Difference between revisions of "Americans in Württemberg Scandal, 1888/Part 4"

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

The threat of Jackson’s own prosecution, and the public scandal surrounding Karl Mann’s trial, was too much for the American who had brought the blackmail charges. During Mann's trial, Richard Mason Jackson left Stuttgart for the United States. Returning, briefly, to Steubenville, Ohio, he apparently ended his days with a sister elsewhere in the state, resuming "the part of a plain citizen of the United states of America. "<ref>Sinclair, ''Pioneer Days'', 132-33. Katz's efforts to locate Jackson's death certificate in Ohio were unsuccessful.</ref> The "Buckeye boy" did go home again. | The threat of Jackson’s own prosecution, and the public scandal surrounding Karl Mann’s trial, was too much for the American who had brought the blackmail charges. During Mann's trial, Richard Mason Jackson left Stuttgart for the United States. Returning, briefly, to Steubenville, Ohio, he apparently ended his days with a sister elsewhere in the state, resuming "the part of a plain citizen of the United states of America. "<ref>Sinclair, ''Pioneer Days'', 132-33. Katz's efforts to locate Jackson's death certificate in Ohio were unsuccessful.</ref> The "Buckeye boy" did go home again. | ||

| + | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 18:24, 31 July 2008

Continued from Americans in Württemberg Scandal, 1888/Part 3

By Jonathan Ned Katz. Copyright (c) by Jonathan Ned Katz. All rights reserved.

(In this, Part 4, the note numbers begin again at 1.)

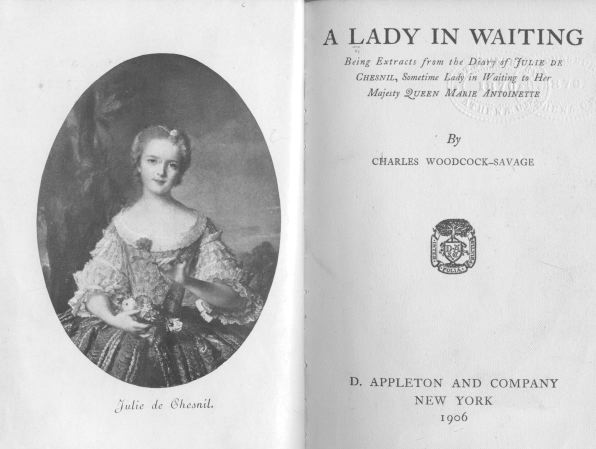

A Lady in Waiting

One last major document reveals the world according to Woodcock--and, probably, Hendry. In February 1906, "Charles Woodcock-Savage" published, with the respectable New York firm of D. Appleton, a novel titled A Lady in Waiting: Being Extracts from the Diary of Julie de Chesnil, Sometimes Lady in Waiting to Her Majesty, Queen Marie Antoinette.[1]

The novel, written as the diary of Julie de Chesnil, a young aristocrat, detailed her adventures during and after the French Revolution of 1789. Julie was Woodcock's literary stand-in, and the fictional form allowed the author to comment indirectly on his own adventures in King Karl's court. This is a novel with a key.

Madame de Polignac, for example, who introduces Julie to the court of Marie Antoinette, warns the heroine about the intrigues of the "little nobility -- those creatures who owe their all to the present reign, and were created by it; for they are candidates ... for any gilded plum it is in the royal power to bestow; and if another receive it instead, they snarl and growl"--exactly Woodcock's experience of Wtirttemberg's courtiers.

De Polignac adds, "When I refused all official connection with the Court, it was, in their eyes, that I might be better able to concoct all kinds of plans in secret. As soon as I accepted a position at Court ... l was accused of interfering with affairs of State....[2]

Woodcock's feeling for King Karl is represented in the novel by Julie de Chesnil's for Marie Antoinette: After Julie meets the Queen for first time and is warmly welcomed, she imagines the very trees congratulating her: "'for thou art youthful, and hast seen the Queen and gained her confidence....[3] Says Julie of the Queen: "The more I see of her, the greater becomes my admiration for her noble character."[4] Woodcock's novel is dedicated to "To the Memory of a Noble Soul I Knew and Loved and Mourn" -- King Karl, who had died in 1891.

"Love" and "admiration" are the major terms signifying Julie's feeling for her Queen, and, by extension, Woodcock's for King Karl. Sexual desire and acts are alluded to in Woodcock's novel, but only to be denied.

An angry revolutionary deputy refers to rumors of the French Queen's "wildest; orgies with foreigners." Julie assures him, however, that he has "been led into error by listening to stories, the product of the wildest fancy.., disseminated by those who were the Queen's enemies ... [who] in this way sought to injure her."[5] Here, a chaste Queen substitutes for Woodcock's idealized, "noble" King. Reference is also made to stories about the Queen "of the vilest character -- stories which only a devilish ingenuity could invent, and the tongue of malice repeat....[6]

A specifically lesbian eros appears briefly in the novel when Julie de Chesnil, disguised as a young man to escape execution by French revolutionaries, is embraced "with great ardor" by a girl who exclaims, "'I love thee! I love thee! '" Julie's only response is puritanical: "God forgive me for inspiring such a passion, even though unwillingly."[7]

But at this novel's formulaic happy end, after escaping the terrors of the French revolution, and while recounting her adventures to none other than Emperor Napoleon and Empress Josephine, Julie admits: "I am too fond of theatrical effects not to have used the material at my command in such a way as to make the greatest possible impression upon their Majesties, while reserving all detail of a private nature as too sacred for other ears....[8] Woodcocock' s mouthpiece ends with the coy admission that she's not telling everything -- certainly not the most "private," "sacred" details--thereby reinstating sex-love as that which can't be named in this autobiographical fiction.

After Julie escapes France on an American ship, she arrives in New York City, and reports that "A highly embellished account of my sad history appeared in their daily papers shortly after my arrival, and I certainly cannot complain of neglect since then"--ironic comment on the press coverage of Woodcock's exploits.[9]

In America, Julie dines with Mrs. John Jay, and Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Hamilton, and meets a Reverend Doctor John Rogers who very probably satirizes the Reverend Doctor George Hepworth (who had passed heavenward in 1902).[10]

Reverend Rogers is "considered a social leader" because his name is "never absent from any dinner list." For "a stranger to be taken in by him means having the entree everywhere." Rogers' manners are so "stiff and formal" it's said that "he and his wife 'always salute each other with a formal bow and curtsy before retiring for the night'"--a sly comment, perhaps, on Hepworth's lack of enthusiasm for marital copulation. Asked if anyone equals Dr. Rogers in "majestic dignity," the narrator thinks: "I had seen a dignity which was a pretty good imitation of it on the stage."[11] Reverend Hepworth had taken acting lessons in preparation for the popular pulpit.[12]

The book's satire also extends to the land of the free. Julie is invited to a New York dinner party catered by many servants, "which is rare here as the democratic spirit of the people is strongly against servitude .., which is all the stranger because a large number of the people of this New Republic are held in perpetual bondage. But then ... this is a country of strange paradoxes!"[13]

At the novel's end, Julie is visiting George and Martha Washington, at Mount Vernon, meets her long lost fiancé, and is married in Alexandria, Virginia, with President Washington giving away the bride.[14]

Authorship

Woodcock's Lady in Waiting contains repeated, self-reflective comments on the "diary" that supposedly comprises it, and, by extension, Woodcock's and Hendry's memoirs. The novel is introduced by "a heartless old bachelor" (Hendry's stand-in) who presents the diary to the public, relating "all the struggles I passed through before I could make up my mind to let that voice of the past, which had spoken to us so sweetly and thrillingly in the night, speak to the public ear." That "us" refers to the bachelor narrator and his intimate male friend (Woodcock's stand-in), suggesting that Woodcock and Hendry worried together over the advisability of publishing this roman a clef.

The device of the bachelor narrator and his friend, Paul du Laurier, a married artist and "the happy father of four promising boys," also strongly suggests that Hendry was the actual, or, at least, co-author of this novel.

The narrator's friend, Du Laurier, is said to have found Julie de Chesnil's diary locked in a "secret drawer" in a "Louis Seize cabinet" bought at auction. The narrator admits that he is "not so heartless that my eye will not moisten, and a sigh escape me, every time I take from their hiding place those yellow leaves which Du Laurier gave me just before he married."[15] Just before Woodcock married, did he give Hendry his diary of their Wurttemberg adventures? If so, did Hendry hide that diary in the secret drawer of a cabinet in his possession?

Julie, the novel's heroine, also muses on the revivifying effect of reading one's old diary long after writing it: "By turning over these pages I can live my life over again," and, she adds, "they may prove of interest to those who come after me."[16] Julie correctly anticipates our interest.

History

Finally, as "a young lady who lived in one of the most interesting periods of French history," Julie has her eyes opened to the problem of conflicting standpoints on the past. She realizes "how falsely human history may be written; not necessarily, as I had supposed till now, because of distortion of facts; but because, even in the case of an eyewitness who tells the truth, it is, after all, only the truth as he sees it."[17] Comparing the views of French revolutionaries with her own aristocratic outlook, Julie (and Woodcock, and, probably Hendry) understands that one's class position profoundly colors one's take on history.

Through Julie, Woodcock presented his relationship with King Charles as affectionate and asexual--but ended by hinting that he had left out some juicy details. In contrast, Bismarck's private investigation of Woodcock strongly hinted at sex, and pointed to the ruler's exploitation, the American's self-aggrandizement and misrepresentation.

Woodcock's and Hendry's Last Resting Place

Charles Woodcock Savage died suddenly in New York City on June 26, 1923, at the age of seventy-three."[18] He was buried in his wife's family plot in Trinity Cemetery, on Riverside Drive and West 153rd Street, where his grave may be visited.[19] Earlier, thanks to his marriage, he had provided a last resting place in the same plot for his mother and father. His wife, Henrietta, died on March 3, 1934, and was buried next to her husband.

Before Henrietta Savage's death, Donald Hendry made his will on March 23, 1932, using as his lawyer, Henrietta's son (Charles Woodcock's adopted son), Joseph K. Savage. Hendry had remained friends with the family.

Hendry's 1932 will directed that his ashes be interred "in the family burial plot at Benton," New Brunswick, Canada, "where my father and mother are buried." But, in 1934, after Henrietta Savage's death, Hendry changed his will, adding a codicil. He then asked that "my body be cremated and my ashes buried next to the body of my friend Charles B. Woodcock Savage."[20]

When Hendry died on November 26, 1935, at the age of eighty-one, his New York Times obituary (following, probably, a resume he had prepared for an employer) said that he had spent "eleven years in Europe as a private secretary"--his way of publicly naming his years with Woodcock. Today, Hendry's gravestone in Trinity Cemetery, lies between and just above those of Charles Woodcock Savage and his wife.

Hendry's probated will shows that he bequeathed to one sister a five-piece, German, silver tea set (a Wuirttemberg relic?), to another sister a "carved cabinet (poor condition)." Did this cabinet by any chance contain a "secret drawer" holding some yellowed papers? Hendry's other possessions included a "Gold Snake ring - with turquoise," a "Gold watch chain -broken," a "Gold stick pin - with small pearl and diamond," a "Wall thermometer," a "Small Philco Radio," an "Upholstered leather arm chair -(worn)," a "Lot of miscellaneous plain pictures and portraits" (including, no doubt, a now rare photo of Woodcock), another "Lot of miscellaneous books and pamphlets," and a "canvas - (old and worn)." For tax purposes, his estate was estimated as worth $1,929.51 (about $22,000 today).

A memorial to Hendry in the Pratt Institute Students' Bulletin reports that, in 1914, he had represented the American Library Association at a book exhibition in Leipzig: "When war was declared his knowledge of the language and the people proved indispensable in rescuing Americans stranded in Germany." Hendry had "often asserted that his work was his sole interest, and, as he never married, the Library took the place of home and family to him." Hendry had died in Ridley Park, Pennsylvania, where he had "lived with friends" after retiring from the library in June 1934.[21]

Jackson's Later Life

The later history of Richard M. Jackson, the American who preceded Woodcock in the King Karl's affection, provides a final, unexpected twist to this story of two Yankees and one Canadian at King Karl's court.[22] Jackson survived Woodcock's and Hendry 1888 exile, completely untouched by scandal. Even after the death of King Karl, in 1891, Jackson maintained his position in Stuttgart society.

But between 1890 and 1892, a house servant, Karl Mann, who had worked for Jackson in the 1880s, extorted 1075 marks from his former employer, threatening to denounce him to the police for engaging him in illicit sexual acts.<ref. Karl Mann had worked for Jackson from 1881 to 1884.</ref> Taking a most unusual and courageous step, Jackson finally lodged a blackmail complaint against Mann in 1893.

In the legal action that followed, Karl Mann countercharged that Jackson had "used his servant not merely for the allowed servant's duties .. , but had also used his person for the practice of ongoing indecent acts." The thirty-six-year old Mann was found guilty of blackmail and sentenced to six months in prison--the judge explaining that the "intimate relationship" of servant and master had tempted Mann to perform the sexual acts admitted by him. Supposedly, his subservient class position, not his desire, explained Mann's acts.

In 1893, this legal case provided ammunition with which the newspapers of the German Social Democratic party attacked the immoral behavior of the upper classes. One of those papers, recalling the King's "generous gifts to Jackson," remarked sarcastically that the American "must have been of quite extraordinary service to the person of the deceased king"--sexual service was suggested.[23] Jackson, the paper continued, had "for long years practiced an abominable vice, the crime against nature."

The Social Democratic paper added that this "vice of pederasty has grown in the finer circles of Stuttgart to an extraordinary extent." Recent rumor had it that "a number of persons" now "draw their entire income from this vice," and can "therefore be considered . . . 'male prostitutes.'"[24] The quote marks suggest that in 1893 "'male prostitutes'" -- meaning, specifically, men who sold their sexual services to men -- were still new to German newspaper readers, as they probably were to that day's Americans.

The threat of Jackson’s own prosecution, and the public scandal surrounding Karl Mann’s trial, was too much for the American who had brought the blackmail charges. During Mann's trial, Richard Mason Jackson left Stuttgart for the United States. Returning, briefly, to Steubenville, Ohio, he apparently ended his days with a sister elsewhere in the state, resuming "the part of a plain citizen of the United states of America. "[25] The "Buckeye boy" did go home again.

References

- ↑ Charles Woodcock-Savage, A Lady in Waiting. Katz consulted the copy at the New York Public Library Research Center. He thanks Michael S. Montgomery for informing him that a copy in the Clemson University Llibrary, Clemson, South Carolina, contains a brief note by an acquaintance of Woodcock-Savage, "RAE": "He was of an interesting personality of many undercurrents and a fine example of the aristocracy he portrays. I knew him well in my office, in his home and in my own apartment. It was there he dropped in to see me on his weekly visits ... to Upper Trinity Cemetery [sic] to place flowers on his mother's grave." Lackluster reviews of the novel appeared in The New York Times, May 19, 1906, 322; The Critic, July 1906, 94; and Outlook, 82, March 24, 1906, 32Z. Woodcock-Savage's novel was republished in German as Die Hofdame der Konigin (1907).

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, pp. 132-33.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 140.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 152.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 168.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 176.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 244.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 319.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 257. The novel hints at greater American press coverage than has so far been discovered.

- ↑ Ward, p. 270.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, pp. 262-63.

- ↑ Ward, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, pp. 266-68.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 297.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 6.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 166.

- ↑ Woodcock-Savage, p. 6, 103.

- ↑ A brief death notice of "Charles B. Woodcock Savage" is in The New York Times, June 28, 1923, p. 15; Woodcock's death certificate is #17676 1923, New York City Municipal Archives; Katz thanks Joel Honig for this information.

- ↑ The Woodcock Savage and Hendry graves are in Plot No. 185 Westerly Division; Gail Pezzuto, Manager, Client Account Services, Trinity Church, Cemetery/Mausoleum Department, to Joel Honig, January 27, 1998, including photocopies of information cards on the Knebel, Woodcock, and Savage families, and Donald Hendry. Katz is indebted to Honig for this wonderful information. Dates on the information card differ sometimes with dates on the tombstones.

- ↑ For Hendry's will of March 23, 1932, and his codicil of July 2, 1934, see Estate 131, 1936, Kings County, New York, Municipal Archives. Katz is indebted to Joel Honig for discovering this important document, and providing a photocopy. Hendry's two sisters, Lilly and Susan, lived in Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada.

- ↑ "The Library," Students' Bulletin.

- ↑ For this part of Jackson's life see Dworek, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Dworek, p. 14, quoting the Swabische Tagwacht, of February 18, 1893.

- ↑ Dworek, p. 14.

- ↑ Sinclair, Pioneer Days, 132-33. Katz's efforts to locate Jackson's death certificate in Ohio were unsuccessful.