Difference between revisions of "Nightlife and Entertainment"

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

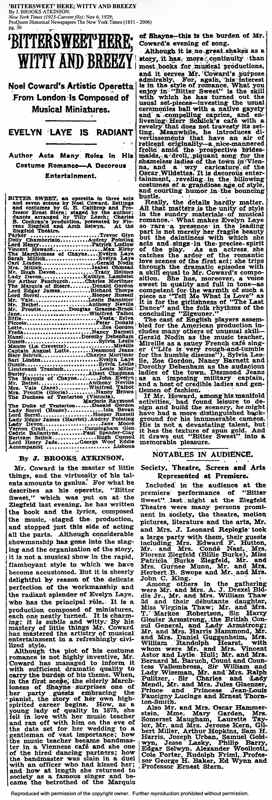

[[Image:Atkinson_Bitter_Sweet_Review.jpg|thumb|Brooks Atkinson, 'Bittersweet' Here; Witty and Breezy. ''New York Times''. Nov 6, 1929.]] | [[Image:Atkinson_Bitter_Sweet_Review.jpg|thumb|Brooks Atkinson, 'Bittersweet' Here; Witty and Breezy. ''New York Times''. Nov 6, 1929.]] | ||

| + | |||

:My dear Merle, | :My dear Merle, | ||

:I saw an excellent play last night, George Kelly’s Maggie the Magnificent. If it comes to Chicago you might see it when you feel a little intelligent. It’s flopping here mainly because of the title, I think. I also saw Noel Coward’s Better Sweet, which isn’t brilliant as much as it’s brilliantine.<ref>Leo Adams to Merle Macbain, November 16, 1929.</ref> | :I saw an excellent play last night, George Kelly’s Maggie the Magnificent. If it comes to Chicago you might see it when you feel a little intelligent. It’s flopping here mainly because of the title, I think. I also saw Noel Coward’s Better Sweet, which isn’t brilliant as much as it’s brilliantine.<ref>Leo Adams to Merle Macbain, November 16, 1929.</ref> | ||

| − | Noel Coward's operetta '' | + | |

| + | Noel Coward's operetta ''Bitter Sweet'' opened at the Ziegfeld Theatre on November 5, 1929 and moved to the Shubert Theatre on February 17, 1930. The Act 3 quartet "Green Carnations" is sung by four London fops, including one whose name, Lord Henry Jade, seems to allude both to the dandiacal Lord Henry Wotton from Wilde's ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' and to Wilde's trademark green carnation. The number includes the following lyric: | ||

::Pretty boys, witty boys | ::Pretty boys, witty boys | ||

::You may sneer | ::You may sneer | ||

| Line 22: | Line 24: | ||

::Haughty boys, naughty boys, | ::Haughty boys, naughty boys, | ||

::Dear, dear, dear! | ::Dear, dear, dear! | ||

| − | ::Swooning with affectation | + | ::Swooning with affectation... |

::Faded boys, jaded boys | ::Faded boys, jaded boys | ||

| Line 31: | Line 33: | ||

::We all wear a green carnation. | ::We all wear a green carnation. | ||

| − | In his | + | In his review of the New York premier, Brooks Atkinson called the ensemble "a wry caricature of the Oscar Wildettes"<ref>J. Brooks Atkinson, "'Bittersweet' Here: Witty and Breezy." ''NY Times'', Nov 6, 1929, Pg. 30.</ref> The green carnation acquired its significance by association with Oscar Wilde and the ''fin-de-siècle'' aesthetes. As a symbol, the green carnation was "meant to confirm the wearer's interest in artifice," a central tenet of aestheticism.<ref>Talia Schaffer, "Fashioning Aestheticism by Aestheticizing Fashion: Wilde, Beerbohm, and the Male Aesthetes' Sartorial Codes," ''Victorian Literature and Culture'' Vol.28, no.1 (2000), pp.39-54.</ref> Wilde himself claimed to have invented the flower and the association became widespread after the publication in 1894 of Robert Hichens's satire of Wilde and ''fin-de-siècle'' aestheticism, ''The Green Carnation''. Hichens's book was used against Wilde in his trials for "gross indecency" in 1895 and, along with Wilde's name, the flower, when worn by men, became a signifier of homosexuality. |

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 28 October 2011

"You would be stimulated anew by contact with this strange and vital city. It remains elixir to me. It is inexhaustible."––Leo Adams to Merle Macbain, Jan 2, 1932

- My Dear Merle,

- Probably my only major accomplishment in New York has been such recognition as a small group gives me for remarkable conversation. I enjoy it immensely – the conversation. It keeps me from being lonely because it brings other people around; and it keeps me from being bored because other people are around; but it does not yet keep me a slave. When that happens I'll probably go Wilde.

- My dear boy, on thirty-five dollars a week I am living at a hotel which is luxurious and delightful; I see one or two plays (from the upper balcony, it is true, but I don't have to smell the actors to appreciate the play); I dine with several different people each week, choosing those who I feel most like talking at; I visit those ultra ultra spots where drinks cost a dollar each (though I get only one or two) and the like of which is nowhere else in this unfair country. You would have a delightful time here with me.[1]

At the time he wrote the above to his friend Merle Macbain, Leo Adams had recently moved into a bachelor apartment in The Shelton Hotel at 49th Street and Lexington Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. Since moving to New York in 1928, Adams had lived in a series bachelor apartments, including the 55th Street Allerton House and a hotel apartment at 136 West 55th Street. In his history, Gay New York, George Chauncey reports that by the mid 1920s, midtown Manhattan, especially the West 50s with its concentration of middle class bachelor apartments, rooming houses, theater employees, and speakeasies, had become something of a midtown Bohemia. The popular theater tabloid Broadway Brevities went so far as to dub the neighborhood the "Faggy Fifties."[2]

- My dear Merle,

- I saw an excellent play last night, George Kelly’s Maggie the Magnificent. If it comes to Chicago you might see it when you feel a little intelligent. It’s flopping here mainly because of the title, I think. I also saw Noel Coward’s Better Sweet, which isn’t brilliant as much as it’s brilliantine.[3]

Noel Coward's operetta Bitter Sweet opened at the Ziegfeld Theatre on November 5, 1929 and moved to the Shubert Theatre on February 17, 1930. The Act 3 quartet "Green Carnations" is sung by four London fops, including one whose name, Lord Henry Jade, seems to allude both to the dandiacal Lord Henry Wotton from Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray and to Wilde's trademark green carnation. The number includes the following lyric:

- Pretty boys, witty boys

- You may sneer

- At our disintegration.

- Haughty boys, naughty boys,

- Dear, dear, dear!

- Swooning with affectation...

- Faded boys, jaded boys

- Come what may

- Art is our inspiration

- And as we are the reason

- For the nineties being gay,

- We all wear a green carnation.

In his review of the New York premier, Brooks Atkinson called the ensemble "a wry caricature of the Oscar Wildettes"[4] The green carnation acquired its significance by association with Oscar Wilde and the fin-de-siècle aesthetes. As a symbol, the green carnation was "meant to confirm the wearer's interest in artifice," a central tenet of aestheticism.[5] Wilde himself claimed to have invented the flower and the association became widespread after the publication in 1894 of Robert Hichens's satire of Wilde and fin-de-siècle aestheticism, The Green Carnation. Hichens's book was used against Wilde in his trials for "gross indecency" in 1895 and, along with Wilde's name, the flower, when worn by men, became a signifier of homosexuality.

Notes

- ↑ Leo Adams to Merle Macbain, January 2, 1932. Leo Adams Papers, New York Public Library (Hereafter cited by name and date only).

- ↑ George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994).

- ↑ Leo Adams to Merle Macbain, November 16, 1929.

- ↑ J. Brooks Atkinson, "'Bittersweet' Here: Witty and Breezy." NY Times, Nov 6, 1929, Pg. 30.

- ↑ Talia Schaffer, "Fashioning Aestheticism by Aestheticizing Fashion: Wilde, Beerbohm, and the Male Aesthetes' Sartorial Codes," Victorian Literature and Culture Vol.28, no.1 (2000), pp.39-54.

Back to Leo Adams: A Gay Life in Letters, 1928–1952

<comments />