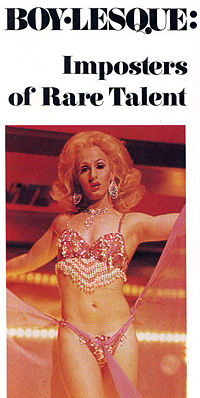

Boylesque

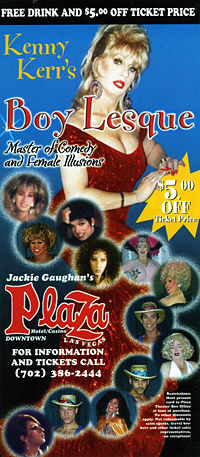

Kenny Kerr and Boylesque

(c)Dennis McBride, 2009

Las Vegas and Female Impersonation

Female impersonation has always lurked at the edge of Las Vegas entertainment culture. Famed impersonator Billy Richards played the Fremont Tavern and the Green Shack in the 1930s, while Gordon Stafford and Francis Russell performed at the notorious Kit Kat Club during World War II. Beginning in the 1950s, such stars as T. C. Jones, Lynne Carter, Jim Bailey, and Craig Russell all brought their revues to Las Vegas. None of these shows, however, played longer than two or three weeks, or became part of Las Vegas entertainment tradition in the way that Lido de Paris, Folies Bergere or Bottoms Up! did.[1]

Kenny Kerr and This is Boy-Lesque

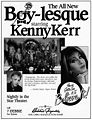

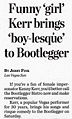

Until Friday, May 13, 1977 when Kenny Kerr debuted This Is Boy-Lesque at the Silver Slipper’s Gaiety Theatre. Boylesque was different from any of the impersonation revues that had gone through Las Vegas before. The show combined classic impersonation similar to the elegant acts performed by Lynne Carter and Jim Bailey with the kind of dancing, singing, comedy revue Las Vegas producers adored. While the variety of celebrity female impersonators, flashy costumes, and energetic choreography dazzled audiences, it was always Kerr himself who brought those audiences back. Kerr’s routines were not scripted, his repartee was ad-libbed and genuinely funny. Kerr himself sang rather than lip-synching. His ability to put audiences at ease and create an intimate venue out of an ordinary showroom made Boylesque one of the most popular shows in Las Vegas history.[2]

Female impersonator vs "male actress"

Despite the success of his show, Kerr remained closeted. Kerr referred to himself as a "male actress" not a female impersonator, and as late as 1982 insisted in a Las Vegas Review-Journal interview with A. D. Hopkins that he had "a girlfriend and hopes she will have his child next year." This attitude initially distanced Kerr from the gay community. The 1970s-80s was still the dark ages for gay people in Las Vegas, particularly in the city's gaming and entertainment industries. No one with a criminal record could work in those businesses then—nor could those businesses cater to criminals. Nevada's sodomy law was enforced so that Kerr, and all other gay entertainers and gaming personnel in Las Vegas were de facto criminals. Add common bigotry to the mix and gay people in the business had to be closeted (read a 1991 eyewitness account of Boylesque).[3]

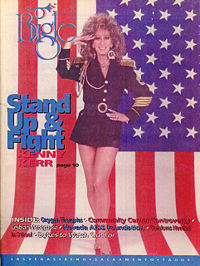

Kenny Kerr in the Community

Despite his rocky start, in time Kerr became one of the Las Vegas gay community's most dependable and outspoken supporters donating his time, talent, and money to community causes. He performed in fundraising benefits for Aid for AIDS of Nevada [AFAN], Golden Rainbow, Lighthouse Compassionate Care, and the Gay and Lesbian Community Center. His $1,000 donation to Nevadans for Constitutional Equality toward the repeal of Nevada's sodomy law in 1993 was the single largest contribution, and Kerr was always available to perform, emcee, or judge at a variety of gay community events, no matter how small. To support gay men and women in the military and protest the government's homophobic "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy, Kerr debuted an "Uncle Sam Wants Everyone" number in his show complete with a World War II-style poster of Kerr standing at attention in military drag. In 1997 Kerr received the gay community's Lifetime Achievement Award at the Gay and Lesbian Community Center's Honorarium.[4]

Even before he was accepted into the Las Vegas gay community, Kerr was embraced by Las Vegas's straight business and entertainment establishment. This acceptance was reinforced by Kerr's support of local charities such as Child Haven, the Cancer Society, and the Injured Policemen's Fund, as well as by his loyal heterosexual fan base. Kerr's involvement in these circles raised the gay community's profile and by embracing Kerr, that establishment recognized and began accepting Las Vegas's gay community.[5]

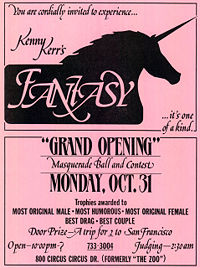

When the Silver Slipper was sold in 1988, Kerr moved to the Sahara, and over the next two decades bounced among several Las Vegas hotels including the Stardust, the Union Plaza, the Debbie Reynolds Hotel Casino, the Frontier, the Orleans, the Suncoast, and the Sunset Station in Henderson, Nevada. Along the way Kerr has dealt with embezzling employees, bankruptcy, a still-born talk show venture called Vegas Nights, a failed bar called Kenny Kerr’s Fantasy, and, in 1997 a near-miss business involvement with Torsten Reineck, owner of the Apollo bath house in Las Vegas, who was later associated with serial killer Andrew Cunanan who murdered fashion designer Gianni Versace.[6]

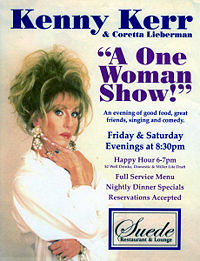

At the time of this writing Kerr has still not found a venue to call home in the way the Silver Slipper once was for him. He travels in and out of the country performing in bistros, cabarets, cruise ships, hotels and showrooms elsewhere—but mainly splitting his time between Las Vegas and Palm Springs. He looks back on his 30+ roller-coaster years in Vegas with equanimity.[7]

"I've been fucked over by people I never thought would fuck me over," Kerr says. "I'm a survivor. I'm the best in the business at what I do. There's no more Charles Pierce. There's no more Lynne Carter. Jim Bailey's burnt out. My career can go forever because I create my own character and I'd rather be a first-rate me than a second-rate someone else. I think I've done a lot for the community, gay and straight. I believe the respect you get while you're on stage, you can demand, but I think the respect you get off stage, you must earn. And I feel I've earned it."

Image Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Las Vegas Review-Journal (August 18, 1938), 2; (September 14, 1938), 2; (March 23, 1943), 4; (June 26, 19.44), 6; (November 5, 1953), 17; Fabulous Las Vegas (November 7, 1953), 12, 19, 33; (October 16, 1971), 22, 26; Panorama (July 17, 1970), 11; (February 12, 1971), 3, 12; (October 8, 1971), 12; (May 17, 1974), 13; (May 24, 1974), 42; Out Las Vegas Bugle (October 11, 2002), 31; Kenny Kerr, interview by Dennis McBride, May 29-30, 2001 [author’s transcript]; Tony Midnight, interview by Dennis McBride, August 29, 2000 [author’s transcript]; Hanford Searl, interview by Dennis McBride, November 2, 1996 [University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Lied Library Special Collections Department (hereafter noted as UNLS) transcript HQ76.2 U52 N37 1997].

- ↑ Las Vegas Review-Journal (May 13, 1977), 32, 34; Panorama (May 13, 1977), 76; Las Vegas Sun (May 15, 1977), 12; Las Vegas Star (August 1977), 12-13, 38; Kerr interview.

- ↑ Las Vegas Sun (February 4, 1979), 1C, 5C; Vegas Gay Times (March 1979), 2; Las Vegas Review-Journal (March 6, 1978), 3A; (July 23, 1978), 5A; Las Vegas Review-Journal "Nevadan" (April 11, 1982), 13L; Clark County Code of Ordinances 1973, Title 8 (Liquor and Gaming Licenses and Regulations), chapter 8.08 (Liquor and Gaming Licensing Board Policy and Procedures), §030(c) (Grounds for Disciplinary Action) [while earlier versions of the county code specifically named homosexuals as cause for loss of a liquor and gaming license, the code at the time of this writing (2009), Title 8, Chapter 8.20, §570(f) makes no such reference].

- ↑ Bohemian Bugle (October 1987), 1; Las Vegas Bugle (May 1991), 1, 6; (July/August 1993), 10-12, 21; (November/December 1995), 44; (April 1996), insert, and 16; (January/February 1997), 4, 61; (June/July 1997), 20, 22-24; (December 1997/January 1998), 54, 56; (October 8, 1999), 31; (March 1, 2002), 4; (March 15, 2002), 32; Night Beat (August 2004), 6, 13, 3; (October 2004), 17; Q Tribe (July 1997), 3, 5; (December 1997), 2, 9; Out Las Vegas (November 2001), 9; (March 2002), 8; (April 2002), 13; Las Vegas Review-Journal (July 21, 1993), 1B, 4B; Las Vegas Sun (July 21, 1993), 1A, 8A.

- ↑ Kerr interview.

- ↑ Nevada Gay Times (January 1984), 10; (February 1984), 7; (March 1984), 14; (June 1984), 17; Las Vegas Sun Showbiz Magazine (August 7, 1988), 24; Las Vegas Sun (December 11, 1989), 8D; (December 10, 1990), 11D; (March 29, 1991), 7D; (April 5, 1991), 1D; (September 17, 1991), 6C; (January 24, 1992), 5D; (August 12, 1992), 2C; (September 4, 1998), 2C; (October 19, 1999), 3C; (September 22, 2000), 2C; (February 23, 2001), 3E; (July 15, 2004), 1E-2E; Las Vegas Review-Journal (April 1, 1990), 1D; (March 10, 1991), 2A; (September 11, 1998), 4J; September 30, 2000), 3B; Las Vegas Review-Journal/Las Vegas Sun (September 15, 1991), 3J; (August 16, 1998), 1J; (October 15, 2000), 6J; (March 4, 2001), 6D; (May 20, 2001), 1J; Las Vegas Bugle (September 1992), 14; (September/October 1993), 19, 21; (July/August 1995), 51; (November/December 1995), 40-42, 47, 54-55; (November/December 1996), 68; (September/October 1997), 30, 32-33; (August 18, 2000), 31; (December 8, 2000), 32; (January 5, 2001), 31, 37; (January 19, 2001), 35; (February 2, 2001), 36; (June 22, 2001), 39; Las Vegas Bugle Digest (February 7, 1997), 19; Night Beat (October/November 1995), 4; (August 2004), cover, and 6, 28-29; What’s On [in Las Vegas] (May 20, 1997), 44-45; Out Las Vegas (September 1998), 4; (June 2001), 16, 34; (August 2001), 43; Out Las Vegas Bugle (July 19, 2002), 42; Best Read Guide Las Vegas (November 2000), 37; Lesbian Voice (July 2001), 2; Las Vegas Review-Journal Southeast View (July 7, 2004), 2AA; Las Vegas Mercury (July 8, 2004), 9; Kerr interview.

- ↑ Out Las Vegas Bugle (August 30, 2002), 53; (September 13, 2002), 36, 47, 52; (September 27, 2002), 47; (October 11, 2002), 31, 47; (November 22, 2002), 8, 46;(December 6, 2002), 8; (December 20, 2002), 36; Bay Area Reporter (February 27, 2003), 27; Q Vegas (June 2004), 18; Las Vegas Sun (July 15, 2004), 1E-2E; Kerr interview.