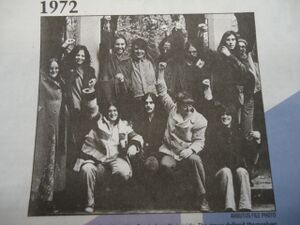

Gay Liberation Front in Bloomington

Bloomington Gay Liberation Front (GLF), like many similar groups sprouting up on college campuses across the country, took shape in response to the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City. The first known gay group in southern Indiana, it began organizing in the spring of 1970, and held its initial public meeting in August of that year. By proclaiming themselves to be part of a Gay Liberation Front, Bloomington gay and lesbian activists clearly expressed their sense that they were the local representatives of a burgeoning national movement.

Early Organizing

Like other chapters of the loose-knit affiliation, Bloomington GLF was organized according to New Left principles that sought to promote participatory democracy; it therefore had no elected officers, formal structures of governance, nor clearly-defined membership. Although the group’s name referenced the language of gay revolution and Third-World solidarity that permeated the gay liberation movement nationwide, Bloomington

GLF was never a radical group. Rather, the group’s political philosophy reflected a belief that tactics and strategies for social change that might be more attuned to urban environments were not well suited to their local situation. As a result, Bloomington GLF’s focus from the outset lay in fostering a “Gay is Good” sense of homosexual pride—albeit in sometimes militant or confrontational ways. It embraced a minoritizing view of homosexual identity, rather than advancing a more overarching critique of sexuality-based and gender-based oppressions and their links to other structural forms of oppression.

During the time immediately following its formation, the BGLF often drew more than one hundred students, but attendance dropped drastically over time to only around twenty regular attendees. Many members attributed the drop in attendance to the leftist political leanings of the group, which alienated Bloomington’s more conservative student body. This tension may have ultimately lead to the group’s transformation into the Bloomington Gay Alliance, and then the Bloomington Gay and Lesbian Alliance.

Events, Projects, and Activism

Regular BGLF activities included bi-weekly meetings to conduct organizational business that often drew more than a hundred attendees, weekly information tabling on the IU campus to promote gay visibility and provide information about homosexuality, as well as hosting various consciousness-raising and support groups. Bloomington GLF also sponsored several wildly successful dances that drew people from throughout the region; held in the Indiana Memorial Union’s 800-person-capacity Alumni Hall, the dances usually sold out. The dances generated most of the Bloomington GLF’s operating funds, enough to rent office space in the Indiana Memorial Union.

Community Engagement and Fighting Discrimination

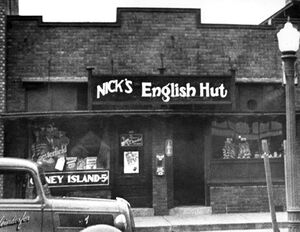

One of the first Bloomington GLF protest actions took place in late July 1971. It responded to a sign posted in Nick’s English Hut—a bar and restaurant popular with gay students near the Indiana University campus—that read, “This is not a fruit stand.” When confronted over the meaning of the sign, the management stated that it meant “exactly what you think it means,” and escorted the inquiring students off the premises.

The following night, 23 July 1971, Bloomington GLF formed an informational picket line outside the bar and distributed mimeographed pamphlets encouraging patrons to take their business elsewhere. The sign was removed the following day. Like more dramatic protests in other cities, Bloomington GLF’s protest at Nick’s English Hut asserted gay people’s fundamental right of public assembly, free from harassment and discrimination.

Divisions and Exclusions

The Bloomington GLF was overwhelming white and male. Within the group’s first year a semi-autonomous women’s caucus known as the Gay Women Liberation Front formed over frustration with the perceived sexism of male-dominated meetings, and later became the more separatist Lesbian Liberation Front. The women’s groups, in keeping with the ethos that “the personal is political,” concentrated their liberation struggles on mutual support and consciousness-raising.

There was very little participation by people of color in any of these groups. One active member of Bloomington GLF acknowledged that “there was certainly racism,” noting, “this was after all Bloomington, Indiana.”

Unlike New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco in the early 1970s, where gay liberation and lesbian feminist organizations pointedly excluded trans- and drag-identified individuals who either had some connection to “old gay” life or some involvement in New Left politics, there is no surviving indication that gender-variant people were ever involved in Bloomington GLF at all, or that the divisive conflicts over gender identity and embodiment that roiled larger communities were even on the radar screen in Bloomington.

Changing Focus

After the initial burst of enthusiasm that greeted Bloomington GLF in 1970, active involvement in the political meetings rapidly dwindled until only twenty or so core activists remained by 1971. Participatory democracy was deemphasized, and in the group’s second year it began electing male and female co-officers.

Activities increasingly focused on simply maintaining an organizational presence on the IU campus, to provide a point of contact for gay and lesbian students. Some early Bloomington GLF participants attributed the drastic decline in attendance to the group’s leftist orientation, which alienated much of Bloomington’s more socially conservative gay and lesbian population. One woman, looking back on Bloomington GLF’s founding a mere three years after the fact, observed, “At that time members were into the whole leftist movement. Now we just have conservative, moderate capitalists like everybody else.”

Successor Groups

In 1973, in a shift replicated in many other locations, Bloomington GLF was supplanted by the Bloomington Gay Alliance (BGA; later the Bloomington Gay and Lesbian Alliance, or BLGA). The new group moved sharply away from leftist politics, and toward providing community support and social services, as well as offering opportunities for socializing. For many participants in BGA, the principal draw of Bloomington GLF had never been political. As early member Duncan Mitchell noted, “Most people were mainly interested in getting laid, finding friends, finding boyfriends, having some place to go on Saturday nights—and that’s important, too, especially considering the relative isolation that gay kids grow up in,” in Indiana.

Interview with Duncan Mitchel, an original member of the Bloomington GLF

Navigation | Home | Before Stonewall | Stonewall to AIDS: the 70s |

AIDS and Community Life: the 80s | The Queer Decade: the 90s | Queer Here and Now: 2001-Present

Sources:

Clark, Susan Elaine. “Gays no longer feel militancy will change public’s attitudes,” Indiana Daily Student, December 5, 1973.

"Gays protest sign in bar," Indiana Daily Student, July 26, 1971.

Mitchel, Duncan. Interview by Julia Turner, Wells Library, Indiana University, November 14, 2009.

Stafford, Harold. "The Libs," Indiana Daily Student (Bloomington), June 8, 1971.

Stafford, Harold. "Gay Liberation: Political Focus Changing," Indiana Daily Student, August 30, 1972.

Navigation | Home | Before Stonewall | Stonewall to AIDS: the 70s |

AIDS and Community Life: the 80s | The Queer Decade: the 90s | Queer Here and Now: 2001-Present

<comments />