Difference between revisions of "Twin Cities Black Pride"

(table) |

|||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|<div style="text-align: center;"> | |<div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| − | [[Image:Blackpride.jpg]] <div style="text-align: center;"> | + | [[Image:Blackpride.jpg]] |

| − | + | </div> <small><div style="text-align: center;"> | |

| + | '''Twin Cities Black Pride Logo, 2009.'''</small> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Physical testaments to Minneapolis’ industrial past continuously vanish from the urban landscape—railroads disappear and become bicycle paths; factories vanish and shopping malls take their place; even old warehouses experience rebirth as luxurious apartments. These changes are especially evident at the place of the Twin Cities’ genesis—The [[Mississippi River]]. Either embankment of the waterway provided the most level grade for interurban railroads; by the 1920s, much of the downtown riverfront was a hopeless tangle of rail lines and maintenance yards.<small>(1)</small> | | Physical testaments to Minneapolis’ industrial past continuously vanish from the urban landscape—railroads disappear and become bicycle paths; factories vanish and shopping malls take their place; even old warehouses experience rebirth as luxurious apartments. These changes are especially evident at the place of the Twin Cities’ genesis—The [[Mississippi River]]. Either embankment of the waterway provided the most level grade for interurban railroads; by the 1920s, much of the downtown riverfront was a hopeless tangle of rail lines and maintenance yards.<small>(1)</small> | ||

| Line 20: | Line 21: | ||

| − | The railroads may have been a terrible steward of the environment, yet the Great Northern once employed many in the local African-American community. Working as “porters” ( i.e. carriers of luggage, waiters, attendants of sleeping cars), these individuals earned stable (if woefully unequal) pay long before the Civil Rights Movement spurred equal-hiring practices in other companies and industries.<small>(3)</small> The Great Northern Railway merged with other railroads in the early 1970s, and Boom Island languished for years an abandoned and polluted industrial site. In 1987, the City of Minneapolis cleaned the site, built a marina, and returned the park to its pre-industrial state.<small>(4)</small> | + | |

| + | {| {{prettytable}} | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | The railroads may have been a terrible steward of the environment, yet the Great Northern once employed many in the local African-American community. Working as “porters” ( i.e. carriers of luggage, waiters, attendants of sleeping cars), these individuals earned stable (if woefully unequal) pay long before the Civil Rights Movement spurred equal-hiring practices in other companies and industries.<small>(3)</small> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The Great Northern Railway merged with other railroads in the early 1970s, and Boom Island languished for years an abandoned and polluted industrial site. In 1987, the City of Minneapolis cleaned the site, built a marina, and returned the park to its pre-industrial state.<small>(4)</small> | ||

| + | |<div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | [[Image:Svc_porter.jpg]] | ||

| + | </div> <div style="text-align: center;"> | ||

| + | <small>'''A Twin Cities railroad porter in 1935. Image Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.'''</small> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| Line 26: | Line 41: | ||

| − | The event blended an past site of restrictive employment with a present cause for celebration—the Black queer community grows and flowers | + | The event blended an past site of restrictive employment with a present cause for celebration—the Black queer community grows and flowers much as the island does. |

Revision as of 21:07, 15 March 2010

North of Nicollet Island on the Mississippi River

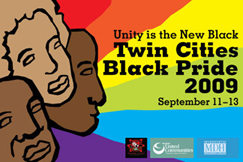

| Twin Cities Black Pride Logo, 2009. |

Physical testaments to Minneapolis’ industrial past continuously vanish from the urban landscape—railroads disappear and become bicycle paths; factories vanish and shopping malls take their place; even old warehouses experience rebirth as luxurious apartments. These changes are especially evident at the place of the Twin Cities’ genesis—The Mississippi River. Either embankment of the waterway provided the most level grade for interurban railroads; by the 1920s, much of the downtown riverfront was a hopeless tangle of rail lines and maintenance yards.(1) |

Once a wooded islet to the north of Nicollet Island, Boom Island was an alarming example of the railroad’s encroachment. The entire island was stripped of vegetation and became a yard for the Wisconsin Central Railroad and Great Northern Railway—the companies even filled the island’s northern channel to connect it to the mainland.(2)

| The railroads may have been a terrible steward of the environment, yet the Great Northern once employed many in the local African-American community. Working as “porters” ( i.e. carriers of luggage, waiters, attendants of sleeping cars), these individuals earned stable (if woefully unequal) pay long before the Civil Rights Movement spurred equal-hiring practices in other companies and industries.(3)

|

A Twin Cities railroad porter in 1935. Image Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. |

“Black Pride” held its first festival in 1999,(5) 50 years after African-American individuals were confined to employment in railroad customer service. Indeed, the organization formed 28 years after industrial uses nearly vanished from Minneapolis, and 27 years after the first Twin Cities Pride Festival took place in Loring Park. In 2009—ten years since the first Black Pride Celebration—organizers located the festival on Boom Island, following a church service at the Parkway United Church of Christ.(6)

The event blended an past site of restrictive employment with a present cause for celebration—the Black queer community grows and flowers much as the island does.

(1)Millet, Larry. Twin Cities Then and Now. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1996. Page 15.

(2)Author unknown: "Boom-Nicollet Island Pedestrian Bridge--Full name: Wisconsin Central Railroad Bridge (ca. 1901-present)" http://stanthonymain.com/bridges/NicBoom.php

(3)Taylor, Quintard. "The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle's Central District from 1870 Through the Civil Rights Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994. Page 25.

(4)"Grand openings planned for two riverfront parks." The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, 6/26/1987. http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=MN&p_theme=mn&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&p_topdoc=1&p_text_direct-0=0EFE4921808F6B6E&p_field_direct-0=document_id&p_perpage=10&p_sort=YMD_date:D&s_trackval=GooglePM

(5)Henry, Imani. "Black Gays Celebrate Pride." Worker's World, June 1999. http://www.workers.org/ww/1999/blackpr0610.php

(6)Sanna, James. "Get Ready, Get Set: It's Black Pride!" TheColu.mn, 9/11/2009. http://thecolu.mn/340/get-ready-get-set-its-black-pride

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)