Difference between revisions of "Gay Activists Alliance"

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

| − | '''Michael Lavery, a [[Gay Liberation Front]] member who later joined GAA, thought that some of the organization's political success came from its reputation as the moderate alternative to GLF.''' [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHAGRFPFqqs| Lavery talks in a video interview] | + | '''Michael Lavery, a [[Gay Liberation Front]] member who later joined GAA, thought that some of the organization's political success came from its reputation as the moderate alternative to GLF.''' [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHAGRFPFqqs| '''Lavery talks in a video interview'''] |

| − | |||

===Intro 475=== | ===Intro 475=== | ||

Latest revision as of 11:54, 28 September 2011

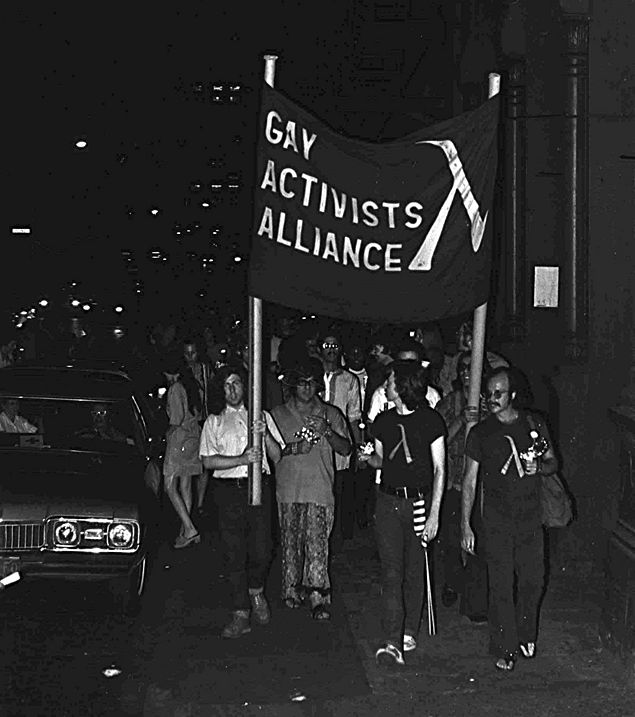

This page focuses on the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), a militant, non-violent civil rights group organized by Jim Owles, Marty Robinson, Arthur Evans, Arthur Bell, and eight others in December of 1969. The Gay Activists Alliance was the longest-lasting group formed in the gay liberation era, and helped to give rise to the confrontational yet reform-oriented movement that is still prevalent today.

Structure

Many of the founders of the Gay Activists Alliance had participated in the Gay Liberation Front(GLF), and GAA was formed largely out of their dissatisfaction with the structure, goals, and political philosophy of GLF. They worked hard to develop a group that would avoid the flaws they had seen in GLF.

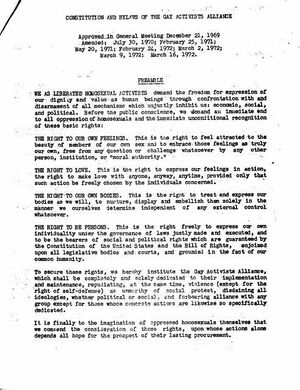

Unlike the Gay Liberation Front, which instituted no formal structure and operated by consensus, the Gay Activists Alliance ran by parliamentary procedure and Robert’s Rules of Order. The group developed a constitution—approved on December 21st, 1969—that gave it “a continuity of values and ideals” that no one member could change.[1] GAA also instituted membership requirements and elected officers, whose duties were clearly laid out in the constitution.[2]

Like GLFers, the founders of GAA were interested in ensuring that all members had a voice in the organization. In fact, their structure was intended to achieve just that. In a pamphlet, the organization explained that its structure would provide “a greater deal of freedom than no structure at all. Personal fights or ideological diatribes are less likely to develop. Everyone has his or her say—not merely the loudest or most charismatic members.”[3] What’s more, parliamentary procedure ensured that any decisions made by the entire membership were binding on the organization, preventing the endless debates and disruptions that had characterized GLF.[4] The structure was also expedient, ensuring “...that policy decisions are mutually consistent, arrived at democratically, and carried out efficiently.”[5]

GAA developed a range of committees to execute much of the actual work of the organization. The committees—which eventually focused on issues as wide-ranging as finance, social activities, legal strategy, agit/prop, and the arts—allowed members to pursue their own interests.[6] At the same time, committees reported to the general membership and could not act without the approval of the entire group, preventing them from becoming “independent entities” like GLF’s cells.[7]

Political Philosophy

In order to attract people of all backgrounds and political persuasions while avoiding the kinds of debates that had crippled GLF, the Gay Activists Alliance was a single-issue organization.[8] Individual members could—and often did—participate in actions for other groups, but the organization as a whole focused on “mak[ing] noticeable changes in their lives as gays.”[9]

Rich Wandel, who later became president of GAA, talks about the group's one-issue focus

The Gay Activists Alliance was also reform-oriented. The founders of GAA agreed with the Gay Liberation Front that their oppression was the result of “economic, political, and social” structures.[10]But where GLF had focused on bringing about a new society, GAA looked to change the system as it stood. Although conceding that “the political system is corrupt and inefficient,” the group also recognized that “it remain[ed] vulnerable to militant confrontation tactics.” As a matter of pragmatism, GAA “…would be foolish not to exploit it.”[11]

The group promised to confront the system—militantly but non-violently—to bring about “an immediate end to all oppression of homosexuals.”[12]

Zaps

GAA may have utilized the political system, but it was not seeking to accommodate it. The group practiced “confrontation politics”—in which politicians or other “persons of authority” were “publicly exposed through mass demonstrations, disruption meetings, and sit-ins.”[13] Zaps, as these actions came to be known, forced politicians to take a stand on gay rights (or at least publicized their unwillingness to do so); proved that gay people were a “legitimate political minority” and a force to be reckoned with; and facilitated “the development of an open sense of public identity in the gay community” that would encourage others to follow suit.[14]

To ensure they had a far-reaching impact, zaps were meant to grab the attention of the media. As such, they were often lively affairs. To push Mayor John Lindsay to make a public statement in support of gay rights, for example, GAAers planted themselves in the audience at a taping of his weekly television show, a reporter from the Village Voice in tow. During the show, GAA leader Arthur Evans “rushed to the platform: ‘What about homosexuals? Homosexuals want an end to job discrimination.’” Although Evans was removed by security, the other Activists in the room continued the disruption. They “clapped, stomped, and chanted: ‘Answer the homosexual!’” as he was led out. Lindsay plastered a smile on his face for the next half hour as the audience continued to press him: “‘What about the laws against sodomy? We want free speech! Lindsay, you need our votes. Homosexuals account for 10 per cent of the vote….’”[15] Although the Mayor’s camera crew stopped recording, an account of the entire affair was published in the Voice and GAA won a meeting with Deputy Mayor Richard Aurelio to discuss their demands. The Mayor continued to refuse to issue a statement in favor of gay rights legislation, but GAA was nonetheless pleased that “[t]he police were kept busy and so was Lindsay’s smile.”[16]

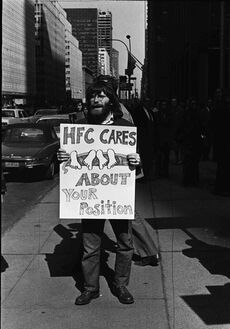

GAA didn’t just target politicians. When the president of Fidelifacts—an investigating agency “used by businesses to identify and exclude homosexuals”—explained that he “[went] on the rule of thumb that if one looks like a duck, walks like a duck, associates only with ducks, and quacks like a duck, he probably is a duck,” GAA decided to strike back.[17] The group, armed with squeaking rubber duckies, picketed Fidelifacts’ headquarters. At the front of the picket line was Marty Robinson—dressed like a duck. The protest was designed not only to grab the eye of the media and highlight employment discrimination against homosexuals, but also to inspire closeted gays and lesbians to join in the fun.[18]

Rich Wandel talks in a video interview about his favorite zap

Other Political Tactics

Beyond Zaps, GAA utilized an array of tactics to gain political support. During the 1970 elections, for example, they invited candidates to speak at their general meetings, lobbied at the New Democratic Coalition’s convention, and ran voting drives in the gay community.[19] They sent out questionnaires to candidates soliciting their stances on a range of issues, from sodomy laws and police entrapment to employment and income tax discrimination.[20] And while the group didn’t endorse politicians, it did make sure that the gay community—and the media—were well aware of their views, issuing press releases, publishing articles in gay newspapers, and leafleting in areas populated by gays and lesbians.[21]

Along the way, GAA made sure to stress that homosexuals were a powerful voting bloc. As one tenth of the population, gays and lesbians could have a significant impact on the direction each election went—a fact GAAers didn’t let politicians forget.[22] They urged gays and lesbians to “put gay power to the voting booth” and “vote gay,” while reminding politicians that public statements in support of gay rights could “provide a considerable vote swing” and help them win elections.[23]

Their strategy often worked. In the 1970 election, 40 candidates responded to the GAA questionnaire, all but one of them positively.[24] The group elicited supportive statements from the gubernatorial candidate and both senatorial candidates—the first in New York State to come out in favor of gay rights. [25] The majority of the pro-gay candidates (many of whom GAA canvassed for) won their elections; the organization made sure to publicize the difference its support had made.[26]

Michael Lavery, a Gay Liberation Front member who later joined GAA, thought that some of the organization's political success came from its reputation as the moderate alternative to GLF. Lavery talks in a video interview

Intro 475

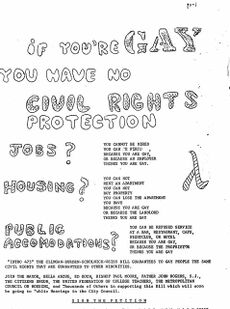

As early as the spring of 1970, GAA decided to focus much of its political energies on pushing for gay rights legislation in the New York City Council. The organization contended that such a bill would appeal to—and help politicize—a wide range of homosexuals.

Additionally, it would gain the support of influential community leaders and politicians who could “help legitimize homosexuals as a political minority.”[27] Finally, it would expose gays and straights alike to the level of systematic discrimination that homosexuals faced in employment, housing, and public accommodations.[28] Although the bill’s passage was not necessary to achieve these goals, if it became law it also had the potential to make real changes in the lives of New York City’s gay and lesbian residents.

GAAers worked furiously throughout 1970 to secure council members willing to introduce the legislation, develop a strategy for their legislative push, and document their discrimination for a report to present to the City Commission on Human Rights.[29]

On January 6, 1971, Council Members Carter Burden and Eldon Clingan introduced a bill—Intro 475—to include sexual orientation in New York’s Human Rights Law. GAA immediately put its legislative strategy into action. The group attacked from two sides: members of the Municipal Government Committee worked behind-the-scenes to gain the support of council members, and the Municipal Fair Employment Committee organized public demonstrations that would put pressure on obstinate politicians while encouraging other gays and lesbians to come out and join the fight.[30]

The group faced difficulties from the beginning. Although some influential politicians backed the bill, Mayor Lindsay continued to refuse to publicly support it or issue an Executive Order banning discrimination within the City. At the same time, the Council’s Majority Leader, Thomas Cuite, and the Chairman of the General Welfare Committee, Saul Sharison, rebuffed GAA’s demands to schedule public hearings.[31]

As time wore on, playful demonstrations like the Fidelifacts zap gave way to more confrontational actions. In October 1971, a late-night protest at Sharison’s apartment building, for example, quickly turned “nightmarish” when the Tactical Police Force—“the city’s most brutal cops”—began to “savagely” beat demonstrators.[32] Nevertheless, the action seemed to work. Sharison scheduled public hearings for Intro 475 five days later.[33]

The hearings only brought more confrontations. Insulting statements from council members provoked GAAers, who loudly voiced their objects by calling them “heterosexual bastards” and “bigots.”[34] While Lindsay enlisted an aide to read a statement of support on the second day of the hearings, he refused to allow the police and fire commissioners to testify—leading GAA to declare “TOTAL WAR” on the Mayor.[35]

On January 27, 1972, the General Welfare Committee voted against bringing Intro 475 to the full council. But while the bill failed, GAA achieved its goals of raising awareness about discrimination against homosexuals and encouraging more gays and lesbians to fight against their oppression. Intro 475, as GAA leader Marty Robinson wrote in an article for the Village Voice, “was not advocated as the goal for the movement but as a tactic, a tool toward liberation…. In that very real sense, Intro 475 never was and never could be defeated. Many gays came out of the closet for the struggle and many more will join them as that struggle continues.”[36]

Rich Wandel talks in a video interview about the importance of Intro 475

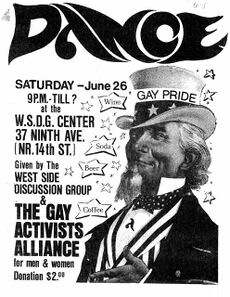

A New Gay Culture

More than just interested in making political gains for gays and lesbians, the Gay Activists Alliance also strove to alter a mainstream culture permeated by sexism and homophobia—and to create a “liberated gay culture…free of the oppressive role-playing of a hostile sexist society.”[37]

Never interested in “legal reform as an end in itself,” the group saw its single-issue focus and confrontational tactics as an important way to encourage others to come out of the closet and promote “Gay Power…Gay community spirit…[and] Gay togetherness.”[38] In addition, GAAers targeted culture makers like The Tonight Show and Harper’s Magazine to ensure that the mass media promoted a positive image of gays and lesbians.[39]

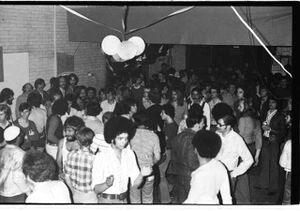

GAA organized a range of activities—such as dances, film screenings, plays, yoga classes, and Consciousness-Raising groups—that were intended to bring gays and lesbians together while helping them understand their oppression, transform their personal interactions, and develop a new gay culture free from gender and sexual constraints.[40] The group also used these events to politicize gays and lesbians, sometimes ending dances with a call to participate in a demonstration that night.[41]

One of GAA’s greatest achievements was securing a space that gays and lesbians could call home. In April 1971, the group leased an abandoned firehouse on Wooster Street in Soho. The Firehouse spurred the development of many of the committees responsible for culture-building activities, and allowed the group to host events (such as weekly dances) that were difficult to put on without a regular space. The Firehouse had implications beyond GAA, however. It also served as a center for New York’s gay community and helped to give rise to a new gay and lesbian culture—in the form of bars, coffee shops, bookstores, and more—that would erupt in the years to come.[42]

Michael Lavery remembers in a video interview being "in awe" of the Firehouse

The Lesbian Liberation Committee

The Gay Activists Alliance worked hard to create a diverse group that represented the entire gay community, but the organization was largely dominated by men. To increase the presence of women in GAA, a number of women members formed a subcommittee of the Community Relations Committee. As the subcommittee began achieving greater success (a film festival it hosted in the fall of 1971 brought in more than 100 women), its members pushed to form their own committee. Many men worried that a separate lesbian committee would tear at GAA’s unity, but the women prevailed. In the fall of 1971, they formed the Lesbian Liberation Committee (LLC).[43]

LLC set out to politicize lesbians and bring more women into the group. Arguing that women participated less in gay political activity because they had yet to develop a strong lesbian identity, LLC wanted to carve out a space where women could meet and create “a sense of community.”[44]

The Committee’s activities were thus largely social. It sponsored screenings of films that were “of special interest to Lesbians,” organized panel discussions on topics like coming out and lesbian motherhood, and hosted all-women’s dances and picnics.[45]

The women who organized LLC were committed gay liberationists more interested in attracting women to the Gay Activists Alliance than participating in separate lesbian feminist activism.[46] But over time, members of LLC increasingly clashed with men in GAA, leading many of them to question their place in the organization. Jean O’Leary, who was a chair of LLC, remembered: “We had arguments every single day. We had debates on the floor. The men were listening, but they just weren’t hearing what we had to say, and they held on to their stereotyped views of women. They would also make a point of crashing our women-only events.”[47]

O’Leary urged the women to form a separate organization. Although many resisted, after months of discussions and debates, they left GAA.[48] In the spring of 1972, they formed Lesbian Feminist Liberation (LFL)—a structured, reform-oriented group that focused on finding freedom for lesbians while maintaining alliances with other gay and feminist groups.[49]

The creation of LFL had as much to do with the sexism women faced in GAA as with their desire to focus on their own needs and experiences as lesbian women. O’Leary recalled: “We had to find ourselves as a group....Just as gay people have had to become visible in society, lesbians had to become visible within the gay community, as well as in the larger society.”[50]

Disbandment

The Gay Activists Alliance remained in existence until 1981, making it the longest-lasting group created during the heyday of gay liberation. Members of GAA also helped to establish gay rights organizations—such as the National Gay Task Force (co-founded by GAA President Bruce Voeller in 1973) and Lambda Legal (co-founded by Michael Lavery in the same year)—that continue to struggle for gay and lesbian equality today.

Return to Gay Liberation in New York City.

Categories

Gay Liberation, New York City, Gay Activists Alliance, Zaps, Intro 475, Clingan-Burden Bill, Lesbian Liberation Committee, Lesbian Feminist Liberation

Contact

Lindsay Branson: lindsay.branson@gmail.com

References

- ↑ “The GAA Alternative,” 2, (#3) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives, Brooklyn, NY; “Constitution and Bylaws of the Gay Activists Alliance,” Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ “Gay Activists Alliance Membership Application,” (#3) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives; Arthur Bell, Dancing the Gay Lib Blues (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971), 23; “Constitution and Bylaws of the Gay Activists Alliance.”

- ↑ “The GAA Alternative,” 3.

- ↑ Toby Marotta, The Politics of Homosexuality (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 143.

- ↑ “What is GAA?” September 1971, Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ “GAA Committees and Services,” Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives, Brooklyn, NY.

- ↑ “The GAA Alternative,” 4.

- ↑ “What is GAA?”

- ↑ ”The GAA Alternative,” 5.

- ↑ “Constitution and Bylaws of the Gay Activists Alliance.”

- ↑ “The GAA Alternative,” 6.

- ↑ “Constitution and Bylaws of the Gay Activists Alliance.”

- ↑ ”What is GAA?”

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 147; “What is GAA?”

- ↑ Sandra Vaughn, “Lindsay & Homosexuals: An Edited Encounter,” Village Voice, April 23, 1970, p. 8. Quoted in Marotta, Politics, 155; “Gays Crack Mayor’s Shield,” (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ “Gays Crack Mayor’s Shield,” (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives; Bell, Dancing the Gay Lib Blues, 56-7.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 204-5.

- ↑ Ibid.; Morty Manford, interview by Eric Marcus, Making Gay History (New York: Perennial, 2000), 142-3; Rich Wandel, personal interview, February 14, 2010.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 159.

- ↑ Teal, Gay Militants, 253-5.

- ↑ “Statement from Jim Owles on behalf of Gay Activists Alliance,” October 24, 1970, (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives; Kay Lahusen, Making Gay History, 139; Teal, Gay Militants, 257-62.

- ↑ “The Issue: Gay Rights,” (#3) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ Flier publicizing the views of political candidates, (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ, Lesbian Herstory Archives; “Statement from Jim Owles on behalf of Gay Activists Alliance.”

- ↑ Gay Activists Alliance Press Release, October 24, (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ Bell, Dancing the Gay Lib Blues, 139; Marotta, Politics, 160.

- ↑ Teal, Gay Militants, 262-3

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 196.

- ↑ Ibid., 198; Manford, Making Gay History, 142.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 196. See also: “Fair Employment,” a flier soliciting “information and testimony regarding anti-gay employers to present to the CITY COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS public hearings in late October.” (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives. Emphasis in original.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 202-3.

- ↑ Ibid., 206.

- ↑ Peter Fisher, The Gay Mystique (New York: Stein and Day, 1972), 162-63. Quoted in Marotta, Politics, 214-5; “Justice!” (#3) Gay Activists Alliance of NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 215.

- ↑ Ibid., 219-21.

- ↑ Ibid., 223.

- ↑ Marty Robinson, “Trashing of Intro 475: The Closet of Fear,” Village Voice, February 17, 1972, p. 18. Quoted in Marotta, Politics, 225-6.

- ↑ ”The GAA Alternative,” 5.

- ↑ Ibid., 7 and 5; “Albany March for Gay Rights, ” (#3) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ “Johnny Does it Again!” (#3) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives; “Gay Activists Alliance Invades Harper’s Magazine,” October 27, 1970, (#2) Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ ”What is GAA?”; “Gay Committees and Services”; “The GAA Alternative,” 5.

- ↑ "Justice!”

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 193-4.

- ↑ Ibid., 276-7.

- ↑ “GAA Committees and Services,” Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives; Marotta, Politics, 277.

- ↑ “The Lesbian Liberation Committee,” Gay Activists Alliance NY & NJ Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ Teal, Gay Militants, 189. The Committee even served as a sort of “liason [sic] between GAA and the lesbian groups in the community.” See: “GAA Committees and Services.”

- ↑ Jean O’Leary, Making Gay History, 154.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 283-4.

- ↑ O’Leary, Making Gay History, 154. Emphasis in original.