Queer Religious Leaders

Text by Tristan Cabello. Copyright (©) by Tristan Cabello, 2008. All rights reserved.

Clarence Cobbs

Commonly called “Preacher,” Reverend Clarence Cobbs was the leader of the First Church of Deliverance, the most popular church in Bronzeville. While he never publicly revealed or discussed his homosexuality, neither did he hide it. Cobb’s homosexuality was well known within the Bronzeville community: historian Timuel Black claimed that “Cobbs was gay,” adding that “everybody knew about it.”[1] Bronzeville old-timers remember a choir filled with gay men and vacation trips that Cobb would take with his male “assistant;” which led historians such as Wallace Best to claim that Cobb “lived openly, yet silently.” As Pearly Mae noted, the man was “more powerful that Harold Washington,” as “he could bring the votes,” and “politicians always spoke of him favorably.”[2]

The First Church of Deliverance began as a storefront church on State Street. In its early days, Cobbs emphasized religious iconography (candles, incense, robes, sacred objects) in his church and sold “Blessed flowers” promising to bring “good luck.” By the 1940s, the church had more than two thousand members. Historian Wallace Best claims that the church had enough resources to send the Reverend on “an expensive vacation trip” each year, where he took his male secretary, R. Edward Bolden, with him – spreading the rumor that he was gay. Cobbs was a member of the NAACP in Chicago.[3]

Mary Evans

Mary Evans, second pastor of the Cosmopolitan Community Church was rumored to be a lesbian because of her relationship choices. Evans never married but had two long-term relationships with other women. She met Harriet Kelley, her first long-term friend, when she was a young preacher in Indiana. Edan Cook, daughter of William D. Cook, was her long-term friend for the rest of her life. Evans often qualified her as her “sister.”

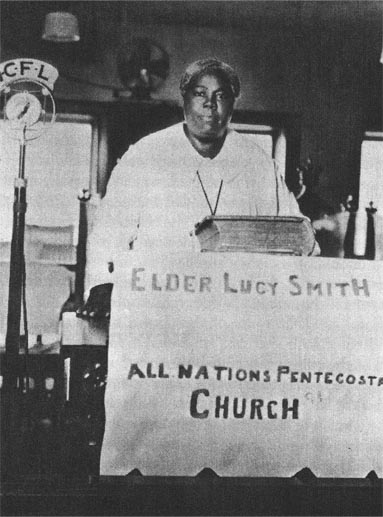

Elder Lucy Smith

Lucy Smith was a symbol of the important role Black women played in Chicago’s religious world. Smith was the “overseer” of an entire “General Conference of Churches” of which her “All Nations Pentecostal Church” was the main church.

Historian Wallace Best noted that several sources from the 1930s characterized Lucy Smith, as well as many other female religious leaders, as “plain,” “buxom,” “plump and brown,” or “homely,” commenting on their “deep voices.” Samuel Strong concluded that “women preachers were somewhat mannish, overweight, and hoarse, and usually lesbian.”

NEXT: Gay life in 1940's Bronzeville: The Story of "Nancy Kelly"

- ↑ Timuel Black, as quoted in Wallace D. Best, Passionately Divine, No Less Human: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago 1915-1952 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005) 205

- ↑ “Interview with Pearly Mae,” in Sukie de la Croix, “Black Pearls,” BlackLines, February 1999, 26.

- ↑ Wallace D. Best, Passionately Divine, No Less Human: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago 1915-1952 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005)