Ernest Burgess: Exploring Sexual Systems

Sexual Systems

Many historians have analyzed the different “sexual systems” competing at the beginning of the twentieth century. In Gay New York, Historian George Chauncey argues that adherence to normative gender roles, more than the choice of actual female sexual partners, was the practice from which men derived their sense of masculine integrity during this period. Referring to the fairies and “pansies” who populated the streets of New York’s working class in the first decades of the century, Chauncey claimed:

"The determinative criterion in the identification of men as fairies was not the extent of their same sex desire or activity, but rather the gender persona and status they assumed. It was only the men who assumed the sexual and other cultural roles ascribed to women who identified themselves and were identified by others as fairies… The fundamental division of male sexual actors, then, was not between “heterosexual” and “Homosexual” men, but between conventionally masculine males, who were regarded as men, and effeminate males, known as fairies or pansies, who were regarded as men as virtual women, or, more precisely, as members of a third sex that combined element of the male and female." [1]

From One Sexual System to the Other

Chauncey claimed also that “the transition from one sexual regime to the next was an uneven process,” appearing first in the middle class and then “in much of European-American and African-American working class culture” - the transition from the system based on gender identities to the system opposing homosexual and heterosexual identities was not achieved until the mid-twentieth century. [2] Situated between these two sexual systems, Chicago’s South Side queer population illustrated the dynamics and tensions of the transition process, allowing queer individuals and varied sexual desires to express themselves, and often to compete. In the South Side’s Black neighborhood, the transition between these two classifications did not follow a linear progression; the creation of new identities and sexual desires was intertwined with racial and class identities.

Professor Ernest Burgess and South Side Queers

University of Chicago Sociology Professor Ernest Burgess encouraged his students to use the resources of the culturally diverse city of Chicago. Many of his graduate students’ research projects throughout the 1930s incorporated homosexuals into their analyses of urban life.[3] Student papers described frequent, casual encounters with African American gay men in the city. By the 1930s, Black gay men had become a fixture of Chicago urban life and a legitimate subject for sociology research.[4]

Homosexual Identities on the South Side

Homosexual identities on Chicago’s South Side usually revolved around gender identity. In an interview with a University of Chicago sociologist, Leo, a Black homosexual, reported having read that “men who desired men were often effeminate.” When introduced to Chicago’s queer world, he claimed to have seen “boys dance together,” calling each other “husband and wife” and several of them were “arguing about men.” The terms that Leo used to describe homosexuals – “Sissy” or “Nelly” - also described gender characteristics. This mix of gender identities crossed sexual orientations, often creating confusion. For example, Chicago journalist Frank Davis noted that female impersonator Mae West confused her fans because her feminine accessories did not allow one to forget her body built like a “boxer or football player.” Moreover, “although Barrows repeatedly had a weakness for men,” Davis added that he engaged in sexual relations with “a very sexy German girl.” In a similar tone, Clarenz, a female impersonator at 101 Ranch, married Alberta Anderson. This confusion between sexual and gender identities confirms the tensions between the two competing systems. For some, gender identity was independent from sexual orientations, and for others they were connected.

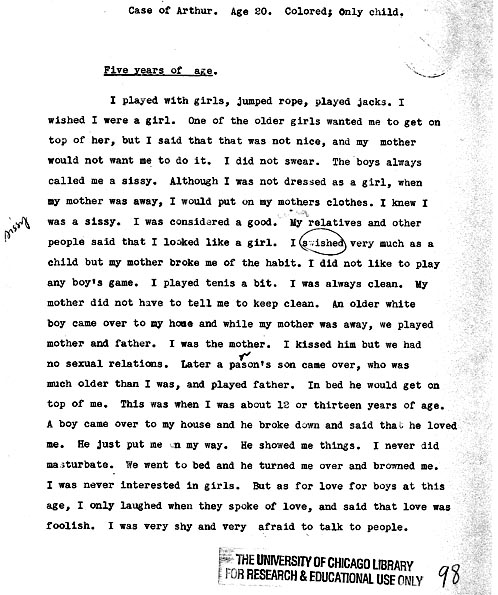

Arthur, 20, Negro

Other young African American gay males interviewed by Ernest Burgess and his students confirmed that their identity was deeply grounded in gender identities. Arthur, 20, African-American, remembered that he “played with girls, jumped rope, played jacks” and “wished [he] were a girl.”

“The boys always called ma a sissy. Although I was not dressed as a girl, when my mother was away, I would put on my mothers clothes. My relatives and other people said that I looked like a girl. I swished very much as a child by my mother broke me of the habit. Later when I was about 18 years of age, I met Egan. He was my husband. We lived together for two years, and he gave me a marriage ring. I really loved him. I knew Egan was crazy about woman but that did not bother me. I knew that he was cheating.”

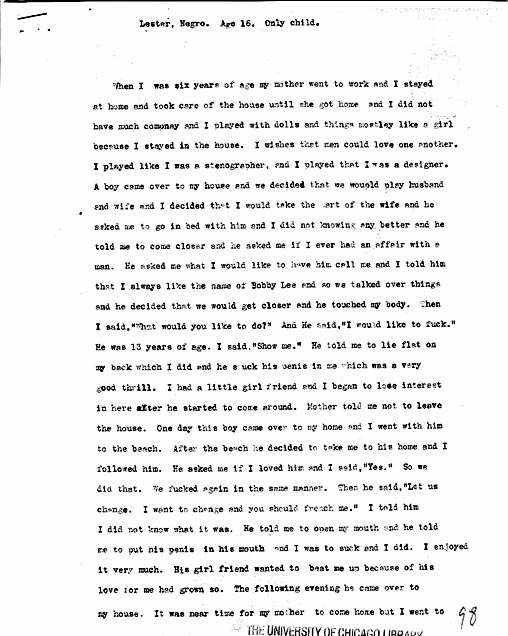

Lester, 16, Negro

Lester, 16, recalled he “would walk down the street in [his mother’s] clothes and the boys would say “what a sissy!”

“I would get mad and would say: “I am not a sissy!” I am just a boy that likes to wear women’s clothes.” It made me very mad.”

The Story of Walt Lewis

Walt Lewis claimed that he “cannot tell from a woman if they never have whiskers or mustache, they take it in the ass, French you, like to be called girls names, and […] let you stay with them like a man and wife”

“When they want to get married they go to a bull daggard ball, a bulldaggers marries them, put a mark oor the fag, and they tells her next husband how many times she has been married. […] The women fucker, she fucks women like men, if she fucks your wife or girl will you cannot fuck good enough for her she will leave you are quit right away. The fags like to be fucked in the ass, just like when you fuck a omwne.

Leo, 18, Negro

Leo, 18, “I decided that I could act as I wished among the faggots, but among the straight people I had to act reserve. I have always swished quite a bit, and with Jam people I tried to act more manly but I was conscious of myself with Jam people. I was always afraid that I would do something out of the way, and when I was with the faggots for about a month, I decided I would go mostly with the faggots”

- ↑ George Chauncey, Gay New York (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 49.

- ↑ George Chauncey, Gay New York, 49.

- ↑ On Burgess methodology, see T.V. Smith and Leonard D White, eds, Chicago: An experiment in Social Science Research (New York: Greenwood Press, 1968) and Robert E. L Faris, Chciago Sociology 1920-1932 )San Francisco: Chandler Publishing, 1967)

- ↑ Pauline Redmond, “term paper for Social pathology,” Folder 7, Box 148, Burgess Papers; “Sociology 270 Exam,” February 1938, folder 10, box 145, Burgess Collection.