Difference between revisions of "Out in Black Magazine"

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

[[File:ExecutiveBoard.jpg]] <ref> John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.3, 1996 </ref> | [[File:ExecutiveBoard.jpg]] <ref> John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.3, 1996 </ref> | ||

| − | + | Major staff writers for Out in Black from left to right: Jerry Harris (co-publisher), Rodney P. Hunter, Tolanda McKinney, and John Hardy (editor-in-chief and founder) | |

The first issue was released for the months of July and August in 1996 (Volume 1.1). Hardy was joined by publisher Jerry Harris for the next issue for the months of September/October, Volume 1.2, also in 1996. Harris is a personal friend of Hardy as well as publisher of the Black Men United report which also reported bi-monthly. Harris decided that instead of doing two separate magazines targeted at the same idea, Hardy bring him on as a publisher so they could work towards their common goal. Rodney Hunter first submitted a piece into the magazine and then became more involved as an editor while still submitting his own piece. Until the November/December issue in 1996 (Volume 1.3), the magazine was strictly a male-centered publication with only male views about men ‘in the life’ in the Durham and Raleigh area. This is when writer Tolanda McKinney came into the ''Out in Black'' family and began to write articles from a female perspective as well as encourage female writers in the area to submit their material knowing for more diversity in the magazine. | The first issue was released for the months of July and August in 1996 (Volume 1.1). Hardy was joined by publisher Jerry Harris for the next issue for the months of September/October, Volume 1.2, also in 1996. Harris is a personal friend of Hardy as well as publisher of the Black Men United report which also reported bi-monthly. Harris decided that instead of doing two separate magazines targeted at the same idea, Hardy bring him on as a publisher so they could work towards their common goal. Rodney Hunter first submitted a piece into the magazine and then became more involved as an editor while still submitting his own piece. Until the November/December issue in 1996 (Volume 1.3), the magazine was strictly a male-centered publication with only male views about men ‘in the life’ in the Durham and Raleigh area. This is when writer Tolanda McKinney came into the ''Out in Black'' family and began to write articles from a female perspective as well as encourage female writers in the area to submit their material knowing for more diversity in the magazine. | ||

Revision as of 11:32, 21 April 2012

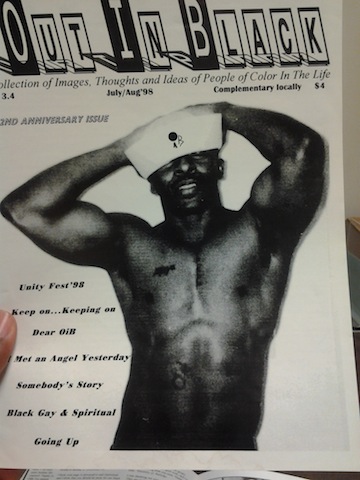

Out in Black Publications was founded in the summer of 1996 by John Hardy, a graduate of North Carolina State University and writer who lived in Raleigh, North Carolina. He funded, edited, wrote, collected stories, and distributed the free first issue of Out in Black by himself at local night clubs, in bookshops, through word of mouth, and through orders made by anyone who was interested in seeing his work. Out in Black Publications is a bi-monthly publication by and for people of African descent ‘in the life’ to provide this community with news and information related to black issues. The phrase ‘in the life’ is used throughout the magazine and it signifies living in a country where your existence as a sexual, gender, and racial minority is looked down upon and for the most part, not wanted. Their goal was to educate and motivate the African American community and to bridge gaps in understanding surrounding issues of health, politics, sexuality, religion, gender expression, and most importantly: living in a world where your existence is not wanted. Out in Black was based out of the Raleigh and Durham area whose target audience includes people of African descent living ‘in the life’.

HIV/AIDS Sex/Sexuality Personal Acceptance Race Religion Sources

History of the Executive Board

[1]

Major staff writers for Out in Black from left to right: Jerry Harris (co-publisher), Rodney P. Hunter, Tolanda McKinney, and John Hardy (editor-in-chief and founder)

[1]

Major staff writers for Out in Black from left to right: Jerry Harris (co-publisher), Rodney P. Hunter, Tolanda McKinney, and John Hardy (editor-in-chief and founder)

The first issue was released for the months of July and August in 1996 (Volume 1.1). Hardy was joined by publisher Jerry Harris for the next issue for the months of September/October, Volume 1.2, also in 1996. Harris is a personal friend of Hardy as well as publisher of the Black Men United report which also reported bi-monthly. Harris decided that instead of doing two separate magazines targeted at the same idea, Hardy bring him on as a publisher so they could work towards their common goal. Rodney Hunter first submitted a piece into the magazine and then became more involved as an editor while still submitting his own piece. Until the November/December issue in 1996 (Volume 1.3), the magazine was strictly a male-centered publication with only male views about men ‘in the life’ in the Durham and Raleigh area. This is when writer Tolanda McKinney came into the Out in Black family and began to write articles from a female perspective as well as encourage female writers in the area to submit their material knowing for more diversity in the magazine.

HIV/AIDS

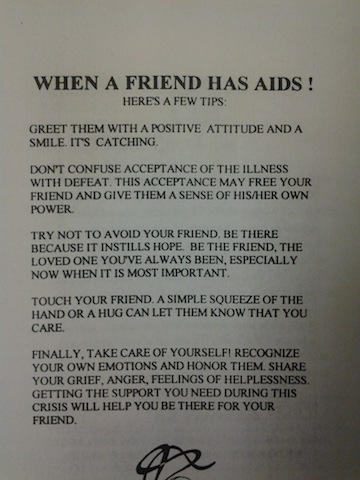

Out in Black magazine began its journey at the fringes of the major AIDS scare that occurred in the 1980s so AIDS treatment, prevention, education, and ways to get tested were one of the forefront topics used throughout every issue. In the first issue, HIV/AIDS was just referred to as the ‘AIDS epidemic’ that was affecting the community of color and specifically a focus on gay and bisexual black men. The lack of information to the community of color about how HIV was contracted first and then without treatment, HIV evolves itself into AIDS was not available at the time so people of color referred this virus as strictly ‘AIDS’. It was not until the September/October 1996, Volume. 1.2 issue where there was an ad that specifically speaks out against HIV. Within the first issue (July/August 1996, Volume 1.1) some of the stories regarding AIDS were: the prevalence of AIDS in the black and Latino community (both men and women of different sexual orientations) versus the white population, a piece on how to deal with a friend who has HIV/AIDS, as well as numerous ads within the magazine promoting people to get tested at their local clinic and to participate in safe sex. In the second issue (September/October 1996, Volume 1.2) the mention of HIV as an epidemic instead of AIDS as an epidemic is noted, there is further explanation of how it can be contracted, how it is affecting the black community, and preventative steps in order to promote healthy living.

Sex/Sexuality

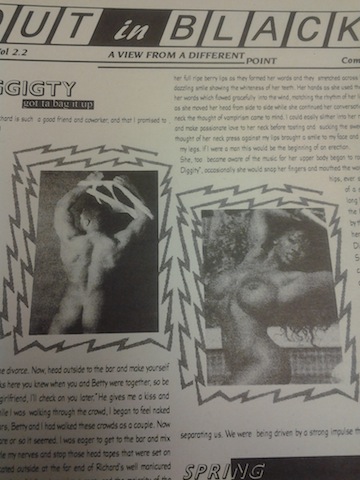

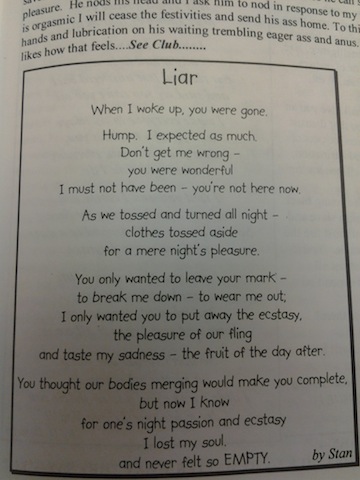

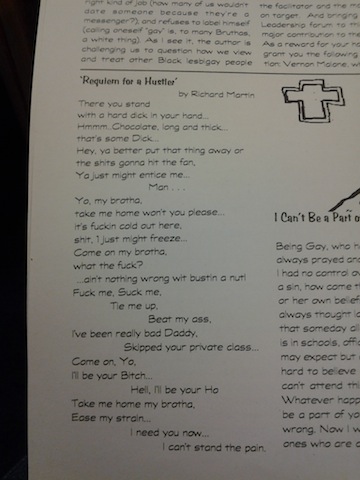

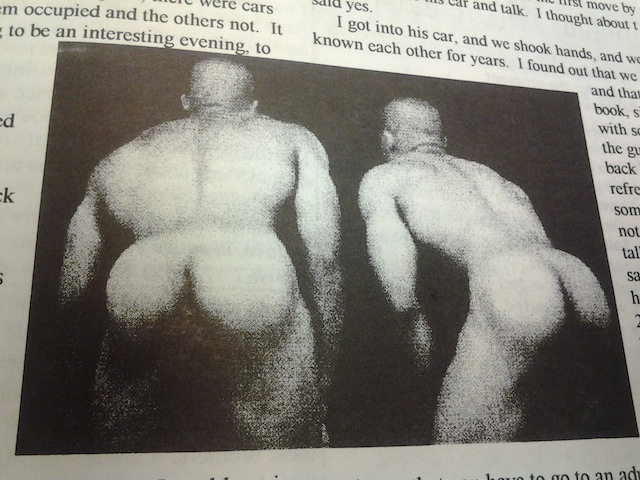

Issues of sexuality as far as being sexually promiscuous, homosexuality, and bisexuality were expressed through articles and poetry submitted to the magazine, however the most visual form of sex and sexuality were in the pictures plastered all throughout these magazines. Whether they were actual people or cartoons in sexually compromising positions or poses, the provocative sexual imagery demonstrated throughout this magazine expressed the importance of sex-related issues during the late 1990s culture for African people living ‘in the life’. The sexual encounters written in some of these articles display passion, if only just for one night, between these lovers with exquisite detail to the point where one can envision a porno in their minds when reading some of these pieces. The poems dive right into the heart of black sexuality at the time as well ranging from a plea to be taken home by a stranger to the feeling of emptiness after having a one-night stand. Out in Black magazine also sold space for Personal Ads where people (usually men) in the life could post an ad for sex and contact information in the magazine. This was one of their best ways of raising revenue for the magazine besides subscribing people to the mailing list.

Personal Acceptance

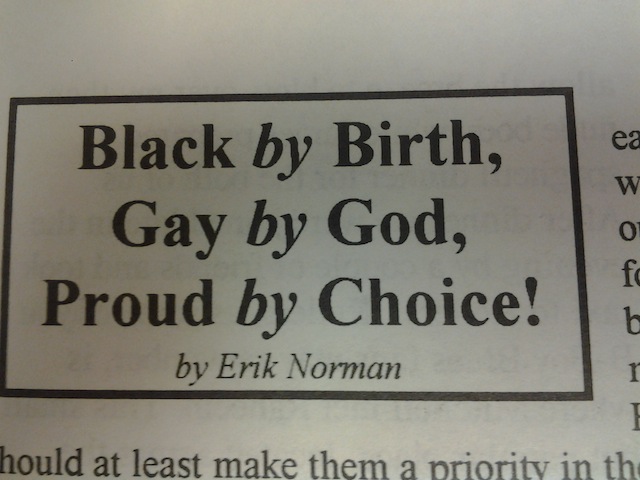

Throughout the Out in Black issues, the common theme of self-actualization and coming to terms with the many identities one deals with on a daily basis was a key factor in helping the community self-heal themselves and be able to have pride in who they are. The two main aspects in which personal acceptance were spoken about in Out in Black were one’s race and one’s religious background.

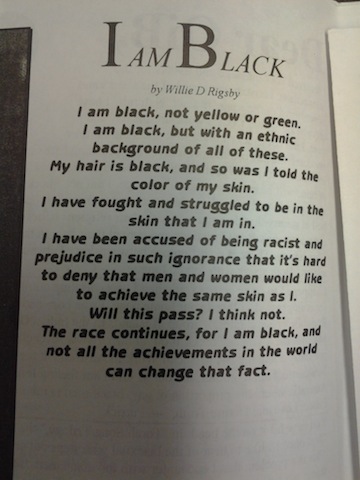

Race

Living in the late 1900s was still a period where racism was ever present in common social interactions in between white people and people of color. There was a story printed in the first issue about clubs not having ‘Black Nights’ where lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons of color could go out to the club and have a good time. The clubs in the area got angry when a story was printed about them not being inclusive however the truth was they were not catering to a population that was willing to ‘pay to play’ however they were excluded because of their race. Where a black man, gay or bisexual, is always thought of to be the next criminal, thug, drug dealer, gang member, or all around low-life in the eyes of the dominant white population, having a black identity is a constant struggle in America.

Religion

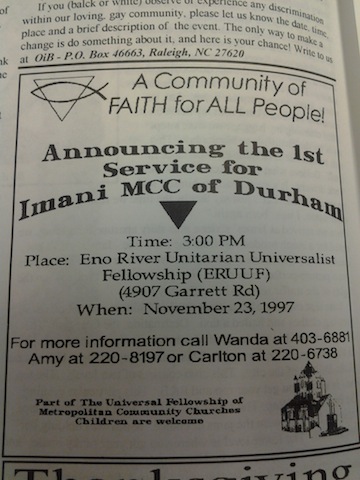

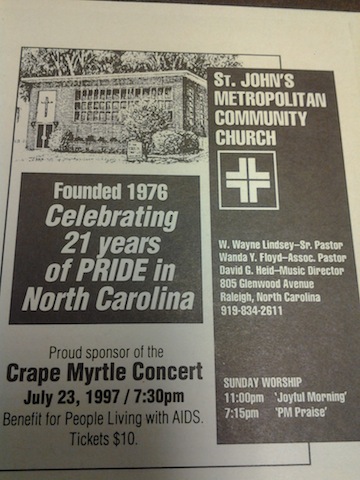

The black community has roots in the church seeing as that was a place from which they gathered strength from through prayer and worship to overcome obstacles such as slavery and segregation. However the black church has not been a beacon of light for its entire congregation. Many gay, lesbian, and bisexual people of color felt ostracized from the congregation when messages of hate for homosexuality were preached and gladly welcomed into the church community. This disconnect from a major pillar from which many of the black community as an entirety grew up on caused internal suffering, angst, wonder, frustration, and loneliness from religion as a whole. People began to question why God had made them this way where in the world they lived in, they were not accepted by modern society. There were people who still found strength in religion even though messages of hate were spewed at them however many felt justified in cutting off all ties with religion, churches, and any higher power that people may pray to. Out in Black encouraged their readers to find solace in a higher power with the ads they posted about accepting churches who were there to help all humanity and different pieces about finding religion even thought identifying as homosexual or bisexual.

Sources

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.3, 1996

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.1, 1996

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.1, 1996

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.2, 1996

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.3, 1996

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.1, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.2, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 3.4, 1998

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.3, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.4, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 1.1, 1996

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.7, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 3.2, 1998

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.4, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 3.4, 1998

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 3.4, 1998

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.7, 1998

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.1, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.3, 1997

- ↑ John, Hardy. Out in Black, Volume 2.3, 1997

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 1.1, 1996

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 1.2, 1996

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 1.3, 1996

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 2.1, 1997

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 2.2, 1997

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 2.3, 1997

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 2.4, 1997

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 2.7, 1997

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 3.2, 1998

- ↑ Hardy, John. Out in Black, Volume 3.4, 1998

Edited By: Adryen Proctor