Gay Liberation Front

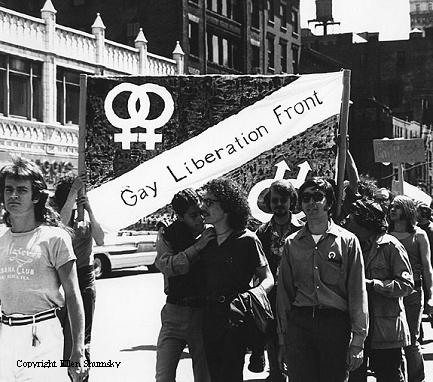

This page focuses on the Gay Liberation Front, a group of radical and revolutionary gays and lesbians that was formed in July of 1969. The first group to be organized after Stonewall, the Gay Liberation Front sparked a radical and confrontational movement that soon spread around the city and across the nation.

Origins of a Movement

Within a month after the rebellion at the Stonewall Inn, gays and lesbians organized a new group: the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). GLF tapped into the radical sentiments brewing among young, countercultural, and political gays and lesbians in New York City—and mobilized the energy and eagerness for political action that many felt in the days following Stonewall.

Radical gays and lesbians had little affinity to the Mattachine Society of New York (MSNY), the civil rights group that had dominated the gay political scene before Stonewall. After the rebellion, MSNY seemed even more out of touch as it urged gays and lesbians to temper their demands, avoid more uprisings, and continue working within the system to achieve reform.

Although some budding gay liberationists attempted to work within Mattachine through its recently formed Action Committee, they found themselves increasingly at odds with the organization’s reformist priorities. When MSNY President Dick Lietsch objected to the group’s public support of a Black Panther rally at the Women’s House of Detention, Committee members decided to rename themselves. Soon, they separated completely from Mattachine to form an entirely new group: the Gay Liberation Front.[1]

GLFer Jerry Hoose talks about the group's first meeting

Developing New Political Theories and Tactics

The Gay Liberation Front sought to avoid many of the pitfalls they saw in the political tactics of homophile groups like Mattachine. Where MSNY had attempted to integrate gays and lesbians into existing structures, GLFers would work to bring about the development of an entirely new society; and where homophile activists had sought to project an image of respectability, the new gay liberationists would fight against mainstream attitudes and values. They would “start demanding, not politely requesting, our rights.” [2]

But GLF was interested in much more than rights, advocating direct action against the system to tear down restrictive sex roles and bring about the liberation of all oppressed people. As GLFers set about achieving their freedom, almost nothing seemed out of reach. They attacked not only the “rotten, dirty, vile, fucked-up capitalist conspiracy” responsible for their own and others' oppression, but also a range of social and political institutions, such as the educational system, organized religion, the nuclear family, psychiatry, business, the media, and the mafia-run bars.[3]

Just as important, gay liberationists were interested in transforming sexuality as they knew it. As the name of the group’s newspaper—Come Out!—suggests, GLFers did not hide or feel ashamed of their sexuality. They claimed it publicly, and they urged others to do the same. What’s more, they argued that sexuality was more fluid than the current system allowed.[4] GLF aimed to create a society free not only from sexism and homophobia but also from sexual labels themselves.[5]GLFer Jim Fouratt, for example called on others to "...off the word homosexual!" asserting that such "...artificial categories defining human sexuality" served "to protect and perpetuate the institutions and systems in power whose end result is only to dehumanize life."[6]

GLFers were interested in more than just changing social institutions and norms, though; they wanted to revolutionize their own sexual interactions and relationships. They objected to the “lookism,” role-playing, and objectification they saw in the traditional gay subculture—sometimes “liberating” gay bars by dancing in multi-gendered groups rather that same-sex pairs.[7] They attempted to develop new forms of sexuality that were “sensual,” “egalitarian and mutual,” and nonmonogamous. [8] And they saw gays and lesbians, who had already broken with conventional gender roles, as uniquely poised to develop these types of relationships.[9]

Through small Consciousness-Raising groups, communes, and living collectives, GLFers confronted their own “hang ups” and sexist attitudes while developing new models for creating families and interacting with each other.[10]

(Structureless) Structure

As much as its theories, the Gay Liberation Front’s structure distinguished it from previous gay political groups. GLF considered itself “… a movement, not a static organization.”[11] As such, the group eschewed hierarchical structures, preferring an unstructured form of organization. One member explained that the weekly meetings were “…open forums, there are no dues, no donations, no membership fees. GLF has no President, no Officers, no Leaders. GLF is You...” [12]

Taking its lead from the women’s liberation movement, GLFers attempted to develop organizational forms that would allow them—in the words of historian Toby Marotta—“to embody the principles of participatory democracy and humane community which they advocated.”[13] The group operated on consensus to ensure that everyone’s opinion counted and rotated meeting chairs so that more privileged, articulate, or experienced individuals wouldn’t dominate the group

The Gay Liberation Front also utilized a cellular form, which allowed individual members to come together in small groups around their own interests and ideologies, and which gave voice to the “many mentalities, dispositions, and persuasions” the existed in GLF.[14] Cells operated independently from the rest of the group, and allowed for a wide range of activities. Among others, the 28th of June Cell published the newspaper Come Out!; the Aquarius Cell raised funds for a community center by organizing dances and other cultural activities; and the Red Butterfly Cell operated a Marxist study group.

GLFers also organized small Consciousness-Raising groups, which gave members the opportunity to share their personal experiences as a means of understanding the ways they were oppressed and exploring how they perpetuated the oppression of others.

A number of GLFers remember the group’s structure as chaotic, and at times infuriating. Anyone who came to a Sunday night meeting was considered a "member in good standing", making it easy for the same debates to drag on for weeks and months at a time. But for many, the process was exhilarating. GLFers were breaking new ground, pioneering not only new political theories but also new organizational forms that were just as important to their quest for liberation.[15]

GLFers Karla Jay and Jerry Hoose remember the GLF meetings

Dancing their way to Liberation: GLF Dances

As GLFers fought to overthrow repressive social institutions, they also sought to develop a new gay culture. They published a newspaper, Come Out!; hosted communal dinners to nurture familial ties among members; and raised funds for a community center that would provide a space for gays and lesbians to gather and hold their own meetings and events.[16]

Weekly dances were one of GLF’s most important culture-building—and fundraising—activities. The dances provided gays and lesbians with their own social space away from the oppressive atmosphere of the mafia-run bars. Bar owners often hiked up the price of (usually watered-down) drinks, which they intimidated customers into buying. The spaces were gender-segregated and populated by gays and lesbians who took on butch/femme roles or who seemed to sexually objectify each other—practices that GLFers wanted to move away from. Dancing between same-sex couples was not always allowed, and the fear of a police raid was ever present.[17]

By contrast, GLF dances were open to men and women, and encouraged dancing in singles, groups, or pairs. The suggested entrance fee was $2.50, but everyone was welcomed regardless of their ability to pay. Beer and soda were only 25 cents. The dances were far from mellow. They often featured strobe lights, go-go dancers, “frantic rock and acid rock,” though lounges were available for those who needed a break. “At a dance,” one reveler explained, “the vibrations are certainly a lot better than at a bar.”[18]

[These aspects of the dances, as well as the fact that they were overwhelmingly male, led lesbians to push for their own dances in the spring of 1970. Eventually many of them would also form their own group, Radicalesbians.]

Organizing the dances wasn’t always easy. When the group submitted an ad for its first dance to the Village Voice, the paper refused to print the heading “Gay Community Dance,” arguing that the word ‘gay’ was obscene. (The paper also objected to the heading “Gay Power to Gay People” in a call for submissions to Come Out!) The paper’s decision prompted GLF’s first action—a picket of the Voice—and the group’s first victory.[19]

Jerry Hoose, a member of the Aquarius Cell, talks about picketing the Village Voice

GLF and the New Left

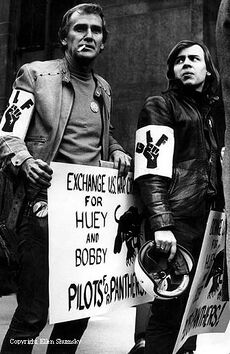

Many of the Gay Liberation Front's founders had been active in the New Left—the loose coalition of civil rights, black power, antiwar, student and feminist groups—and from the beginning, GLF aligned itself with a broader movement for social justice.

Ellen Shumsky was one such GLFer. After fighting for a number of New Left causes, she joined GLF in the fall of 1970.

GLFers believed that they could not find freedom in the current social and political system. As a result, they saw their participation in the Movement as essential to their own liberation. An early leaflet laid out the group’s radical analysis:

"GLF differs from other gay groups because we realize that homosexual oppression is part of all oppression. The current system denies us our basic humanity in much the same way as it is denied to blacks, women and other oppressed minorities, and the grounds are just as irrational. Therefore, our liberation is tied to the liberation of all peoples."[20]

GLFers threw themselves into New Left activism. They participated in actions against the Vietnam War, and for the Black Panther Party (BPP), the Young Lords Party (YLP), and women’s liberation, proudly holding the GLF banner even amidst harassment from other demonstrators.[21] The group also held dances and other events at Alternate University—a space in Greenwich Village used by a number of radical groups—to promote dialogue and exchange with the New Left. [22]

The Gay Liberation Front challenged the sexism and homophobia it saw in the New Left. GLFers believed that they were helping to bring about—as the slogan went—a “revolution in our time.” They wanted to ensure that this new society did not enforce the repressive gender and sexual norms of old. By participating openly in Movement activities, they could not only reach out to other radical gays and lesbians, but also gain acceptance from the New Left. As one GLFer argued, “only in getting our rightful place in the movement and demanding an end to our oppression can we ever really make changes for homosexuals.”[23]

Karla Jay talks about why she thought it was important to integrate GLF with the New Left

Not all members of the Gay Liberation Front agreed with the group’s alignment with the New Left. In fact, tensions about whether GLF should integrate with the Movement were present from the group’s second meeting—and continued throughout its existence.[24] In December of 1969, a number of GLFers left the group after it decided to donate $500 to the Black Panther Party. They formed the Gay Activists Alliance: a single-issue, reform-oriented organization that used a hierarchical structure and Robert’s Rules of Order. Their leaving caused the first of many splinters that tore at GLF.

GLFers Jerry Hoose, Karla Jay and Perry Brass share their views on the GAA split

As time wore on, even those who remained in GLF tired of the persistent homophobia they experienced from the New Left. Many straight male activists belittled gay liberationists or diminished their oppression as “trivial” compared to that facing poor or “Third World” people.[25] Epithets like “faggot” and “cocksucker” were commonly thrown at enemies like Reagan and Nixon, and slogans like “Up the Ass of the Ruling Class” peppered anti-war demonstrations.[26]

Even radicals like Martha Shelley began arguing that GLFers needed to focus on their own community before making alliances with other groups. "To become a revolutionary," she wrote, "...your own oppression must have first priority.”[27] And GLFer Step May spoke for more than just himself when he threatened Yippie leader Jerry Rubin: “Keep pushing me, Jerry, and you’ll find me allied with some ruling class pig who is also homosexual—allied against a common oppressor—the great freedom fighter Jerry Rubin.”[28]

Splinters and Dissolution

GLF brought together a wide range of people, and the group worked hard to accommodate the different needs, interests, and experiences of all of its members. Yet just as gays and lesbians had left New Left groups to come together around their own particular oppression, so too women, people of color, transvestites, and others eventually left GLF to organize groups—such as Radicalesbians, Third World Gay Revolution, and Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries—that centered on their identities and experiences. Their leaving was precipitated by persistent sexism, racism, class biases, and transphobia among some GLFers, but it also reflected a very real need to explore, understand, and fight back against their own oppression on their own terms.

The Gay Liberation Front collapsed within two years of its founding. The “structureless structure” that had energized participants in the group’s early days began to wear on many members as endless debates and discussions seemed to prevent action rather than facilitate it. Additionally, the group’s far-reaching goals prohibited it from achieving tangible results—leading many less radical men to leave the group for the reform-oriented Gay Activists Alliance.[29]

Martha Shelley remembered: “We got involved in these endless theoretical debates about what we should do and what our relationship was to other organizations. I think we just talked ourselves to death. And all these splinter groups formed…. GLF disintegrated into so many splinter groups that it just disappeared.”[30]

Even though GLF folded relatively quickly, the group gave birth to a new movement, one that was bold, assertive, and unabashed—and which continues to this day.

Perry Brass, Karla Jay, and Jerry Hoose talk about the dissolution of the Gay Liberation Front

Return to Gay Liberation in New York City

Categories

Gay Liberation, Stonewall, New York City, Gay Liberation Front, Gay Activists Alliance, Radicalesbians, Third World Gay Revolution, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, The New Left

Contact

Lindsay Branson: lindsay.branson@gmail.com

References

- ↑ Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Plume Books, 1993), 211-17; Toby Marotta, The Politics of Homosexuality (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 78-9; Donn Teal, The Gay Militants (New York: Stein and Day Publishers, 1971), 32-5.

- ↑ “What Is Gay Liberation Front?” Gay Liberation Front, Vertical File, Tamiment Institute Library, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University.

- ↑ “Gay Revolution Comes Out,” Rat, August 12-26, 1969, p. 7. Quoted in Marotta, Politics, 88; “Gay Oppression/A Radical Analysis,” (New York: Red Butterfly Publication), 5-6, Publications relating to Red Butterfly (Organization), Vertical File, Tamiment.

- ↑ John D’Emilio, foreward to Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation, 20th Anniversary Edition, eds. Karla Jay and Allen Young (New York: New York University Press, 1992), xxii-iii.

- ↑ The Red Butterfly Cell, “Freedom for Homosexuals – Homosexual Freedom for Everyone!” November 15, 1969, Gay Liberation Front (GLF) N.Y. Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives, Brooklyn, NY.

- ↑ Jim Foratt, "Word Thoughts," in Times Change Press Pamphlets (New York: Times Change Press, 1970), 16.

- ↑ D’Emilio, foreward to Out of the Closets, xxiii; Martha Shelley, "Gay is Good," Gay Flames Pamphlet, no. 1, Gay Liberation Front (GLF) N.Y. Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- ↑ D’Emilio, foreward to Out of the Closets, xxiii.

- ↑ Allen Young, “Out of the Closets, Into the Streets,” Out of the Closets, 29.

- ↑ Ibid., 8 and 30-1.

- ↑ Lois Hart, “GLF News,” Come Out! 1, no. 2 (January 10, 1970): 16.

- ↑ Jerry Hoose, “Gay Liberation Front—New York,” Gay Power 1, No. 13. (n.d.): 17.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 92.

- ↑ Hart, “GLF News,” 16.

- ↑ Terence Kissack, “Freaking Fag Revolutionaries: New York’s Gay Liberation Front, 1961-1971,” Radical History Review 62 (1995): 114.

- ↑ Teal, Gay Militants, 53; Bob Kohler, “Aquarius Cell,” Come Out! 1, no. 2 (January 10, 1970): 16

- ↑ For accounts of the atmosphere in gay bars, see: Martha Shelley, interview by Eric Marcus, Making Gay History (New York: Perennial, 2000), 134-5; Perry Brass, “Sisters and Brothers: A Writer Hungering for Family Finds GLF,” in Smash the Church, Smash the State, ed. Tommi Avicolli Mecca (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2009), 128; Karla Jay, Tales of a Lavender Menace (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 21-5.

- ↑ Quoted in Teal, Gay Militants, 58.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 112.

- ↑ “What Is Gay Liberation Front?” Emphasis in original.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 93; Teal, Gay Militants, 164.

- ↑ Allan Warshawsky and Ellen Bedoz, "G.L.F and the Movement," Come Out! 1, no. 2 (January 10, 1970): 5.

- ↑ Quoted in Kissack, “Freaking Fag Revolutionaries,” 108.

- ↑ Marotta, Politics, 82.

- ↑ Martha Shelley, “More Radical Than Thou,” Come Out! 1, no. 2 (January 10, 1970): 7.

- ↑ Kissack, “Freaking Fag Revolutionaries,” 111.

- ↑ Martha Shelley, “Gay Liberation Front – A Liberal Tea Party,” Gay Liberation Front (GLF) N.Y. Organizational File, Lesbian Herstory Archive.

- ↑ Step May, “An Open Letter to Jerry Rubin,” Gay Flames Pamphlet, no. 3, microfilm, 1 reel, New York Public Library.

- ↑ Kissack, “Freaking Fag Revolutionaries,” 128; Jay, Lavender Menace, 223 and 252-3.

- ↑ Shelley, Making Gay History, 189.