Difference between revisions of "AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989"

| (18 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== '''AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989''' == | == '''AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989''' == | ||

| − | The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities, was transformed by the AIDS crisis. Though AIDS first came to national attention in 1981, in Atlanta, thanks in part to the presence of the Centers for Disease Control, gay activists began organizing around the issue as early as 1983. AID Atlanta, an all-volunteer educational and service organization, was among the first groups that formed. By the end of the decade, there existed a network of HIV/AIDS support and | + | The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities, was transformed by the AIDS crisis. Though AIDS first came to national attention in 1981, in Atlanta, thanks in part to the presence of the Centers for Disease Control, gay activists began organizing around the issue as early as 1983. AID Atlanta, an all-volunteer educational and service organization, was among the first groups that formed. By the end of the decade, there existed a network of HIV/AIDS support and activist groups, including a local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and programs and organizations for women and communities of color. |

| + | |||

| + | Much, though not all, activism during this decade centered on AIDS, and lesbians played an important role in the movement to educate people and to combat the increasingly vocal antigay forces from the Christian right and the Republican Party. As the crisis escalated, Evangelical ministers, among them Charles Stanley of the First Baptist Church of Atlanta, preached that HIV/AIDS was God's punishment for homosexuality. When Georgia native J. B. Stoner, a lifelong segregationist and white supremacist, led a mob confronting civil rights marchers in Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1987, he passed out leaflets that read "Praise God for AIDS" across the top. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the same period, another event of national import occurred, when in 1982, Atlantan Michael Hardwick was arrested in his bedroom for engaging in oral sex with another man. Hardwick appealed, aided by the ACLU and Georgians Opposed to Archaic Laws, but in 1986 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld Georgia’s sodomy statute. In response to the Hardwick case, a strong belief that the U.S. government was failing to adequately address the AIDS crisis, and ongoing discrimination, LGBT Atlantans responded vocally and visibly in local marches and rallies, as well as the second national March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

| − | Image:Atalanta note about Bill Smith.jpg|Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:Atalanta note about Bill Smith.jpg|Newsletter cover, ''Atalanta'', 1980. Seen on the cover is a handwritten note from ''Atalanta'' contributor Margo to Diane, a friend of local activist Bill Smith. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:Atalanta article about Bill Smith.jpg|Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:Atalanta article about Bill Smith.jpg|"In Memoriam Bill Smith," ''Atalanta'', 1980. In her memoriam about Bill Smith, Margo wryly wrote, "He might have been Atlanta's 'Harvey Milk' except that Atlanta is not S.F." Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:Atlanta Gay Center_Ponce_AHC.jpg|Photograph, Atlanta Gay Center, circa 1980. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:Atlanta Gay Center_Ponce_AHC.jpg|Photograph, Atlanta Gay Center, circa 1980. In 1980, the Atlanta Gay Center moved from its original location on West Peachtree Street to Ponce de Leon Avenue. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:First Tuesday candidates rating_1980_AHC.jpg|Flyer, First Tuesday, 1980. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:First Tuesday candidates rating_1980_AHC.jpg|Flyer, First Tuesday, 1980. First Tuesday assessed Republican Newt Gringrich, and many other elected officials, to be "unacceptable" for supporting the anti-gay McDonald amendment, named after local Congressman Larry McDonald, to the Legal Services Corporation Act. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:AID Atlanta newsletter 1983_AHC.jpg|Newsletter, AID Atlanta, 1983. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:AID Atlanta newsletter 1983_AHC.jpg|Newsletter, AID Atlanta, 1983. Pictured here, the first issue of the newsletter predicted that AIDS "has the potential of historically uniting us [LGBT individuals] in a way we have never been united." Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:Pulse_cover.jpg|First issue, ''PULSE'', 1984. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:Pulse_cover.jpg|First issue, ''PULSE'', 1984. Premiering in 1984, ''PULSE'' was one of several short-lived publications in the 1980s. Others included ''Gaybriel'' and ''Gazette''. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:The Journal_Aid Atlanta_1988_AARL.jpg|Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | + | Image:The Journal_Aid Atlanta_1988_AARL.jpg|Newspaper, AID Atlanta, 1986. In the mid-1980s, SCLC joined local efforts to address the issue of disproportionate percentages of HIV/AIDS cases among African Americans. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | Image:BWMT letter_1988_AARL.jpg|Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | + | Image:BWMT letter_1988_AARL.jpg|Letter, National Task Force on AIDS Prevention of the National Association, Black and White Men Together, 1988. In this letter, project director Reggie Williams corresponds with BWMT chapter member Duncan Teague of Atlanta. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

| − | Image:Evangelical Outreach Ministries_1985_AARL.jpg|Printed materials | + | Image:Evangelical Outreach Ministries_1985_AARL.jpg|Printed materials, Evangelical Outreach Ministries (EOM), 1985. By the mid-1980s, various religious organizations existed, including EOM and local synagogue Bet Havarim, to cater to the city's diverse LGBT communities of faith. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Image:Atlanta | + | Image:Atlanta's Gay Ordinance_1986_AARL.jpg|Printed materials, Atlanta's gay ordinance, 1986. The growing LGBT community responded to efforts to repeal newly-won civil rights protections in Atlanta in 1986. Staunch conservative Nancy Schaefer's Citizens for Public Awareness attempted to rescind the city's ordinance but failed. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:Atlanta Couples Together_1986_AARL.jpg|Printed materials, Atlanta Couples Together, 1986. During the 1980s, various social and civic LGBT organizations formed to meet specific community needs, including Atlanta Couples Together. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:TowerLounge_AHC.jpg|Photograph, Tower Lounge staff, circa 1988. Now closed, one of the longest-surviving lesbians bars in the city was the Tower Lounge. In the 1980s, other bars for gay women included Arney's, Deana's One Mo' Time, Rose, Sportspage, and Toolulah's. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:139.jpg|Photograph, Armorettes, circa 1983. For thirty years, the Armorettes, "Camp Drag Queens of the South," entertained locals and visitors alike while establishing a rich tradition of community service. When the Armory closed in the early 2000s, the Armorette's moved to Burkhart's. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:140.jpg|Advertisement featuring performer RuPaul, Weekends, 1984. Until he left for New York in 1987, RuPaul was involved in Atlanta's arts and nightlife scenes, recording and performing songs and starring in the 1986 Jon Witherspoon cult film, ''Starbooty''. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:Insight newsletter_AHC_1985.jpg|Newsletter, the Montgomery Foundation Gender Dysphoric Association, 1985. "Insight," a local monthly publication of the Montgomery Foundation, sought to educate transexual individuals and professional service providers about the issues affecting trans women and men. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| + | Image:Atlanta Gay Guides_1986-1989_AARL.jpg|Directories, 1986-1989. The Atlanta Business and Professional Guild, founded in 1978, was one of several organizations that published annual directories. Now the guides provide historic snapshots of the city's LGBT infrastructure of organizations, social groups, and businesses during the 1980s. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | |||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

| − | Image:131.jpg|Cover, ''The News'', 1985. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:131.jpg|Cover, ''The News'', 1985. Pictured here, ''The News'', a publication of the Atlanta Gay Center, reported on the ongoing Hardwick Case and the Center's move to Twelfth Street in Midtown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:Atlanta March 1987_AARL.jpg|Printed materials | + | Image:Atlanta March 1987_AARL.jpg|Printed materials, Atlanta committee for the National March on Washington, 1987. During the 1980s, LGBT Atlantans continued community development efforts while also fostering a national gay identity, illustated here by preparations for the 1987 National March on Washington. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | Image: | + | Image:Cover_ETC_1989_AARL.jpg|Cover, ''Etcetera'' 1989. In addition to local and national marches for LGBT civil rights, LGBT Atlantans partipated in other human rights demonstrations, including the Martin Luther King Day Parade. Pictured on the 27 January-2 February cover of ''Etcetera'' are members of the African American Lesbian Gay Alliance marching in the parade. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | Image:Names Project_1988_AARL.jpg|Printed materials | + | Image:Names Project_1988_AARL.jpg|Printed materials, [[AIDS Memorial Quilt: November 1985-present|Names Project]], Atlanta, Georgia, 1988. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

Image:146.jpg|Photograph, James Heverly (left), Layton Gregory (center), and Fritz Rathmann, circa 1983. Heverley, along with Patrick Coleman and Jaye Evans, published the popular ''Etcetera'' magazine. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | Image:146.jpg|Photograph, James Heverly (left), Layton Gregory (center), and Fritz Rathmann, circa 1983. Heverley, along with Patrick Coleman and Jaye Evans, published the popular ''Etcetera'' magazine. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| − | Image:Gays and Lesbians for Maynard_1989.jpg|Printed materials | + | Image:Gays and Lesbians for Maynard_1989.jpg|Printed materials, LGBT support of Maynard Jackson's mayoral campaign, 1989. By the end of the decade, local politicians openly courted LGBT voters and support. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

| − | Image:Atlanta River Expo_1988_AARL.jpg|Photograph, Atlanta River Expo participants, 1988. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | + | Image:Atlanta River Expo_1988_AARL.jpg|Photograph, Atlanta River Expo participants, 1988. By its tenth anniversary in 1988, the Atlanta River Expo had expanded from a daylong rafting festival, started in 1978, to four days of parties and performances that drew crowds of gay men from across the Southeast. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. |

| − | Image:Miss Gay Atlanta Pageant_program_1989.jpg|Program, Miss Gay Atlanta Pageant, 1989. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | + | Image:Miss Gay Atlanta Pageant_program_1989.jpg|Program, Miss Gay Atlanta Pageant, 1989. While the Miss Gay Atlanta pageant began modestly in 1970 at the Rathskellar in Midtown, its popularity continued throughout the 1980s. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

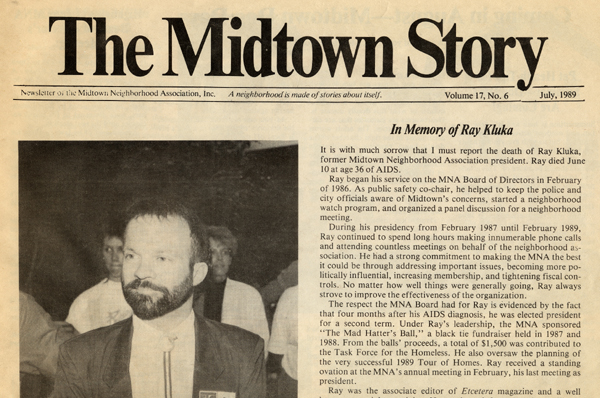

[[Image:TheMidtownStoryV17N6.jpg|thumb|none|635px|Cover, ''The Midtown Story'', 1989. Throughout the 1980s, the city's gay publications chronicled the devastation wrought by the AIDS crisis, including the death of Ray Kluka, a tireless champion of gay rights, in 1989. In 1979, Kluka served as the male co-chair of the Southeast region committee for the national March on Washington. Over the next several years, he held leadership positions with the Atlanta Gay Center, First Tuesday, and Midtown Neighborhood Association and served as an editor for ''Etcetera''. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.]] | [[Image:TheMidtownStoryV17N6.jpg|thumb|none|635px|Cover, ''The Midtown Story'', 1989. Throughout the 1980s, the city's gay publications chronicled the devastation wrought by the AIDS crisis, including the death of Ray Kluka, a tireless champion of gay rights, in 1989. In 1979, Kluka served as the male co-chair of the Southeast region committee for the national March on Washington. Over the next several years, he held leadership positions with the Atlanta Gay Center, First Tuesday, and Midtown Neighborhood Association and served as an editor for ''Etcetera''. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the clip below, local entertainment personalities RuPaul and Wanda Peek document their participation in the 1987 march in Forsyth County. | ||

| + | <youtube>hntVo25hOgo</youtube> | ||

| + | |||

[[Parties and Pride - 1970 to 1979]] | [[Parties and Pride - 1970 to 1979]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:24, 14 June 2010

AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989

The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities, was transformed by the AIDS crisis. Though AIDS first came to national attention in 1981, in Atlanta, thanks in part to the presence of the Centers for Disease Control, gay activists began organizing around the issue as early as 1983. AID Atlanta, an all-volunteer educational and service organization, was among the first groups that formed. By the end of the decade, there existed a network of HIV/AIDS support and activist groups, including a local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and programs and organizations for women and communities of color.

Much, though not all, activism during this decade centered on AIDS, and lesbians played an important role in the movement to educate people and to combat the increasingly vocal antigay forces from the Christian right and the Republican Party. As the crisis escalated, Evangelical ministers, among them Charles Stanley of the First Baptist Church of Atlanta, preached that HIV/AIDS was God's punishment for homosexuality. When Georgia native J. B. Stoner, a lifelong segregationist and white supremacist, led a mob confronting civil rights marchers in Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1987, he passed out leaflets that read "Praise God for AIDS" across the top.

During the same period, another event of national import occurred, when in 1982, Atlantan Michael Hardwick was arrested in his bedroom for engaging in oral sex with another man. Hardwick appealed, aided by the ACLU and Georgians Opposed to Archaic Laws, but in 1986 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld Georgia’s sodomy statute. In response to the Hardwick case, a strong belief that the U.S. government was failing to adequately address the AIDS crisis, and ongoing discrimination, LGBT Atlantans responded vocally and visibly in local marches and rallies, as well as the second national March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987.

Flyer, First Tuesday, 1980. First Tuesday assessed Republican Newt Gringrich, and many other elected officials, to be "unacceptable" for supporting the anti-gay McDonald amendment, named after local Congressman Larry McDonald, to the Legal Services Corporation Act. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Letter, National Task Force on AIDS Prevention of the National Association, Black and White Men Together, 1988. In this letter, project director Reggie Williams corresponds with BWMT chapter member Duncan Teague of Atlanta. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Printed materials, Evangelical Outreach Ministries (EOM), 1985. By the mid-1980s, various religious organizations existed, including EOM and local synagogue Bet Havarim, to cater to the city's diverse LGBT communities of faith. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Printed materials, Atlanta's gay ordinance, 1986. The growing LGBT community responded to efforts to repeal newly-won civil rights protections in Atlanta in 1986. Staunch conservative Nancy Schaefer's Citizens for Public Awareness attempted to rescind the city's ordinance but failed. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Photograph, Tower Lounge staff, circa 1988. Now closed, one of the longest-surviving lesbians bars in the city was the Tower Lounge. In the 1980s, other bars for gay women included Arney's, Deana's One Mo' Time, Rose, Sportspage, and Toolulah's. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, Armorettes, circa 1983. For thirty years, the Armorettes, "Camp Drag Queens of the South," entertained locals and visitors alike while establishing a rich tradition of community service. When the Armory closed in the early 2000s, the Armorette's moved to Burkhart's. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Advertisement featuring performer RuPaul, Weekends, 1984. Until he left for New York in 1987, RuPaul was involved in Atlanta's arts and nightlife scenes, recording and performing songs and starring in the 1986 Jon Witherspoon cult film, Starbooty. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Newsletter, the Montgomery Foundation Gender Dysphoric Association, 1985. "Insight," a local monthly publication of the Montgomery Foundation, sought to educate transexual individuals and professional service providers about the issues affecting trans women and men. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Directories, 1986-1989. The Atlanta Business and Professional Guild, founded in 1978, was one of several organizations that published annual directories. Now the guides provide historic snapshots of the city's LGBT infrastructure of organizations, social groups, and businesses during the 1980s. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Printed materials, Atlanta committee for the National March on Washington, 1987. During the 1980s, LGBT Atlantans continued community development efforts while also fostering a national gay identity, illustated here by preparations for the 1987 National March on Washington. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Cover, Etcetera 1989. In addition to local and national marches for LGBT civil rights, LGBT Atlantans partipated in other human rights demonstrations, including the Martin Luther King Day Parade. Pictured on the 27 January-2 February cover of Etcetera are members of the African American Lesbian Gay Alliance marching in the parade. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Printed materials, Names Project, Atlanta, Georgia, 1988. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Photograph, Atlanta River Expo participants, 1988. By its tenth anniversary in 1988, the Atlanta River Expo had expanded from a daylong rafting festival, started in 1978, to four days of parties and performances that drew crowds of gay men from across the Southeast. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

In the clip below, local entertainment personalities RuPaul and Wanda Peek document their participation in the 1987 march in Forsyth County. <youtube>hntVo25hOgo</youtube>

Parties and Pride - 1970 to 1979

Collective Power and Culture Wars - 1990 to 1999

Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History <comments />