Old Minneapolis Courthouse/City Hall

Between 4th and 5th Streets, 3rd and 4th Avenues, Minneapolis, MN

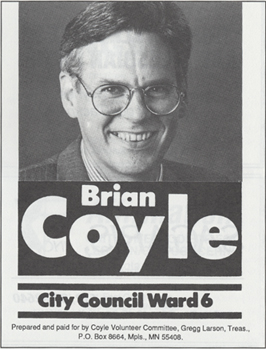

Brian Coyle campaign ad from the 1990 Twin Cities Pride Guide. Courtesy of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection. |

One can argue that City Hall’s construction set a series of events in motion that caused the formation of Minneapolis’ contemporary gay community. For most of the 19th century, officials worked in a tiny wedge-shaped structured at the junction of Nicollet Avenue and Hennepin Avenue in “Bridge Square.” Public servants demanded more space in the 1890s—the Minneapolis City Council chose a new site for a “Municipal Building,” and left its old neighborhood to languish without direct police attention.(1) Bridge Square fell into serious disrepute, and it became a target of urban renewal in the 1910s, when the Gateway District was born.(2)

|

Queer politics developed alongside cohesive “gay” and “lesbian” identities in the early 1970s. Radical organizations such as F.R.E.E. approached the Police Department and conducted training sessions.(5) By 1980, the Gay and Lesbian communities exerted a political voice that had to be contended with.

This backdrop of activism provided Brian Coyle with the necessary clout to obtain a seat on the Minneapolis City Council in 1983—a few years before, he organized Minnesotans Against the Downtown Dome (MADD), which opposed construction of the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome.(6) The openly-gay Councilman was immediately a public spokesperson for the queer community as the HIV/AIDS nightmare unfolded in the 1980s. He announced that he was HIV+ in 1991 and died shortly thereafter.(7)

Coyle predicted that voters would appoint more queer politicians as the years progressed. Time proved this prediction to be a premonition—presently, councilmemebers Gary Schiff and Robert Lilligren continue Coyle’s legacy.(8) In 1996, friends and family dedicated a bust of Coyle in the City Hall rotunda to honor his life’s work.(9)

(1)“Nearly half of the business concerns on Nicollet Avenue from Washington Avenue to High Street are saloons, which, because of their location, cater almost exclusively to the floating population [of indigent laborers].” The Minneapolis Journal, March 28, 1908

(2)“71 Jailed in 4 night raids by Sheriffs,” The Sunday Journal, April 18, 1915.

(3)Rosheim, David L. The Other Minneapolis, or The Rise and Fall of the Old Gateway, Minneapolis' Skid Row. Minneapolis: Andromeda Press, 1978.

(4)“Police Close Adonis, Flick Again, Take Films, Lenses,” The Minneapolis Tribune: June 8, 1976.

(5)"F.R.E.E. Records" Box 1 of the Queer Student Cultural Center Collection, part of the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection.

(6) Minnesota Historical Society. "Brian Coyle Papers." Finding Aid: St. Paul, Minnesota History Center Library. http://www.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00020.xml

(7)Brian Coyle Dies. Equal Time.

(8)www.garyschiff.com/, www.voterobert.com/

(9)"Week in Preview" The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, 10/13/1996.

Part of Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: 100 Queer Places in Minnesota History, (1860-1969), (1969-2010)