Collective Power and Culture Wars - 1990 to 1999

Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History

Collective Power and Culture Wars - 1990 to 1999

Atlanta continued to be a magnet in the Southeast in the 1990s, adding newcomers, including gay women and men, to its ranks at a rapid clip. As they had in the past, LGBT individuals moved to the city for educational and economic opportunities but also for its vital infrastructure of gay social, political, and religious organizations, businesses, and gathering places. For supporters of gay rights, the notion of a unified “gay community” was a powerful concept that galvanized and mobilized people into action. It was a strategy equally attractive to antigay forces, however, which on the grounds of “family values” sought to limit gay rights and visibility. In truth, Atlanta’s “community” continued to fracture along lines of gender, race, and class. As a national gay rights movement grew stronger during the decade, gay and lesbian Atlantans, as in other areas, discovered a new sense of collective power.

In their daily lives during the 1990s, more gay and lesbian Atlantans began holding positions of power, often without trying to conceal their sexual identities. This decade saw the growth of business and professional networking groups; gay and lesbian elected officials; entrepreneurship; and local and national celebrities. In Atlanta, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals proved adept at working together to challenge discrimination they experienced at home, at school, at work, and from their elected representatives. They continued celebrating and commemerating in Pride marches and began collecting, preserving, and exhibiting their collective past. They formed strategic alliances with LGBT groups within the area and in neighboring cities and states, as well as with straight allies—families, friends, co-workers, and elected officials. And for the first time, they were operating from a position of power.

By the end of the twentieth century, the population of the Atlanta metropolitan area had grown to over four million. The area also had one of the nation’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Many of the trends and forces that had shaped the city throughout the century—urban development and suburban expansion, race relations, business and transportation—continued to affect the way Atlantans lived and the landscape of the city and its environs. In the 1990s Atlanta outpaced all other comparable metropolitan areas in terms of growth. The city’s biracial composition changed as new ethnic groups immigrated from Asian, African, and Central and South American countries. The lives of Atlanta’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender citizens reflected these changes, as they continued to find spaces of their own.

Photograph, George Woodard (left), Freddie Styles (center), and Lonnie Broughton, circa 1993. Freddie Styles embarked on his first cruise with Woodard and Broughton, both of whom died in the 1990s, ending more than 20 years of friendship. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, Karl Allquist, circa 1990. After developing Kaposi's sarcoma in 1990, Allquist divulged his HIV status to partner William Penn, who discovered after Allquist's death in 1992 the journal in which he chronicled his ordeal. Photographer William Penn. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Printed materials, Cheryl Summerville and Cracker Barrel, 1990s. When the Cracker Barrel Restaurant in Lithonia, Georgia, fired Cheryl Summerville for being a lesbian, it led to protests that quickly drew national media attention. Summerville's story is one of several featured in the 1996 documentary Out at Work, which examines antigay discrimination in the workplace. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

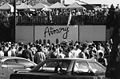

Photograph, Atlanta participants, Washington D.C., 1993. Atlantans were among the one million women and men who marched for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual rights in 1993. While the tone was more hopeful than the 1987 March, the 1993 agenda included the onging battle against AIDS, "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," and much more. Photographer Alli Royce Soble. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, Andrew Parker (left) and Erika Linstrom, Washington, D.C., 1993. For younger generations of lesbian and gay Atlantans, including Parker and Linstrom, it was their first opportunity to be part of history in the making. Photographer Wesley Chenault. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, from left to right are Lynne Peterson, John Meeks, Renee Palmer, and Jeri Sassany, Washington, D.C., 1993. Palmer attended her first Pride march in the early 1990s. There she met members of the local chapter of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PGLAG), in particular Jeri and John Sassany. Over the years, the Sassanys' social circle came to include numerous "adopted" women and men, including Palmer, John Meeks and his partner, John Townsend. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, ADODI Muse members Duncan E. Teague (left), Tony Daniels (center), and Malik M. L. Williams, circa 1996. ADODI Muse, Atlanta's only African American gay performance poets collective, was created in 1995. After Daniels died in an automobile accident in 1998, Anthony Antoine, a musician and producer, later joined the ensemble. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Brochure, ZAMI, circa 1995. In 1990, a group of lesbian members of the African American Lesbian Gay Alliance (AALGA) left and formed ZAMI, a name which honors the late poet Audre Lorde. In the late 1990s, the organization began awarding Audre Lorde Scholarships to black lesbians and gay men. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Photograph, Pat Hussain, 1996. After the Cobb County Commission passed an antigay resolution in 1993, Pat Hussain and Jon-Ivan Weaver established Olympics Out of Cobb (OOC) to pressure the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games to move events and sports venues from the county. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, Jon-Ivan Weaver, 1996. After several protests and attention from national media, women's volleyball was relocated from the Cobb Galleria Centre to the Coliseum at the University of Georgia in Athens. Hussain and Weaver chronicled their experiences in Olympics Out of Cobb Spiked!, published in 1996. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Cover, Venus magazine, 1995. Publisher Charlene Cothran named and dedicated the first issue of the magazine for lesbians and gay men of color to Venus Landin, a respected community leader and activist who died in 1993. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Flyer, community forum at First Existentialist Church, 1993. In response to local and national attacks by conservative and fundmentalist groups and legislators, LGBT Atlantans organized to maintain the social and political gains made in the 1980s and 1990s. "Not Georgia Next!," sponsored by AALGA, the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, and the First Existentialist Congregation, serves as one example. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Photograph, Mo B. Dick, My Sisters' Room, 1998. Bars for men outnumbered those for women thoughout the 1980s and 1990s. Those that existed for lesbians, including the popular My Sisters' Room, provided a valuable space for socializing and hosting fund-raisers and private celebrations. Photographer Alli Royce Soble. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, Oracle Corporation Christmas Party, circa 1998. In the mid-1990s, Oracle Corporation, headquartered in Redwood Shores, California, began offering benefits to the domestic partners of its employees, including those the Atlanta office. In 1996, John Oxedine started a campaign against domestic partner benefits when he prohibited insurance companies based in Georgia from offering them to clients. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Cover, Venus, Fall 1995. In this special "Black Gay Pride" issue, editor Charlene Cothran reported that an outstanding celebration was being planned, though no official committee was organizing it. A year later, a small group of African American gay women and men created the non-profit In The Life Atlanta to plan programs and social offerings for the popular event held during the Labor Day weekend. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Invitation, AARL, 1997. Individual efforts to increase awareness about LGBT history in Atlanta date to the 1980s and include works created by Elizabeth Knowlton and Cal Gough. In the 1990s, public institutions began acquiring collections from and creating programming about Atlanta's LGBT community, illustated by the invitation pictured here. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Printed materials, Atlanta Gender Explorations (AGE), 1990s. AGE was an outgrowth of the American Educational Gender Information Service, a nonprofit clearinghouse for information about transgender and transsexual issues founded by Dallas Denny in September 1990. According to an AGE brochure, the support group provided "a safe, caring, atmosphere in which crossdressers, transgenderists, transsexual persons" could "discuss and explore their gender issues." Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Printed materials, Southern Comfort Conference, 1995. In 1990, the Southern Comfort Conference was organized to provide support and resources for transgender individuals in the region. A little more than a decade later, Southern Comfort, a documentary, brought great exposure to the organization and the subject of transexuals. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

Photograph, Kristal Manning (left) and Melinda McBride, 1999. In Atlanta, as in other cities across the country, LGBT women and men increasingly celebrated their relationships in public ceremonies in the 1990s. Some women and men, including Manning and McBride, also began families. Photographer Alli Royce Soble. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Brochure, Fourth Tuesday, 1997. In the 1990s, several lesbian organizations served the community through scholarships, educational programs, social events, and networking opportunities. ZAMI catered to African American women, while Fourth Tuesday, organized in the early 1980s, served a mostly white constituency. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph, Cathy Woolard (right) and Bill Clinton, Washington, D.C., 1999. The late 1990s witnessed several firsts for gay politicians in Atlanta, including Cathy Woolard, who became the city's first openly gay elected official in 1997. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.

Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History

AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989

National Agendas and Local Actions - 2000 to 2009

<comments />