Difference between revisions of "AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989"

(New page: == '''AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989''' == The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities,...) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities, was transformed by the AIDS crisis. Though AIDS first came to national attention in 1981, in Atlanta, thanks in part to the presence of the Centers for Disease Control, gay activists began organizing around the issue as early as 1983. AID Atlanta, an all-volunteer educational and service organization, was among the first groups that formed. By the end of the decade, there existed a network of HIV/AIDS support and activism, including a local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and programs and organizations to address women and communities of color. | The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities, was transformed by the AIDS crisis. Though AIDS first came to national attention in 1981, in Atlanta, thanks in part to the presence of the Centers for Disease Control, gay activists began organizing around the issue as early as 1983. AID Atlanta, an all-volunteer educational and service organization, was among the first groups that formed. By the end of the decade, there existed a network of HIV/AIDS support and activism, including a local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and programs and organizations to address women and communities of color. | ||

| − | Much, though not all, activism during this decade centered on AIDS, and lesbians played an important role in the movement to educate people and to combat the increasingly vocal antigay forces from the Christian right and the Republican Party. All the while, evangelical ministers, among them Charles Stanley of the First Baptist Church of Atlanta, preached that HIV/AIDS was God's punishment for | + | <gallery> |

| + | |||

| + | Image:First Tuesday candidates rating_1980_AHC.jpg|Flyer, First Tuesday, 1980. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | Image:Atlanta Gay Center_Ponce_AHC.jpg|Photograph, Atlanta Gay Center, circa 1980. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | Image:AID Atlanta newsletter 1983_AHC.jpg|Newsletter, AID Atlanta, 1983. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | Image:Pulse_cover.jpg|First issue, ''PULSE'', 1984. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

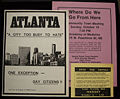

| + | Image:Atlanta Gay Guides_1986-1989_AARL.jpg|Guides, 1986-1989. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Much, though not all, activism during this decade centered on AIDS, and lesbians played an important role in the movement to educate people and to combat the increasingly vocal antigay forces from the Christian right and the Republican Party. All the while, evangelical ministers, among them Charles Stanley of the First Baptist Church of Atlanta, preached that HIV/AIDS was God's punishment for homosexuality. When Georgia native J. B. Stoner, a lifelong segregationist and white supremacist, led a mob confronting civil rights marchers in Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1987, he passed out leaflets that read "Praise God for AIDS" across the top. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <gallery> | ||

| + | Image:Evangelical Outreach Ministries_1985_AARL.jpg|Printed materials related to Evangelical Outreach Ministries, 1985. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | ||

| + | Image:Atlanta's Gay Ordinance_1986_AARL.jpg|Printed materials related to Atlanta's gay ordinance, 1986. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | ||

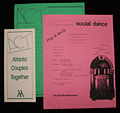

| + | Image:Atlanta Couples Together_1986_AARL.jpg|Printed materials related to Atlanta Couples Together, 1986. Courtesy of the Archives Division, Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History. | ||

| + | Image:TowerLounge_AHC.jpg|Photograph, Tower Lounge staff, circa 1988. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | Image:139.jpg|Photograph, Armorettes, circa 1983. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | Image:140.jpg|Advertisement, Weekends, 1984. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | Image:Atlanta River Expo_1988_AARL.jpg|Photograph, Atlanta River Expo participants, 1988. Courtesy of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

During the same period, another event of national import occurred, when in 1982, Atlantan Michael Hardwick was arrested in his bedroom for engaging in oral sex with another man. Hardwick appealed, aided by the ACLU and Georgians Opposed to Archaic Laws, but in 1986 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld Georgia’s sodomy statute. In response to the Hardwick case, a strong belief that the U.S. government was failing to adequately address the AIDS crisis, and ongoing discrimination, LGBT Atlantans responded vocally and visibly in local marches and rallies, as well as the second national March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987. | During the same period, another event of national import occurred, when in 1982, Atlantan Michael Hardwick was arrested in his bedroom for engaging in oral sex with another man. Hardwick appealed, aided by the ACLU and Georgians Opposed to Archaic Laws, but in 1986 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld Georgia’s sodomy statute. In response to the Hardwick case, a strong belief that the U.S. government was failing to adequately address the AIDS crisis, and ongoing discrimination, LGBT Atlantans responded vocally and visibly in local marches and rallies, as well as the second national March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Collective Power and Culture Wars - 1990 to 1999]] | [[Collective Power and Culture Wars - 1990 to 1999]] | ||

| − | [[Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History]] | + | [[Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History]] <comments /> |

Revision as of 18:39, 13 May 2010

AIDS and Politics - 1980 to 1989

The popularity of bars and parties did not wane in the 1980s, but the gay and social political landscape of Atlanta, as in other major cities, was transformed by the AIDS crisis. Though AIDS first came to national attention in 1981, in Atlanta, thanks in part to the presence of the Centers for Disease Control, gay activists began organizing around the issue as early as 1983. AID Atlanta, an all-volunteer educational and service organization, was among the first groups that formed. By the end of the decade, there existed a network of HIV/AIDS support and activism, including a local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and programs and organizations to address women and communities of color.

Much, though not all, activism during this decade centered on AIDS, and lesbians played an important role in the movement to educate people and to combat the increasingly vocal antigay forces from the Christian right and the Republican Party. All the while, evangelical ministers, among them Charles Stanley of the First Baptist Church of Atlanta, preached that HIV/AIDS was God's punishment for homosexuality. When Georgia native J. B. Stoner, a lifelong segregationist and white supremacist, led a mob confronting civil rights marchers in Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1987, he passed out leaflets that read "Praise God for AIDS" across the top.

During the same period, another event of national import occurred, when in 1982, Atlantan Michael Hardwick was arrested in his bedroom for engaging in oral sex with another man. Hardwick appealed, aided by the ACLU and Georgians Opposed to Archaic Laws, but in 1986 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld Georgia’s sodomy statute. In response to the Hardwick case, a strong belief that the U.S. government was failing to adequately address the AIDS crisis, and ongoing discrimination, LGBT Atlantans responded vocally and visibly in local marches and rallies, as well as the second national March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987.

Collective Power and Culture Wars - 1990 to 1999

Atlanta Since Stonewall, 1969-2009: A Local History <comments />