Difference between revisions of "Stonewall Park"

m |

m |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==Living Freely & Simply == | ==Living Freely & Simply == | ||

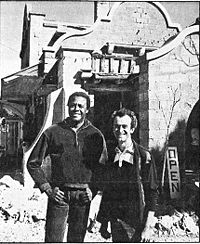

| − | [[Image:fred_alfred1970s.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Fred Schoonmaker and Alfred Parkinson, 1970s]]In 1983, Reno gay activist Fred Schoonmaker and his husband, Alfred Parkinson, conceived a series of efforts to establish a gay town in Nevada known as Stonewall Park, named for the 1969 New York riots that marked the beginning of the fight for gay equality. Social and legal discrimination against gay people in Nevada had reached such a pitch by the early 1980s that many in the state believed the only way they could survive was to segregate themselves from the straight population. Schoonmaker, in particular, felt his repression acutely, having grown up in West Virginia and lost two gay friends to suicide when he was a teenager.<ref name="ref1">For the full story of Stonewall Park, see Dennis McBride, “Stonewall Park,” ''Nevada Historical Society Quarterly'', v. 52:2 [Summer 2009]; ''Advocate'' (October 14, 1986), pp. 10-11, 20; ''Los Angeles Times'' (February 15, 1987), part 6, pp. 1, 8;</ref> | + | [[Image:fred_alfred1970s.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Fred Schoonmaker(l) and Alfred Parkinson(r), 1970s]]In 1983, Reno gay activist Fred Schoonmaker and his husband, Alfred Parkinson, conceived a series of efforts to establish a gay town in Nevada known as Stonewall Park, named for the 1969 New York riots that marked the beginning of the fight for gay equality. Social and legal discrimination against gay people in Nevada had reached such a pitch by the early 1980s that many in the state believed the only way they could survive was to segregate themselves from the straight population. Schoonmaker, in particular, felt his repression acutely, having grown up in West Virginia and lost two gay friends to suicide when he was a teenager.<ref name="ref1">For the full story of Stonewall Park, see Dennis McBride, “Stonewall Park,” ''Nevada Historical Society Quarterly'', v. 52:2 [Summer 2009]; ''Advocate'' (October 14, 1986), pp. 10-11, 20; ''Los Angeles Times'' (February 15, 1987), part 6, pp. 1, 8;</ref> |

[[Image: stockcert1984.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Stonewall Park stock certificate, 1984]]A segregated community for gay people was not a new idea. Schoonmaker likely had been aware of, perhaps even involved with, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front's [GLF-LA] Alpine County project in northern California. In the summer of 1970 the GLF-LA announced it was moving 479 gay people into northern California's tiny Alpine County where they would take over the town and establish a gay community with "a gay government, a gay civil service [and] the world's first museum of gay arts, sciences, and history, paid for with public funds." The proposal shocked California's government and brought a lot of publicity to the GLF-LA. Whether the Alpine County venture was serious or a publicity stunt was never clear, but it would have been an endeavor Fred Schoonmaker would gladly have joined.<ref name="ref2">Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons, ''Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians'' (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2006), 177-79.</ref> | [[Image: stockcert1984.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Stonewall Park stock certificate, 1984]]A segregated community for gay people was not a new idea. Schoonmaker likely had been aware of, perhaps even involved with, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front's [GLF-LA] Alpine County project in northern California. In the summer of 1970 the GLF-LA announced it was moving 479 gay people into northern California's tiny Alpine County where they would take over the town and establish a gay community with "a gay government, a gay civil service [and] the world's first museum of gay arts, sciences, and history, paid for with public funds." The proposal shocked California's government and brought a lot of publicity to the GLF-LA. Whether the Alpine County venture was serious or a publicity stunt was never clear, but it would have been an endeavor Fred Schoonmaker would gladly have joined.<ref name="ref2">Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons, ''Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians'' (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2006), 177-79.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:03, 19 February 2010

Stonewall Park

(c)Dennis McBride, 2009

Living Freely & Simply

In 1983, Reno gay activist Fred Schoonmaker and his husband, Alfred Parkinson, conceived a series of efforts to establish a gay town in Nevada known as Stonewall Park, named for the 1969 New York riots that marked the beginning of the fight for gay equality. Social and legal discrimination against gay people in Nevada had reached such a pitch by the early 1980s that many in the state believed the only way they could survive was to segregate themselves from the straight population. Schoonmaker, in particular, felt his repression acutely, having grown up in West Virginia and lost two gay friends to suicide when he was a teenager.[1]

A segregated community for gay people was not a new idea. Schoonmaker likely had been aware of, perhaps even involved with, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front's [GLF-LA] Alpine County project in northern California. In the summer of 1970 the GLF-LA announced it was moving 479 gay people into northern California's tiny Alpine County where they would take over the town and establish a gay community with "a gay government, a gay civil service [and] the world's first museum of gay arts, sciences, and history, paid for with public funds." The proposal shocked California's government and brought a lot of publicity to the GLF-LA. Whether the Alpine County venture was serious or a publicity stunt was never clear, but it would have been an endeavor Fred Schoonmaker would gladly have joined.[2]

Schoonmaker first announced his intentions in 1984, when he told the Reno Gazette-Journal that he dreamed of establishing a gay town complete with “a casino, tennis courts, spas, condominiums, and single-family homes.” He also admitted that the settlement would have to be built outside Washoe County because he didn’t believe the county commission’s “pro-growth attitude” would outweigh its “anti-gay attitude.” Schoonmaker claimed his idea for Stonewall Park came from a comment his husband, Alfred, made one summer when they were discussing the difficulty of their life in Reno as an interracial gay couple—Fred was white, Alfred was African-American. Schoonmaker yearned for a place where they could live freely and simply as who they were. Parkinson said, "Well, if you're ever going to find a place like that, you're going to have to build it yourself." Schoonmaker said his obsession was born at that moment. In private conversations, however, Fred admitted he wanted to establish a segregated gay community for Alfred who, Schoonmaker felt, "needed … a safe and peaceful place" to live after Fred was gone, since he expected Alfred to outlive him.[3]

Choosing a Location

Silver Springs, Nevada

The first place Schoonmaker chose as a likely site for Stonewall Park was the small desert town of Silver Springs, Nevada, on Highway 50 midway between Carson City and Fallon. To promote the venture, Fred established Reno’s first gay magazine, Stonewall Voice, and enlisted the help of several people from the Reno gay community. Schoonmaker also partnered with Robert and Margaret Askew, a straight couple who purportedly ran a marketing business called Venture Marketing Services.[4]

When the project was presented, however, the citizens in Silver Springs and surrounding area squarely opposed it. As Janine Hansen of the anti-gay Pro-Family Christian Coalition in Reno wrote, "I can't believe that under these circumstances with regard to AIDS that someone is trying to bring this into our community. ... [B]ringing the homosexual 'death style' to Reno would be a blight on our community." Others, responding to mailings Schoonmaker sent across the country, felt quite differently. Christopher McCrary of Columbia, Missouri, wrote that he and his partner were eager "to become a member of the planned residential community, for my lover and I ... have witnessed bigotry, hatred, fear, and prejudice at its worst.” Stonewall Park Silver Springs failed to make it through the Lyon County Planning Commission, and this first venture deteriorated into a storm of homophobia not only from residents of Silver Springs, but from Schoonmaker’s partners, Bob and Margaret Askew. The Askews separated themselves from the project, and sued Schoonmaker, claiming they never realized Stonewall Park was meant to be gay. In turn, Schoonmaker sued the Askews. A parting shot was made by Silver Springs resident Kathy Morser, who expressed her fear that gay people would “take over the area ... .We're frustrated with all the federal laws on homosexuals. They have all these rights and we don't have any."[5]

Rhyolite, Nevada

Driven from Silver Springs—but determined not to give up--Fred, Alfred, and their supporters moved on to Rhyolite, Nevada, the famous ghost town just west of Beatty in Nevada’s Nye County. The media circus that followed made the project international news.[6]

The City of Rhyolite, Inc. was owned in part by Jim Spencer, a former editor of Arizona’s Tombstone Epitaph, who had been trying since 1983 to restore Rhyolite to its former glory. Rhyolite was the site of the annual Bullfrog Endurance and Fun Run event, named for the famed Bullfrog Mining District. In 1984, renowned Belgian sculptor Albert Szukalski lived in Rhyolite and produced a ghostly set of fiberglass figures representing the Last Supper, which overlooked the rotting buildings and blowing sand. It was failure to attract enough investors into his restoration scheme that moved Spencer to sell Rhyolite to Schoonmaker when mutual friend Rob Schlegel, publisher of Las Vegas’s gay magazine, the Bohemian Bugle, brought them together. As an incorporated city, Rhyolite could be operated autonomously of state or county law and, theoretically, could decriminalize homosexuality within its borders. And because Las Vegas was not far away with its much larger and more active gay community, Schoonmaker felt he could count on that support. Fred and Alfred moved from Reno to Rhyolite and took up residence in an old caboose near the Rhyolite train depot.[7]

But Stonewall Rhyolite failed, as well. The intense media attention the project invited brought out the worst in Beatty’s citizens and Nye County officials. Nye County Commissioner Bob Revert, for instance, said, "We're not San Francisco. A bunch of damn queers want to build a town of their own and I don't like it one bit. As long as I'm county commissioner it will never materialize. I'm very embarrassed and I'll do everything I can to prevent it.” and, "This is redneck country. When they get to the Nye County line, they cease being gays. They turn into queers." Beatty school children were overheard referring to Rhyolite as "Gayolite," and "Fagolite. Worse, snipers drove out to Rhyolite from Beatty to shoot the windows out of Fred’s and Alfred’s caboose, shouting “faggot” and “nigger.” Stonewall Rhyolite also never got the wide-spread support from Las Vegas or from around the country that Schoonmaker expected. Finally, Schoonmaker simply did not have the money to make his first down payment on Rhyolite. Disappointed and terrified, Fred and Alfred returned to Reno.[8]

Thunder Mountain, Nevada

Schoonmaker tried one more time. Even before the Rhyolite venture was dead, Fred was working another deal with friend Stormy Caldwell, who owned a forty-acre ranch in Pershing County between Lovelock and Winnemucca. Looming over this desolate and waterless landscape was the dark peak of Thunder Mountain. Schoonmaker inherited money when his mother died and he bought the Thunder Mountain property for Stonewall Park.[9]

As soon as the news broke, opposition to Stonewall Park arose, as though the presence of gay people in one of Nevada's most desolate and depressed areas would make conditions worse. More than 200 Pershing County residents signed a petition opposing Stonewall Park. District Attorney Richard Wagner was discouraging in his comments about water and zoning. Governor Richard Bryan felt most Nevadans wanted to see Stonewall Park built in another state. Republican Assemblyman John Marvel from Battle Mountain compared gay people to the cattle in his stockyards: "Since I raise animals, I'm very gender-conscious. If I have a bull that doesn't know the difference between genders, he goes down the road.” That was the end of Stonewall Park Thunder Mountain.[10]

Death of Fred Schnoomaker

The death of his dream many believe hastened the death of Fred Schoonmaker. Schoonmaker had been ill with AIDS for some time, although he was not diagnosed until March 23, 1987. In the depths of his illness, Fred and Alfred were living in a dingy apartment on Carlin Street in Reno, unemployed and destitute, fed by friends who had stayed with them through the Stonewall ventures. Fred became bedridden, then comatose, and on May 20, 1987, died of an AIDS-related heart attack. Alfred, also infected, and carrying his husband’s ashes, returned to the Bay Area where he’d first met Fred.[11]

While many felt Fred had wasted the last years of his life on an impossible pursuit, Rod Sumpter and Stormy Caldwell were not among them.

"The idea of Stonewall should live on in all of us," Caldwell said. "Maybe it was a lost cause, but it was a good dream."

"The idea about a segregated community was a little far-out," Sumpter said, "[but] Fred was trying to live without being persecuted in a state where sodomy was still outlawed. Every little thing like [the Stonewall ventures] that got publicity, good or bad, let people know that gay people were there and we want to be treated [fairly and equally], and we'll go so far as to have our own [town] someplace in order to live and be the people we wanna be. This was how far somebody really felt they had to go to be comfortable in that day and age. That's very insightful, I think."

- ↑ For the full story of Stonewall Park, see Dennis McBride, “Stonewall Park,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, v. 52:2 [Summer 2009]; Advocate (October 14, 1986), pp. 10-11, 20; Los Angeles Times (February 15, 1987), part 6, pp. 1, 8;

- ↑ Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons, Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2006), 177-79.

- ↑ Reno Gazette-Journal (November 19, 1984), pp. 1B, 4B; Theodore “Ted” Tucker, letters to the author, 7 May and 1 August 2004 [University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Lied Library, Special Collections Department (hereafter noted as UNLS), MS 2005-06 (Stonewall Park)]; Marguerita "Stormy" Caldwell, interview by Dennis McBride, 26 March 2005 [author’s transcript]; Rodney Sumpter, interview by Dennis McBride, 20 January 2004 [author’s transcript].

- ↑ Stonewall Voice was known first as Gay Life Reno and Gay Life Nevada (September - November 1984), Gay Life (December 1984 - July 1985), and, by August 1985, as Stonewall Voice; Second Judicial Court, Washoe County, Nevada case no. 86-3810 (May 2, 1986 [UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park]); US Bankruptcy Court case no. 85-787 (UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park); Caldwell interview; Sumpter interview; Pamela Dallas, interview by Dennis McBride, 7 February 2004 [author’s transcript]; Roy Baker, interview by Dennis McBride, 8 February 2004 [author’s transcript]; [San Francisco, CA] Museum of GLBT History (hereafter noted as GLBT), MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers); Gay Life Reno (September 1984), all; Gay Life Nevada (November 11, 1984), p. 18; Reno Gazette-Journal (November 19, 1984), pp. 1B, 4B; Gay Life (January 1985), pp. 9, 12; (April 1985), pp. 1, 8; (June 1985), p. 5; (July 1985), p. 12; Stonewall Voice (August 1985), all; Washington Blade June 6, 1986), p. 9; Tucker, letter to the author, 7 May, 2004.

- ↑ Reno Gazette-Journal (December 20, 1985), pp. 1C, 6C; (April 20, 1986), pp. 1C-2C; (April 25, 1986), p. 2C; (May 20, 1986), pp. 1C-2C; (May 21, 1986), pp. 1C-2C; (May 30, 1986), p. 2C; (June 22, 1986), p. 6D; UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park; Mason Valley News (April 11, 1986), pp. 1, 6; (April 18, 1986), pp. 1, 3; (April 25, 1986), pp. 1, 8; (May 2, 1986), pp. 1, 7; (May 9, 1986), pp. 1, 8; (May 16, 1986), section 1, p. 2; (May 23, 1986), pp. 1-2; (May 30, 1986), p. 1; (June 13, 1986), pp. 1, 8; (June 27, 1986), pp. 1, 8; Fernley Leader-Courier (April 16, 1986), pp. 1, 8; (April 23, 1986), pp. 1, 8; (April 30, 1986), p. 1; (May 7, 1986), p. 1; (May 14, 1986, p. 1); (May 28, 1986), pp. 1, 4; (June 13, 1986), pp. 1-3; (June 25, 1986), p. 1; Advocate (October 14, 1986), pp. 10-11; Pamela Dallas, letter to the author, 11 April, 2004 (UNLS MS 2004-06); Second Judicial District Court of Washoe County case no. 86-3810 (UNLS MS 2004-06); Dallas interview; Sumpter interview; US Bankruptcy Court, District of Northern California, case no. 83-00523, March 9, 1983, and US Bankruptcy Court, District of Nevada, 85-1169, August 13, 1985, (UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park); GLBT MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers)

- ↑ Bohemian Bugle (October 1986), pp. 1, 11, 14; Death Valley Gateway Gazette (October 10, 1986), pp. 1, 3, 6; (October 17, 1986), pp. 1, 18; (October 31, 1986), pp. 1, 11; (November 7, 1986), p. 2; (November 21, 1986), p. 2; Las Vegas Review-Journal (November 3, 1986), pp. 1A, 3A; (June 15, 1987), p. 1B; UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park; Advocate (October 14, 1986), pp. 10-11, 20; Robert “Rob” Schlegel, interview by Dennis McBride, 9-11 and 21-22 March and 11 April 1998 [author’s transcript]; Caldwell interview; Sumpter interview; Dallas interview; Baker interview; GLBT MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers).

- ↑ Reno Gazette-Journal (February 5, 1984), p. 2C; (July 9, 1985), p. 2C; (July 10, 1985), p. 13A; (October 10, 1986), pp. 1C-2C; (November 1, 1986), p. 1C; (November 4, 1986), p. 1C; (November 9, 1986), pp. 1D, 3D; Las Vegas Review-Journal (October 9, 1986), p. 1B; (November 3, 1986), pp. 1A, 3A; (January 11, 1987), pp. 1B, 3B; San Francisco Chronicle (October 10, 1986), pp. 1, 24; Death Valley Gateway Gazette (October 10, 1986), pp. 1, 3, 6; (December 5, 1986), pp. 1, 12; Las Vegas Sun (October 10, 1986), p. 4B; Sacramento Bee (October 19, 1986), pp. A1, A28; Bohemian Bugle (October 1986), pp. 1, 11, 14; (November 1986), pp. 1, 8, 10, 12; (December 1986), pp. 1, 14; Washington Post (December 9, 1986), pp. C1, C4; Advocate (December 23, 1986), pp. 15-16; (January 20, 1987), pp. 14-15; Fred Schoonmaker, letter to “Ann,” 16 January 1987 (UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park); Caldwell interview; Sumpter interview; Baker interview; Schlegel interview; GLBT MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers).

- ↑ Death Valley Gateway Gazette (October 10, 1986), pp. 1, 3; (October 24, 1986), p. 8; (November 21, 1986), p. 2; (December 5, 1986), pp. 1, 2, 12; (December 19, 1986), p. 2; Las Vegas Review-Journal (October 9, 1986), pp. 1B, 3B; (October 19, 1986), p. 3CC; (December 17, 1986), p. 7B; (January 11, 1987), pp. 1B, 3B; Reno Gazette-Journal (November 9, 1986), pp. 1D, 3D; (December 17, 1986), pp. 1C-2C; Las Vegas Sun (October 10, 1986), p. 4B; San Francisco Chronicle (October 10, 1986), pp. 1, 24; Sacramento Bee (October 10, 1986), pp. A1, A28; Washington Post (December 9, 1986), p. C1, C4; Weekly World News (November 25, 1986); [Cincinnati, OH] Gaybeat (February 1987), pp. 1, 6; Los Angeles Times (February 15, 1987), section 6, pp. 1, 8; Gay Life (January 1985), p. 5; Bohemian Bugle (November 1986), p. 10; Advocate (December 23, 1986), pp. 15-16; (January 20, 1987), pp. 14-15; Caldwell interview; Sumpter interview; Dallas interview; Baker interview; Schlegel interview; UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park; GLBT MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers).

- ↑ Real Estate Contract of Sale between Marguerita Arthe Marin Caldwell and Fred Schoonmaker, December 16, 1986, and Quitclaim Deeds no. 151623 and 151624, Pershing County, Nevada, December 17, 1986 (UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park); GLBT MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers).

- ↑ Reno Gazette-Journal (December 17, 1986), pp. 1C-2C; (January 8, 1987), p. 3C; (January 11, 1987), pp. 1B, 3B; (February 17, 1987), pp. 1C-2C; Las Vegas Sun (December 18, 1986), p. 2A; Los Angeles Times (February 15, 1987), section 6, pp. 1, 8; Death Valley Gateway Gazette (December 19, 1986), p. 2; Advocate (February 17, 1987), p. 26; [Cincinnati, OH] Gaybeat (February 1987), pp. 1, 6; Bohemian Bugle (June 1987), p. 22; Las Vegas Review-Journal (January 11, 1987), pp. 1B, 3B; (June 15, 1987), p. 1B; Lovelock [Nevada] Tribune (December 18, 1986), pp. 1, 12; [Kansas City, MO] Alternate News (March 6, 1987), pp. 4, 32; UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park; GLBT MS 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers).

- ↑ UNLS MS 2004-06: Stonewall Park; GLBT 1990-15 (Fred Schoonmaker Papers); Bohemian Bugle (June 1987), p. 22; Las Vegas Review-Journal (June 15, 1987), p. 1B; Schlegel interview; Caldwell interview; Baker interview; Sumpter interview.