartment on 9th Street between Avenue A and Tompkins Park, walking across town on 8th Street, my destination the “Sea Colony,” a rough butch-fem bar across from Abington Square — east to west, my route went, and always past the dark medieval building that housed so many poor and working women, so many lesbians.

How to account for what stands solid through the years and changes of geographies, for what will become a basic structure of one’s historical memory?

The hot summer weekend nights that I stood and watched and listened to the pleas of lovers, butch women shouting up to the narrow-slitted windows, to hands waving handkerchiefs, to bodiless voices of love and despair, “Momi, the kids are okay,” marked me then and still do. Here, my sense of a New York lesbian history began, not a closeted one, but right there on the streets.

Tourists taking in the Village stopped and wondered at the spectacle of public women lovers in the midst of neotiating a hard patch in their lives, but neither stares or rude laughter interrupted this ritual of necessary and naked communication.

I stood those days, convinced I was a criminal too, on my way to my haven, a policed place where deviants were kept under a watchful eye, but given a small patch of freedom. From one urban street scene to another, my city was alive with freaks.

In the bar, with that subversive sense of humor that undercuts hardship, the Women’s House of D was called the “Country Club,” and friends were always asking after someone’s woman who was incarcerated. The prison was a presence in our lives—a warning, a beacon, a reminder and a moment of community.

Erected in 1931 on the bones of an older jail and market place, this urban prison reflected the changing penal philosophies of women's punishment that Estelle Freedman wrote so well of in Their Sister’s Keepers, beginning with a progressive plan for the betterment of the incarcerated women and then giving in to disdainful neglect as race and class chased out ideals.[2]

Dismissed as the prison for hookers, and other "obscenities," city officals paid little attention to the police mistreatment of the women forced to spend time there, but as long as it was part of our nightly journies and in close proximity to our lives, this building and the institution it housed was available for political action.

Then in 1965, attention of a different kind was brought to the prison. Andrea Dworkin was arrested during an anti-Vietnam War protest, and like all the inmates, she was strip searched. But Dworkin refused to accept this lack of respect, and being a college student from an upper middle class family, she had the connections to make her outrage known. We read about her arrest and outrageous treatment in James Wechsler's column in the New York Post.[3]

All of a sudden the prison and its world became an eyesore to the city, an embarrassment to the dapper Mayor John Lindsey, bad for real estate and tourism. As one journalist wrote, “from their stylish deco aerie, female inmates would regale passersby’s on busy 6th Avenue with obscene gestures and shouted curses. This obscenity was demolished in 1974.”[4]

The inmates were an insult to the structure. A shroud of shame fell over the prison, the street scenes, the inmates. The Women’s House of Detention disappeared from the heart of the Village, from our daily observation.

Sometime in the mid-1980s, I was unpacking a donated box of books at the Lesbian Herstory Archives and found a paperback expose of the prison, "Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women, " by Sara Harris (1967). Early in the first chapter, Dworkin lists the sight of lesbians as one of the outrages she endured: "Inside the cell blocks, homosexuality was increasingly aggressive. Girls were constantly making love with each other in front of the policewomen . . . ."[5]

Three years year ago, in The Guardian obituary about Dworkin, the reporter stated, as one of Dworkin’s feminist accomplishments, the closing of the women’s prison in Greenwich Village. As often happens, one class of women becomes invisible to make the world safer for another.[7]

In 1974,the building was torn down and replaced with a pretty garden, and the women’s prison was moved to an island in the middle of the Hudson River, where no one has to be reminded of its presence unless someone you know or love is imprisoned there.

Because of my own queer historical roots, shame is an endlessly interesting source of ideas, not a memory from which to flee. Sites like the Women's House of D are prisms of shifting queer historical concerns; urbanity, what it will bear and what it will not, race and class divisions and connections--imprisonment both within jails and without.

In terms of current thinking, the Women's House of Detention was not a site of assimilationism, but neither did it represent a romantic citadel of lesbian outlaw life. Economic despair, dispossession, state intrusion, racial oppression were the gritty realities of so many incarcerated within its 6th Avenue walls.

As I walked into those dark hot nights of my youth, hungry for touch, I carried within me the voices of these separated lovers, their unrepentent shouts of need exposing them to judgement and the scorn of a city government.

I am a strange kind of queer historian; my life's work has been driven by my pact with shame. I have done shameful acts in public and have sought out the richness of shameful lives. This is what interests me. I have seen whole communities betrayed by shame and seen others united by it.

As I have thought and written about queer history, about the years of surveillance, about what it took to walk the public streets as a queer in Joseph McCarthy’s America, I have always had a companion, the shamed body, and I have always learned from it—from its angers, its laughter, its sadness, its ecstasies, its moments of resistance and its communities—sometimes a prison, sometimes the Country Club.

Also see:

Nestle: Blog on History; Dexter and Diana: Voices in the Wind, 1950s-1990s

Nestle: Blog on History; Thank You, Del Martin, 1921-2008

Nestle: Blog on History; The Kiss, 1950s-1990s

References

- ↑ http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GV/GV028JeffersonMarketLibrary.htm

- ↑ Estelle B. Freedman, Their Sisters' Keepers: Women's Prison Reform in America, 1830-1930 (University of Michigan Press, 1981).

- ↑ The New York Times also included a story that mentioned Dworkin's arrest and the protest about conditions as the prison: William E. Farrell, "Inquiry Ordered At Women's Jail: Mrs. Kross Acts in Case of a Bennington Student Seized in U.N. Protest," New York Times, March 6, 1965. p.27.

- ↑ Norval White and Elliot Willensky, eds., AIA Guide to New York City, (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988).

- ↑ Sara Harris, Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women (New York Dutton, 1967).

- ↑ New York: Tower Publications Inc., 1967.

- ↑ Mark Honigsbuam, "Andrea Dworkin, embattled feminist dies at 58", The Guardian, April 12, 2005. p.2.

- ↑ Sara Harris. Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women. New York E. P. Dutton & Co. , Inc. 1967. Illustrated by Anita Walker Scott.