Weena Perry: NYC Museums’, Part 2

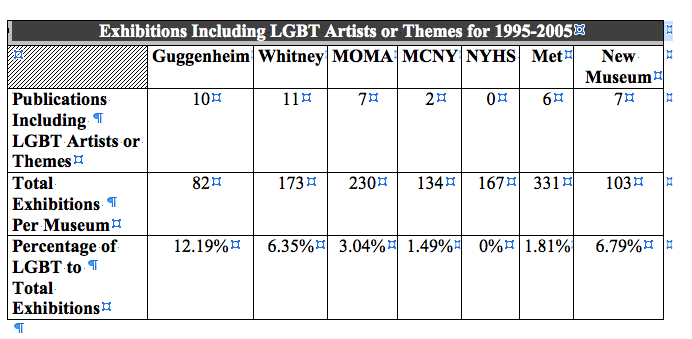

Number and Percentage of Exhibitions Including LGBT Artists or Themes

Analysis of a decade of exhibitions reveals a marked degree of under-representation of LGBT issues in the work showcased by New York’s major museums. Less than 2% of the Met’s exhibitions reference LGBT artists or themes. Even museums celebrated for cultural diversity, such as the New Museum, included only 6.79% of LGBT artists or themes over the study period. The New York Historical Society, which purports to celebrate the city’s history, has never had a show marking the contribution of New York’s extensive LGBT community to the city’s history. Given that sexual diversity became increasingly evident throughout the 20th century, it is surprising that even the Museum of Modern Art, with 3.04%, fails to mirror this great cultural shift.

Of all the museums under study, the Guggenheim devoted the most attention to LGBT artists or themes (12.19%). The New Museum (6.79%) and the Whitney (6.35%) came in a distant second and third place. The Guggenheim also produced fewer exhibitions for the period under study, 82 compared to the Whitney’s 173 and to the New Museum’s 103 exhibitions. Thus the sheer volume of exhibitions generated by larger museums should be taken into consideration when evaluating the data. On the other hand, even given the gargantuan nature of an institution such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the extremely low figure of 1.81% of LGBT artists or themes represented over the ten-year study period is a troubling statistic, especially for a museum with significant holdings in art of the modern era. Moreover, given the extensive scholarship on homoeroticism in pre-19th century Asian art one cannot accept the argument that only Western art contains LGBT themes.[1]

Perhaps the most disturbing figure is the complete absence of LGBT artists or themes from the New York Historical Society’s exhibition record for the period under study. Given that the NYHS purports to document and communicate New York history, the refusal to listen to LGBT voices and to see the contribution of the LGBT community to New York is of utmost concern. The Museum of the City of New York, with 1.49% of LGBT artists or themes, or 2 out of 134 exhibitions, barely fared better than the NYHS.

On Mission Statements, Governance, and Funding

What obligation do these institutions have to either display or discuss LGBT produced or themed art? The suppression or obfuscation of the historical record being presented to an unwitting public contradicts the common understanding of museums as ideologically neutral or even socially progressive. If art historical accuracy or moral responsibility are not sufficient reasons, then perhaps an examination of the museums’ mission and finance related statements will provide further insight into this question of obligation.

The City of New York helps fund the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a “not-for-profit institution”: “For more than a century, the City of New York and the trustees of The Metropolitan Museum of Art have been partners in bringing the Museum's services to the public. The complex of buildings in Central Park is the property of the City, and the City provides for the Museum's heat, light, and power. The City also pays for about half the cost of maintenance and security for the facility and its collections.”[2]

Space added.

The finance section on the Met’s website credits the City with 15% of its support.[3]

Space added.

The New York Historical Society’s website notes that “[p]ublic programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.”[4] The Museum of the City of New York’s website credits some of its support to the City as well: “[The MCNY] is supported in part by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and by the New York City Council, the Honorable Christine C. Quinn, Speaker.”[5] The MCNY claims that, “The Museum of the City of New York embraces the past, present, and future of New York City and celebrates the city’s cultural diversity.”[6] How does the ongoing exclusion of the LGBT community “celebrate” New York’s famed diversity? The NYHS states that, “[t]he Society is dedicated to presenting exhibitions and public programs, and fostering research that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, its holdings cover four centuries of American history, and include one of the world’s greatest collections of historical artifacts, American art and other materials documenting the history of the United States as seen through the prism of New York City and State.”[7] Yet for the last ten years New York’s LGBT history has been completely absent from its exhibition record.

While New York’s political administrations have increasingly courted the LGBT population, the city’s cultural institutions supported by municipal funds continue to discriminate against the community. Mayors and other administration officials march in the annual Gay Pride Parade—the largest of its kind in the nation. Yet the city’s public cultural institutions, which exist to represent the rich diversity of the city, continue to actively repress information about one of its most socially, culturally, economically, and politically active communities. Museums that receive funding from public sources should be accountable for exclusionary or discriminatory practices.

What about the private institutions? Perhaps these institutions have no legal obligation to the public because they are not bound by public policy, yet comparing their mission statements with practice yields questions. The Whitney Museum of American Art claims:

- Despite its early emphasis on realist art, the Whitney Museum has long been dedicated to assembling a collection that offers a comprehensive picture of twentieth-century American art. Although the collection is characterized by its breadth, it is equally recognized for its in-depth commitment to the work of a number of artists. In addition to the Hopper and Marsh collections, the Whitney has the largest body of work by Alexander Calder in any museum, ranging from the ever-popular Calder's Circus and Surrealist-inspired pieces of the 1940s to large-scale mobiles and stabiles. Other in-depth concentrations include major holdings by Marsden Hartley, Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles Burchfield, Gaston Lachaise, Louise Nevelson, and Agnes Martin.

Almost half the artists acknowledged in the mission statement are the subject of extensive LGBT studies scholarship, yet only rarely has the Whitney foregrounded the LGBT issues openly discussed in the scholarly record. If the artists merit prominent inclusion in the website mission statement, then the museum should deal forthrightly with the work. How is excluding the LGBT issues or biography of the artists evidence of the Whitney’s “in-depth commitment”?[8]

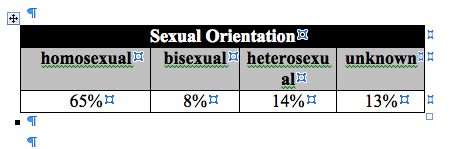

Sexual Orientation of the Artists in the Study

A significant majority of the artists included in the study were “homosexual”, meaning women and men either self-identified as lesbian or gay, or are discussed as such in the public record of LGBT encyclopedias, historical or art critical publications, or news articles. By “discussed as such,” I include artists such as Berenice Abbott, who were fairly public about their lovers or partners in their youth, yet repudiated being gay later in life.[9] Eight percent of artists in the study claimed identification or have been identified as bi-sexual, while 14% artists were heterosexual. The “unknown” category came in at 13%. This percentage is mostly comprised of younger artists included in group exhibitions who have not achieved a significant public biographical record, yet whose work explores LGBT issues.

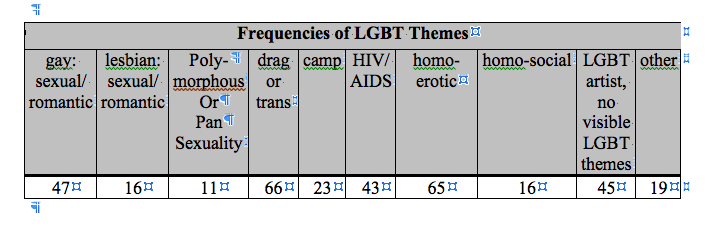

Recurring LGBT Themes in the Work

In order to ascertain the modes of public representation of LGBT artists or LGBT themed work, the study divided the exhibited works into the following thematic categories: • gay or lesbian sexual/romantic • polymorphously or pan sexual (to account for imaginative works that transcend dualistic biological or conceptual categories) • HIV/AIDS • drag or transgender • camp • homoerotic • homosocial (in acknowledgement of the body of scholarship on art representing emotional or social, but not necessarily erotic, connections between people of same the gender) • known LGBT artists whose work has no visible LGBT themes • “other” (to allow for works that elude the above categories)

While it is difficult to affix neat labels to the wide range of complex social and political issues present in cultural production, it was necessary to assign specific categories to recurring themes in the works. After all, any community that feels under- or misrepresented in the common culture needs to demonstrate that there exist common themes, social prejudices, stereotypes or shared issues that museums must acknowledge and discuss.[10] The presence of “LGBT themes” is separate from the issue of whether or not the museums chose to interpret, de-emphasize, or simply ignore the LGBT aspects of the works of art in their exhibitions.

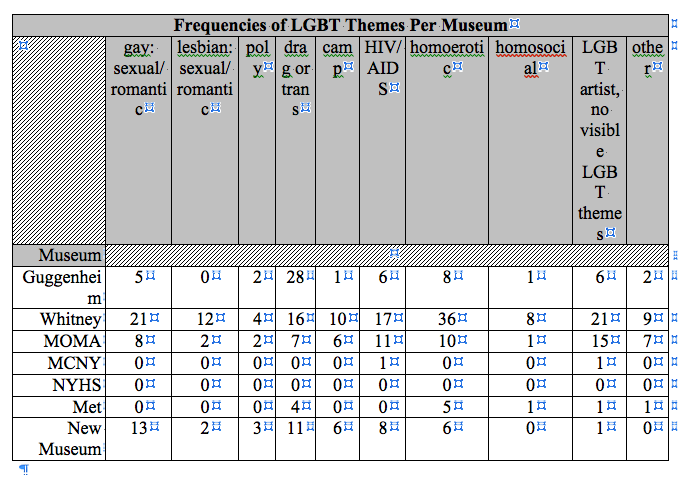

Before explicating findings, a few more details regarding the methodology for this section is necessary. When gathering data for each museum in the study, each exhibition was assigned a form on which the exhibited LGBT artists (or heterosexual artists showing LGBT themed works) were noted individually by name. (This separation was especially crucial when managing data for group exhibitions.) After examining the listed or pictured works for each artist, each applicable theme was checked off. The “yes” frequencies apply to the artist; not to individual works of art. For example, the Nan Goldin exhibition, I’ll be your Mirror (1996) at the Whitney, received one “yes” per each of the following LGBT thematic categories: gay: sexual/romantic, lesbian: sexual/romantic; drag or trans; HIV/AIDS; homoerotic; and homosocial. However, as an institution, the Whitney received 21 “yeses” for gay: sexual/romantic, meaning that 21 artists (or artists’ collectives working under a single name) exhibited work that dealt with sexual or romantic subject matter between men.[11]

However, when all the museums of the study were tabulated, there were 47 “yes” frequencies for the theme, “gay: sexual/romantic”. Certain works by certain artists overlapped thematic categories, thus making it necessary to use frequencies rather than percentages when presenting the data.

The “sexual/romantic” heading recognizes the diversity of art that aims to communicate the complex emotional and sexual practices of LGBT people. Like many humans, LGBT people tend to distinguish between romantic attachment and sexual gratification. This distinction is reflected in the art. Hence, this category includes portraits of artists’ lovers or partners, such as Tchelitchew’s pen and ink portrait of his lover, Charles Henri Ford (1937) included in MOMA’s Modern Art Despite Modernism (2000). Or, consider for example, Robert Mapplethorpe’s more exuberantly raunchy photography (Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition: Photographs and Mannerist Prints at the Guggenheim, 2004).

The “sexual/romantic” category was then subdivided between “gay” (male) and “lesbian” (female) because it became quickly apparent that lesbians were being underrepresented in the exhibitions. Gay romantic or sexual subject matter occurred in 47 times, while lesbian romantic or sexual subject matter was represented by only 16 artists. Note that the Whitney showed 12 of these 16 artists who explored lesbian sexual/romantic themes. This disproportionate figure emphasizes the dismal contributions of the remaining museums: in short, except for the Whitney, there has been a long-standing—indeed flagrant—disregard of lesbian themed work. As various minorities rights groups and feminists have repeatedly observed, there exist hierarchies among the discriminated. Women have not achieved parity in the art world at large, so it is hardly surprising to discover that lesbians fall far short of the recognition that gay male artists have managed to secure.[12]

“Polymorphous or Pan Sexuality” occurred in the work of 11 artists. “Polymorphous or Pan Sexuality”, an admittedly awkward construction that splits the difference between Freudian and Neo-Pagan terminology, attempts to account for work that delves into sexual terrain yet utterly refuses to be confined to conventional sexual or love objects. For example, Francesco Clemente has produced a number of delightfully imaginative and even fantastical works that confound normative sexual categories. Clemente, a heterosexual artist, has not only produced work that evokes LGBT themes, but also had a history of interacting or collaborating with some of the most famous LGBT artists of the 20th century, including Allen Ginsberg and Andy Warhol.[13] Interestingly, another heterosexual artist, Mathew Barney, is notable for his ripe imagination, having created a number of provocative human-animal hybrids for his Creamaster Cycle.

“Drag or trans”, like the theme of polymorphous or pan sexuality, defies discrete or normative identity categories. Specifically “drag or trans” concerns works of art that enact or represent a refusal to occupy the single gender category most humans are assigned to at birth.

With a frequency of 66, “drag or trans” work takes up the largest piece of the LGBT thematic pie, even outstripping homoeroticism. Given the broadness of the cultural concept of “homoeroticism,” the fascinating possibilities of which supply the fodder for endless jokes in popular culture, how do we account for the stronger presence of the edgier “drag or trans” thematic? Logistically, this figure is strongly skewed toward a single exhibition, the Guggenheim’s Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance and Photography, an exemplary show curated by Jennifer Blessing in 1997 whose catalog included noted LGBT scholars such as Judith Halberstam. With 28 artists working in this thematic area, Rrose represents a significant percentage of the total (The Whitney, with 16 artists dealing with this theme came in a distant second.) However, one also needs to consider the broader historical context of the appearance of “drag or trans” themed art in the art world. Beginning in the mid-1990s it became fashionable to engage in gender-bending or gender critical work in the art world.[14] Notably, heterosexual artists, such as Mathew Barney, who engage in drag or trans practice for their work, receive more large-scale curatorial attention than any of the LGBT artists in the study (for example, Catherine Opie).[15] In short, before we uncritically celebrate the fluidity of gender, and castigate retrograde categorization, perhaps we should consider the ways in which non-normative practices and identities can all too often be co-opted by the mainstream to inject a little frisson of exoticism into the status quo.

Degree of interpretation or presentation of LGBT themes in exhibition catalog and online materials

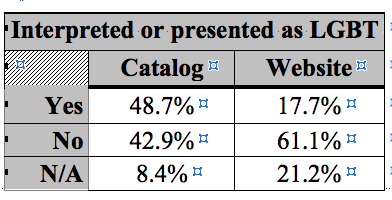

With regard to communicating LGBT themes in the work, there is a stark difference between what catalog essays are willing to say versus the didactic materials on exhibition web pages. While 48.7% of LGBT produced or themed works included in the study were presented as LGBT within the pages of exhibition catalogs, only 17.7% were presented as such within the museum web pages for the exhibitions.

This discrepancy causes grave concern because didactic materials on the websites are more likely to reflect the content of the original wall text that appeared in the exhibition. While hard data for wall text was unavailable for this phase of the study, interviews with LGBT art professionals indicate that museums significantly downplay the LGBT content or meaning of the art on display in their institutional spaces. In short, exhibition viewers are much more likely to learn about LGBT themes in exhibited works if they choose to read catalog essays, an act that involves a significantly greater time commitment and monetary expense than either viewing the exhibition in situ or on the museum’s website. Failing to educate the public about the LGBT subject matter or significance of the work, or of the work’s producer, does a profound disservice to the work as a cultural document, to the LGBT community which has produced a number of greatly respected and admired artists, and to the society as a whole. Historically, museums have represented themselves as civic institutions that not only educate societies, but also bridge divisions between diverse social groups by allowing everyone to celebrate and participate in a common culture.[16] Excluding or downplaying LGBT artists or their work violates this historic mission. Honestly communicating and presenting LGBT themes in art and an artist’s LGBT identity is thus a pressing civic and moral issue as well as one of art historical accuracy.

Degree of Interpretation or Presentation of LGBT Themes in Catalog Essays, By Museum

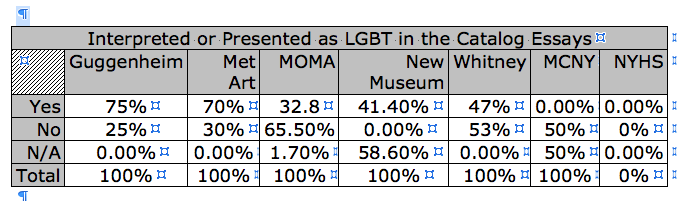

“Interpreted or Presented as LGBT in the Catalog Essays” demonstrates to what degree individual museums in the study addressed LGBT issues in their catalog essays. The “N/A” designation pertains to the percentage of unavailable catalogs, yet the exhibitions in question were included in the study because the museum posted significant information about the exhibition on its web pages. The one exception is an exhibition titled Gay Men’s Health Crisis (2001) curated at the Museum of the City of New York. While no information about the exhibition was available either in the form of a catalog or a web page, the title of the exhibition was self-evidently LGBT, so it was included in the study. Given that the Museum of the City of New York had only two LGBT artists or themed exhibitions in the study, it was especially crucial to make note of Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

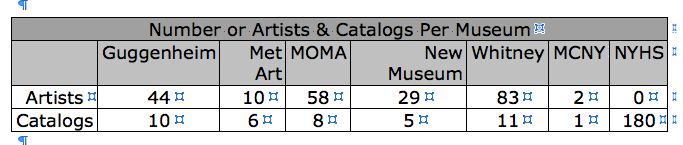

With75% in the affirmative, the Guggenheim’s catalog essays addressed LGBT issues at a higher percentage than the other museums in the study, but with 70% the Met reached a close second. However, there are other factors that need to be taken into consideration when evaluating these figures. “Count Per Museum” shows both the number of artists included in the study per museum and the number of catalogs. The Guggenheim had 44 artists in 10 catalogs, while Met had 10 artists in 6 catalogs. Moreover, 5 of the Met’s 10 eligible artists were discussed in the catalog for the exhibition, Surrealism: Desire Unbound (2002). This exhibition and the catalog originated from the Tate Gallery in London; therefore the acknowledgment of LGBT issues is the Tate’s doing, not the Met’s. The Met’s catalog essays failed to address the LGBT issues for exhibitions on Leonardo da Vinci and Christian Dior. The Thomas Eakins catalog originated from the Philadelphia Museums of art. As noted in the introduction for this report, art historian Jonathan Katz attempted several times to interest the Met in making room for a public panel that would address the body of LGBT scholarship on Eakins, but the Met refused.[17] Therefore, even though the catalog was not its creation, the Met declined opportunities to address LGBT issues related to Eakins. The Met’s catalog for Diane Arbus mentioned her photography of transvestites and LGBT people. The Met’s catalog for a Gianni Versace retrospective in 1997 was frank about the late fashion designer’s gay identity and how it impacted his work. In sum, only one of the catalogs originating from the Met significantly acknowledged the LGBT aspects of the artist or work being presented.

All other exhibitions under consideration originated with the museums being studied, thus making the percentage of catalog essays discussing LGBT issues a more accurate reflection of the museum’s/curator’s attitude toward LGBT issues than what the figures from the Met indicate. For the Whitney, 47% of the essays acknowledge LGBT issues. The New Museum follows at 41.4%. MOMA came in at 32.8%. Because the catalog for MCNY’s Gay Men’s Health Crisis was unavailable, it has a “yes” percentage of 0. (The catalog for the MCNY exhibition on Berenice Abbott, Changing New York (1997) did not acknowledge the LGBT aspects of Abbott’s biography or photography.) The New York Historical Society has a resounding 0% because none of its shows included LGBT figures or themes.

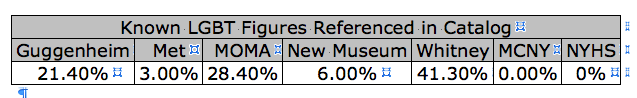

Catalog Referencing of Known LGBT Figures or LGBT Artists’ Lovers or Partners

In addition to considering the degree of inclusion of LGBT artists or themed works, it is also useful to examine other aspects of LGBT representation in museum catalog essays, including discussion of the romantic relationships of the LGBT artists included in exhibitions, and any references to other LGBT artists or historical figures (whether these figures were a part of the artists social or professional networks). The Whitney exhibition catalogs for the period under study included a significant majority of references to known LGBT figures. With 41.3%, the Whitney easily outstripped the MOMA’s 28.4% and the Guggenheim’s 21.4%. Only 3% of the Met’s catalog’s included references to known LGBT figures, while the MCNY and NYHS had no references. As noted earlier, for the MCNY no catalog was available for one of its two LGBT eligible exhibitions.[18]

These figures demonstrate that even when these institutions do not discuss the LGBT themes of the work being exhibited, there exists a potentially rich LGBT context of social and professional associations behind the works and the works’ producers. These figures also tend to correspond to the overall willingness to the catalog essays to engage with LGBT themes in the work: see “Interpreted or Presented as LGBT in the Catalog Essays”. (Note that the Met is the primary exception because of the statistical distortion explained above.)

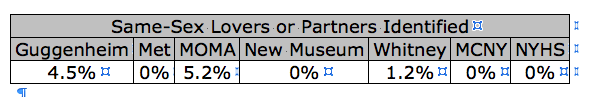

When comparing “Known LGBT Figures Referenced in Catalog” with “Same-Sex Lovers or Partners Identified”, one sees a vast difference between museums’ willingness to reference known LGBT figures (given the historical prominence of many of these figures, it is hard to avoid) and the willingness to discuss the personal romantic attachments of LGBT artists. The figures drop off radically. MOMA’s catalogs led with the low figure of 5.2%. Only 4.5% of Guggenheim’s catalogs acknowledged lovers or partners, while a mere 1.2% of the Whitney’s did. None of the other museums’ catalogs discussed the romantic attachments of their LGBT artists at all.

Examples of the Downplay or Suppression of LGBT identities or themes

The above examination of why the Met yielded a high “yes” percentage for LGBT interpretation even though the museum has consistently ignored LGBT artists or themes over the years, underscores an extremely important problem with regard to relying solely on statistics to illustrate the museums’ varied approaches to LGBT issues. Statistics simply do not tell the whole story. For example, they cannot convey the nuances of interpretation in catalog essays. The above figures certainly cannot demonstrate how the degree of LGBT interpretation is contingent upon the curator or on the theme of the show. For example, a show such as the Guggenheim’s Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography, curated by Jennifer Blessing in 1997, is rich with LGBT themes and artists. Its catalog included essays by well-known LGBT scholars and artists, such as Judith Halberstam and Lyle Ashton Harris. It is therefore crucial to consider in greater detail the ways in which museums downplay or suppress the LGBT identities or aspects of the work being exhibited. This section will first provide individual examples, followed by comparisons between how different museums approached the same artists or material, and then finish with cross-comparisons within museums that demonstrate how different exhibitions/curators/catalog contributors approach the same artists or themes.

Individual Examples

The Guggenheim:

Ellsworth Kelly: A Retrospective

October 15, 1996–January 15, 1997

The catalog essays for Ellsworth Kelly: A Retrospective consistently employ language of the closet by treating Kelly’s sexual identity as the proverbial elephant in the room. Kelly, and the other LGBT members of his milieu, function as an unacknowledged LGBT half of a homosexual/heterosexual binary in the machismo-permeated atmosphere of postwar New York’s Abstract Expressionist realm. Robert Indiana, “Agnes Martin & Lenore Tawney”, James Rosenquist, “Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg”, along with Kelly, are presented as artists who moved to Lower Manhattan to get away from the Ab Ex artists of Greenwich Village “with whom they had little in common (27).” Could the absence of commonality have something to do with the fact that everyone mentioned but Rosenquist was not heterosexual, and that a number of the Cedar Tavern group were overtly hostile to gays? Moreover, the essay actually groups romantic couples in pairs— “Agnes Martin & Lenore Tawney” and “Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg”—without acknowledging the nature of the relationships within these pairs.[19]

The entry for Robert Indiana in the online encyclopedia, glbtq: an encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and queer culture identifies Kelly as Indiana’s lover during this period, when the above artists were living on the old industrial Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan.[20] Of Kelly’s and Indiana’s romantic involvement we learn nothing.[21] Yet we do learn that Kelly’s “good friend” Jack Younger, a fellow American studying in Paris under the G.I. Bill, married the “French actress Delphine Seyrig” in 1950 (14). Why inform of us of the heterosexual coupling of Kelly’s associates, information that does nothing to advance our understanding of Kelly’s art practice, whereas awareness of Kelly’s homosexuality certainly would?

Another essay argues that Kelly’s transcendent impulses actually identify him with Abstract Expressionism more than the minimalism of the 1960s (64). “However, Kelly’s voluptuous and at once impersonal style is at odds with the high degree of individual expressiveness of the New Yorkers.” Why was Kelly’s style so “impersonal”? The catalog describes Kelly as sharing an “anti-illusionist” position with Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg while also noting that the three artists “developed in different directions (41).” Yet no note is taken of the shared sexual orientation of these artists, and how it might affect their perspective on the issue of personal expression in art by gay men in the dangerous anti-gay climate of this period in American history. Why are they so different in practice but similar in attitude?

Instead we are given to know that unlike the “action” paintings of the Ab Ex artists, “Kelly’s view of painting was more introspective and contemplative (11).” This choice of adjectives without social grounding is oddly evocative of both pop- and professional psychology and sociology of the 1950s, which invoked a host of euphemisms to single out the non-normative male and helped feed the homosexual panic of the period. How could an exhibition catalog in 1996, put out by a museum that had recently explored the LGBT issues in of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Ross Bleckner, engage in such retrograde euphemisms, misdirection, and suppression? Do we simply ascribe it to the closeted status of the artists, or is this gay effacement part of the larger culture of museums?

As with Jasper Johns art, Kelly’s work is regularly described in museum catalog essays as having sensuous or erotic qualities, although the human connection behind these impulses remains a specter. In this particular catalog, several of the essays make note of the erotic and sensual only to cast these qualities adrift by divorcing them from Kelly’s actual lived experience. A weird vacuum is created for anecdotes such as Kelly arranging his red paintings in a circle in his Coenties Slip studio & then dancing naked among them. Something is missing from the claim that “a virtually pagan component to his spiritual fervor” can be seen in Kelly’s practice. Something is missing too from the caption of the photograph of Kelly, nude, holding one of his paintings, “Kelly at Coenties Slip studio,” New York, 1958” (Fig 2, p.63). Who took this photograph? Who sees Kelly naked like this?

The Guggenheim:

Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective

September 19, 1997 – January 7, 1998

Oddly, while there is a concerted effort to link Rauschenberg to the founding fathers—both Benjamin Franklin & Thomas Jefferson are invoked—the Guggenheim’s catalog for Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective overwhelmingly suppresses the personal realm. The Guggenheim eliminates all references to romantic relationships, even mentioning Rauschenberg’s ex-wife Susan Weil only in a professional context (further commentary on museums’ treatment of Rauschenberg’s marriage follows in the next section). We learn of Rauschenberg’s “…move to Pearl Street …in September 1955, one floor above his close associate Jasper Johns.” We learn that “[a]lso critical to Rauschenberg has been his relationship with friends and collaborators Cage and Merce Cunningham (23).” Cage and Cunningham were domestic as well as professional partners, but we do not learn of this connection. The rich possibilities of exploring the issue of closeted gay men creating a vibrant artistic community whose art has had lasting impact on contemporary culture remained an untapped source in an exhibition purporting to be a “retrospective”.[22] The issue of Rauschenberg’s sexuality and its impact on his life and work was so stifled in the catalog that it’s not even possible to read into the text as one can with the Kelly retrospective of the previous year.

Comparisons between Museums’ Treatment of LGBT Artists or Themes

1) Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns: the Guggenheim, the Whitney, and MOMA

Despite the growing body of LGBT scholarship and encyclopedia entries on Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, both as a couple who were romantically and professionally involved during the 1950s, and individually as gay male artists, a wall of silence has been built by museums between the artists and the public.[23] In the future, perhaps the reasons for this refusal to engage with the sexuality of the artists and its place in their work will be ascertained. Is it self-censorship on the part of museums? Is it because the artists, who are still living at the writing of this report, will only cooperate with institutions and professionals who shore up the wall of silence? Although the artists’ sexual identities long ago entered into the public record of art historical discourse, and indeed both Johns and Rauschenberg were featured among the 100 most famous gays and lesbians by New York magazine, public discussion of such matters has resulted in the censure of certain LGBT scholars who dared to put the issue front and center in their research. [24]

Guggenheim

The Guggenheim’s retrospective on Rauschenberg ruthlessly wiped out all romantic references, even going so far to refer to Rauschenberg’s ex-wife Susan Weil only in her professional capacity as a collaborator with the artist. One almost has to admire the logic of “if there will no homosexual romantic references, then there will be no heterosexual references either.” An earlier group exhibition does manage to acknowledge that the two men knew each other: Abstraction in the Twentieth Century: Total Risk, Freedom, Discipline February 8–May 12, 1996 describes Jasper Johns as an “early friend of Rauschenberg (160).” Given the utter blandness of the term “friend”, the bracing nouns of the title—risk, freedom, discipline—droop with weary irony.[25]

The Whitney

When compared with the Guggenheim, the Whitney’s euphemisms about the pair border on the impertinent. Part two of The Whitney’s American Century exhibition discusses Rauschenberg and Johns while avoiding defining the nature of their relationship. “From 1956 to 1961, the two shared loft space in lower Manhattan. During this period, they nourished and encouraged each other in many ways, producing exceptional bodies of work, opening up territory that would be mined by artists for decades (89).” The essay does acknowledge Rauschenberg’s marriage to Susan Weil (92). But the reader is left to wonder in which “ways” did this nourishment and encouragement occur. Yet none other than Rauschenberg himself stated in a published 1990 interview, “It was sort of new to the art world that the two most well-known, up and coming studs were affectionately involved.[26]

MOMA

One has to hunt through the MOMA’s catalog, Jasper Johns: A Retrospective, October 20,1996–January 21, 1997, in order to find reference to Rauschenberg. When finally reaching the chronology at the end, one sees that Rauschenberg permeates the 1950s section – but the nature of his relationship to Johns remains unacknowledged. This section even includes the famous quote from John Cage who once said of the pair, that “each seemed to pick up where the other left off (125).” It is absolutely crucial to underscore that only readers educated in the game of “pick out the gay subtext” will grasp that Cage is referring to something deeper and more emotionally intense than artistic collaboration.

What I find striking about the perpetuation of 1950s style homophobia in contemporary exhibitions is how this type of bias, this fearful or timid handling of sexuality, actually runs counter to the ways in which museums now handle other historic episodes of bias or violence, ranging from the murder and abuse of Native Americans during the expansion of the American frontier, to the genocide of millions of Jews during the Holocaust of World War II, and to the history of first the enslavement and then the civil rights violations of African Americans. On a nonviolent level of bias, consider that since the early 1970s there have been exhibitions devoted to women’s art and issues. Why is it still permissible to exclude LGBT issues from discussion when they permeate the collections of the most respected museums of the world?

2) A comparison of certain artists in group exhibitions:

The Whitney Museum of American Art

The American Century, Part One 1900-1950

April 25 – September 20, 1999

MOMA

Making Choices (catalog is titled Modern Art Despite Modernism)

March 16 – September 26, 2000

A comparison between how the Whitney and MOMA approach the representation of LGBT artists and art produced before the 1950s reveals great differences. As noted in the section below comparing exhibitions produced by the same institution, curator Barbara Haskell’s catalog for part one of The American Century (1999) employed closeting language in discussing the gay subject matter of Marsden Hartley, and also failed to put a name to the homophobia of the art world even while discussing the effects of this homophobia on gay artists. Haskell’s treatment of Paul Cadmus’ homoerotic works evaded the frankly gay nature of his art practice, remarking only that the secretary of the navy “lodged” a complaint against the Fleet’s In! “for its licentious portrayal of sailors (421).”[27]

In comparison, MOMA’s Robert Storr approached the artists and works of the same period with a degree of openness completely absent from The American Century catalog. These differences are all the more striking because the exhibitions appeared only a few months apart from one another. Of the same period discussed by Haskell, Storr writes:

- In their work an unmistakable homoeroticism appears to a degree in American art of this period outside of Demuth’s watercolors, the drawings and paintings of Hartley, and the poetry of Hart Crane, who was also a member of Kirstein’s circle. Thus Cadmus’s riotous Greenwich Village Cafeteria [p.183] introduces into the Social Realism of the day the come-hither glance of the man heading into the bathroom. …Tooker’s paintings are dreamier and more discreet…The example set by these artists, augmented by that of Tchelitchew, Cocteau, and a host of others, is a reminder that in times when intolerance of homosexuality ran high even among ‘progressives,’ the avant-garde was in many instances a haven for gay painters, sculptors, and photographers—make and female—and a context in which a variety of more or less explicitly gay sensibility could be explored (70).

What the passage by Storr reveals is that art does not have to have originated in 1980s or 1990s, or to be about HIV/AIDS, in order for a museum to deal frankly and honestly with the LGBT aspects of the works in its collection or on view. While the section comparing shows within the same institution discusses examples of MOMA’s shortcomings as an institution, Robert Storr, as a curator and essayist, serves as a fine example of what museums today should be doing when presenting LGBT artists and works to the public. Whether discussing contemporary or Pre War artists, Storr is clear in pinpointing and drawing out LGBT issues in a manner that is neither evasive nor patronizing toward any presumed delicate sensibilities of the “average” heterosexual viewer.

Comparisons within Museums of LGBT Artists or Themes

The Whitney Museum of American Art

The American Century, Part One 1900-1950; Part Two 1950-2000

1999

The American Century was a two part exhibition: part one, 1900-1950 was curated by Barbara Haskell, while part two, 1950-2000 was curated by Lisa Phillips. For each catalog, the curators and catalog contributors radically diverged in their treatment of LGBT issues, thus begging a comparison. The index for the catalog for part one contains no LGBT references whatsoever, whereas part two makes room in its index for “gay rights,” “AIDS,” and “homosexuality.”

Besides the fact that “homosexuality” existed in the art world (and the world at large) before 1950, the reader should not be fooled by the indexical oversight of the catalog for part one. The American Century, 1900-1950 does include LGBT artists and themed work. Charles Demuth, Paul Cadmus, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Pavel Tchelitchew were all represented. Some of the work evidenced no visible LGBT themes, but other works were of a homoerotic or gay romantic nature; while still others represented subjects who were in drag or who were transgendered.

LGBT biographical information would have helped in understanding certain of the works. However, closeting language obfuscated the poignant intensity of Marsden Hartley’s elegiac abstractions about his deceased lover, a German officer who died in combat during WWI. The catalog essay referred, twice, to Hartley’s lover as his “friend”, an appellation familiar to many in the LGBT community who have tolerated euphemistic introductions made by squirming family members in social situations. These kinds of euphemisms have a jarring presence in professional art publications of today.

What is especially disconcerting about the gay veiling of Hartley’s work is that elsewhere in the catalog is a discussion of Stieglitz’ milieu, where we discover that despite Hartley’s “homosexuality,” his work had a “virile” quality and was thus respected by the Stieglitz circle who rejected Charles Demuth’s “delicate niceness (203).” The homophobia of the Stieglitz circle is not remarked upon. Moreover, it is most puzzling as to why the subject of Hartley’s sexual identity had to be avoided when actually discussing the very work where this absence was most striking. In an age where Oprah Winfrey’s LGBT guests have brought heterosexual audience members to tears with their stories of suffering at the hands of bigots, of lives left unrealized because of the closet, and of lives lost because of AIDS, the Whitney Museum of American Art and certain of its curators would seem to underestimate the people who flock to its exhibitions, curious about the art and artists under study.

In comparison, The American Century, 1950-2000 comes off as a celebration of LGBT presence in the art world. LGBT issues actually make the index. “Homophobia” is discussed as part of the 1950s culture of anxiety and xenophobia (37). Beat poetry is singled out for its “openly gay lyrics (61).” The catalog falters by displacing Andy Warhol’s gayness onto his “entourage” while reserving the term “asexual” to describe him (130).[28] It regains its footing with an extensive discussion of AIDS and the Culture Wars of the 1980s. However, unless a gay artist is addressing AIDS or is in drag, then the artist’s sexual identity or LGBT issues of the work do not rate exploration. In some cases, works dealing with LGBT themes are included but not discussed as such, including Larry Rivers portrait of his then lover Frank O’Hara, Jess’ deconstruction of macho comics, and Catherine Opie’s self-portrait of a stick figural lesbian domestic scene scratched into her back. Despite the Whitney’s overall inclusion of lesbian produced or themed art for the period under study, the lesbian presence barely registers in the catalog essays for The American Century. In the catalog, lesbian or feminine homoerotic issues in 1970s work were masked by the assumed heterosexuality of “Feminism” in art, although LGBT scholarship has taken note of the homoerotic aspects of presumably heterosexual works such as Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party.[29]

MOMA

On the Edge: Contemporary Art from the Werner and Elaine Danheisser Collection Sept 30, 1997 – Jan. 20, 1998.

Tempo

June 29 – September 9, 2002.

When comparing exhibitions within MOMA, there are striking differences in how curators or catalog essay contributors handle LGBT artists and issues, even those of the contemporary period. In the catalog for Tempo, Paulo Herkenhoff doesn’t acknowledge Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ gay identity in relation to his work Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1991). In discussing the two not quite synchronized clocks hanging side by side, Herkenhoff hints that the work is about simultaneous orgasm, “the attainment of pleasure”, but notes rather vaguely that the slight difference between the second hands indicates the “limits of desire”. However, when cross-referencing the same work with Robert Storr’s On Edge, one discovers “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) being discussed in the context of Gonzalez-Torres’ lover Ross Laycock, who “was stricken with disease [AIDS] not long before this piece was made (60).” Storr sadly notes the “daily occurrence” of death for Torres’ “generation of gay men.” Storr’s observations are in keeping with the dominant reading of Perfect Lovers as AIDS allegory: the clocks will stop when the battery runs out. In this context, Herkenhoff’s reading is patently offensive.

Notably, Storr’s exhibition occurred in 1998, some four years before Tempo, so one cannot argue that the museum is following a linear narrative of social progressiveness from Tempo to On Edge. What we’re seeing here is how the interpretation of LGBT themes in exhibited works is at the mercy of individual curators, catalog contributors, or the museum’s education division. While it certainly is not desirable that museums and their staff become homogenized at the level of a corporate restaurant chain, it is troubling that there is such great vacillation from show to show with regard to what the public can expect to learn about the LGBT artists or themes being exhibited. MOMA’s own mission statement claims that the museum must “re-evaluate itself” periodically so that it “encourages openness and a willingness to evolve and change” [footnote website]. Why shouldn’t curators, catalog contributors, or the educational departments of museums be expected to operate within the boundaries of the museum’s own mission statements? In an essay for Modern Art Despite Modernism (2000), Robert Storr writes that the vigorous presence of gay artists, such as Marsden Hartley and Paul Cadmus, before World War II “is a reminder that in times when intolerance of homosexuality ran high even among ‘progressives,’ the avant-garde was in many instances a haven for gay painters, sculptors, and photographers—male and female—and a context in which a variety of more or less explicitly gay sensibility could be explored.” MOMA should heed the words recorded in its own curatorial record as way forward in its future representation of LGBT artists and works.

Conclusion

Analysis of exhibition catalogs and web pages reveals that New York’s major museums have many shortcomings with regard to the discussion and presentation of LGBT produced or themed art on display in special exhibitions between 1995-2005.

[Space added.]

Certain museums completely excluded or barely included LGBT artists and themed works: the New York Historical Society showed nothing with LGBT themes during the period under study; LGBT themes account for only 1.49% of the total exhibitions at the Museum of the City of New York, while the Metropolitan was barely ahead with 1.81%. Museums specializing in modern and contemporary art did not meet expectations, given the number of known LGBT artists and themed work in their exhibitions: the Museum of Modern Art (3.04%); The Whitney Museum of American Art (6.35%); and the New Museum (6.79%). The Guggenheim outstripped all other museums in the study (12.19%).

Most of the artists included in the study were “homosexual”, meaning women and men either self-identified as lesbian or gay, or are discussed as such in the public record of LGBT encyclopedias, historical or art critical publications, or news articles. Knowing that 65% of the artists were gay or lesbian, and 8% bisexual, only underscores the dismal record of the museums with regard to issues of sexuality. Moreover the sheer diversity of LGBT themes, ranging from sexual and gender expression to issues of health leave no room for doubt that LGBT themes have been significantly addressed in the art on view in New York since the mid 1990s. Artists have paid tribute to their lovers (Marsden Hartley) and their LGBT friends (Nan Goldin). Artists have explicitly explored homosexuality (Robert Mapplethorpe). Artists have critiqued gender norms (Catherine Opie and Mathew Barney). Artists have delved into the loss and suffering caused by HIV/AIDS (Felix Gonzalez-Torres).

Comparison between exhibition catalogs and web pages reveals that the museums tend to be more open about acknowledging LGBT issues in catalog essays (48.7% for catalogs, but only 17.7% for web pages). The huge gap between these figures is a problem because didactic materials on the websites are more likely to be taken from the original wall text of the exhibition. While it was not possible to gain access to the wall text during research for the report, interviews with LGBT art professionals indicate that museums significantly downplay the LGBT content or meaning of the art on display in their institutional spaces. In short, exhibition viewers are much more likely to learn about LGBT themes in exhibited works if they choose to read catalog essays, an act that involves a significantly greater time commitment and monetary expense than either viewing the exhibition in situ or on the museum’s website.

Caution should be exercised before declaring that the museums are necessarily more open in discussing the sexuality of the more recent generation of LGBT artists. The Guggenheim’s Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1995) was certainly open about the artist’s sexuality, as was MOMA’s On Edge (2000). Yet MOMA’s Tempo (2002) did not discuss the artist’s sexuality. As can been seen by the dates, the most recent exhibition is precisely the one which excluded mention of sexual orientation. Moreover, it is not possible to argue that museums are silent about the sexuality of artists who lived during a time when there were harsh legal and social penalties for being gay. For example, in comparison to Barbara Haskell’s euphemistic treatment of pre-War LGBT artists and art in The American Century, MOMA’s Robert Storr approached the artists and works of the same period with a marked degree of openness in Modern Art Despite Modernism.

The inescapable conclusion is that the policies, practices, or personal beliefs of individual curators, catalog contributors, or the museum’s education division go a long way in determining how much or how little the public will encounter about the LGBT themes of the art on display. It is troubling that there is such great vacillation from show to show and year to year. Unlike the treatment of LGBT issues within the discipline of art history or in cinema and television studies, there is no clear chronological arc of openness and inclusiveness with regard to how New York’s museums have presented LGBT artists and themed art since 1995. It should be emphatically noted that while the choices and exclusions of individuals working for museums are very important, all these separate decisions over the years add up to a pervasive institutional climate of silence that produces both great incoherence in the treatment of LGBT issues and substandard scholarship. The resulting stagnation that comes from eliminating not only cutting edge academic work—but also long established changes in scholarship—from museum catalogs and curatorial visions is a terrible loss for the art world and the public.

Forty years after the birth of the modern LGBT rights movement in New York, the conditions in several of New York’s major museums seem to be mired in a pre-Stonewall sensibility. At a historical moment that places sexuality at the forefront of a number of contemporary debates, the New York museum world’s continuing silence is baffling. Given the bottom line motivation of today’s media conglomerates, which espouse socially progressive attitudes when it is in keeping with their targeted demographics, one has to conclude that at its heart museum reticence about homosexuality is not about fear of losing money. If anything, museum-goers in New York tend to be more socially sophisticated than the average consumer of popular media. So who is holding museums back from joining the 21st century? Is it the social sensibility of certain museum directors and staff? One has to ask this question because while institutions seem faceless, it is people who decide what to exhibit and what to say about the cultural objects in their care. Given the profound influence of shifting codes of representation on venues for visual culture outside the fine arts, it is time to rethink any remaining assumptions about the disinterested nature of museum stewardship.

The failure of museums to engage in a wide swathe of art historical scholarship is of grave concern because it raises the question of historical accuracy. Failing to educate the public about the LGBT subject matter or significance of the work, or of the work’s producer, does a profound disservice to the work as a cultural document, to the LGBT community which has produced a number of greatly respected and admired artists, and to the society as a whole. A chief innovation of the LGBT civil rights movement is the act of “coming out,” and through this public speaking of LGBT identity, resisting the enforced silence that comes with homophobia. Therefore museum culture’s refusal to engage honestly with the historical record not only falsifies history, but perpetuates the belief that homosexuality is “unmentionable.” Evaluating New York museum’s representation of LGBT artists and art is thus an important aspect of the Task Force’s overall project of gaining national equality for the LGBT community.

Notes

- ↑ James Smalls, Homosexuality in Art. New York: Parkstone Press, 2003: 107-129.

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “An Overview of the Museum: Governance”, http://www.metmuseum.org/press_room/full_release.asp?prid={9FF384DF-9FEA-4220-8634-D1684C00E35D}.

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “An Overview of the Museum: Finance”, http://www.metmuseum.org/press_room/full_release.asp?prid={9FF384DF-9FEA-4220-8634-D1684C00E35D}.

- ↑ New York Historical Society, http://www.nyhistory.org.

- ↑ Museum of the City of New York, “Funders”, http://mcny.org/visit/funders.html.

- ↑ The City of the Museum of New York, “About”, http://mcny.org/visit/about.html.

- ↑ The New York Historical Society, “About N-YHS”, https://www.nyhistory.org/web/default.php?section=about_nyhs.

- ↑ Please see the section analyzing catalog essays for specific examples of how the Whitney chose to discuss Marsden Hartley’s life and work, and how the Whitney compared with MOMA in this regard.

- ↑ Tee A. Corinne, “Abbott, Berenice,” in Claude J. Summers, ed. The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2004, 2-3.

- ↑ Influenced by a range of post-structuralist or queer theories and ideas, the current generation of LGBT cultural producers and thinkers tend to reject notions of sexual identity they deem to be essentializing or reductive. From this point of view, labeling people or cultural production as “gay” or “straight” only shores up conservative notions of restrictive social identities.

- ↑ Internal draft footnote omitted.

- ↑ Broadly speaking, see the special issue devoted to LGBT issues: “We’re Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History”, Art Journal 55.4 (Winter 1996). With regard to lesbians in the arts, see: Laura Cottingham, “Notes on Lesbian”, Art Journal 55.4 (Winter 1996), 72-77; Ann Gibson, “Lesbian Identity and the Politics of Representation in Betty Parson’s Gallery”, Journal of Homosexuality 27.1/2 (September 1994), 245-270; Harmony Hammond, Lesbian Art in America. (New York: Rizzoli), 2000; Erica Rand, “Women and Other Women: One Feminist Focus for Art History”, Art Journal 50.2 (Summer 1991) 29-34.

- ↑ Lisa Dennison, Clemente (New York: Guggenheim Museum: Distributed by Harry N. Abrams), 1999.

- ↑ Judith Butler’s ground breaking theoretical work was influential in academia and the art world. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, (New York: Routledge, 1990).

- ↑ Barney received widespread coverage from major art periodicals during the mid 1990s. The journal Parkett devoted an entire issue to Barney, Artforum featured an interview with Barney, and Art in America presented a feature article. Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, “Travels in Hypertrophia,” Artforum 33.9 (May 1995), 66-71, 112, 117; Parkett 45 (1995); Jerry Saltz, “The Next Sex”, Art In America 84.10 (October 1996), 82-91.

- ↑ Since the mid 1990s, scholars have increasingly critiqued this self-representation of the museum as neutral arbiter of culture by examining the various ideological components (class, race and ethnicity, economics) behind this history. Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum (New York: Routledge), 1995; Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals inside Public Art Museums (New York: Routledge), 1995; Alan Wallach, Exhibiting Contradiction: Essays on the Art Museum in the United States (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press), 1998.

- ↑ As recently as 2005, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was asked if they would simply list a symposium on Rauschenberg and sexuality among their publicity materials for their Rauschenberg Combines exhibit. They refused, as they refused to include sexuality in any way in the exhibition itself. Conversation with Jonathan Katz, 8/26/07.

- ↑ Most of the New Museum’s catalogs were not available during the research period because they were not carried by area university libraries and the museum itself was closed because of construction.

- ↑ On Johns and Rauschenberg, see, Jonathan Katz, “The Art of Code: Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg,” Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership. Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron, eds. (London: Thames and Hudson), 1993, 189-207. On Martin, see Gavin Butt, “How New York Queered the Idea of Modern Art”, Varieties of Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 320.

- ↑ Indiana’s and Kelly’s relationship, as well as the social circle of gay artists that included Johns and Rauschenberg is discussed by Susan Elizabeth Ryan in her book, Robert Indiana: Figures of Speech (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

- ↑ “Robert Indiana, glbtq: encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, and queer culture, http://www.glbtq.com/arts/indiana_r.html.

- ↑ See Gavin Butt, “How New York Queered the Idea of Modern Art”, Varieties of Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 315-338; Jonathan Katz, “The Art of Code: Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg,” Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron, eds. (London: Thames and Hudson), 1993, 189-207.

- ↑ See Gavin Butt, “How New York Queered the Idea of Modern Art”, Varieties of Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 315-338; Gavin Butt, “Bodies of Evidence: Queering Disclosure in the Art of Jasper Johns,” Between You and Me: Queer Disclosure in the New York Art World, 1948-1963 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 136-162; Jonathan Katz, “The Art of Code: Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg,” Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership. Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron, eds. (London: Thames and Hudson), 1993, 189-207; Claude J. Summers, ed. The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2004; Jonathan Weinberg, Male Desire: The Homoerotic in American Art (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2004), 109-114.

- ↑ See Michelangelo Signorile’s “Power Outage.” New York Magazine ( March 5, 2001).

- ↑ See Jonathan Katz’ analysis of the exhibition’s many elisions, in “Rauschenberg’s Honeymoon,” Art & Text, no.16 (May/July, 1998).

- ↑ Paul Taylor, "Robert Rauschenberg:'I can't even afford my works anymore,'" Interview. vol 20, no.12 (December 1990),: 146-148.

- ↑ Both Hartley’s and Cadmus’ work is discussed in Jonathan Weinberg, Male Desire: The Homoerotic in American Art (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2004); Richard Meyer, “A Different American Scene: Paul Cadmus and the Satire of Sexuality”, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002),33-94.

- ↑ Gavin Butt, “Dishing on the Swish, or, the "Inning" of Andy Warhol,” Between You and Me: Queer Disclosure in the New York Art World, 1948-1963 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 106-135; Richard Meyer, “Most Wanted Men: Homoeroticism and the Secret of Censorship in Early Warhol”, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 95-158; Kenneth Silver, “Modes of Disclosure: The Construction of Gay Identity and the Rise of Pop,” Hand-Painted Pop: American Art in Transition, 1955-62. Russell Ferguson, ed. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art; New York: Rizzoli International, 1992) 179-203; Claude J. Summers, ed. The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2004; Jonathan Weinberg, Male Desire: The Homoerotic in American Art (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2004), 134-137.

- ↑ See, for example, Laura Cottingham, “Eating from the Dinner Party Plates and Other Myths, Metaphors, and Moments of Lesbian Enunciation in Feminism and Its Art Movement,” in Jones, Amelia, ed. Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s “Dinner Party” in Feminist Art History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

<comments />