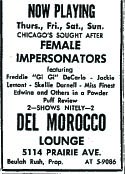

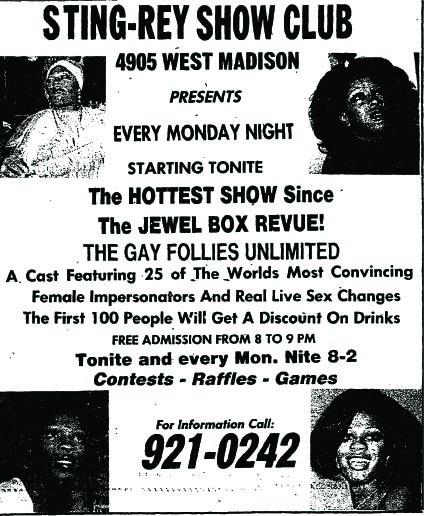

Female Impersonators

The Drag Balls

Female impersonators enjoyed a great popularity due to the “Drag Balls” organized every Halloween and New Year’s Eve. The nation’s first drag balls took place during the last decades of the nineteenth century and from their inception their appeal transcended racial lines. [1]

Two of the earliest documented balls reportedly took place in DC and New York City, and were, according to one account, attended exclusively by black gay transvestites. In 1893, Dr. Charles H Hughes of St Louis described the Washington Drag Dance with these remarks:

In this stable performance of sexual perversion all of these men are lasciviously dressed in womanly attire, short sleeves, low necked dresses and the usual ball room decorations and ornaments of women, feathered and rib boned headdresses, garters, frills, flowers, ruffles, etc… and deport themselves as women. Standing or seated on a pedestal, but accessible to all the rest is the naked queen (a male), whole phallic member, decorated with a ribbon, is subject to the gaze and osculation in turn, of all the members of this lecherous gang of sexual perverts and phallic fornicators. [2]

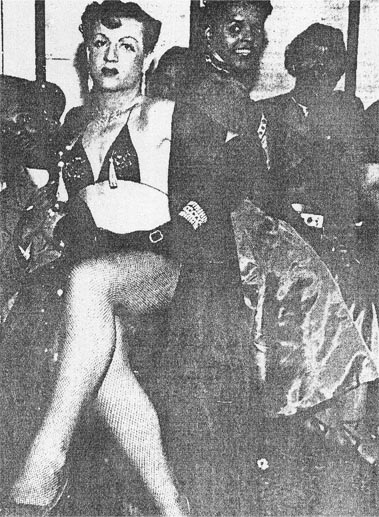

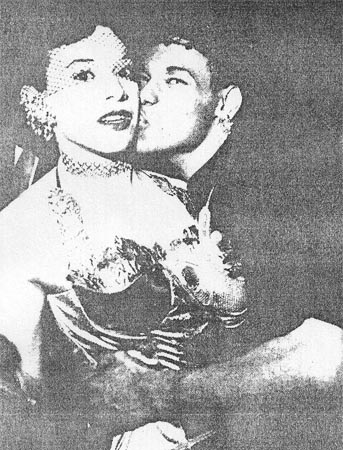

Petite Swanson and Valda Gray

“Petite Swanson,” a member of Valda Gray's troupe of female impersonators, was one of the numerous Afro-Homos who took advantage of the performance of her identity. Swanson had made a name for herself in Chicago, where she did not hide her ambitions to “become a star." When Billboard announced in 1937 that Swanson had just been signed to the Sunbeam label, it put her on the road to fame. Yet she never compromised her identity as a female impersonator as the author of the Billboard article acknowledged that Swanson was “a fem impersonator whose real name (was) Alphonso Horsley.”

By clearly embracing her transgender identity (Marl Young, Sunbeam’s owner, printed Swanson's real name right on the record label), Swanson and many other drag queens who lived comfortably thanks to the night-lounge business and entertainment. During the Depression, professional drag entertainers like Lorenzo Banyard and Jacques Cristion indeed stood out thanks to their relatively well-paying jobs, which often enabled them to provide for their families’ needs.

At Joe’s Deluxe, female impersonators would be paid “$50 for a seven-day week and were assured of steady year-round work.” Lorenzo Banyard could earn up to forty dollars a night as a club dancer, compared to the twelve dollars a week he brought home from his job as a dishwasher at the Wabash YMCA.

In Bronzeville, female impersonators were very respected as entertainers. Theodore Jones, for instance, hired Valda Gray’s troupe for an “honoring party” in October of 1938 and the Chicago Defender often cited them in articles, as legitimate entertainers beside musicians or dancers. The rare appearance of female impersonators in White newspapers was often satirical or derogatory. [3]

Homosexual Identities and Female Impersonators

Homosexual identities on Chicago’s South Side usually revolved around gender identity. In an interview with a University of Chicago sociologist, Leo, a Black homosexual, reported having read that “men who desired men were often effeminate.” When introduced to Chicago’s queer world, he claimed to have seen “boys dance together,” calling each other “husband and wife” and several of them were “arguing about men.” The terms that Leo used to describe homosexuals – “Sissy” or “Nelly” - also described gender characteristics. [4]

This mix of gender identities crossed sexual orientations, often creating confusion. For example, Chicago journalist Frank Davis noted that female impersonator Mae West confused her fans because her feminine accessories did not allow one to forget her body built like a “boxer or football player.” Moreover, “although Barrows repeatedly had a weakness for men,” Davis added that he engaged in sexual relations with “a very sexy German girl.” In a similar tone, Clarenz, a female impersonator at 101 Ranch, married Alberta Anderson. This confusion between sexual and gender identities confirms the tensions between the two competing systems. For some, gender identity was independent from sexual orientations, and for others they were connected.

Working-class Black men shifted rather freely between sexual relations with women and men. For this reason, female impersonators at “Drag Balls” or cabarets were often their favorite targets. Female impersonator “Nancy Kelly” remembers the first Drag Queen that he had seen, Joanne, was so popular that Black men would gather to “whistle” at the corner of 31st Street and State Street. [5]

If these men mocked Joanne because she “stood on the corner with her hand on her hip, her hair drawn back into the ponytail,” Nancy notes that “they were not bothering her.” They indeed simply wanted to “do her,” according to the female impersonator. Like the journalists who covered these events, these men often adopted an attitude of male superiority toward the female impersonators.[6]

These demonstrations of masculinity allowed these heterosexual men to transform these effeminate men into real women, somehow normalizing their role as sexual partners. At times, these men went so far as to explicitly state the sexual favors they hoped to receive from these female impersonators or effeminate men. In this way, Leo claimed he had encountered these effeminate men and that he “would like to have th[ese] bitch[es] for [him]self,” going as far as stating that he “wanted to fuck [them].” In labeling his sexual partners “Bitches,” Leo did not only make reference to their effeminate mannerisms but also reinforced the idea that these partners were virtually women.[7]

- ↑ "GRAND MASQUE BALL :Attend the Second Annual Jollification of the North Shore Men's Club at Phoenix Hall, Sedgwick and Division Street," The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966), November 30, 1912; "Mask Dance at Masonic Hall." The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966), February 23, 1918; "NORTH SHORE DANCING CLASS," The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966), February 16, 1918; "THE DOUGLASS," The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967), May 31, 1924; "The Monogram," The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966), August 2, 1913; "The Monogram," The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966), December 23, 1911; "WEBER'S THEATRE :19th and Wabash Ave," The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966), February 18, 1911.

- ↑ Charles H Hughes, as quoted in Katz, Gay American History, op. cit., 42-43

- ↑ on “Petite Swanson,” see M.W. Stearns, “Dallas Bartley Pleases Those in Search of Jazz,” Down Beat, September 15, 1945, 2 and “Female Impersonators: Unique Chicago Night Club Features make-believe Ladies as Entertainers,” Ebony, March 1948, 59-63

- ↑ “Life history materials on Leo”, Burgess Collection, Box 98, Folder 11, The University of Chicago, Special Collection Center, Chicago, IL

- ↑ Nancy Kelly, Interview by Allen Drexel

- ↑ Nancy Kelly, Interview by Allen Drexel

- ↑ v “Life history materials on Leo”, op. cit.