Difference between revisions of "Twin Cities Pride Parade"

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

! | ! | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | The Twin Cities Pride Parade began as a 50-strong protest march on the (newly-built) Nicollet Mall in 1972. Downtown shoppers and office workers composed a majority of the event's few spectators, and of these, few had “the foggiest idea what [the marchers] were talking about.” Americans were still fighting in the Vietnam War, and this produced countless protest marches. Gay Pride appeared to be just another slogan on hand-painted pickets; the concept garnered little attention. | + | | The Twin Cities Pride Parade began as a 50-strong protest march on the (newly-built) Nicollet Mall in 1972. Downtown shoppers and office workers composed a majority of the event's few spectators, and of these, few had “the foggiest idea what [the marchers] were talking about.”<small>(1)</small> Americans were still fighting in the Vietnam War, and this produced countless protest marches. Gay Pride appeared to be just another slogan on hand-painted pickets; the concept garnered little attention. |

| − | Gay Pride attracted substantial attention in 1977, when Anita Bryant—an advocate for anti-gay legislation—stirred a backlash in the young LGBT community. | + | Gay Pride attracted substantial attention in 1977, when Anita Bryant—an advocate for anti-gay legislation—stirred a backlash in the young LGBT community nation-wide. That year, scores of simple floats and walking drag queens accompanied defiant marchers holding hands--all with the purpose of lending visibility to queer love and expression. |

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | In 1987, the Committee chose a route away from Loring Park that stretched from Lake Calhoun to Powderhorn Park along 32nd street. The 2-mile path exhausted participants, bored attendees, and threatened to event’s future. Some even referred to that year's parade as "the death march." | + | In 1987, the Committee chose a route away from Loring Park that stretched from Lake Calhoun to Powderhorn Park along 32nd street. The 2-mile path exhausted participants, bored attendees, and threatened to event’s future. Some even referred to that year's parade as "the death march."<small>(2)</small> |

{| {{prettytable}} | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

<small>'''Ashley Rukes on the cover of Gaze Magazine, 1993. Courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | <small>'''Ashley Rukes on the cover of Gaze Magazine, 1993. Courtesy of the [[Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection]].'''</small> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |Hope came in the form of a transgender woman with a penchant for military fashion. Ashley Rukes, who directed the Aquatennial Parade in 1975, first volunteered her expertise in 1992. Rukes initiated communication with Minneapolis Police, established a pioneering lineup system for the parade’s many contingents, and encouraged even the smallest groups to participate. | + | |Hope came in the form of a transgender woman with a penchant for military fashion. Ashley Rukes, who directed the Aquatennial Parade in 1975, first volunteered her expertise in 1992. Rukes initiated communication with Minneapolis Police, established a pioneering lineup system for the parade’s many contingents, and encouraged even the smallest groups to participate.<small>(3)</small> |

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

| − | Shock and sadness met the Director’s untimely death shortly before pride weekend in 1999. The Pride Committee now names the | + | Shock and sadness met the Director’s untimely death shortly before pride weekend in 1999.<small>(4)</small> The Pride Committee now names the Twin Cities Pride Parade in her honor.<div style="text-align: center;"> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| + | <small>(1)</small> Tretter, Jean-Nickolaus. Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. January, 2009. | ||

This page is still under contruction. --SVC | This page is still under contruction. --SVC | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>(2)</small> Hill, David Wayne. Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. May, 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>(3)</small>"Parade Coodinator Ashley Rukes Rounds up Family of Pride." ''Twin Cities Gaze'', Issue 193: January 28, 1993. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <small>(4)</small>Twin Cities Pride Guide, 1999. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies. | ||

Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | Part of [[Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)]] | ||

Revision as of 22:33, 27 February 2010

Nicollet Avenue, Marquette Avenue, 24th Street W., Lyndale Avenue, and 32nd Street by various routes, (1972-2010)

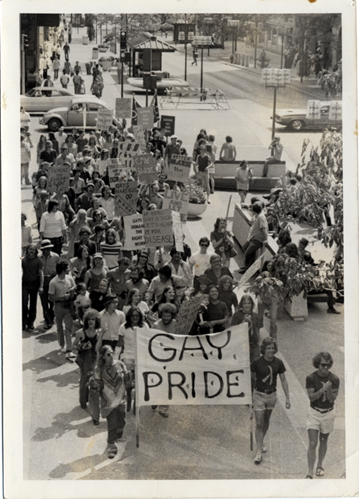

| The Twin Cities Pride Parade began as a 50-strong protest march on the (newly-built) Nicollet Mall in 1972. Downtown shoppers and office workers composed a majority of the event's few spectators, and of these, few had “the foggiest idea what [the marchers] were talking about.”(1) Americans were still fighting in the Vietnam War, and this produced countless protest marches. Gay Pride appeared to be just another slogan on hand-painted pickets; the concept garnered little attention.

|

The second Twin Cities Pride March on the Nicollet Mall, 1973. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

In 1987, the Committee chose a route away from Loring Park that stretched from Lake Calhoun to Powderhorn Park along 32nd street. The 2-mile path exhausted participants, bored attendees, and threatened to event’s future. Some even referred to that year's parade as "the death march."(2)

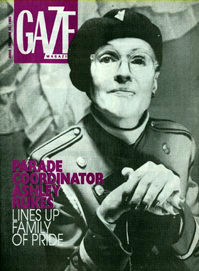

| Ashley Rukes on the cover of Gaze Magazine, 1993. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

Hope came in the form of a transgender woman with a penchant for military fashion. Ashley Rukes, who directed the Aquatennial Parade in 1975, first volunteered her expertise in 1992. Rukes initiated communication with Minneapolis Police, established a pioneering lineup system for the parade’s many contingents, and encouraged even the smallest groups to participate.(3)

|

(1) Tretter, Jean-Nickolaus. Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. January, 2009. This page is still under contruction. --SVC

(2) Hill, David Wayne. Interview with the author and Jacob Gentz. May, 2009.

(3)"Parade Coodinator Ashley Rukes Rounds up Family of Pride." Twin Cities Gaze, Issue 193: January 28, 1993.

(4)Twin Cities Pride Guide, 1999. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies.

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)