Third-Gender Roles in Indiana-Area Native Americans

Though it is presumptuous to attempt label Native American cultural phenomena using purely Western terminology, it is clear to the observant historian that certain Native identities resemble, at least on the surface, modern queer identities. Though it would, again, be presumptuous to say that such identities really exist on the Western queer identity spectrum, it is difficult to avoid drawing parallels and making some level of identification, even for North Americans with solidly European family histories.

Unfortunately, the violent imperialism of European colonization and, later, all-American Manifest Destiny have largely erased these identities from history. Some records and research, however, have begun to uncover the histories of these social positions that demonstrate the paths that might have been taken had Europe itself…happened differently.

Tribes of the Midwest

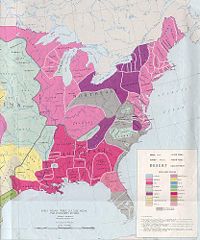

Several tribes of the Midwest had third-gender roles or non-western conceptions of gender.

The Iroquois, who covered much of modern Indiana prior to European colonization, had a third-gender role and a system of leadership that ensured that women had a relatively large amount of power in making decisions, compared to European colonists and other local tribes. The Illinois had a third-gender role closely associated with the term manitou (itself a word referring to spirits or ancestors) restricted to male-bodied individuals. Those in the role were ineligible for status within the male hierarchy but could win recognition in the female hierarchy and spoke with the language inflection reserved for women.

The Chippewa had a third-gender role for male-bodied individuals called egwakwe, and a gendering system dissimilar to European models, which divided the objects in the world as possessed of either active or passive force. These categories did not easily relate to European male and female categories, transcending genital sex as the best (or even an important) determinant of one’s role.

Not all Native American tribes had “third-gender” social positions to be filled. Many instead had the familiar Western male/female dichotomy, and one should take care to remember that even those possessed of what we might call “progressive” identity options and categories today were still generally dominated by male-bodied individuals filling a male-typical role. The Iroquois, who had a third-gender role and who privileged women’s votes for leaders, still restricted most leadership positions to men (in fact most positions were sex-segregated, and more positions were male-only than were female-only), for example.

Likewise, Native American tribes were not always entirely friendly to those occupying third-gender roles. There is a well-known account of a female-bodied Lakota individual occupying a third-gender role who was killed by fellow tribesmen after taking female lovers, including several recorded homophobic statements made about the individual killed.

Imperialism, Colonization, and the Eradication of Native Cultures

Obviously most Native American culture did not survive into the 20th century. Some aspects of Native cultures, however, especially those particularly repugnant to European thought, hardly survived first contact.

For the Illinois tribe, for example, the third-gender identity, which was well-established ca. 1675, all but disappeared by 1698, in a pattern tied strongly to Illinois exposure to European missionaries. Other tribes with similar non-European gender or sexual roles increasingly found themselves pressured to put an end to such cultural traits as trade with and missionaries from European colonies increasingly saturated Native American life.

Patrick Califia, Sex Changes: the Politics of Transgenderism. Cleis Press, 2003. Raymond E. Hauser, “The Berdache and the Illinois Indian Tribe during the Last Half of the Seventeenth Century.” Ethnohistory 37 (1990): 45 Beatrice Medicine, “Directions in Gender Research in American Indian Societies: Two Spirits and Other Categories,” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. April 2009. http://orpc.iaccp.org/index .php?option=com_content&view=article&id=61%3Abeatrice-medicine&catid=7%3Achapter& Itemid=4 . Katsithawi Thomas, “Gender Roles among the Iroquois,” Vanier College’s The Native Circle, http://ww w.vaniercollege.qc.ca/tlc/publications/native-circle/native-circle-2003/ashley-thomas3.pdf.