Difference between revisions of "Twin Cities Pride Parade"

(table +table) |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

The march transformed into a parade sometime in the 1980s, when the HIV/AIDS pandemic inspired changing strategies for greater acceptance. In the late 80s, the Twin Cities Pride Committee made a grave mistake that almost spelled the parade’s doom. | The march transformed into a parade sometime in the 1980s, when the HIV/AIDS pandemic inspired changing strategies for greater acceptance. In the late 80s, the Twin Cities Pride Committee made a grave mistake that almost spelled the parade’s doom. | ||

| − | | [[Image:Svc 2nd pride.jpg]] | + | | <div style="text-align: center;"> |

| + | [[Image:Svc 2nd pride.jpg]] | ||

| + | </div> <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | <small>'''The second Twin Cities Pride March on the Nicollet Mall, 1973. Courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

In 1987, the Committee chose a route away from Loring Park that stretched from Lake Calhoun to Powderhorn Park along 32nd street. The 2-mile path exhausted participants, bored attendees, and threatened to event’s future. Some even referred to that year's parade as "the death march." | In 1987, the Committee chose a route away from Loring Park that stretched from Lake Calhoun to Powderhorn Park along 32nd street. The 2-mile path exhausted participants, bored attendees, and threatened to event’s future. Some even referred to that year's parade as "the death march." | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| {{prettytable}} | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

! | ! | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Hope came in the form of a transgender woman with a penchant for military fashion. Ashley Rukes, who directed the Aquatennial Parade in 1975, first volunteered her expertise in 1992. Rukes initiated communication with Minneapolis Police, established a pioneering lineup system for the parade’s many contingents, and encouraged even the smallest groups to participate. | + | | <div style="text-align: center;"> |

| + | [[Image:Picture_3.png]] | ||

| + | </div> <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | <small>'''Ashley Rukes on the cover of Gaze Magazine, 1993. Courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |Hope came in the form of a transgender woman with a penchant for military fashion. Ashley Rukes, who directed the Aquatennial Parade in 1975, first volunteered her expertise in 1992. Rukes initiated communication with Minneapolis Police, established a pioneering lineup system for the parade’s many contingents, and encouraged even the smallest groups to participate. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 40: | ||

| − | Shock and sadness met the Director’s untimely death shortly before pride weekend in 1999. The Pride Committee now names the parade in her honor. | + | Shock and sadness met the Director’s untimely death shortly before pride weekend in 1999. The Pride Committee now names the parade in her honor.<div style="text-align: center;"> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 22:21, 27 February 2010

Nicollet Avenue, Marquette Avenue, 24th Street W., Lyndale Avenue, and 32nd Street by various routes, (1972-2010)

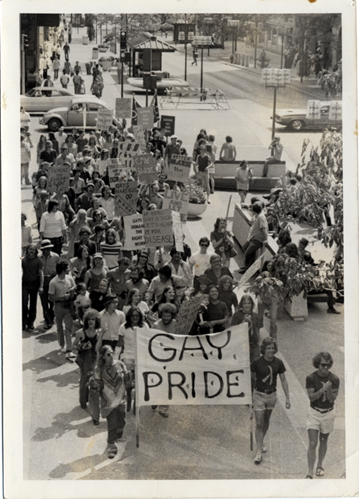

| The Twin Cities Pride Parade began as a 50-strong protest march on the (newly-built) Nicollet Mall in 1972. Downtown shoppers and office workers composed a majority of the event's few spectators, and of these, few had “the foggiest idea what [the marchers] were talking about.” Americans were still fighting in the Vietnam War, and this produced countless protest marches. Gay Pride appeared to be just another slogan on hand-painted pickets; the concept garnered little attention.

|

The second Twin Cities Pride March on the Nicollet Mall, 1973. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

In 1987, the Committee chose a route away from Loring Park that stretched from Lake Calhoun to Powderhorn Park along 32nd street. The 2-mile path exhausted participants, bored attendees, and threatened to event’s future. Some even referred to that year's parade as "the death march."

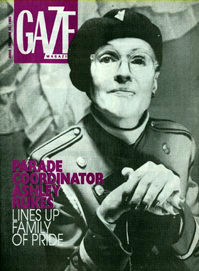

| Ashley Rukes on the cover of Gaze Magazine, 1993. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

Hope came in the form of a transgender woman with a penchant for military fashion. Ashley Rukes, who directed the Aquatennial Parade in 1975, first volunteered her expertise in 1992. Rukes initiated communication with Minneapolis Police, established a pioneering lineup system for the parade’s many contingents, and encouraged even the smallest groups to participate.

|

This page is still under contruction. --SVC

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)