Weena Perry: NYC Museums’, Part 2

Continued from: Weena Perry: NYC Museums’ Representation of LGBT Artists and Art, August 2007

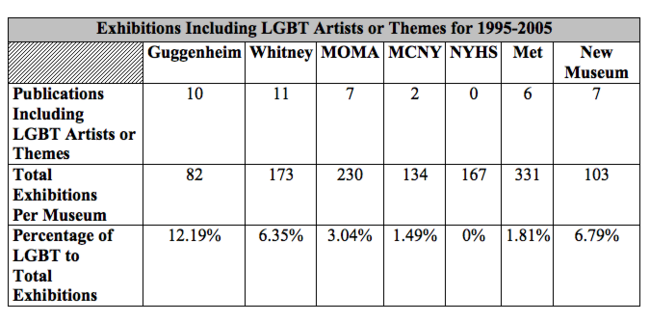

Number and Percentage of Exhibitions Including LGBT Artists or Themes

Analysis of a decade of exhibitions reveals a marked degree of under-representation of LGBT issues in the work showcased by New York’s major museums. Less than 2% of the Met’s exhibitions reference LGBT artists or themes. Even museums celebrated for cultural diversity, such as the New Museum, included only 6.79% of LGBT artists or themes over the study period. The New York Historical Society, which purports to celebrate the city’s history, has never had a show marking the contribution of New York’s extensive LGBT community to the city’s history. Given that sexual diversity became increasingly evident throughout the 20th century, it is surprising that even the Museum of Modern Art, with 3.04%, fails to mirror this great cultural shift.

Of all the museums under study, the Guggenheim devoted the most attention to LGBT artists or themes (12.19%). The New Museum (6.79%) and the Whitney (6.35%) came in a distant second and third place. The Guggenheim also produced fewer exhibitions for the period under study, 82 compared to the Whitney’s 173 and to the New Museum’s 103 exhibitions. Thus the sheer volume of exhibitions generated by larger museums should be taken into consideration when evaluating the data. On the other hand, even given the gargantuan nature of an institution such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the extremely low figure of 1.81% of LGBT artists or themes represented over the ten-year study period is a troubling statistic, especially for a museum with significant holdings in art of the modern era. Moreover, given the extensive scholarship on homoeroticism in pre-19th century Asian art one cannot accept the argument that only Western art contains LGBT themes.[1]

Perhaps the most disturbing figure is the complete absence of LGBT artists or themes from the New York Historical Society’s exhibition record for the period under study. Given that the NYHS purports to document and communicate New York history, the refusal to listen to LGBT voices and to see the contribution of the LGBT community to New York is of utmost concern. The Museum of the City of New York, with 1.49% of LGBT artists or themes, or 2 out of 134 exhibitions, barely fared better than the NYHS.

On Mission Statements, Governance, and Funding

What obligation do these institutions have to either display or discuss LGBT produced or themed art? The suppression or obfuscation of the historical record being presented to an unwitting public contradicts the common understanding of museums as ideologically neutral or even socially progressive. If art historical accuracy or moral responsibility are not sufficient reasons, then perhaps an examination of the museums’ mission and finance related statements will provide further insight into this question of obligation.

The City of New York helps fund the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a “not-for-profit institution”: “For more than a century, the City of New York and the trustees of The Metropolitan Museum of Art have been partners in bringing the Museum's services to the public. The complex of buildings in Central Park is the property of the City, and the City provides for the Museum's heat, light, and power. The City also pays for about half the cost of maintenance and security for the facility and its collections.”[2] The finance section on the Met’s website credits the City with 15% of its support.[3] The New York Historical Society’s website notes that “[p]ublic programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.”[4] The Museum of the City of New York’s website credits some of its support to the City as well: “[The MCNY] is supported in part by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and by the New York City Council, the Honorable Christine C. Quinn, Speaker.”[5] The MCNY claims that, “The Museum of the City of New York embraces the past, present, and future of New York City and celebrates the city’s cultural diversity.”[6] How does the ongoing exclusion of the LGBT community “celebrate” New York’s famed diversity? The NYHS states that, “[t]he Society is dedicated to presenting exhibitions and public programs, and fostering research that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, its holdings cover four centuries of American history, and include one of the world’s greatest collections of historical artifacts, American art and other materials documenting the history of the United States as seen through the prism of New York City and State.”[7] Yet for the last ten years New York’s LGBT history has been completely absent from its exhibition record.

While New York’s political administrations have increasingly courted the LGBT population, the city’s cultural institutions supported by municipal funds continue to discriminate against the community. Mayors and other administration officials march in the annual Gay Pride Parade—the largest of its kind in the nation. Yet the city’s public cultural institutions, which exist to represent the rich diversity of the city, continue to actively repress information about one of its most socially, culturally, economically, and politically active communities. Museums that receive funding from public sources should be accountable for exclusionary or discriminatory practices.

What about the private institutions? Perhaps these institutions have no legal obligation to the public because they are not bound by public policy, yet comparing their mission statements with practice yields questions. The Whitney Museum of American Art claims:

- Despite its early emphasis on realist art, the Whitney Museum has long been dedicated to assembling a collection that offers a comprehensive picture of twentieth-century American art. Although the collection is characterized by its breadth, it is equally recognized for its in-depth commitment to the work of a number of artists. In addition to the Hopper and Marsh collections, the Whitney has the largest body of work by Alexander Calder in any museum, ranging from the ever-popular Calder's Circus and Surrealist-inspired pieces of the 1940s to large-scale mobiles and stabiles. Other in-depth concentrations include major holdings by Marsden Hartley, Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles Burchfield, Gaston Lachaise, Louise Nevelson, and Agnes Martin.

Almost half the artists acknowledged in the mission statement are the subject of extensive LGBT studies scholarship, yet only rarely has the Whitney foregrounded the LGBT issues openly discussed in the scholarly record. If the artists merit prominent inclusion in the website mission statement, then the museum should deal forthrightly with the work. How is excluding the LGBT issues or biography of the artists evidence of the Whitney’s “in-depth commitment”?[8]

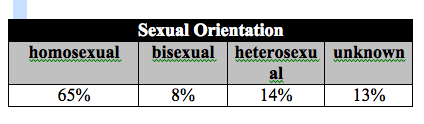

Sexual Orientation of the Artists in the Study

A significant majority of the artists included in the study were “homosexual”, meaning women and men either self-identified as lesbian or gay, or are discussed as such in the public record of LGBT encyclopedias, historical or art critical publications, or news articles. By “discussed as such,” I include artists such as Berenice Abbott, who were fairly public about their lovers or partners in their youth, yet repudiated being gay later in life.[9] Eight percent of artists in the study claimed identification or have been identified as bi-sexual, while 14% artists were heterosexual. The “unknown” category came in at 13%. This percentage is mostly comprised of younger artists included in group exhibitions who have not achieved a significant public biographical record, yet whose work explores LGBT issues.

Recurring LGBT Themes in the Work

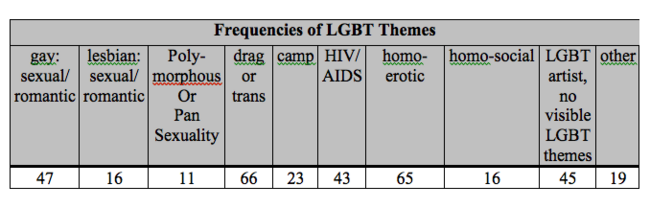

In order to ascertain the modes of public representation of LGBT artists or LGBT themed work, the study divided the exhibited works into the following thematic categories:

- gay or lesbian sexual/romantic

- polymorphously or pan sexual (to account for imaginative works that transcend dualistic biological or conceptual categories)

- HIV/AIDS

- drag or transgender

- camp

- homoerotic

- homosocial (in acknowledgement of the body of scholarship on art representing emotional or social, but not necessarily erotic, connections between people of same the gender)

- known LGBT artists whose work has no visible LGBT themes

- “other” (to allow for works that elude the above categories)

While it is difficult to affix neat labels to the wide range of complex social and political issues present in cultural production, it was necessary to assign specific categories to recurring themes in the works. After all, any community that feels under- or misrepresented in the common culture needs to demonstrate that there exist common themes, social prejudices, stereotypes or shared issues that museums must acknowledge and discuss.[10] The presence of “LGBT themes” is separate from the issue of whether or not the museums chose to interpret, de-emphasize, or simply ignore the LGBT aspects of the works of art in their exhibitions.

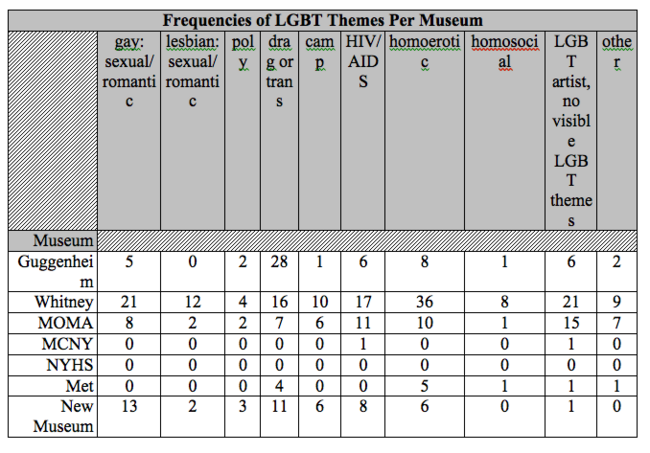

Before explicating findings, a few more details regarding the methodology for this section is necessary. When gathering data for each museum in the study, each exhibition was assigned a form on which the exhibited LGBT artists (or heterosexual artists showing LGBT themed works) were noted individually by name. (This separation was especially crucial when managing data for group exhibitions.) After examining the listed or pictured works for each artist, each applicable theme was checked off. The “yes” frequencies apply to the artist; not to individual works of art. For example, the Nan Goldin exhibition, I’ll be your Mirror (1996) at the Whitney, received one “yes” per each of the following LGBT thematic categories: gay: sexual/romantic, lesbian: sexual/romantic; drag or trans; HIV/AIDS; homoerotic; and homosocial. However, as an institution, the Whitney received 21 “yeses” for gay: sexual/romantic, meaning that 21 artists (or artists’ collectives working under a single name) exhibited work that dealt with sexual or romantic subject matter between men.[11]

However, when all the museums of the study were tabulated, there were 47 “yes” frequencies for the theme, “gay: sexual/romantic”. Certain works by certain artists overlapped thematic categories, thus making it necessary to use frequencies rather than percentages when presenting the data.

The “sexual/romantic” heading recognizes the diversity of art that aims to communicate the complex emotional and sexual practices of LGBT people. Like many humans, LGBT people tend to distinguish between romantic attachment and sexual gratification. This distinction is reflected in the art. Hence, this category includes portraits of artists’ lovers or partners, such as Tchelitchew’s pen and ink portrait of his lover, Charles Henri Ford (1937) included in MOMA’s Modern Art Despite Modernism (2000). Or, consider for example, Robert Mapplethorpe’s more exuberantly raunchy photography (Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition: Photographs and Mannerist Prints at the Guggenheim, 2004).

The “sexual/romantic” category was then subdivided between “gay” (male) and “lesbian” (female) because it became quickly apparent that lesbians were being underrepresented in the exhibitions. Gay romantic or sexual subject matter occurred in 47 times, while lesbian romantic or sexual subject matter was represented by only 16 artists. Note that the Whitney showed 12 of these 16 artists who explored lesbian sexual/romantic themes. This disproportionate figure emphasizes the dismal contributions of the remaining museums: in short, except for the Whitney, there has been a long-standing—indeed flagrant—disregard of lesbian themed work. As various minorities rights groups and feminists have repeatedly observed, there exist hierarchies among the discriminated. Women have not achieved parity in the art world at large, so it is hardly surprising to discover that lesbians fall far short of the recognition that gay male artists have managed to secure.[12]

“Polymorphous or Pan Sexuality” occurred in the work of 11 artists. “Polymorphous or Pan Sexuality”, an admittedly awkward construction that splits the difference between Freudian and Neo-Pagan terminology, attempts to account for work that delves into sexual terrain yet utterly refuses to be confined to conventional sexual or love objects. For example, Francesco Clemente has produced a number of delightfully imaginative and even fantastical works that confound normative sexual categories. Clemente, a heterosexual artist, has not only produced work that evokes LGBT themes, but also had a history of interacting or collaborating with some of the most famous LGBT artists of the 20th century, including Allen Ginsberg and Andy Warhol.[13] Interestingly, another heterosexual artist, Mathew Barney, is notable for his ripe imagination, having created a number of provocative human-animal hybrids for his Creamaster Cycle.

“Drag or trans”, like the theme of polymorphous or pan sexuality, defies discrete or normative identity categories. Specifically “drag or trans” concerns works of art that enact or represent a refusal to occupy the single gender category most humans are assigned to at birth.

With a frequency of 66, “drag or trans” work takes up the largest piece of the LGBT thematic pie, even outstripping homoeroticism. Given the broadness of the cultural concept of “homoeroticism,” the fascinating possibilities of which supply the fodder for endless jokes in popular culture, how do we account for the stronger presence of the edgier “drag or trans” thematic? Logistically, this figure is strongly skewed toward a single exhibition, the Guggenheim’s Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance and Photography, an exemplary show curated by Jennifer Blessing in 1997 whose catalog included noted LGBT scholars such as Judith Halberstam. With 28 artists working in this thematic area, Rrose represents a significant percentage of the total (The Whitney, with 16 artists dealing with this theme came in a distant second.) However, one also needs to consider the broader historical context of the appearance of “drag or trans” themed art in the art world. Beginning in the mid-1990s it became fashionable to engage in gender-bending or gender critical work in the art world.[14] Notably, heterosexual artists, such as Mathew Barney, who engage in drag or trans practice for their work, receive more large-scale curatorial attention than any of the LGBT artists in the study (for example, Catherine Opie).[15] In short, before we uncritically celebrate the fluidity of gender, and castigate retrograde categorization, perhaps we should consider the ways in which non-normative practices and identities can all too often be co-opted by the mainstream to inject a little frisson of exoticism into the status quo.

Degree of interpretation or presentation of LGBT themes in exhibition catalog and online materials

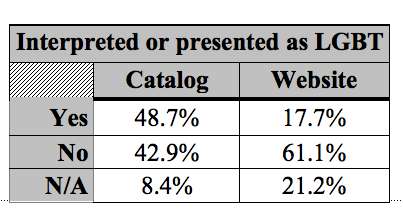

With regard to communicating LGBT themes in the work, there is a stark difference between what catalog essays are willing to say versus the didactic materials on exhibition web pages. While 48.7% of LGBT produced or themed works included in the study were presented as LGBT within the pages of exhibition catalogs, only 17.7% were presented as such within the museum web pages for the exhibitions.

This discrepancy causes grave concern because didactic materials on the websites are more likely to reflect the content of the original wall text that appeared in the exhibition. While hard data for wall text was unavailable for this phase of the study, interviews with LGBT art professionals indicate that museums significantly downplay the LGBT content or meaning of the art on display in their institutional spaces. In short, exhibition viewers are much more likely to learn about LGBT themes in exhibited works if they choose to read catalog essays, an act that involves a significantly greater time commitment and monetary expense than either viewing the exhibition in situ or on the museum’s website. Failing to educate the public about the LGBT subject matter or significance of the work, or of the work’s producer, does a profound disservice to the work as a cultural document, to the LGBT community which has produced a number of greatly respected and admired artists, and to the society as a whole. Historically, museums have represented themselves as civic institutions that not only educate societies, but also bridge divisions between diverse social groups by allowing everyone to celebrate and participate in a common culture.[16] Excluding or downplaying LGBT artists or their work violates this historic mission. Honestly communicating and presenting LGBT themes in art and an artist’s LGBT identity is thus a pressing civic and moral issue as well as one of art historical accuracy.

Degree of Interpretation or Presentation of LGBT Themes in Catalog Essays, By Museum

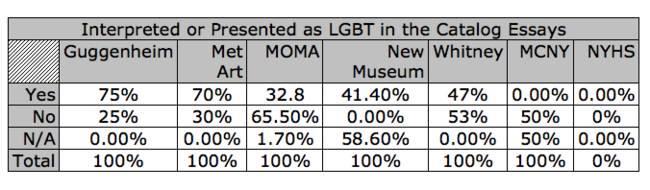

“Interpreted or Presented as LGBT in the Catalog Essays” demonstrates to what degree individual museums in the study addressed LGBT issues in their catalog essays. The “N/A” designation pertains to the percentage of unavailable catalogs, yet the exhibitions in question were included in the study because the museum posted significant information about the exhibition on its web pages. The one exception is an exhibition titled Gay Men’s Health Crisis (2001) curated at the Museum of the City of New York. While no information about the exhibition was available either in the form of a catalog or a web page, the title of the exhibition was self-evidently LGBT, so it was included in the study. Given that the Museum of the City of New York had only two LGBT artists or themed exhibitions in the study, it was especially crucial to make note of Gay Men’s Health Crisis.[17]

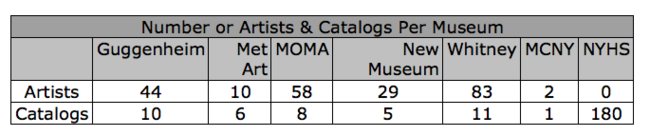

With75% in the affirmative, the Guggenheim’s catalog essays addressed LGBT issues at a higher percentage than the other museums in the study, but with 70% the Met reached a close second. However, there are other factors that need to be taken into consideration when evaluating these figures. “Count Per Museum” shows both the number of artists included in the study per museum and the number of catalogs. The Guggenheim had 44 artists in 10 catalogs, while Met had 10 artists in 6 catalogs. Moreover, 5 of the Met’s 10 eligible artists were discussed in the catalog for the exhibition, Surrealism: Desire Unbound (2002). This exhibition and the catalog originated from the Tate Gallery in London; therefore the acknowledgment of LGBT issues is the Tate’s doing, not the Met’s. The Met’s catalog essays failed to address the LGBT issues for exhibitions on Leonardo da Vinci and Christian Dior. The Thomas Eakins catalog originated from the Philadelphia Museums of art. As noted in the introduction for this report, art historian Jonathan Katz attempted several times to interest the Met in making room for a public panel that would address the body of LGBT scholarship on Eakins, but the Met refused.[18] Therefore, even though the catalog was not its creation, the Met declined opportunities to address LGBT issues related to Eakins. The Met’s catalog for Diane Arbus mentioned her photography of transvestites and LGBT people. The Met’s catalog for a Gianni Versace retrospective in 1997 was frank about the late fashion designer’s gay identity and how it impacted his work. In sum, only one of the catalogs originating from the Met significantly acknowledged the LGBT aspects of the artist or work being presented.

All other exhibitions under consideration originated with the museums being studied, thus making the percentage of catalog essays discussing LGBT issues a more accurate reflection of the museum’s/curator’s attitude toward LGBT issues than what the figures from the Met indicate. For the Whitney, 47% of the essays acknowledge LGBT issues. The New Museum follows at 41.4%. MOMA came in at 32.8%. Because the catalog for MCNY’s Gay Men’s Health Crisis was unavailable, it has a “yes” percentage of 0. (The catalog for the MCNY exhibition on Berenice Abbott, Changing New York (1997) did not acknowledge the LGBT aspects of Abbott’s biography or photography.) The New York Historical Society has a resounding 0% because none of its shows included LGBT figures or themes.

Catalog Referencing of Known LGBT Figures or LGBT Artists’ Lovers or Partners

In addition to considering the degree of inclusion of LGBT artists or themed works, it is also useful to examine other aspects of LGBT representation in museum catalog essays, including discussion of the romantic relationships of the LGBT artists included in exhibitions, and any references to other LGBT artists or historical figures (whether these figures were a part of the artists social or professional networks).

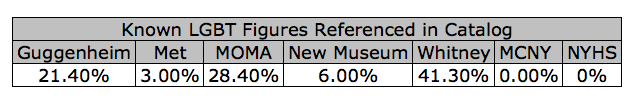

The Whitney exhibition catalogs for the period under study included a significant majority of references to known LGBT figures. With 41.3%, the Whitney easily outstripped the MOMA’s 28.4% and the Guggenheim’s 21.4%. Only 3% of the Met’s catalog’s included references to known LGBT figures, while the MCNY and NYHS had no references. As noted earlier, for the MCNY no catalog was available for one of its two LGBT eligible exhibitions.[19]

These figures demonstrate that even when these institutions do not discuss the LGBT themes of the work being exhibited, there exists a potentially rich LGBT context of social and professional associations behind the works and the works’ producers. These figures also tend to correspond to the overall willingness to the catalog essays to engage with LGBT themes in the work: see “Interpreted or Presented as LGBT in the Catalog Essays”. (Note that the Met is the primary exception because of the statistical distortion explained above.)

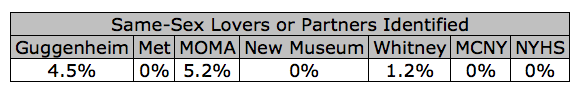

When comparing “Known LGBT Figures Referenced in Catalog” with “Same-Sex Lovers or Partners Identified”, one sees a vast difference between museums’ willingness to reference known LGBT figures (given the historical prominence of many of these figures, it is hard to avoid) and the willingness to discuss the personal romantic attachments of LGBT artists. The figures drop off radically. MOMA’s catalogs led with the low figure of 5.2%. Only 4.5% of Guggenheim’s catalogs acknowledged lovers or partners, while a mere 1.2% of the Whitney’s did. None of the other museums’ catalogs discussed the romantic attachments of their LGBT artists at all.

Examples of the Downplay or Suppression of LGBT Identities or Themes

The above examination of why the Met yielded a high “yes” percentage for LGBT interpretation even though the museum has consistently ignored LGBT artists or themes over the years, underscores an extremely important problem with regard to relying solely on statistics to illustrate the museums’ varied approaches to LGBT issues. Statistics simply do not tell the whole story. For example, they cannot convey the nuances of interpretation in catalog essays. The above figures certainly cannot demonstrate how the degree of LGBT interpretation is contingent upon the curator or on the theme of the show. For example, a show such as the Guggenheim’s Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography, curated by Jennifer Blessing in 1997, is rich with LGBT themes and artists. Its catalog included essays by well-known LGBT scholars and artists, such as Judith Halberstam and Lyle Ashton Harris. It is therefore crucial to consider in greater detail the ways in which museums downplay or suppress the LGBT identities or aspects of the work being exhibited. This section will first provide individual examples, followed by comparisons between how different museums approached the same artists or material, and then finish with cross-comparisons within museums that demonstrate how different exhibitions/curators/catalog contributors approach the same artists or themes.

Continued at: Weena Perry: NYC Museums’, Part 3

Notes

- ↑ James Smalls, Homosexuality in Art. New York: Parkstone Press, 2003: 107-129.

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “An Overview of the Museum: Governance”, http://www.metmuseum.org/press_room/full_release.asp?prid={9FF384DF-9FEA-4220-8634-D1684C00E35D}.

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “An Overview of the Museum: Finance”, http://www.metmuseum.org/press_room/full_release.asp?prid={9FF384DF-9FEA-4220-8634-D1684C00E35D}.

- ↑ New York Historical Society, http://www.nyhistory.org.

- ↑ Museum of the City of New York, “Funders”, http://mcny.org/visit/funders.html.

- ↑ The City of the Museum of New York, “About”, http://mcny.org/visit/about.html.

- ↑ The New York Historical Society, “About N-YHS”, https://www.nyhistory.org/web/default.php?section=about_nyhs.

- ↑ Please see the section analyzing catalog essays for specific examples of how the Whitney chose to discuss Marsden Hartley’s life and work, and how the Whitney compared with MOMA in this regard.

- ↑ Tee A. Corinne, “Abbott, Berenice,” in Claude J. Summers, ed. The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. San Francisco: Cleis Press, 2004, 2-3.

- ↑ Influenced by a range of post-structuralist or queer theories and ideas, the current generation of LGBT cultural producers and thinkers tend to reject notions of sexual identity they deem to be essentializing or reductive. From this point of view, labeling people or cultural production as “gay” or “straight” only shores up conservative notions of restrictive social identities.

- ↑ Internal draft footnote omitted.

- ↑ Broadly speaking, see the special issue devoted to LGBT issues: “We’re Here: Gay and Lesbian Presence in Art and Art History”, Art Journal 55.4 (Winter 1996). With regard to lesbians in the arts, see: Laura Cottingham, “Notes on Lesbian”, Art Journal 55.4 (Winter 1996), 72-77; Ann Gibson, “Lesbian Identity and the Politics of Representation in Betty Parson’s Gallery”, Journal of Homosexuality 27.1/2 (September 1994), 245-270; Harmony Hammond, Lesbian Art in America. (New York: Rizzoli), 2000; Erica Rand, “Women and Other Women: One Feminist Focus for Art History”, Art Journal 50.2 (Summer 1991) 29-34.

- ↑ Lisa Dennison, Clemente (New York: Guggenheim Museum: Distributed by Harry N. Abrams), 1999.

- ↑ Judith Butler’s ground breaking theoretical work was influential in academia and the art world. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, (New York: Routledge, 1990).

- ↑ Barney received widespread coverage from major art periodicals during the mid 1990s. The journal Parkett devoted an entire issue to Barney, Artforum featured an interview with Barney, and Art in America presented a feature article. Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, “Travels in Hypertrophia,” Artforum 33.9 (May 1995), 66-71, 112, 117; Parkett 45 (1995); Jerry Saltz, “The Next Sex”, Art In America 84.10 (October 1996), 82-91.

- ↑ Since the mid 1990s, scholars have increasingly critiqued this self-representation of the museum as neutral arbiter of culture by examining the various ideological components (class, race and ethnicity, economics) behind this history. Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum (New York: Routledge), 1995; Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals inside Public Art Museums (New York: Routledge), 1995; Alan Wallach, Exhibiting Contradiction: Essays on the Art Museum in the United States (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press), 1998.

- ↑ Noted added by OutHistory.org, February 21, 2012: See Jean Carolomusto and Jane Rosett: "Gay Men's Health Crisis: 20 Years Fighting for People with H.I.V./AIDS", April 21-September 10, 2001, an Exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York.

- ↑ As recently as 2005, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was asked if they would simply list a symposium on Rauschenberg and sexuality among their publicity materials for their Rauschenberg Combines exhibit. They refused, as they refused to include sexuality in any way in the exhibition itself. Conversation with Jonathan Katz, 8/26/07.

- ↑ Most of the New Museum’s catalogs were not available during the research period because they were not carried by area university libraries and the museum itself was closed because of construction.