Difference between revisions of "The Dugout Bar"

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |The Dugout was unlike any other bar at the time, as it served an almost exclusively queer clientele in downtown Minneapolis. It was a popular hangout for veterans of the Second World War.<small>(1)</small> | + | |The Dugout was unlike any other bar at the time, as it served an almost exclusively queer clientele in downtown Minneapolis, on the border of the old [[Gateway District]]. It was a popular hangout for veterans of the Second World War, who maintained a clandestine community after returning home.<small>(1)</small> |

| − | As its name implied, the bar's masculine patrons were more apt to discuss baseball statistics than topics that related to their sexual preferences. Queer women possibly joined men at the Dugout, but their participation was socially and legally restricted. | + | As its name implied, the bar's working-class and masculine patrons were more apt to discuss baseball statistics than topics that related to their sexual preferences. Sexually explicit men, effeminate men, and the upper-class frequented the Viking Room in the old Hotel Radisson on 7th Street.<small>(2)</small> Queer women possibly joined men at the Dugout, but their participation was socially and legally restricted. |

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| − | + | The Dugout sat in the seedy backwaters of the old [[Gateway District]]—Minneapolis’ longtime locus of various criminal activity, including prostitution.<small>(3)</small> An anti-prostitution law (ironically) prevented women from entering bars without a male escort, thus lesbian couples were forbidden from using bars as sites of socialization.<small>(4)</small> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The Dugout sat in the seedy backwaters of the old [[Gateway District]]—Minneapolis’ longtime locus of prostitution. An anti-prostitution law (ironically) prevented women from entering bars without a male escort, thus lesbian couples were forbidden from using bars as sites of socialization.<small>( | ||

| Line 37: | Line 34: | ||

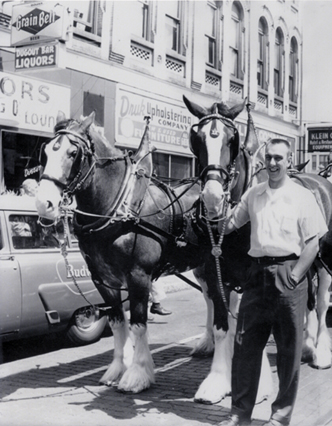

<small>'''Exterior photo of the Dugout and the bar's owner on Third Street South. Photo dontated by Mark A. Morrill, courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | <small>'''Exterior photo of the Dugout and the bar's owner on Third Street South. Photo dontated by Mark A. Morrill, courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | | Of course, this was not always the Gateway’s case. 50 years before, the Dugout’s building was part of Minneapolis’ epicenter. Its site was part of old Harmonia Hall, a largely-forgotten 19th century auditorium for the city’s large German population.<small>( | + | | Of course, this was not always the Gateway’s case. 50 years before, the Dugout’s building was part of Minneapolis’ epicenter. Its site was part of old Harmonia Hall, a largely-forgotten 19th century auditorium for the city’s large German population.<small>(5)</small> |

| Line 43: | Line 40: | ||

| − | Other nearby bars—including the Trocadero (at 251 2nd Av S.) and the Persian Palms (at 109-111 Washington Ave S.)— catered to queer clientele as well, but they also catered to transient drunks, criminals, and “slummers” on the prowl for a wild time.<small>( | + | Other nearby bars—including the Trocadero (at 251 2nd Av S.) and the Persian Palms (at 109-111 Washington Ave S.)— catered to queer clientele as well, but they also catered to transient drunks, criminals, and “slummers” on the prowl for a wild time.<small>(6)</small> Queer men often fell victim to the last group, as the victims feared outing and rarely reported robberies or beatings to the police. |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 56: | Line 53: | ||

<small>(2)</small>Brown, Ricardo J. The Evening Crowd at Kirmer's: A Gay Life in the 1940s. Minneapolis: University of Minnesita Press, 2001. Pages 6-7. | <small>(2)</small>Brown, Ricardo J. The Evening Crowd at Kirmer's: A Gay Life in the 1940s. Minneapolis: University of Minnesita Press, 2001. Pages 6-7. | ||

| − | <small>(3)</small>Enke, Anne. Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2007. Page 40. | + | <small>(3)</small>According to a survey of Minneapolis "Berlillion Books--a record of every criminal who entered into police custody--between 1916 and 1918. The books are available in the Records Division of the Minneapolis City Clerk's office, within the [[Old Minneapolis Courthouse/City Hall]]. |

| + | |||

| + | <small>(4)</small>Enke, Anne. Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2007. Page 40. | ||

| − | <small>( | + | <small>(5)</small>Based on a comparison of the photographs on this page with photographs of Harmonia Hall: http://collections.mnhs.org/visualresources/Results.cfm?Page=1&Keywords=harmonia%20hall&SearchType=Basic&CFID=16026573&CFTOKEN=40085628] |

| − | <small>( | + | <small>(6)</small>Rosheim, David L. ''The Other Minneapolis, or The Rise and Fall of the Old Gateway, Minneapolis' Skid Row''. Minneapolis: Andromeda Press, 1978. |

Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | ||

Revision as of 22:58, 14 March 2010

206 Third Street South, Minneapolis (1940? – 1959)

| The Dugout was unlike any other bar at the time, as it served an almost exclusively queer clientele in downtown Minneapolis, on the border of the old Gateway District. It was a popular hangout for veterans of the Second World War, who maintained a clandestine community after returning home.(1)

As its name implied, the bar's working-class and masculine patrons were more apt to discuss baseball statistics than topics that related to their sexual preferences. Sexually explicit men, effeminate men, and the upper-class frequented the Viking Room in the old Hotel Radisson on 7th Street.(2) Queer women possibly joined men at the Dugout, but their participation was socially and legally restricted.

|

Interior photo of the Dugout shortly before demolition. Image donated by Mark A. Morrill, the owner's grandson. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

The Dugout sat in the seedy backwaters of the old Gateway District—Minneapolis’ longtime locus of various criminal activity, including prostitution.(3) An anti-prostitution law (ironically) prevented women from entering bars without a male escort, thus lesbian couples were forbidden from using bars as sites of socialization.(4)

Exterior photo of the Dugout and the bar's owner on Third Street South. Photo dontated by Mark A. Morrill, courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

Of course, this was not always the Gateway’s case. 50 years before, the Dugout’s building was part of Minneapolis’ epicenter. Its site was part of old Harmonia Hall, a largely-forgotten 19th century auditorium for the city’s large German population.(5)

|

The Dugout was part of the roundly-criticized Gateway Urban Renewal Project. The city of Minneapolis cleared the entire block and it remained a parking lot for 19 years. 255 Avenue South—an office block—occupies the site, and it is part of the Wells Fargo Campus.

(1)Tretter, Jean-Nickolaus. Interview with the author, 10/25/09.

(2)Brown, Ricardo J. The Evening Crowd at Kirmer's: A Gay Life in the 1940s. Minneapolis: University of Minnesita Press, 2001. Pages 6-7.

(3)According to a survey of Minneapolis "Berlillion Books--a record of every criminal who entered into police custody--between 1916 and 1918. The books are available in the Records Division of the Minneapolis City Clerk's office, within the Old Minneapolis Courthouse/City Hall.

(4)Enke, Anne. Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2007. Page 40.

(5)Based on a comparison of the photographs on this page with photographs of Harmonia Hall: http://collections.mnhs.org/visualresources/Results.cfm?Page=1&Keywords=harmonia%20hall&SearchType=Basic&CFID=16026573&CFTOKEN=40085628]

(6)Rosheim, David L. The Other Minneapolis, or The Rise and Fall of the Old Gateway, Minneapolis' Skid Row. Minneapolis: Andromeda Press, 1978.

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)