Jonathan Ned Katz: Francis Davis Millet and Charles Warren Stoddard, 1874-1912

Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House

Adapted from Jonathan Ned Katz's book Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality (University of Chicago Press, 2001). The source citations are available in the printed edition.

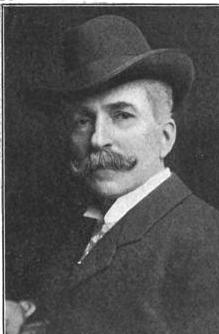

Photo (right): Charles Warren Stoddard

By November 1874, the American travel journalist Charles Warren Stoddard had given up on the South Seas, the site of earlier sensual adventures recorded in coyly coded form in published articles. He was now pursuing his erotic destiny in Italy.[1]

There

in romantic, legendary Venice at the end of the year, "a young man quietly

joined me" in a box at the opera during intermission, Stoddard recalled.

"We looked at each other and were acquainted in a minute. Some

people understand one anotherer at sight, and don't have to try, either."

Stoddard's recollection of this meeting was published in Boston's National Magazine

in 1906.

Stoddard's friend was the American artist Francis Davis Millet.[2]

Stoddard was thirty-one in 1874, and Millet was twenty-eight.

During the Civil War, Millet's father,

a Massachusetts doctor, had served as a Union army surgeon, and in

1864, the eighteen-year-old Frank Millet had enlisted as a private, serving

first as a drummer boy and then as a surgeon's assistant.

Young Millet

graduated from Harvard in 1869, with a master's degree in modern

languages and literature. While working as a journalist on Boston newspapers,

he learned lithography and earned money enough to enroll in

1871 in the Royal Academy, Antwerp. There, unlike anyone before him,

he won all the art prizes the school offered and was officially hailed by the

king of Belgium.

As secretary of the Massachusetts commission to the Vienna

exposition in 1873, Millet formed a friendship with the American

Charles Francis Adams, Junior, and then traveled through Turkey, Romania,

Greece, Hungary, and Italy, finally settling in Venice to paint.

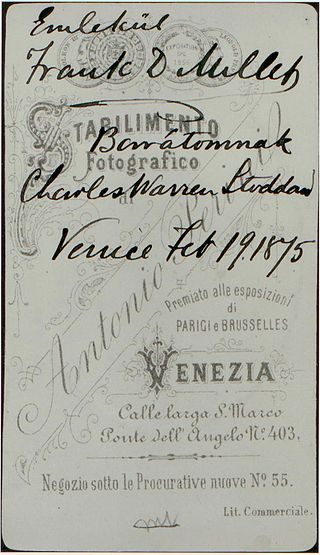

Photo (below): Francis Davis Millet. Back of photo (below): dedicated to Stoddard, February 19, 1875. In Hungarian "Emlekül" means "In memory of" and "Barátomnak" means "For my friend".[3]

At the opera, as Stoddard recalled, Millet immediately asked, "Whereare you going to spend the Winter?" He then invited Stoddard to live in his eight-room rented house at 262 Calle de San Dominico, the last residence on the north side of San Marco, next to a shipyard and the Public Garden.[4] "Why not come and take one of those rooms?" the painter offered, "I'll look after the domestic affairs" -- is this a Stoddard double entendre?

Stoddard accepted Millet's invitation,

recalling that they became "almost immediately very much better

acquainted." Did Stoddard go home with Millet that night?

The two lived together during the winter of 1874-75, though Stoddard

did not take one of the extra rooms. Millet's romantic letters to Stoddard

make it clear that the men shared a bed in an attic room overlooking the

Lagoon, Grand Canal, and Public Garden.

Lack of space did not explain

this bed sharing, and Stoddard's earlier and later sexual liaisons with men,

his written essays and memoirs, and Millet's letters to Stoddard, provide good evidence that their intimacy found active affectionate and erotic expressIon.

Though Stoddard's erotic interests seem to have focused exclusively

on men, Millet's were more fluid. In the last quarter of the nineteenth

century, Millet's psychic configuration was probably the more common,

Stoddard's exclusive interest in men the less usual. In any case, the ranging

of Millet's erotic interest between men and women was not then understood

as "bisexual", a mix of "homo" and "hetero." The hetero-homo division had not yet been invented.

Another occupant of the house was Giovanni, whom Stoddard called

"our gondolier, cook, chambermaid and errand-boy." His use of "maid"

and "boy" hint at gender doubling, and, perhaps, at sexual nonconformity.

(Giovanni's last name, not mentioned, is lost to history, typical in

masters' accounts of servants.)

That winter, Millet taught Giovanni to

prepare two classic New England dishes, baked beans and fish balls, and

during the cold months, Stoddard recalled, he and Millet dined Massachusetts

style in their warm Italian kitchen.

From the window of this kitchen in warmer weather, Stoddard recalled,

they watched "the supple figures of half-nude artisans" working in

an adjoining shipyard. It was "no wonder that we lingered over our meals

there," said Stoddard, without explaining that lingering. Visual, alimentary, and erotic

pleasures are repeatedly linked in Stoddard's and Millet's writings, as we

will see.

During the daytime, Millet painted in their home's courtyard while

Stoddard dozed, smoked, and wrote columns about Venice and other

Italian cities for the San Francisco Chronicle. They dined early and took

gondola rides at sunset.

In a newspaper column that Stoddard published

early in his relationship with Millet, the journalist wrote of "spoons" with

"my fair" (an unnamed woman) in a gondola's covered "lovers' cabin," and

of "her memory of a certain memorable sunset--but that is between us

two!" Stoddard here changed the sex of his fair one when discussing

"spooning" (kissing, making out) in his published writing. Walt Whitman also employed this literary subterfuge, changing the sex of the male who inspired a poem to a female in the final, published version.

Touring Italy: January 1875

In late January 1875, Stoddard, seeking new cities to write about for the Chronicle, made a three-week tour of northern Italy, revising these memoirs twelve years later for the Catholic magazine Ave Maria, published at Notre Dame University. Stoddard wrote that his unnamed painter friend accompanied him as guide and "companion-in-arms," a punning name for his bed mate--the companion in his arms. This definitely intended pun allowed Stoddard to imply more about this companionship than he could say directly. A variety of other, barely coded references lace Stoddard's writing with allusions to eros between men.

In Padua, for example, Stoddard wrote that he and his companion were

struck by views of "lovely churches and the tombs of saints and hosts of college boys." Casually including "hosts of college boys" among the

"lovely" religious sights of Padua, and substituting "hosts of ... boys" for

the proverbial "angels," Stoddard's sacrilege-threatening run-on sentence

suggested that, to these two tourists, at least, the boys looked heavenly.

In another case, on the train to Florence, Stoddard and his companion

noticed a tall "fellow who had just parted with his friend" at a station. As

"soon as they had kissed each other on both cheeks -- a custom of the

country;' Stoddard explained to nonkissing American men, the traveler

was "hoisted into our compartment." But "no sooner did the train move

off, than he was overcome, and, giving way to his emotion, he lifted up

his voice like a trumpeter," filling the car with "lamentations." For half an

hour "he bellowed lustily, but no one seemed in the least disconcerted at

this monstrous show of feeling; doubtless each in his turn had been similarly affected."

Suggesting, slyly, that bellowing "lustily" was common among parting

men friends and represented the expression of a deep, intense, and by

no means unusual feeling, Stoddard pointed to a ubiquitous male eros,

not one limited to men of a special, unique, man-loving temperament.

Typically keeping a sharp eye out for the varieties of physically expressed

attachment between males, he also invoked Walt Whitman's poem on the

tender parting of men friends on a pier: "The one to remain hung on the

other's neck and passionately kiss'd him, / While the one to depart tightly

prest the one to remain in his arms." That poem, and Stoddard's essay,

suggest that parting provided, in the nineteenth century, a public occasion

for the physical expression of intense love between men, a custom

that had special resonance for men, like Stoddard, attracted to men.

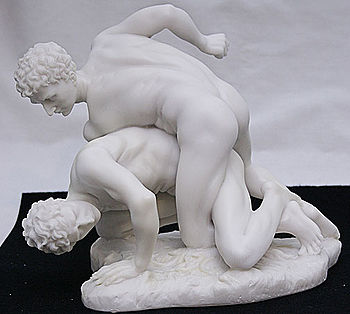

Among the statues that Stoddard admired in Florence were "The

Wrestlers, tied up in a double-bow of monstrous muscles" -- another culturally

sanctioned icon of physical contact between, in this case, scantily

clad men.

Right: "The Wrestlers". Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

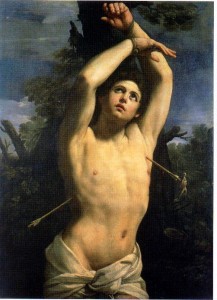

In Genoa, Stoddard recalled seeing a "captivating" painting of the

"lovely martyr" St. Sebastian, a "nude torso" of "a youth as beautiful as

Narcissus"--yet another classic, undressed male image suffused with

eros. The "sensuous element predominates," in this art work, said Stoddard,

and "even the blood-stains cannot disfigure the exquisite lustre of

the flesh."

Right: Guido Reni. "St. Sebastian." Galleria di Palazzo Rosso, Genoa, Italy.

In Sienna, Stoddard recorded, he and his companion-in-arms slept in a "great double bed ... so white and plump it looked quite like a gigantic frosted cake--and we were happy." The last phrase directly echoes Stoddard's favorite Walt Whitman Calamus poem in which a man's friend lies "sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night" -- "and that night I was happy." Sleeping happily with Millet in that cake/bed, Stoddard again linked food and bodily pleasure. In Sienna, Stoddard and Millet also looked at frescos by the artist nicknamed "Sodoma", Giovanni Bazzi, the outspoken 16th century artist.[5]

Back in Venice: Spring 1875

Back in their Venice home in spring 1875, Stoddard recalled one day seeing "a tall, slender and exceedingly elegant figure approaching languidly."

Photo below: Abraham Archibald Anderson

This second American artist, A. A. Anderson, appeared one Sunday

at Millet's wearing a "long black cloak of Byronic mold," one corner

of which was "carelessly thrown back over his arm, displaying a lining of

cardinal satin." The costume was enhanced by a gold-threaded, damask

scarf and a broad-brimmed hat with tassels.[6]

In Stoddard's published

memoirs, identifying Anderson only as "Monte Cristo," the journalist recalled

the artist's "uncommonly comely face of the oriental--oval and almond-

eyed type." Entranced by the "glamor" surrounding Monte

Cristo, Stoddard soon passed whole days "drifting with him" in his gondola,

or walking ashore.

Invited to dinner by Monte Cristo, Stoddard and his friend (Millet)

found Monte occupying the suite of a "royal princess, it was so ample and

so richy furnished." (Monte was a "princess,"' Stoddard hints.)

Funded

by an inheritance from dad, Monte had earlier bought a steam yacht and

cruised with an equally rich male friend to Egypt, then given the yacht

away to an Arab potentate. Later, while Stoddard was visiting Paris, he

found himself at once in the "embrace of Monte Cristo," recalling: "That

night was Arabian, and no mistake!" Stoddard's reference to The Arabian Nights,

a classic text including man-love episodes, also invoked a western mystique of "oriental" sex.

To England and Robert William Jones

After the beautiful Anderson left Venice, Stoddard, the perennial rover, found it impossible to settle down any longer in the comfortable, loving domesticity offered by Millet. The journalist may also have needed new sights to inspire the travel writing that supported him. On May 5, 1875, he therefore set off for Chester, England, to see Robert William Jones, a fellow with whom, a year earlier, he had shared a brief encounter and who had since been sending him passionate letters.[7]

Stoddard's flight, after living with

Millet for about six months, marked a new phase in their relationship.

Millet now became the devoted pursuer, Stoddard the ambivalent pursued.

Next: Jonathan Ned Katz: Francis Davis Millet and Charles Warren Stoddard, 1874-1912, PART 2

Notes

- ↑ Adapted and republished on OutHistory without the original backnote citations from Jonathan Ned Katz's "Empty Chair, Empty Bed, Empty House", Chapter 14, in Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pages 202-219.

- ↑ Stoddard and Millet had met earlier in Rome, according to Peter Engstrom, Francis Davis Millet: A Titanic Life (East Bridgewater, Massachusetts: Millet Studio Publishing, 2010), page 62.

- ↑ Photos: Syracuse University Library. Thanks to James Steakley for suggesting that the inscription is in Hungarian.

- ↑ The address is given by Peter Engstrom, Francis Davis Millet: A Titanic Life (East Bridgewater, Massachusetts: Millet Studio Publishing, 2010), page 60. A Google Maps view of the area is available at: http://maps.google.com/maps?ftr=earth.promo&hl=en&utm_campaign=en&utm_medium=van&utm_source=en-van-na-us-gns-erth&utm_term=evl

- ↑ James Saslow is working on a book about Sodoma: see http://maps.google.com/maps?ftr=earth.promo&hl=en&utm_campaign=en&utm_medium=van&utm_source=en-van-na-us-gns-erth&utm_term=evl

- ↑ Photo: page 123 in Elmer S. Dean, “A. A. Anderson, Painter and Citizen.” The Broadway Magazine, May 1904, Vol. XIII, No. 2, pages 123-128. For more on Anderson see Gerald M. Ackerman, American Orientalists (Art Creation Realisation, September 1, 1994, ISBN-10: 2867700787. ISBN-13: 978-2867700781), page 270, accessed February 3, 2012 from http://books.google.com/books?id=onraQlj_C7wC&pg=PA270&lpg=PA270&dq=A.+A.+Anderson+painter+Venice+1875&source=bl&ots=AmTqc0Dk5I&sig=CC5m1fgr1tZHSxZHwAI6TRf3M-g&hl=en&sa=X&ei=eVwsT6pMyczYBae8hIEP&sqi=2&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=A.%20A.%20Anderson%20painter%20Venice%201875&f=false. Also see: Abraham Archibald Anderson. Experiences and Impressions: The Autobiography of Colonel A. A. Anderson. New York, 1908.

- ↑ The date that Stoddard left is cited by Peter Engstrom, Francis Davis Millet: A Titanic Life (East Bridgewater, Massachusetts: Millet Studio Publishing, 2010), page 66.