Reading Material

The present entry is the first in a series of entries on Leo Adams: A Gay Life in Letters, 1928–1952

"[Lady Chatterley's Lover] is, to say the least, a powerful aphrodisiac and I have it on the personal testimony of one who lisps that its descriptions of the normal sex act could do more than the arts of psychoanalysis to make an erring homo renounce his red tie and begin annoying women."––Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, October 12, 1929.[1]

In the early-to-mid twentieth century, before the existence of an active gay press or bookstores, gay men and lesbians necessarily relied on word of mouth and the sharing of books and periodicals among circles of friends for gay-themed reading material.

Leo Adams's letters are a rich source of information about what he and his friends were reading from the late 1920s to the years immediately following World War II––a period that witnessed significant changes in both the quantity and the style of popular gay and lesbian literature.

Adams's most remarkable correspondent in this regard is Merle Macbain, editor of The Greater Chicago Magazine in the late 1920s, and later a Commander in the United States Navy, who served as a technical adviser in the 1955 film Mister Roberts. Perhaps most remarkable about their literary relationship is that Macbain, a straight, married man who boasts of having slept "with at least 300 women," takes such an active interest in Leo Adams's gay reading list.[2]

In many ways, Macbain was a more progressive––more queer, even––reader than Adams, whose taste in imaginative literature ran towards The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post. As the passage quoted at the top of this page suggests [re lisps, red ties, and the term "homo"], Macbain was familiar with the language and codes of the emerging queer subculture of the late 1920s. The Oxford English Dictionary records the earliest use in print of 'homo' in this sense in Max Lief's 1929 novel Hangover (New York: Horace Liveright, 1929). Macbain's usage seems to be quite avant guarde. The red necktie had, by the 1920s, become a recognized signifier of homosexual identity, also suggesting that the border between gay subculture and mainstream popular culture was porous.[3]

Adams did read Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness and recommended it to Macbain. That letter is not among Adams's papers, but Macbain's reply, with his tongue-in-cheek critical commentary, is:

- My dear Leo:

- Yes – I have read “Well of Loneliness” and I am willing to testify that if Miss Radcliffe [sic] Hall can love like she can write she is certainly not sex starved. From beginning to end the book is a rhythmic pleasure, and approaching it as I did from a wholesomely normal and purely impersonal viewpoint I probably appreciated it even more than you did. Yours as ever / Merely Merle[4]

Macbain was not alone among straight readers who enjoyed Hall's ground-breaking lesbian novel. The Well of Loneliness incited an obscenity trial in the United Kingdom and was subsequently banned in Britain. The publisher of the first American edition (New York: Covici Friede, 1928) successfully fought an obscenity charge and the book sold over 100,000 copies in the U.S. in its first year.

Adams and Macbain also shared a taste for a certain kind of "sophisticated sentimentality" in poetry and shared their findings through their correspondence. In the following passage, Macbain responds to a selection forwarded by Adams early in 1932, including a clipping from a back issue of The New Yorker:

- Dear Leo:

- Your poetry, in the selection of which you show a sure instinct for the exact type of sophisticated sentimentality that I permit myself to approve of, is well received. The one with the "vermillion moon" and lips "as white as suicide" is of the stuff that poetry is made of though the author Charles Henri Ford is unknown to me. There seems now to be a small group of nascent versifiers preparing to take the place of the "New Voices" which somehow never fulfilled their promise.[5]

The poem Macbain refers to is Charles Henri Ford's "Interlude." It is not surprising that Adams, as an avid New Yorker reader, would have stumbled upon Ford's poem. What is remarkable (although probably more so as a happy accident than as a bit of conscious foresight) is that Adams should single out the first published piece by the man who would go on to co-author, with Parker Tyler, The Young and Evil, a modernist roman-a-clef about their lives amidst the gay subculture of Greenwich Village in New York City in the early 1930s.[6]

Later in the same letter Macbain demonstrates his familiarity (and his assumption of Adams's familiarity) with two texts that would, even more so than America's own Walt Whitman, cast their influence on the development of gay American fiction and the gay literary imagination in the early twentieth century:

- At present I am reading Huysmans' "Against the Grain". I presume you have read it but if not you should. It was written for you. Dorian Grey [sic] is an inadequate imitation of this ultra-sophisticated story which was written first. [7]

Several editions of an anonymous English translation of J. K. Huysman's 1884 novel A rebour (Against the Grain), with an introduction by the sexologist Havelock Ellis (who also wrote the "appreciation" in Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness) were available in the U.S. by the early 1930s, including a 1930 Modern Library edition. Oscar Wilde himself suggested the connection between The Picture of Dorian Gray and A rebour in a letter to an unidentified correspondent dated April 1892:

- The book in Dorian Gray is one of many books I have never written, but it is partly suggested by Huysmans's A Rebours...It is a fantastic variation on Huysmans's over-realistic study of the artistic temperament in our inartistic age.[8]

In the OutHistory exhibit page titled Wilde, Whitman, and the Gay Literary Style I discuss further the trans-Atlantic influences of Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman on gay literary culture and demonstrate some of that influence in Leo Adams's letters. Here, it is important to note that, after his 1895 conviction for "gross indecency," Wilde's name became almost synonymous with homosexuality. Alan Sinfield has gone so far as to argue that the "dominant twentieth-century queer identity" is constructed "mainly out of elements that came together at the Wilde trials: effeminacy, leisure, idleness, immorality, luxury , insouciance, decadence and aestheticism."[9]

Walt Whitman's induction into the gay canon, on the other hand, came in fits and starts. While he was being hailed in England and Western Europe as the great poet of the manly love of comrades, the American author Harrison Reeves remarked in 1913 "It is rather odd that homosexuals, at least in America, do not regard Whitman as one of themselves or brag about him."[10]

As late as 1932 the question of Whitman's sexuality was quite open in the U.S., and the subject of correspondence between Adams and Macbain:

- Comrade:

- Drop everything and read "Expression in America" by Ludwig Lewisohn a great and exciting record of American literature illuminated by Freudian psychology. You will be especially interested in the chapter on Whitman with its emphatic statement on a point that interested you years ago.[11]

The "emphatic statement" Macbain refers to is this: "I purpose, then, in regard to Walt Whitman, to sweep away once and for all the miasma that clouds and dims all discussion of him and his work. He was a homosexual of the most pronounced and aggressive type."[12] Forty years after Whitman's death, and nearly a decade before F. O. Matthiessen would situate Whitman at the center of the gay American literary tradition, the first major American critic outs him.

Whether or not Adams got around to reading Against the Grain or Lewisohn's emphatic statement in Expression in America is unclear from his letters. His tastes seemed, especially after moving to New York, to have run toward popular literature and magazines.

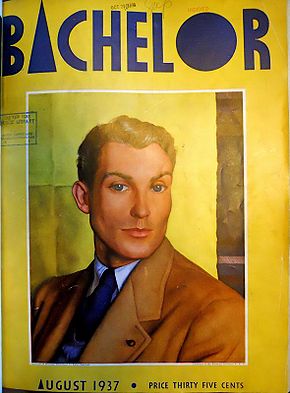

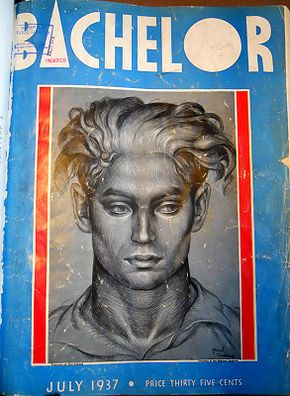

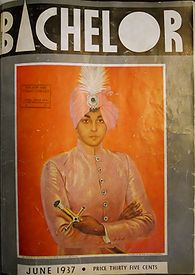

Early in 1937, Adams discovered the magazine that would be seen on the coffee tables of middle-class gay men in bachelor apartments across the city for the coming year. He wrote to his friend Macbain about the find:

- Dear Merle,

- There's a new magazine for men out, named Bachelor. It's swell. I've always maintained that Esquire was just a Jewish edition of Vogue. Well – Bachelor isn't. [13]

The editors of Bachelor, in its inaugural issue, announced that it would be "A visual expression of contemporary thought––mirroring the varied interests of the discerning cosmopolite." The magazine featured covers by artists like Paul Cadmus, Luigi Luccioni, and Charles Baskerville; photos of male celebrities including Cary Grant, Tyrone Power, and a swimsuit-clad Larry Crabbe; and articles by such arbiters of taste as Lucius Beebe.

For gay men who were "aware and out," the designer Neel Bate recalled in a 1982 interview in The Advocate, "Here at last was what looked like 'our' publication, with an editorial staff and contributors who, if not actually gay and out themselves, expressed our interests."[14] As these illustrations suggest, late nineteenth and early twentieth-century modes of dandyism, aestheticism, elitism, athletic masculinity, bachelorhood, and misogyny converged in this early attempt to appeal to an emerging urban gay subculture.

After the war, Adams's letters and those of his friends reflect the increased availability of gay-themed literature by relatively main-stream authors such as Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams, and John Horne Burns. Instead of relying on imported publications and semi-coded references like those in Bachelor, gay men began to have access to quality literature by gay men, about gay men, and they eagerly shared their reading material.

- Dear Leo:

- Have met one very pleasant chap here in town – a new salesman at the Music Shop, who works with radio and television. He's a member of an odd sort of "ménage a trois" – would be fun to break it up, but the healthy influence of Lois is being felt and my urges are well under control.

- Another member of this same ménage, and ex-student here at the Choir College has lent me a book you would be most interested in, I'm sure – "Lucifer with a Book," by John Horne Burns.[15] It's a finely written piece of work, tearing apart a boys school – the sort of thing that has been done before, but I doubt if any author has used such finesse with characterization and so forth. I have been reassured that the school discussed really does exist, and that most of the characters are thinly veiled copies of their proto-types; must be some school! In many respects it reminds me of Princeton, or of what I see of Princeton – many of the same types are evident. Practically the whole student group in the music dept are fruity – most of them very unpleasantly so. But I do recommend the book – and will be eager to hear your reaction!

- I never did find a copy of the book you mentioned to me – "The Pillar and The City," I think – would appreciate you're picking up a copy, if you see one – I shall reimburse you, naturally.[16]

- Dear Bill,

- "Lucifer With a Book" by Burns was published about two years ago, it seems to me. And I think it refers to the Kent school in the foothills of the Berkshires, but I am not positive. It has an awful bitch in it hasn't it? I mean a male one. I have a Pocketbook copy of "The Pillar and The City" awaiting any visit to New York you may make. No charge for the service.

- Do you think that only flairies read Flair?[17]

Adams's correspondence with his friend Bill Giles, a student at Westminster Choir College, also demonstrate the rapidity with which gay men found and read gay-themed reading material and the frequency with which they shared it with each other. The main subject of this exchange, James Barr's Quatrefoil, was, in the assessment of the literary critic Roger Austin, "one of the earliest novels that could have produced a glow of gay pride."[18]

- Dear Leo:

- The books are going to be worn out very shortly, and Quatrefoil[19] especially is a major sensation. I liked it by far the best of the three – The Sling and the Arrow, frankly, bored me stiff. If you think of any other titles I ought to read, please pass them on –– you know how I enjoy broadening (?) my mind.[20]

- Dear Bill,

- I have your note on the educational influence you are wielding at school with my books. Don't let Quatrefoil disappear as I want it back. Have you looked up the dictionary definition of the word? A four leaved flower. Could it be pansy?[21]

Next: Nightlife and Entertainment

Notes

- ↑ Leo Adams Papers, New York Public Library.

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, January 1932. Leo Adams Papers, New York Public Library (hereafter cited by name and date only).

- ↑ See, among others, George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 522; and Shaun Cole, "Macho Man: Clones and the Development of a Masculine Stereotype," Fashion Theory 4 (2000), 126

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, February 18, 1929

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, February 1932 (undated).

- ↑ Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, The Young and Evil (Paris: Obelisk Press, 1933).

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, February 1932

- ↑ Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis, Eds. The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (New York: Henry Holt, 2000), 524.

- ↑ Alan Sinfield, The Wilde Century: Effeminacy, Oscar Wilde and the Queer Moment (London: Cassell, 1994), 11-12.

- ↑ Quoted in Hendrik Marinus Ruitenbeek, Homosexuality and Creative Genius (New York: Astor-Honor, 1967), 126.

- ↑ Merle Macbain to Leo Adams, December 2, 1932.

- ↑ Ludwig Lewisohn, Expression in America (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1932), 199. Emphasis mine.

- ↑ Leo Adams to Merle Macbain, April 19, 1937

- ↑ Quoted in William Norwich, "Fine Print: Broadway Brummells," New York Times, 18 March 2001.

- ↑ John Horne Burns, Lucifer With a Book, (New York: Harper, 1949). Gore Vidal recalled that, in Burns's opinion, "to be a good writer, one must be homosexual, perhaps because his or her marginalized status provides the gay or lesbian author with an objectivity not attainable within mainstream culture." (Gore Vidal, "John Horne Burns," In Homage to Daniel Shays, Collected Essays 1952-1972. [New York: Random House, 1972], 181-185.)

- ↑ William Giles to Leo Adams, September 26, 1950.

- ↑ Leo Adams to William Giles, September 28, 1950.

- ↑ Roger Austen, Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1977.

- ↑ James Barr [James Fugaté], Quatrefoil, (New York: Greenberg, 1959).

- ↑ William Giles to Leo Adams, February 11, 1951.

- ↑ Leo Adams to William Giles, February 14, 1951.