|

|

| (27 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | ==Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House== | | ==Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House== |

| | | | |

| − | Adapted without source citations from Jonathan Ned Katz's book ''Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality.'' | + | Adapted from Jonathan Ned Katz's book ''Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality'' (University of Chicago Press, 2001). The source citations are available in the printed edition. |

| | | | |

| | | | |

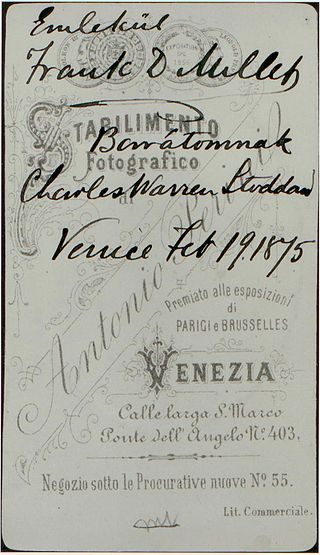

| − | By 1874, the American travel journalist Charles Warren Stoddard had | + | '''Photo (right): Charles Warren Stoddard''' |

| − | given up on the South Seas, the site of earlier sensual adventures recorded coyly coded form in published articles. He was now pursuing his erotic destiny in Italy.<ref>Ada[ted and republished on OutHistory without the original backnote citations from Jonathan Ned Katz's "Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House", Chapter 14, in ''Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pages 202-219.</ref> | + | |

| | + | [[File:AaaStoddard, C.W. photo.jpeg|320px|right]] |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | By November 1874, the American travel journalist Charles Warren Stoddard had given up on the South Seas, the site of earlier sensual adventures recorded in coyly coded form in published articles. He was now pursuing his erotic destiny in Italy.<ref>Adapted and republished on OutHistory without the original backnote citations from Jonathan Ned Katz's "Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House", Chapter 14, in ''Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pages 202-219.</ref> |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| Line 13: |

Line 17: |

| | "We looked at each other and were acquainted in a minute. Some | | "We looked at each other and were acquainted in a minute. Some |

| | people understand one anotherer at sight, and don't have to try, either." | | people understand one anotherer at sight, and don't have to try, either." |

| − | Stoddard's recollection of this meeting was published in Boston's National Magazine | + | Stoddard's recollection of this meeting was published in Boston's ''National Magazine'' |

| | in 1906. | | in 1906. |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Stoddard's new friend was the American artist Francis Davis Millet. | + | Stoddard's friend was the American artist Francis Davis Millet.<ref>Stoddard and Millet had met earlier in Rome, according to {{Engstrom}}, page 62.</ref> |

| − | The two had heard of each other, but never met. Stoddard was thirty-one

| + | Stoddard was thirty-one in 1874, and Millet was twenty-eight. |

| − | in 1874, and Millet was twenty-eight. | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| Line 25: |

Line 28: |

| | a Massachusetts doctor, had served as a Union army surgeon, and in | | a Massachusetts doctor, had served as a Union army surgeon, and in |

| | 1864, the eighteen-year-old Frank Millet had enlisted as a private, serving | | 1864, the eighteen-year-old Frank Millet had enlisted as a private, serving |

| − | first as a drummer boy and then as a surgeon's assistant. Young Millet | + | first as a drummer boy and then as a surgeon's assistant. |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | Young Millet |

| | graduated from Harvard in 1869, with a master's degree in modern | | graduated from Harvard in 1869, with a master's degree in modern |

| − | languages and literature. While working as a journalist on Boston newspapers, | + | languages and literature. While working as a journalist on Boston newspapers, |

| | he learned lithography and earned money enough to enroll in | | he learned lithography and earned money enough to enroll in |

| | 1871 in the Royal Academy, Antwerp. There, unlike anyone before him, | | 1871 in the Royal Academy, Antwerp. There, unlike anyone before him, |

| | he won all the art prizes the school offered and was officially hailed by the | | he won all the art prizes the school offered and was officially hailed by the |

| − | king of Belgium. As secretary of the Massachusetts commission to the Vienna | + | king of Belgium. |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | As secretary of the Massachusetts commission to the Vienna |

| | exposition in 1873, Millet formed a friendship with the American | | exposition in 1873, Millet formed a friendship with the American |

| − | Charles Francis Adams, and then traveled through Turkey, Romania, | + | Charles Francis Adams, Junior, and then traveled through Turkey, Romania, |

| | Greece, Hungary, and Italy, finally settling in Venice to paint. | | Greece, Hungary, and Italy, finally settling in Venice to paint. |

| | | | |

| | | | |

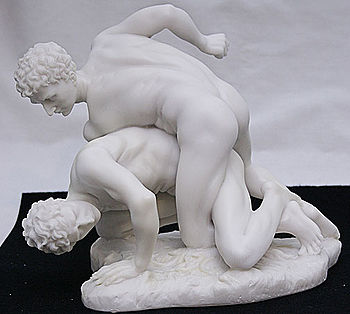

| − | At the opera, as Stoddard recalled, Millet immediately asked, "Where | + | '''Photo (below): Francis Davis Millet. Back of photo (below): dedicated to Stoddard, February 19, 1875. In Hungarian "Emlekül" means "In memory of" and "Barátomnak" means "For my friend".'''<ref>Photos: Syracuse University Library. Thanks to James Steakley for suggesting that the inscription is in Hungarian.</ref> |

| − | are you going to spend the Winter?" He then invited Stoddard to live in

| + | |

| − | his eight-room rented house. "Why not come and take one of those | + | [[File:AaaMillet,F.D.photo.jpeg|320px|right]][[File:AaaMillet,back of photo.jpeg|320px|right]] |

| − | rooms?" the painter offered, "I'll look after the domestic affairs" -- is this | + | |

| − | a Stoddard double entendre? | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | At the opera, as Stoddard recalled, Millet immediately asked, "Whereare you going to spend the Winter?" He then invited Stoddard to live in his eight-room rented house at 262 Calle de San Dominico, the last residence on the north side of San Marco, next to a shipyard and the Public Garden.<ref>The address is given by {{Engstrom}}, page 60. A Google Maps view of the area is available at: http://maps.google.com/maps?ftr=earth.promo&hl=en&utm_campaign=en&utm_medium=van&utm_source=en-van-na-us-gns-erth&utm_term=evl</ref> "Why not come and take one of those rooms?" the painter offered, "I'll look after the domestic affairs" -- is this a Stoddard double entendre? |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| Line 51: |

Line 97: |

| | The two lived together during the winter of 1874-75, though Stoddard | | The two lived together during the winter of 1874-75, though Stoddard |

| | did not take one of the extra rooms. Millet's romantic letters to Stoddard | | did not take one of the extra rooms. Millet's romantic letters to Stoddard |

| − | indicate that the men shared a bed in an attic room overlooking the

| + | make it clear that the men shared a bed in an attic room overlooking the |

| | Lagoon, Grand Canal, and Public Garden. | | Lagoon, Grand Canal, and Public Garden. |

| | | | |

| Line 57: |

Line 103: |

| | Lack of space did not explain | | Lack of space did not explain |

| | this bed sharing, and Stoddard's earlier and later sexual liaisons with men, | | this bed sharing, and Stoddard's earlier and later sexual liaisons with men, |

| − | his written essays and memoirs, and Millet's letters to Stoddard, all | + | his written essays and memoirs, and Millet's letters to Stoddard, provide good evidence that their intimacy found active affectionate and erotic expressIon. |

| − | strongly suggest that their intimacy found active affectionate and erotic

| |

| − | expressIon. | |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| Line 67: |

Line 111: |

| | Stoddard's exclusive interest in men the less usual. In any case, the ranging | | Stoddard's exclusive interest in men the less usual. In any case, the ranging |

| | of Millet's erotic interest between men and women was not then understood | | of Millet's erotic interest between men and women was not then understood |

| − | as "bisexual", a mix of "homo" and "hetero." The hetero-homo division has not yet been invented. | + | as "bisexual", a mix of "homo" and "hetero." The hetero-homo division had not yet been invented. |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| Line 100: |

Line 144: |

| | early in his relationship with Millet, the journalist wrote of "spoons" with | | early in his relationship with Millet, the journalist wrote of "spoons" with |

| | "my fair" (an unnamed woman) in a gondola's covered "lovers' cabin," and | | "my fair" (an unnamed woman) in a gondola's covered "lovers' cabin," and |

| − | of "her memory of a certain memorable sunset-but that is between us | + | of "her memory of a certain memorable sunset--but that is between us |

| | two!" Stoddard here changed the sex of his fair one when discussing | | two!" Stoddard here changed the sex of his fair one when discussing |

| − | "spooning" (kissing) in his published writing. Walt Whitman also employed the literary subterfuge, changing the sex of the male who inspired a poem to a female in the final, published version. | + | "spooning" (kissing, making out) in his published writing. Walt Whitman also employed this literary subterfuge, changing the sex of the male who inspired a poem to a female in the final, published version. |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==Touring Italy: February 1875== | + | ==Touring Italy: January 1875== |

| − | In February 1875, Stoddard, seeking new cities to write about for the | + | In late January 1875, Stoddard, seeking new cities to write about for the |

| | ''Chronicle'', made a three-week tour of northern Italy, revising these memoirs | | ''Chronicle'', made a three-week tour of northern Italy, revising these memoirs |

| − | twelve years later for the Catholic magazine Ave Maria, published at | + | twelve years later for the Catholic magazine ''Ave Maria'', published at |

| | Notre Dame University. Stoddard wrote that his unnamed painter friend | | Notre Dame University. Stoddard wrote that his unnamed painter friend |

| | accompanied him as guide and "companion-in-arms," a punning name | | accompanied him as guide and "companion-in-arms," a punning name |

| Line 129: |

Line 173: |

| | was "hoisted into our compartment." But "no sooner did the train move | | was "hoisted into our compartment." But "no sooner did the train move |

| | off, than he was overcome, and, giving way to his emotion, he lifted up | | off, than he was overcome, and, giving way to his emotion, he lifted up |

| − | his voice like a trumpeter;' filling the car with "lamentations." For half an | + | his voice like a trumpeter," filling the car with "lamentations." For half an |

| | hour "he bellowed lustily, but no one seemed in the least disconcerted at | | hour "he bellowed lustily, but no one seemed in the least disconcerted at |

| | this monstrous show of feeling; doubtless each in his turn had been similarly affected." | | this monstrous show of feeling; doubtless each in his turn had been similarly affected." |

| Line 151: |

Line 195: |

| | | | |

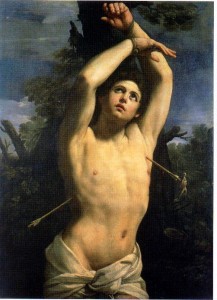

| | Among the statues that Stoddard admired in Florence were "The | | Among the statues that Stoddard admired in Florence were "The |

| − | Wrestlers, tied up in a double-bow of monstrous muscles"- another culturally | + | Wrestlers, tied up in a double-bow of monstrous muscles" -- another culturally |

| | sanctioned icon of physical contact between, in this case, scantily | | sanctioned icon of physical contact between, in this case, scantily |

| | clad men. | | clad men. |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | In Genoa, Stoddard recalled seeing a "captivating" painting of the

| + | '''Right: "The Wrestlers". Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.''' |

| − | "lovely martyr" St. Sebastian, a "nude torso" of "a youth as beautiful as

| + | [[File:Jnk--Pankratiasts(Wrestlers).jpeg|right|350px]] |

| − | Narcissus"--yet another classic, undressed male image suffused with

| |

| − | eros. The "sensuous element predominates," in this sculpture, said Stoddard,

| |

| − | and "even the blood-stains cannot disfigure the exquisite lustre of

| |

| − | the flesh." <<ADD PICTURE OF SAINT SEBASTIAN, if possible from Genoa>>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | In Sienna, Stoddard recorded, he and his companion-in-arms slept in

| |

| − | a "great double bed ... so white and plump it looked quite like a gigantic

| |

| − | frosted cake-and we were happy." The last phrase directly echoes

| |

| − | Stoddard's favorite Walt Whitman Calamus poem in which a man's friend lies

| |

| − | "sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night" -- "and that night I was happy.'' Sleeping happily with Millet in that cake/bed, Stoddard

| |

| − | again linked food and bodily pleasure.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==Back in Venice: Spring 1875==

| |

| − | Back in their Venice home in spring 1875, Stoddard recalled one day

| |

| − | seeing "a tall, slender and exceedingly elegant figure approaching languidly."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==A. A. Anderson==

| |

| − | This second American artist, A. A. Anderson, appeared one Sunday

| |

| − | at Millet's wearing a "long black cloak of Byronic mold," one corner

| |

| − | of which was "carelessly thrown back over his arm, displaying a lining of

| |

| − | cardinal satin." The costume was enhanced by a gold-threaded, damask

| |

| − | scarf and a broad-brimmed hat with tassels.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | In Stoddard's published

| |

| − | memoirs, identifying Anderson only as "Monte Cristo," the journalist recalled

| |

| − | the artist's "uncommonly comely face of the oriental--oval and almond-

| |

| − | eyed type.'' Entranced by the "glamor" surrounding Monte

| |

| − | Cristo, Stoddard soon passed whole days "drifting with him" in his gondola,

| |

| − | or walking ashore.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Invited to dinner by Monte Cristo, Stoddard and his friend (Millet)

| |

| − | found Monte occupying the suite of a "royal princess, it was so ample and

| |

| − | so richy furnished.'' (Monte was a "princess,"' Stoddard hints.) Funded

| |

| − | by an inheritance from dad, Monte had earlier bought a steam yacht and

| |

| − | cruised with an equally rich male friend to Egypt, then given the yacht

| |

| − | away to an Arab potentate. Later, while Stoddard was visiting Paris, he

| |

| − | found himself at once in the "embrace of Monte Cristo," recalling: "That

| |

| − | night was Arabian, and no mistake!" Stoddard's reference to The Arabian Nights)

| |

| − | a classic text including man-love scenes, also invoked a western mystique of "oriental" sex.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==To England and Robert William Jones==

| |

| − | After the beautiful Anderson left Venice, Stoddard, the perennial

| |

| − | rover, found it impossible to settle down any longer in the comfortable,

| |

| − | loving domesticity offered by Millet. The journalist may also have needed

| |

| − | new sights to inspire the travel writing that supported him. He therefore

| |

| − | set off for Chester, England, to see Robert William Jones, a fellow with

| |

| − | whom, a year earlier, he had shared a brief encounter and who had since

| |

| − | been sending him passionate letters.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Stoddard's flight, after living with

| |

| − | Millet for about six months, marked a new phase in their relationship.

| |

| − | Millet now became the devoted pursuer, Stoddard the ambivalent pursued.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard, May 10, 1875==

| |

| − | From Venice, Millet wrote affectionately to Stoddard on May 10,

| |

| − | 1875, calling him "Dear Old Chummeke"--explaining, "I call you

| |

| − | chummeke," the "diminutive of chum,"' because "you are already 'chum'

| |

| − | but have never been chummeke before. Flemish you know." "Chum" and

| |

| − | its variations constituted a common, positive name

| |

| − | among nineteenth-century male intimates, one of the terms by which

| |

| − | they affirmed the special character of their tie.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Claiming he had not much to say because he "let out" so much in his

| |

| − | first letter (not extant, significantly and unfortunately) Millet reported

| |

| − | that he had a new pet. He had told their mutual friends, the Adamses, that

| |

| − | he had "named the new dog Charles Warren Stoddard Venus, though "it

| |

| − | wasn't that kind of a dog" (not, that is, a dog of mixed, ambiguous sex). To Stoddard, Millet certainly referred to Stoddard's large admixture of

| |

| − | the feminine and perhaps to Stoddard's sexual intrest in men. To the

| |

| − | Adamses, Millet was probably perceived to refer only to Stoddard's effeminacy.

| |

| − | The dog's name "was not a question of sex,"' Millet had stressed to the

| |

| − | Adamses, "but of appropriateness."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | The dog's-and Stoddard's-ambiguous masculinity had obviously

| |

| − | been the subject of some lighthearted banter between Millet and the

| |

| − | Adamses. But Millet's reference to Stoddard's effeminacy probably did not

| |

| − | then bring erotic infractions to this Adams family's mind, nor is it likely to

| |

| − | have suggested to them the sexual aspect of the relationship between these

| |

| − | men. Gender deviance and erotic nonconformity were not yet linked as

| |

| − | they would be after the installation of homosex and heterosex.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Another dog, Tom, "sleeps in your place now and fills it all up, that is,

| |

| − | the material space he occupies, crowding me out of bed very offen." Stoddard's

| |

| − | body was absent, but his spirit lingered on.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | "Miss you?" Millet asked. He answered: "Bet your life. Put yourself in

| |

| − | my place. It isn't the one who goes away who misses, it is the one who

| |

| − | stays. Empty chair, empty bed, empty house." Millet's desire for Stoddard's

| |

| − | bodily presence is palpable in his words.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | "So, my dear old cuss;' Millet ended warmly, "with lots of love I am

| |

| − | thine -- as you need not be told." He had obviously declared his love many times earlier.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: May 26, 1875==

| |

| − | He was working on a painting that called for two boy models, "posing

| |

| − | two small cusses--the naked ones-together,"' Millet wrote to Stoddard

| |

| − | on May 26 (again, the talk was of nude male flesh). But the hot, dustladen,

| |

| − | dry wind of Venice, lightning flashes, and "the mercurial little

| |

| − | cusses" made him feel that he had "nearly ruined what good there was on

| |

| − | the canvas." Millet wished Stoddard was present to "make me feel that I

| |

| − | have not done so awfully bad work today."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

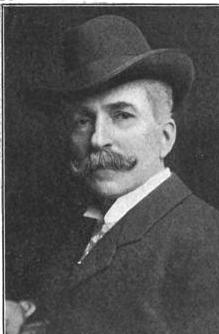

| − | "No gossip to speak of," Millet reported, except that a mutual male | + | In Genoa, Stoddard recalled seeing a "captivating" painting of the |

| − | friend "does no work but spoons with Miss Kelley. "Spoon" appeared repeatedly

| + | "lovely martyr" St. Sebastian, a "nude torso" of "a youth as beautiful as |

| − | in Millet's letters and in Stoddard's published journalism, with

| + | Narcissus"--yet another classic, undressed male image suffused with |

| − | varying degrees of romantic and sexual intimation.

| + | eros. The "sensuous element predominates," in this art work, said Stoddard, |

| | + | and "even the blood-stains cannot disfigure the exquisite lustre of |

| | + | the flesh." |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Spooning reminded Millet that he had had "a squaring up" with Charlotte

| + | '''Right: Guido Reni. "St. Sebastian." Galleria di Palazzo Rosso, Genoa, Italy.''' |

| − | ("Donny") Adams, the eighteen-year-old daughter of their good

| + | [[File:St.Sebastian.jpeg|300px|right]] |

| − | friends. Millet had told Donny "exactly what I thought of her going off with one fellow and coming home with another." In response, she had

| |

| − | tried to "put it all on to me:' saying "I alone was touchy." But Millet had

| |

| − | told her Stoddard agreed with his criticism, "and then she seemed very

| |

| − | anxious to beg my pardon etc. which was not granted."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Millet's high-handed objection to what he considered Donny's breach

| |

| − | of dating etiquette shows him identifying with a man done wrong, supposedly,

| |

| − | by a woman. Criticizing Donny's inconstancy in ditching one

| |

| − | man for another, Millet may have applied to her the same standard to

| |

| − | which he held himself. He was certainly constant in his romantic devotion

| |

| − | to Stoddard, despite the journalist's inconstancy. Stoddard, off with

| |

| − | Monte Cristo and Robert William Jones, clearly applied a less rigid rule

| |

| − | to his own liaisons.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Donny Adams had ended this confrontation by reporting one of her

| |

| − | men friends' suggestions: Millet was gaining weight that winter "because

| |

| − | I liked her and did not care to see another fellow go with her." Donny and

| |

| − | her man friend did not perceive that Millet's romantic-erotic interest was

| |

| − | focused then on Stoddard. Men's erotic romances with men were invisible

| |

| − | because at this time in the public consciousness, there was only one

| |

| − | kind of erotic-romantic attraction-toward the other, different sex.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Millet asked Stoddard to meet him in Belgium in July. Then, for the

| |

| − | first time in his letters, he acknowledged the imbalance in their need for

| |

| − | each other: "My dear old Boy, I miss you more than you do me." He wondered

| |

| − | "constantly--after dark;' he confessed, "why should one go and

| |

| − | the other stay. It is rough on the one who remains"--a repeated refrain.

| |

| − | "Harry" (another dog) "sends a wave of her tail and a gentle swagger

| |

| − | of her body"--"Charles/Venus" was not the only mixed-sex dog name.

| |

| − | "Tom;' Millet added, "sends you his brightest smile and Venus wags his

| |

| − | aimless tail in greeting."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: May 30, 1875==

| |

| − | He had not "passed one good night" since they parted, Millet admitted

| |

| − | to Stoddard on May 30, and he was "completely played out from

| |

| − | want of sleep and rest." He had not mentioned it before, "and I don't dare

| |

| − | tell you why I haven't."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | What was it, exactly, that Millet dared not say? Was ~ simply that he

| |

| − | missed Stoddard too much and was depressed? Or did he believe, possibly,

| |

| − | that he had exhausted himself: in Stoddard's absence, from voluntary

| |

| − | or involuntary seminal emissions? Or, did Millet believe, perhaps, that

| |

| − | he received from Stoddard's physical presence some spiritual, or material,

| |

| − | vitality-enhancing substance? We cannot know for sure. But other evidence

| |

| − | that we will consider supports a sexual interpretation.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Whatever Millet did not say, he was also probably worrying again

| |

| − | about their unequal need for each other and about coming on too strong to Stoddard. We have already heard Stoddard's reference to two men

| |

| − | friends' "monstrous show of feeling." Displays of emotion were evidently

| |

| − | threatening, as well as intriguing, to Stoddard.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Millet had supposed for a while that it "was our old attic chamber that

| |

| − | made me restless."' and he had ordered Giovanni to move his bed elsewhere

| |

| − | in the house. He had not "been into our attic room since and don't

| |

| − | intend to go"--strong feelings about their old bedroom. But the "change

| |

| − | of room does not cure me."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | "What is the matter?" asked Millet, struggling to understand the

| |

| − | source of his distress: "I know I miss you, my old chummeke, but isn't it

| |

| − | reasonable that my other self misses you still more and cant let me sleep

| |

| − | because he wants your magnetism! I think it must be so."

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Millet was two-sided, he suggested, and one of his sides lacked the vital

| |

| − | force provided by Stoddard's physical, bodily presence. "Magnetism"

| |

| − | was a common nineteenth-century name for an individual's power to attract,

| |

| − | his force of personality, and his energy.

| |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| − | Was it possible that Millet missed, specifically, the vivifying ingestion

| |

| − | of Stoddard's spirit via oral sex? This is not as far-fetched as it may sound.

| |

| − | Three years after Millet wrote to Stoddard, in 1878, Dr. Mary Walker

| |

| − | warned readers of her popular medical manual not to believe the common

| |

| − | folklore that women's ingestion of men's semen, and men's ingestion

| |

| − | of women's vaginal secretions, promoted health, life, and beauty. The benefits of an older man ingesting a younger man's semen

| |

| − | was actually extolled by the English sex reformer Edward Carpenter to an

| |

| − | American visitor (Gavin Arthur) with whom he tested the practice in the early twentieth

| |

| − | century.

| |

| | | | |

| | + | In Sienna, Stoddard recorded, he and his companion-in-arms slept in |

| | + | a "great double bed ... so white and plump it looked quite like a gigantic |

| | + | frosted cake--and we were happy." The last phrase directly echoes |

| | + | Stoddard's favorite Walt Whitman Calamus poem in which a man's friend lies |

| | + | "sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night" -- "and that night I was happy." Sleeping happily with Millet in that cake/bed, Stoddard |

| | + | again linked food and bodily pleasure. In Sienna, Stoddard and Millet also looked at frescos by the artist nicknamed "Sodoma", Giovanni Bazzi, the outspoken 16th century artist.<ref>James Saslow is working on a book about Sodoma: see http://maps.google.com/maps?ftr=earth.promo&hl=en&utm_campaign=en&utm_medium=van&utm_source=en-van-na-us-gns-erth&utm_term=evl</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Mrs. Adams "is spooney on you, you know," Millet told Stoddard. But

| |

| − | the roaming Stoddard was not thinking about Mrs. Adams, however

| |

| − | affectionate their relationship. At long last, Stoddard admitted that he

| |

| − | missed Millet, who was extremely pleased to hear it: "Bet your life, dear

| |

| − | Boy, that it soothes me to learn that I am not the only one who misses

| |

| − | his companion in arms." ("Companion-in-arms" appears here, again, as

| |

| − | these bedfellows' private, affectionate name for each other.)

| |

| | | | |

| | + | ==Back in Venice: Spring 1875== |

| | + | Back in their Venice home in spring 1875, Stoddard recalled one day |

| | + | seeing "a tall, slender and exceedingly elegant figure approaching languidly." |

| | | | |

| − | Millet sent Stoddard "much love," declaring himself "yours to put

| + | '''Photo below: Abraham Archibald Anderson''' |

| − | your finger on" -- he was still available for the taking. Millet played Penelope,

| |

| − | stay-at-home wife, to Stoddard's wandering Odysseus.

| |

| | | | |

| | + | [[File:Anderson,A.A.jpeg|left]] |

| | | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: June 9, 1875==

| |

| − | "Since I got your last letter;' Millet reported on June 9, "I have passed

| |

| − | two good nights dreamless and waking only in the morning." Reassured

| |

| − | of Stoddard's love, he slept: "I reckon it was the influence of the letter, or

| |

| − | the prayer."

| |

| | | | |

| | + | This second American artist, A. A. Anderson, appeared one Sunday |

| | + | at Millet's wearing a "long black cloak of Byronic mold," one corner |

| | + | of which was "carelessly thrown back over his arm, displaying a lining of |

| | + | cardinal satin." The costume was enhanced by a gold-threaded, damask |

| | + | scarf and a broad-brimmed hat with tassels.<ref>Photo: page 123 in Elmer S. Dean, “A. A. Anderson, Painter and Citizen.” ''The Broadway Magazine'', May 1904, Vol. XIII, No. 2, pages 123-128. For more on Anderson see Gerald M. Ackerman, ''American Orientalists'' (Art Creation Realisation, September 1, 1994, ISBN-10: 2867700787. ISBN-13: 978-2867700781), page 270, accessed February 3, 2012 from http://books.google.com/books?id=onraQlj_C7wC&pg=PA270&lpg=PA270&dq=A.+A.+Anderson+painter+Venice+1875&source=bl&ots=AmTqc0Dk5I&sig=CC5m1fgr1tZHSxZHwAI6TRf3M-g&hl=en&sa=X&ei=eVwsT6pMyczYBae8hIEP&sqi=2&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=A.%20A.%20Anderson%20painter%20Venice%201875&f=false. Also see: Abraham Archibald Anderson. ''Experiences and Impressions: The Autobiography of Colonel A. A. Anderson''. New York, 1908.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Stoddard was still much on Millet's mind, however: The Adamses "say I am always thinking of you,"' and Millet did not deny it. But Mr. and

| |

| − | Mrs. Adams probably did not understand Millet's infatuation as sexual.

| |

| | | | |

| | + | In Stoddard's published |

| | + | memoirs, identifying Anderson only as "Monte Cristo," the journalist recalled |

| | + | the artist's "uncommonly comely face of the oriental--oval and almond- |

| | + | eyed type." Entranced by the "glamor" surrounding Monte |

| | + | Cristo, Stoddard soon passed whole days "drifting with him" in his gondola, |

| | + | or walking ashore. |

| | | | |

| − | Earlier, Millet and Stoddard had conspired with Donny Adams for her

| |

| − | to meet a young woman she idolized from afar, Julia ("Dudee") Fletcher,

| |

| − | an androgynous, aspiring writer (later, the author of the noveI Kismet, the

| |

| − | source of the musical). But Donny had decided that she was afraid to

| |

| − | meet Dudee at home-to "beard the lion in his den," as Millet put it. (Julia,

| |

| − | the lion, is an intriguing, sex-mixed metaphor). So Millet had

| |

| − | arranged to introduce Donny to Dudee on some neutral ground, and, he

| |

| − | reported, "Donny at last has met her idol!!" He hoped that Donny "has

| |

| − | not created too exalted an ideal."

| |

| | | | |

| | + | Invited to dinner by Monte Cristo, Stoddard and his friend (Millet) |

| | + | found Monte occupying the suite of a "royal princess, it was so ample and |

| | + | so richy furnished." (Monte was a "princess,"' Stoddard hints.) |

| | | | |

| − | The Donny/Dudee introduction, in

| |

| − | fact, proved a bust. A few weeks later Millet reported to Stoddard that

| |

| − | Donny "has given up the study of girls and is going to devote herself to

| |

| − | the law. A profitable change, I think."

| |

| | | | |

| | + | Funded |

| | + | by an inheritance from dad, Monte had earlier bought a steam yacht and |

| | + | cruised with an equally rich male friend to Egypt, then given the yacht |

| | + | away to an Arab potentate. Later, while Stoddard was visiting Paris, he |

| | + | found himself at once in the "embrace of Monte Cristo," recalling: "That |

| | + | night was Arabian, and no mistake!" Stoddard's reference to The Arabian Nights, |

| | + | a classic text including man-love episodes, also invoked a western mystique of "oriental" sex. |

| | | | |

| − | What, exactly, "the study of girls" meant to Donny is not clear. But

| |

| − | Donny's "interest in girls" and in men again suggests a historical fluidity

| |

| − | of libido that only later hardens into an exclusive, either/or devotion to

| |

| − | girls or boys. In 1875, neither Millet, Stoddard, nor Donny seem surprised

| |

| − | at her shift in interest from men to women.

| |

| | | | |

| | + | ==To England and Robert William Jones== |

| | + | After the beautiful Anderson left Venice, Stoddard, the perennial |

| | + | rover, found it impossible to settle down any longer in the comfortable, |

| | + | loving domesticity offered by Millet. The journalist may also have needed |

| | + | new sights to inspire the travel writing that supported him. On May 5, 1875, he therefore |

| | + | set off for Chester, England, to see Robert William Jones, a fellow with |

| | + | whom, a year earlier, he had shared a brief encounter and who had since |

| | + | been sending him passionate letters.<ref>The date that Stoddard left is cited by {{Engstrom}}, page 66.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Millet ended this letter playfully, sending Stoddard "more than the

| |

| − | sum total of the whole with a sandwich of love between the slices," bidding

| |

| − | him, "Eat & be happy." Millet's love sandwich echoed Stoddard's

| |

| − | earlier linking of food and sensual satisfaction. "Yours with all my heart;'

| |

| − | Millet signed himself.

| |

| | | | |

| | + | Stoddard's flight, after living with |

| | + | Millet for about six months, marked a new phase in their relationship. |

| | + | Millet now became the devoted pursuer, Stoddard the ambivalent pursued. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: June 10, 1875== | + | =Next: [[Jonathan Ned Katz: Francis Davis Millet and Charles Warren Stoddard, 1874-1912, PART 2]]= |

| − | But Millet's needy heart now sometimes bled for his wandering loved

| |

| − | one. A note that the artist wrote the next day concluded with a drawing

| |

| − | of a heart dripping blood, an arrow through it, and the slang query "How

| |

| − | high is that?"--meaning "What do you think of that?"

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: June 18, 1875==

| |

| − | A few weeks later, however, on June 18, Millet was telling Stoddard:

| |

| − | "You can't imagine what pleasure I take in anticipating our trip in Belgium

| |

| − | and Holland. Don't fail to come, old chummeke, and we'll have a

| |

| − | busting time."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | But, true to Millet's anxious premonition, his slippery, intimacy-shy

| |

| − | friend failed to appear in Belgium. And, by the summer of 1875, Millet

| |

| − | had run out of money and had returned to America, writing to Stoddard,

| |

| − | first from Boston, then from his parents' home in East Bridgewater,

| |

| − | Massachusetts, where he had a studio. In the States, Millet sought writing

| |

| − | and illustration work as a journalist, as well as commissions for

| |

| − | painted portraits.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: August 13, 1875==

| |

| − | In Massachusetts, Millet reported on August 13, he was "bored to

| |

| − | death" and felt himself "the prey of a thousand vulturous individuals who suck the vitality out of me in ten thousand different ways." This draining

| |

| − | of his vitality was the exact opposite of the vitality provided by Stoddard's

| |

| − | "magnetism;' and Millet's sucking metaphor may hint again at an aspect

| |

| − | of their energy interchange.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: August 15, 1875==

| |

| − | A letter from Stoddard had "brought an odor of the old country with

| |

| − | it that was refreshing in this desert," a gloomy Millet reported on August

| |

| − | 15, from East Bridgewater, a place he detested: "If there ever was a

| |

| − | soul killing place this is it. Crowds of people ... swoop down upon me

| |

| − | and bore me to death."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | If Stoddard, his "dear old fellow;' was with him, Millet imagined, "we

| |

| − | could be happy a few months and do some good work." Only his own

| |

| − | death, or his father's, could keep him in America, Millet declared dramatically, adding, "I hope for a long life for both of us yet." Intimations of mortality.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | "You know that I only feel whole when you are with me;' Millet now

| |

| − | confessed, admitting for the first time his full, profound need for Stoddard.

| |

| − | Millet then referred, again, to Stoddard's "magnetism of the soul

| |

| − | that can not be explained and had better not be analyzed." Close analysis

| |

| − | of Stoddard's magnetism was dangerous for Millet. Stoddard's magnetic

| |

| − | attraction led Millet to a humiliating pursuit of an unavailable beloved,

| |

| − | perhaps even a loss of self.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | His and Stoddard's "Venetian experience is unique;' declared Millet,

| |

| − | summing up their former romance at its height. He hoped for as good an

| |

| − | experience in the future, "if not a similar one." He still seemed to be expecting

| |

| − | a similar future intimacy with Stoddard, whom he urged to join

| |

| − | him on his travels through Europe (and, implicitly, through life): "We

| |

| − | can do the world if you keep up your courage."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet ordered Stoddard, jokingly, to "Tell Mrs Swoon" (Mrs. Adams,

| |

| − | no doubt) that he would send his photograph. But, in the meantime, he

| |

| − | enclosed for Stoddard "a crumpled proof of one as Juliette." The faded

| |

| − | proof of Millet in a long, curly, blond wig is still enclosed in his letter.

| |

| − | Playing with sex inversions was not, among these friends, limited to

| |

| − | dogs' names.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | <ADD PHOTO OF MILLET AS JULIET>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Stoddard had written earlier that if Millet did not return to Europe

| |

| − | soon, he would find a new "boy"--his tease simultaneously expressed desire

| |

| − | for Millet and suggested that he was replaceable. Once again (as documented by historians), "boy"

| |

| − | and "man" name the partners in a nineteenth-century intimacy of males,

| |

| − | though, in this case, the actual age difference was slight. Millet was Stoddard's

| |

| − | "boy" only metaphorically, and temporarily, for the younger Millet

| |

| − | usually acted the active, pursuing "man," the older Stoddard, the hard-to-get "boy."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The ever-traveling Stoddard was impossible to pin down. Millet

| |

| − | finally understood, admonishing his flighty friend: "I see indications of

| |

| − | butterflying in your threat to try another boy if I wont come back." "Butterflying"

| |

| − | was slang then for "fickleness," "inconstancy in love," or "sexual

| |

| − | unfaithfulness"; only later did the butterfly come to symbolize effeminate,

| |

| − | men-lusting men.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | "Go ahead!" (Try another boy!) Millet urged Stoddard, "You know

| |

| − | I'm not jealous, if I were I should be of Bob [Robert William Jones]. Anyone

| |

| − | who can cut me out is welcome to. Proximity is something but you

| |

| − | know I'm middling faithful."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet's faithfulness was now, for the first time, qualified, but his devotion

| |

| − | was still steady. Millet promised to write "pretty offen:' so that the

| |

| − | straying Stoddard "may not entirely forget me." He called Stoddard "my

| |

| − | windward anchor:' declaring himself "thine."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: August 25, 1875==

| |

| − | There is a "glorious sunset" but he "cannot enjoy it," a disgruntled

| |

| − | Millet complained to Stoddard on August 25, blaming his unhappiness

| |

| − | on the "the absence of the only one of my sex (or any other sex) with whom I could enjoy any beauties of nature or of art without the feeling

| |

| − | that one or both of us was a porcupine with each quill as sensitive as a bare

| |

| − | nerve."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The sex of his soulmates was not important, Millet indicated, only

| |

| − | their sharing an appreciation of nature or art. However prickly their present

| |

| − | relationship, Millet still looked to Stoddard for contentment: "If you

| |

| − | were here Charlie, I could perhaps, be happy:' He employed another

| |

| − | food/affection metaphor: "Hungry: I'd give all I possess if you were here

| |

| − | to lie down under the pines at the river side and yawn with me for a season." He ended, "With very much love," and "I am always yours."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: September 6, 1875==

| |

| − | He had spent the afternoon with Stoddard's brother Fred, Millet reported

| |

| − | on September 6, adding that Fred was a "dear fellow, wonderfully

| |

| − | like you." This resemblance, Millet knew, Charles was not happy about,

| |

| − | for the wastrel, alcoholic Fred represented the drifting Charles's worst

| |

| − | fears about his own future. Millet reassured Charles that his brother had

| |

| − | "changed very much since you saw him."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Fred, Millet again insisted, "certainly resembles you in a remarkable

| |

| − | degree in more ways than one" -- Millet intimates that Fred, like Charles,

| |

| − | was interested sexually, and perhaps exclusively, in men.

| |

| − | Insistently reminding Charles that he resembled Fred, Millet got his

| |

| − | own back against his long-courted, long-fleeing friend. He even tried to

| |

| − | incite a little jealousy: He and Fred "embraced," then spent the "whole

| |

| − | afternoon ... together," Millet reported.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet was still hoping "to have you for myself for a season in the only

| |

| − | country in the world" -- Italy. He was fantasizing about collecting a little

| |

| − | money, and buying a small house in Venice, making "an artistic place of

| |

| − | it," where Stoddard could stay, even if he was not a convert to "Bohemia." The terms "artistic" and "Bohemia" included sexual nonconformity within the iconoclasm they invoked. Millet would like to "live

| |

| − | and die in Venice," he said later.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Stoddard had reported quarreling with Mrs. Adams and her daughter

| |

| − | Donny, and Millet now commanded: "You had better make it up again

| |

| − | and spoon as before." He called Stoddard a "Don Juan" (in this context,

| |

| − | a man feminized by associating too closely with women). And, Millet

| |

| − | added, "it is plain that you need masculinizing a little--association with

| |

| − | an active broad-shouldered large-necked fellow will do it." He continued:

| |

| − | "I'm not that, but will do as a substitute in a pinch and would gladly serve

| |

| − | if you would only come in my way." Millet here played aspiring butch to

| |

| − | Stoddard's retiring femme.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: September 9, 1875==

| |

| − | Millet eagerly anticipated reconnecting with Stoddard in Europe, but warned him, in a letter of September 9, not to "go skimming way off somewhere where I can't come to." Just as he was returning to Europe,

| |

| − | Millet worried, "you will be on the move." He was "starving" for a letter,

| |

| − | he said, again looking to Stoddard for metaphorical sustenance.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | But Stoddard was busy that September, visiting Ostend, Belgium, and

| |

| − | a secluded beach called, appropriately, "Paradise;' where, as he reported

| |

| − | to the San Francisco ''Chronicle'', the bathers, "mostly males," walk "to and

| |

| − | fro in the sunshine naked as at the hour of their birth." He had also spied

| |

| − | "one or two unmistakable females trip down to the water-line in Godivahabits," as well as "two Italians--lovers possibly, and organ grinders

| |

| − | probably," who, "guileless, olive-brown, sloe-eyed, raven-haired, handsome

| |

| − | animals, male and female, hand-in-hand, strode on the sand," then

| |

| − | loosened their clothes, and "with the placid indifterence of professional

| |

| − | models ... stepped forth without so much as a fig-Ieaffor shame's sake -- a

| |

| − | new Adam and Eve."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Given Stoddard's past practice of sex-reversal, it

| |

| − | is not difficult to imagine that this Italian Adam and Eve were actually

| |

| − | Adam and Steve, two male "lovers" and "organ grinders." To "grind" had

| |

| − | meant to "copulate with" since the 1600s, so Stoddard's "organ grinders"

| |

| − | certainly signified copulating lovers.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: September 27, 1875==

| |

| − | "If you are within grabbing distance," Millet wrote on September 27,

| |

| − | imagining a hands-to-body connection, "I shall get my paws upon you

| |

| − | suddenly, you bet!"

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | He had attended a "country cattle fair," and "a great ball," where he had

| |

| − | found "lots of stunning girls but none strong enough to anchor me to this

| |

| − | country, you may write your people." Stoddard was evidently charged

| |

| − | with informing their friends of any romantic adventures that might delay

| |

| − | Millet's return, and Millet's interest in girls was apparently unremarkable

| |

| − | to this group. But Millet's ship was still tied to Stoddard, his "windward

| |

| − | anchor."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: October 19, 1875==

| |

| − | He would never have enough money to buy a house in Venice, Millet

| |

| − | despaired: "Such tight times I never experienced;' he complained on October

| |

| − | 19. Stoddard's brother also wrote to say that he, "like many others,"

| |

| − | was "out of employment." ,

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The panic of 1873, caused by unregulated speculation in railroads and

| |

| − | the overexpansion of industry, agriculture, and commerce, had weakened

| |

| − | the United States economy, which was eroded further by the contraction

| |

| − | of European demand for American farm products. The eftect of this crisis

| |

| − | was still being experienced in 1875.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | For the first time in his letters, Millet expressed anger directly at the

| |

| − | elusive Stoddard, swearing on November 15: "You D.B. [damn bastard? deadbeat?], "you haven't written me for ages you know you haven't and why? Two weeks in Munich spooning! Spooning! SPOONING! and

| |

| − | couldn't find time to write me[.] ''Che diavolo!''"

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet complained to Stoddard about a demanding visitor whose

| |

| − | three-week stay had left him "in agony." He added: "We'll have to take an

| |

| − | extra spoon to make up for all this," and confessed his own faithfulness,

| |

| − | "I haven't spooned a bit since I got back, you know l hnaven't but you, you

| |

| − | [here, he pasted a butterfly on the paper] you have had one solid spoon

| |

| − | with the Adamseseseseses and that's why I envy you." Millet's spooning

| |

| − | with Stoddard, and Stoddard's spooning with the Adamses, apparently

| |

| − | implied different sorts of spoons.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Jokingly, Millet directed his anger at Stoddard's lack of reciprocal feeling,

| |

| − | threatening him: "Now then you butterfly if you don't write more

| |

| − | I'll cut your --- off so you won't flutter about anymore." The missing

| |

| − | word is clearly "cock:' "dick:' "prick:' or some other slang term for

| |

| − | penis, and the slang suggests how the two may have talked sometimes

| |

| − | when alone. He could not speak freely in a letter, Millet several times told

| |

| − | Stoddard. Millet's threat also shows that he understood Stoddard's straying

| |

| − | as, specifically, sexual. The missing word also strongly, though indirectly,

| |

| − | suggests the sexual character of their own past relation.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: December 2. 1875==

| |

| − | "Do come up to Paris, chummeke!" Millet urged Stoddard on December

| |

| − | 2: "Come and work!" he pleaded, begging, "Come up, Charlie, do!

| |

| − | Come and spoon and ... produce something! We will live again the old

| |

| − | Bohemian [life] in a different way." They would travel together, "and live

| |

| − | as artists should in Paris. Do come!"

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet was then assisting the artist John La Farge in the decoration of

| |

| − | Trinity Church in Boston ("The romantic and picturesque details of this

| |

| − | enterprise I shall take keen delight in elaborating to you when we

| |

| − | meet.")

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | In addition, Mark Twain, a mutual friend of his and Stoddard's,

| |

| − | had come into the church and had "asked me to come to Hartford and

| |

| − | paint his portrait." Millet's artistic career was beginning to take off, and

| |

| − | he became, in a few years, a well-known artist of his day.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: January 15, 1876==

| |

| − | In his next letter, on January 15, 1876, Millet was fantasizing once

| |

| − | more about his and Stoddard's return to Venice: "If we could pass another

| |

| − | season there together I think I would not begrudge any sacrifice."

| |

| − | Financial sacrifice was Millet's obvious meaning, but emotional sacrifice

| |

| − | was implied. His feeling for Stoddard was frustrated and painful, as well

| |

| − | as sustaining.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Ending this letter with a postscript, Millet reported: "People here

| |

| − | think I am insane about a chum of mine and wonder why I don't find a

| |

| − | female attachment." The unnamed people did not expect that Millet's openly expressed, overwrought, persistent attachment to a male precluded

| |

| − | the more common attachment to a female. But even this new declaration

| |

| − | of Millet's affection provoked only silence from Stoddard, who

| |

| − | did not write again for about seven months.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The wandering Stoddard was having a jolly time. In "gay Paris," on

| |

| − | New Year's Eve, 1876, with a group of young men friends, as he reported

| |

| − | to the San Francisco ''Chronicle'', he attended a masked ball. There, those

| |

| − | who had come only "to renew our feeble but I trust virtuous indignation

| |

| − | at such sights, turn at last from the girls in boys' clothes; from the jaunty

| |

| − | sailor girl-boy who has just ridden around the room on the shoulders of

| |

| − | her captain; from the queen of darkness who swept past us in diamonds

| |

| − | and sables, and never so much as suffered her languishing eyes to rest for

| |

| − | a moment on anyone of us."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Stoddard stayed at a hotel "like a great boys'

| |

| − | boarding school," where he and the other boy-guests had pillow fights

| |

| − | while "robed in the brief garments of our sleep." With these friends he

| |

| − | hied himself to "gay halls where sin skips nimbly arm in arm with innocence

| |

| − | and verdancy," and the noisy carousers later attracted the attention

| |

| − | of a "brace of gendarmes, the handsomest and most elegant fellows in

| |

| − | Paris."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Stoddard's "gay," "girl-boy;' and "queen" are certainly sexual in

| |

| − | implication, but I do not believe they yet had the specifically "homosexual"

| |

| − | meanings they did two decades later.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: March 11, 1877==

| |

| − | In March of the following year, 1877, Millet was in Paris, and Stoddard

| |

| − | was somewhere else. On March 11, the persistent Millet was still

| |

| − | urging Stoddard to come and "occupy a room with me. I dare say I can

| |

| − | so arrange it with William who now is my bedfdlow and roommate."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: April 24, 1877==

| |

| − | On April 24, Millet again urged: "My bed is very narrow but you can

| |

| − | manage to occupy it I hope." If Stoddard did not want to share that bed,

| |

| − | "we can fix things in the study."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | In the summer of 1877 Millet was employed by several newspapers as

| |

| − | a journalist and illustrator to cover the Russian-Turkish war.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: June 29, 1877==

| |

| − | On June 29 he wrote to Stoddard: "I've seen two battles and thirst for more." "Human

| |

| − | nature;' he added, "is incomprehensible, it adapts itself much too

| |

| − | easily to circumstances." His comment applied to his affection, as well as

| |

| − | his aggressive urges. "I am quite warlike now. You wouldn't know me;'

| |

| − | he later told Stoddard.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | For the first time in his letters to Stoddard, Millet mentioned a new

| |

| − | love interest: "I am spooning frightfully with a young Greek here in

| |

| − | Oltenitza. He is a first rate fellow."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet to Stoddard: May 7, 1878==

| |

| − | Back in London on May 7, 1878, after' receiving medals for services

| |

| − | rendered to Russia, Millet for the last time addressed Stoddard as "My

| |

| − | dear Chummeke." That change in address marked the end of Millet's fantasy of live-in domesticity with Stoddard, though the two remained friends for life.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==February 19, 1879==

| |

| − | Just eight months later, on February 19, 1879, Millet wrote friends

| |

| − | about his forthcoming marriage to Elizabeth ("Lily") Greely Merrill, an

| |

| − | accomplished musician and the sister of a successful newspaper editor,

| |

| − | William Bradford Merrill.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Describing his love for Elizabeth, Millet joked

| |

| − | that he was suffering from a "malady that doesn't let go very soon when

| |

| − | it has once taken hold and the more it attacks one the more he wants."

| |

| − | This "contagion" he had caught "very badly some time ago," and "on the

| |

| − | Eleventh of march next I am going to marry Miss Merrill." Millet clearly

| |

| − | felt for Elizabeth the same strong, constant, romantic infatuation that,

| |

| − | just a few months earlier, he had still felt for Stoddard.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | On the appointed date, in Paris, Mark Twain and the foremost American sculptor of the

| |

| − | time, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, served as witnesses for the groom, and

| |

| − | showman Phineas Taylor Barnum stood as a witness for the bride. In

| |

| − | time, Millet and his wife produced three children: Kate, John Parsons,

| |

| − | and Lawrence.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Five years later, Millet fulfilled a dream, founding a Bohemian colony

| |

| − | with the painters John Singer Sargent, Alfred Parsons, and Edwin Austin

| |

| − | Abbey in the little old town of Broadway in England.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | In addition to

| |

| − | working as a journalist and an illustrator, in 1887 Millet published a

| |

| − | translation of a Tolstoy war novel (read and praised, incidentally, by Walt

| |

| − | Whitman), wrote a book about his own seventeen-hundred-mile canoe

| |

| − | trip down the Danube (1891), a book of short stories (1892), and his report

| |

| − | of the United States military expedition in the Philippines (1899).

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | In 1893, Millet was appointed Director of Decoration and Functions

| |

| − | for the World's Columbian Exhibition, in Chicago, on the grounds of

| |

| − | which he got the visiting Stoddard a room next to his own.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet received

| |

| − | major commissions for murals for the state capitols of Minnesota

| |

| − | and Wisconsin, the Baltimore Customs House, and the Cleveland Trust

| |

| − | Company. <<PHOTOS OF THOSE?>>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | He served on the American Federation of the Arts, the National

| |

| − | Commission of Fine Arts, and as director of the American Academy

| |

| − | in Rome, which he helped to found.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==1912==

| |

| − | In 1912, Millet and his close friend and Washington, D.C., roommate,

| |

| − | the bachelor Major Archie Butt, aide to President William Howard

| |

| − | Taft, booked steamer passage to the United States.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | From Southampton, Millet mailed a letter to the artist Alfred Parsons

| |

| − | describing their steamer's accommodations: "I have the best room I ever

| |

| − | had in a ship and it isn't one of the best either."

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Millet added: "Queer lot of people on the ship," in particular, "a number

| |

| − | of obnoxious ostentatious American women, the scourge of any place they infest and worse on shipboard than anywhere. Many of them carry

| |

| − | tiny dogs and lead husbands around like pet lambs. I tell you when she

| |

| − | starts out the American woman is a buster. She should be put in a harem

| |

| − | and kept there." Millet's comment seems as much a critique of class arrogance

| |

| − | and the relations of men and women as a misogynistic statement

| |

| − | on human females, and he probably did not mean this to be his last word

| |

| − | on the subject of women.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Three days after writing that letter, on the night of April 14, 1912,

| |

| − | Millet was reportedly last seen encouraging Italian women and children

| |

| − | into the lifeboats of the Titanic on which he, age 60, and Butt, age 46,

| |

| − | lost their lives.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | A joint monument to Frank Millet and Archie Butt, designed

| |

| − | by the sculptor Daniel Chester French and architect Thomas

| |

| − | Hastings, in President's Park, Washington, D.C., is described as a tribute

| |

| − | to friendship. <<PICTURE OF MONUMENT>>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Millet's Letters to Stoddard==

| |

| − | Millet's wonderful, loving letters to Stoddard were among Stoddard's papers

| |

| − | when he died in 1909, three years before Millet's death. Millet's letters

| |

| − | were then sold to Charles E. Goodspeed, a Boston dealer in books

| |

| − | and literary manuscripts, who seems to have held them off the market for

| |

| − | years because they were love letters from one man to another, and because

| |

| − | Millet, and, later, his wife, and immediate descendants were still alive.

| |

| − | The letters were again sold, finally, to another dealer in literary manuscripts,

| |

| − | from whom they were purchased by the library of Syracuse University,

| |

| − | which today preserves these precious documents.

| |

| − | | |

| | | | |

| | ==Notes== | | ==Notes== |

Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House

Adapted from Jonathan Ned Katz's book Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality (University of Chicago Press, 2001). The source citations are available in the printed edition.

Photo (right): Charles Warren Stoddard

By November 1874, the American travel journalist Charles Warren Stoddard had given up on the South Seas, the site of earlier sensual adventures recorded in coyly coded form in published articles. He was now pursuing his erotic destiny in Italy.[1]

There

in romantic, legendary Venice at the end of the year, "a young man quietly

joined me" in a box at the opera during intermission, Stoddard recalled.

"We looked at each other and were acquainted in a minute. Some

people understand one anotherer at sight, and don't have to try, either."

Stoddard's recollection of this meeting was published in Boston's National Magazine

in 1906.

Stoddard's friend was the American artist Francis Davis Millet.[2]

Stoddard was thirty-one in 1874, and Millet was twenty-eight.

During the Civil War, Millet's father,

a Massachusetts doctor, had served as a Union army surgeon, and in

1864, the eighteen-year-old Frank Millet had enlisted as a private, serving

first as a drummer boy and then as a surgeon's assistant.

Young Millet

graduated from Harvard in 1869, with a master's degree in modern

languages and literature. While working as a journalist on Boston newspapers,

he learned lithography and earned money enough to enroll in

1871 in the Royal Academy, Antwerp. There, unlike anyone before him,

he won all the art prizes the school offered and was officially hailed by the

king of Belgium.

As secretary of the Massachusetts commission to the Vienna

exposition in 1873, Millet formed a friendship with the American

Charles Francis Adams, Junior, and then traveled through Turkey, Romania,

Greece, Hungary, and Italy, finally settling in Venice to paint.

Photo (below): Francis Davis Millet. Back of photo (below): dedicated to Stoddard, February 19, 1875. In Hungarian "Emlekül" means "In memory of" and "Barátomnak" means "For my friend".[3]

At the opera, as Stoddard recalled, Millet immediately asked, "Whereare you going to spend the Winter?" He then invited Stoddard to live in his eight-room rented house at 262 Calle de San Dominico, the last residence on the north side of San Marco, next to a shipyard and the Public Garden.[4] "Why not come and take one of those rooms?" the painter offered, "I'll look after the domestic affairs" -- is this a Stoddard double entendre?

Stoddard accepted Millet's invitation,

recalling that they became "almost immediately very much better

acquainted." Did Stoddard go home with Millet that night?

The two lived together during the winter of 1874-75, though Stoddard

did not take one of the extra rooms. Millet's romantic letters to Stoddard

make it clear that the men shared a bed in an attic room overlooking the

Lagoon, Grand Canal, and Public Garden.

Lack of space did not explain

this bed sharing, and Stoddard's earlier and later sexual liaisons with men,

his written essays and memoirs, and Millet's letters to Stoddard, provide good evidence that their intimacy found active affectionate and erotic expressIon.

Though Stoddard's erotic interests seem to have focused exclusively

on men, Millet's were more fluid. In the last quarter of the nineteenth

century, Millet's psychic configuration was probably the more common,

Stoddard's exclusive interest in men the less usual. In any case, the ranging

of Millet's erotic interest between men and women was not then understood

as "bisexual", a mix of "homo" and "hetero." The hetero-homo division had not yet been invented.

Another occupant of the house was Giovanni, whom Stoddard called

"our gondolier, cook, chambermaid and errand-boy." His use of "maid"

and "boy" hint at gender doubling, and, perhaps, at sexual nonconformity.

(Giovanni's last name, not mentioned, is lost to history, typical in

masters' accounts of servants.)

That winter, Millet taught Giovanni to

prepare two classic New England dishes, baked beans and fish balls, and

during the cold months, Stoddard recalled, he and Millet dined Massachusetts

style in their warm Italian kitchen.

From the window of this kitchen in warmer weather, Stoddard recalled,

they watched "the supple figures of half-nude artisans" working in

an adjoining shipyard. It was "no wonder that we lingered over our meals

there," said Stoddard, without explaining that lingering. Visual, alimentary, and erotic

pleasures are repeatedly linked in Stoddard's and Millet's writings, as we

will see.

During the daytime, Millet painted in their home's courtyard while

Stoddard dozed, smoked, and wrote columns about Venice and other

Italian cities for the San Francisco Chronicle. They dined early and took

gondola rides at sunset.

In a newspaper column that Stoddard published

early in his relationship with Millet, the journalist wrote of "spoons" with

"my fair" (an unnamed woman) in a gondola's covered "lovers' cabin," and

of "her memory of a certain memorable sunset--but that is between us

two!" Stoddard here changed the sex of his fair one when discussing

"spooning" (kissing, making out) in his published writing. Walt Whitman also employed this literary subterfuge, changing the sex of the male who inspired a poem to a female in the final, published version.

Touring Italy: January 1875

In late January 1875, Stoddard, seeking new cities to write about for the

Chronicle, made a three-week tour of northern Italy, revising these memoirs

twelve years later for the Catholic magazine Ave Maria, published at

Notre Dame University. Stoddard wrote that his unnamed painter friend

accompanied him as guide and "companion-in-arms," a punning name

for his bed mate--the companion in his arms. This definitely intended

pun allowed Stoddard to imply more about this companionship than he

could say directly. A variety of other, barely coded references lace Stoddard's writing with allusions to eros between men.

In Padua, for example, Stoddard wrote that he and his companion were

struck by views of "lovely churches and the tombs of saints and hosts of college boys." Casually including "hosts of college boys" among the

"lovely" religious sights of Padua, and substituting "hosts of ... boys" for

the proverbial "angels," Stoddard's sacrilege-threatening run-on sentence

suggested that, to these two tourists, at least, the boys looked heavenly.

In another case, on the train to Florence, Stoddard and his companion

noticed a tall "fellow who had just parted with his friend" at a station. As

"soon as they had kissed each other on both cheeks -- a custom of the

country;' Stoddard explained to nonkissing American men, the traveler

was "hoisted into our compartment." But "no sooner did the train move

off, than he was overcome, and, giving way to his emotion, he lifted up

his voice like a trumpeter," filling the car with "lamentations." For half an

hour "he bellowed lustily, but no one seemed in the least disconcerted at

this monstrous show of feeling; doubtless each in his turn had been similarly affected."

Suggesting, slyly, that bellowing "lustily" was common among parting

men friends and represented the expression of a deep, intense, and by

no means unusual feeling, Stoddard pointed to a ubiquitous male eros,

not one limited to men of a special, unique, man-loving temperament.

Typically keeping a sharp eye out for the varieties of physically expressed

attachment between males, he also invoked Walt Whitman's poem on the

tender parting of men friends on a pier: "The one to remain hung on the

other's neck and passionately kiss'd him, / While the one to depart tightly

prest the one to remain in his arms." That poem, and Stoddard's essay,

suggest that parting provided, in the nineteenth century, a public occasion

for the physical expression of intense love between men, a custom

that had special resonance for men, like Stoddard, attracted to men.

Among the statues that Stoddard admired in Florence were "The

Wrestlers, tied up in a double-bow of monstrous muscles" -- another culturally

sanctioned icon of physical contact between, in this case, scantily

clad men.

Right: "The Wrestlers". Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

In Genoa, Stoddard recalled seeing a "captivating" painting of the

"lovely martyr" St. Sebastian, a "nude torso" of "a youth as beautiful as

Narcissus"--yet another classic, undressed male image suffused with

eros. The "sensuous element predominates," in this art work, said Stoddard,

and "even the blood-stains cannot disfigure the exquisite lustre of

the flesh."

Right: Guido Reni. "St. Sebastian." Galleria di Palazzo Rosso, Genoa, Italy.

In Sienna, Stoddard recorded, he and his companion-in-arms slept in

a "great double bed ... so white and plump it looked quite like a gigantic

frosted cake--and we were happy." The last phrase directly echoes

Stoddard's favorite Walt Whitman Calamus poem in which a man's friend lies

"sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night" -- "and that night I was happy." Sleeping happily with Millet in that cake/bed, Stoddard

again linked food and bodily pleasure. In Sienna, Stoddard and Millet also looked at frescos by the artist nicknamed "Sodoma", Giovanni Bazzi, the outspoken 16th century artist.[5]

Back in Venice: Spring 1875

Back in their Venice home in spring 1875, Stoddard recalled one day

seeing "a tall, slender and exceedingly elegant figure approaching languidly."

Photo below: Abraham Archibald Anderson

This second American artist, A. A. Anderson, appeared one Sunday

at Millet's wearing a "long black cloak of Byronic mold," one corner

of which was "carelessly thrown back over his arm, displaying a lining of

cardinal satin." The costume was enhanced by a gold-threaded, damask

scarf and a broad-brimmed hat with tassels.[6]

In Stoddard's published

memoirs, identifying Anderson only as "Monte Cristo," the journalist recalled

the artist's "uncommonly comely face of the oriental--oval and almond-

eyed type." Entranced by the "glamor" surrounding Monte

Cristo, Stoddard soon passed whole days "drifting with him" in his gondola,

or walking ashore.

Invited to dinner by Monte Cristo, Stoddard and his friend (Millet)

found Monte occupying the suite of a "royal princess, it was so ample and

so richy furnished." (Monte was a "princess,"' Stoddard hints.)

Funded

by an inheritance from dad, Monte had earlier bought a steam yacht and

cruised with an equally rich male friend to Egypt, then given the yacht

away to an Arab potentate. Later, while Stoddard was visiting Paris, he

found himself at once in the "embrace of Monte Cristo," recalling: "That

night was Arabian, and no mistake!" Stoddard's reference to The Arabian Nights,

a classic text including man-love episodes, also invoked a western mystique of "oriental" sex.

To England and Robert William Jones

After the beautiful Anderson left Venice, Stoddard, the perennial

rover, found it impossible to settle down any longer in the comfortable,

loving domesticity offered by Millet. The journalist may also have needed

new sights to inspire the travel writing that supported him. On May 5, 1875, he therefore

set off for Chester, England, to see Robert William Jones, a fellow with

whom, a year earlier, he had shared a brief encounter and who had since

been sending him passionate letters.[7]

Stoddard's flight, after living with

Millet for about six months, marked a new phase in their relationship.

Millet now became the devoted pursuer, Stoddard the ambivalent pursued.

Notes

- ↑ Adapted and republished on OutHistory without the original backnote citations from Jonathan Ned Katz's "Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House", Chapter 14, in Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pages 202-219.

- ↑ Stoddard and Millet had met earlier in Rome, according to Peter Engstrom, Francis Davis Millet: A Titanic Life (East Bridgewater, Massachusetts: Millet Studio Publishing, 2010), page 62.

- ↑ Photos: Syracuse University Library. Thanks to James Steakley for suggesting that the inscription is in Hungarian.

- ↑ The address is given by Peter Engstrom, Francis Davis Millet: A Titanic Life (East Bridgewater, Massachusetts: Millet Studio Publishing, 2010), page 60. A Google Maps view of the area is available at: http://maps.google.com/maps?ftr=earth.promo&hl=en&utm_campaign=en&utm_medium=van&utm_source=en-van-na-us-gns-erth&utm_term=evl