Difference between revisions of "3: Questions for Viewers"

From OutHistory

Jump to navigationJump to search| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | <div align='right'>'''Continued from:''' [[2: The Man-Monster Lithograph]]</div> | + | ENTRY UNDER CONSTRUCTION |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''<div align='right'>'''Continued from:''' [[2: The Man-Monster Lithograph]]</div> | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

=Ten Questions for Viewers of The Man-Monster Exhibit= | =Ten Questions for Viewers of The Man-Monster Exhibit= | ||

Revision as of 21:22, 1 July 2011

ENTRY UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Continued from: 2: The Man-Monster Lithograph

Ten Questions for Viewers of The Man-Monster Exhibit

- The goal of these questions is to help viewers locate the Man-Monster print in context of its time. Please leave your responses in the Comment box at the bottom of the page.

(1) How does the Man-Monster print visually characterize a black woman?

(2) Does the characterization "Man-Monster" contradict the visualization of Sewally/Jones in the print?

(3) How does this print's representation of a black woman compare with other images of black women in American popular culture of the 19th century?

- Consider images from print culture, sentimental fiction, and the minstrel stage. Here are two examples:

Below: Minstrel show performers Rollin Howard (in wench costume) and George Griffin, c. 1855.[1]

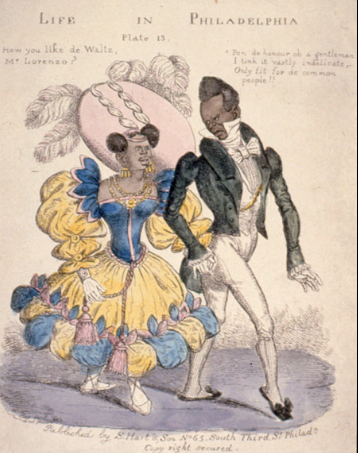

Below: From E.W. Clay, Life in Philadelphia," 1829.[2]

(4) How expensive was the Man-Monster print, and what class of people would be expected to buy it?

- You probably don't know the answer, but take a guess. Or look for evidence on the Internet.

(5) What might a buyer of the Man-Monster print like about it?

(6) What does the history of the Man-Monster print's maker and publisher tell us about the character of his print

- See our earlier entry about the publisher at: 2: The Man-Monster Lithograph

(7) How might we think about the Man-Monster print in relation to the sexually suggestive Helen Jewett print produced by the same printer?

- See 2: The Man-Monster Lithograph. By the way, none of this printer's pornographic prints are known to exist.

(8) How might the Man-Monster print relate to 19th century men’s interest in and anxiety about independent women, female sex workers, and sapphic desire?

(9) Does the Man-Monster image provide insight into the history of transgendered bodies and identities?

(10) Can you think of other questions that can help us understand this image in its original historical context?

- If so, we'd all love to hear them. Please leave your answers, thoughts, and comments in the Comment box below.

Next: 4: The Man-Monster's Legacy

Notes

- ↑ Scan from: William J. Mahar. Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture. University of Illinois Press December 1, 1998. ISBN-10: 9780252066962. ISBN-13: 978-0252066962. ASIN: 0252066960.

- ↑ E. W. Clay began drawing a very popular series of cartoons in 1828, after he had seen George and Robert Cruikshank's Life in London drawings while on a trip to England. Their work featured the adventures of three uninhibited young men on the town; Clay's focused on social pretensions. Between 1828 and 1830 he produced 14 aquatint engravings for the series: 4 depicted whites; 10 were caricatures of Philadelphia's free black population. The drawings were extremely popular; they were reproduced in a number of media, in more and less expensive forms, and were widely imitated by cartoonists in other cities, including New York and London. The comic image of the hyper-elegant urban black would soon become one of the two essential stereotypes of the minstrel stage. E.W. Clay, "Life in Philadelphia" Series. Philadelphia: published variously by Wm. Simpson and S. Hart, 1828-1830. Information accessed July 1, 2011 from University of Virginia website at: http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/abolitn/gallclayf.html