Third-Gender Roles in Indiana-Area Native Americans

Native American Cultures and White LGBT Identities

The racial history of Indiana contributes to a complicated politics of cultural identification for white LGBT people living there now, who often feel sympathy for displaced native cultures, identify with them as members of another oppressed social group, and celebrate aspects of those cultures that resonate with ways that contemporary LGBT communities think about their own identities and sexualities. It has been especially common for contemporary LGBT people to be fascinated by, and to romanticize, native cultural practices variously labeled as “berdache,” “two-spirit,” “third-gender,” “gay Indian,” or “transgender native.” Although it is presumptuous to label Native American cultural phenomena using purely Western terminology, it is nevertheless true that certain Native practices and statuses superficially resemble modern queer identities.

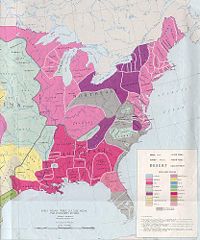

Indigenous Peoples of Contemporary Indiana

Although our research has not yet turned up information on whether the Shawnee people had categories of sex, sexuality, gender, and identity that didn’t easily correspond to dominant Eurocentric notions of “man” and

“woman,” several other tribes of the Midwest certainly did. The Miami had a status known as “Waupeengwoatar,” (White Face); the Potawatomi had “M'netokwe,” (a masculine name with a feminine suffix), and the Illini had “Ikoneta.” This role was closely associated with the “Manitou,” or ancestor spirits, and it was restricted to male-bodied individuals. Those in the role were ineligible for status within the male hierarchy but could win recognition in the female hierarchy, and they spoke in the language inflection reserved for women. The Chippewa, who were closely related to the Illinois, had a third-gender role for male-bodied individuals called “Egwakwe,” and a gendering system that divided the objects in the world, including people, into active or passive categories, without reference to a person’s genital status. The Iroquois also had a third-gender role, and a system of leadership that ensured that women had a relatively large amount of power in making decisions compared to European colonists and other Midwestern tribes.

Not all Native American tribes had “third-gender” social positions to be filled. Many instead had a simple male/female dichotomy similar to the dominant Western gender system, and one should take care to remember that even those peoples whose cultural had identity options we’d now be tempted to label “progressive” were still generally dominated by male-bodied individuals filling a male-typical role. The Iroquois, for example, in spite of having a third-gender role and privileging women’s votes for leaders, segregated social roles by sex, and restricted most leadership positions to men. Furthermore, even when cultures had a third-gender roles, members of those cultures sometimes expressed ambivalence about the individuals who occupied them. One well-known account involves a female-bodied/third-gender Lakota individual who was killed by fellow tribesmembers after taking female lovers in violation of the social norms for that role.

Imperialism and Extermination

Although some of these identities remain part of contemporary native cultures, European colonization and Manifest Destiny have drastically diminished them in both cultural memory and current practice. The third-gender status among the Illinois, for example, was widely observed by French merchants in 1675, but had virtually disappeared by 1698, due largely to the influence of Catholic missionaries. Other tribes in the region similarly found themselves pressured to suppress such cultural traits as European colonization increasingly saturated Native American life.

Appropriation

While it would be inappropriate to place Native American identities in the spectrum of modern Western queer identities, it remains difficult for many North Americans with solidly European family histories to avoid drawing suggestive parallels between the two. Although there is virtually no direct continuity between indigenous forms of sexuality/gender and the white settler society’s queer identities, native “third-gender” statuses nevertheless inspire many to envision an alternative social order in which queer and straight could be harmoniously integrated, and in which the sad history cultural contact in North America had happened differently.