1970’s-1980’s: Challenging the Conspiracy of Silence and Working Together as a Community

Beginnings of the Club:

Back in 1971, it had only been a couple of years since the Compton's Cafeteria Riot and Stonewall Riots; homosexuality was still registered as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association; the modern Women’s Movement was just forming; President Richard Nixon was playing to his “silent majority”; and the issue of homosexuality was still thought of in the popular consciousness as “The Love That Dare Not Speak its Name.” [1] [2] [3]

At this time, 'gay people' (including women, men and transgender people who frequently referred to the community in this period as a 'gay movement'), all faced widespread cultural stigma and the high probability that they could be fired, expelled from families, and subject to violence for simply coming out. [4] To even speak of gayness was taboo. This environment constituted a ‘conspiracy of silence’ where the culture had established rules that any deviation from perceived normalcy related to gender and sex was considered pathological, immoral and criminal. At this time and in this hostile environment, for gay people to sign up publicly for a 'gay democratic club' and for politicians to be associated with the issue of homosexuality, was an act of bravery.

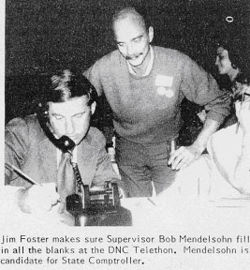

Jim Foster founded the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club in December 1971.[5] [6] Foster was a gay rights activist who had been organizing with the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) to elect pro-gay candidates in San Francisco since SIR was formed in 1964.[7] Prior to Alice there had been a few gay and lesbian advocacy groups such as SIR, the Daughters of Bilitis, the Mattachine Society and others, but gay political goals had never been incorporated directly into the platform of a major American political party.[8] [9] In 1971 Foster chartered Alice to initiate gay advocacy within the Democratic Party and started a collaborative relationship that continues to this day. [10]

Why Alice B. Toklas?

Alice B. Toklas was the partner of the famous writer Gertrude Stein.[11] The original 20 members of the Club chose Alice B. Toklas because the name served as a code to protect the confidentiality of members. Saying you were a “member of Alice” was like saying “I’m a friend of Dorothy” – only gay people would know that the “Alice” club referred to gay people.[12]

Alice's first political Campaign - 1972 McGovern vs. Nixon

Alice and Jim Foster played an important role in the Democratic Party's selection of George McGovern as the Democratic Party candidate of 1972.[13] Alice endorsed McGovern, opened a ‘McGovern for President’ campaign office, and became a Bay Area political operation for McGovern in one of the Democratic strongholds in the state of California. At a critical point in the campaign, Foster helped implement a midnight signature gathering campaign in San Francisco gay bars in advance of the state primary deadline that helped McGovern be the first candidate to submit the required signatures that morning. This placed McGovern’s name first on the list of candidates on the California ballot. [14] McGovern won California with a 5-point edge over Hubert Humphrey, and ballot placement was considered one of the reasons for his win.[15]

1972 Democratic Convention - First Attempt to put Gay Rights Plank in Democratic Party Platform

After McGovern became the candidate, Foster also represented Alice at the Democratic Party National Convention of 1972, and brought a "Gay Liberation Plank" to the national platform committee.[16] This motion was extremely significant for the Democratic Party because it brought gay rights policy before the national party for the first time ever. Unfortunately, the Democratic Party was not yet ready to adopt gay rights in its platform. Kathy Wilch, a speaker at the Democratic National Convention, gave a divisive speech opposing the Gay Liberation Plank and halted approval of its inclusion in the Democratic Party Platform. This action angered many gay activists, prompting McGovern to send a letter clarifying:

McGovern didn’t specifically say he supported gay rights, but in referencing the Wilch incident, he included gay rights in the broader context of civil rights, which was a victory. Gay rights had never been recognized as civil rights by a previous national party leader. Alice and Jim Foster's platform effort thus initiated a national effort to incorporate gay rights within the Democratic Party platform, and this relationship between the gay community and the Democratic Party would continue and grow for decades.

1973 – A club of professional advocates working from the inside

The people who started Alice were experienced in politics, many of them working previously for the Society for Individual Rights. Jim Foster, Jack Hubbs, Steve Swanson and Tere Roderick, the original officers, got the club off to a quick start. The club began raising “Dollars for Democrats”, started a door-to-door canvassing program, and outreached to Democratic Party members, including Supervisor Dorothy von Beroldingen, Supervisor Quentin Kopp, Supervisor Peter Tamaras, Senator Milton Marks, Senator George Moscone, and other elected officials.[18] [19] [20] At that time, Jim Foster built an especially close relationship with one of California’s most successful politicians: Dianne Feinstein. [21]

Early Political Successes

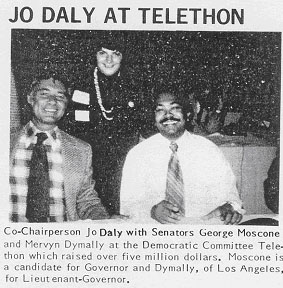

In 1969, Foster invited Supervisorial candidate Dianne Feinstein to meet with the Society for Individual Rights for her 1970 first race for Supervisor. After Feinstein was elected in 1970, Jim Foster requested that she introduce legislation to add the words “sex and sexual orientation” to the city’s non-discrimination ordinance. In 1973, Supervisor Feinstein introduced and passed the legislation at Alice's urging. Following this action, Supervisor Dorothy von Beroldingen, another close ally of Foster’s, appointed Alice member Jo Daly to a television oversight commission, a first for the City, and paving the way for lesbians and gay men to be appointed to public positions in San Francisco in later years.

Police issues:

A major concern of the club in the early years was police harassment and substandard conditions in the San Francisco County jail. Gay men and lesbians dealt with police harassment issues with raids on bars and mistreatment by officers of people in the community. The jails were also a highly unsafe environment for gay detainees and the club made it a priority to change conditions in the jails. Jim Foster wrote Mayor Alioto a letter on behalf of the club criticizing him for not doing enough to address the problem of poor jail facilities.[22] In this time, Alice began a long relationship with Sheriff Michael Hennessey who became a friend of the club, often performing as a disc jockey at the clubs annual holiday party. Hennessey worked with the community to institute changes in holding conditions for gay inmates.[23]

Marijuana:

Although the concept of “medical marijuana” was not a common political concept in this era, Alice supported efforts to decriminalize the overall possession and cultivation of marijuana.[24]

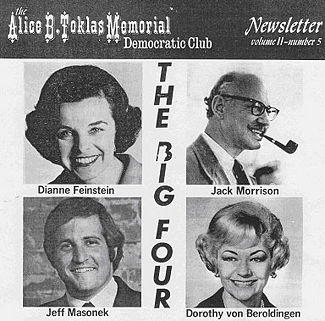

The “Big Four”

In November 1973, Alice worked to elect Dianne Feinstein, Jack Morrison, Jeff Masonek and Dorothy von Beroldingen to the Board of Supervisors. It was the first “Alice Slate” of candidates, and became a model for future efforts.

1974-1977 Post Watergate Era – Beginnings of Political Change:

With Richard Nixon’s resignation and the wind blowing at the back of Democrats, it was an exciting time. Jo Daly and Jim Foster went to the 1976 Democratic National Convention in New York, representing Alice. Despite the excitement about Democrats heading towards a win, Gay people were upset at the removal of the gay rights plank from the Democratic Platform to avoid ‘controversy.’ Gay protesters organized outside of the convention hall while Jo and Jim registered their disappointment to other delegates inside the convention. The ‘Conspiracy of Silence’ suppressing advocacy for gay rights on the national political level continued to be a pervasive stance of the Democratic Party during this era. [25] [26]

<youtube>FJNe4OhnWS8</youtube>

After the Democratic Convention, Carter made some efforts to reach out to lesbian and gay constituents through adult media. Playboy Magazine released an interview where Carter made it clear that he would sign a bill to extend equal rights to gay people, and his wife said at the time “I do not think that homosexuals should be harassed.” Carter’s choice of Playboy Magazine as the context for discussing gay rights cloaked gay rights in an adult context, and reinforced the idea that gayness is strictly about sex, but Carter’s outreach was an important start for a Democratic Party that was still finding its way on the issue of gay rights. It was the first time a Presidential candidate specifically committed to support gay rights legislation and this began to break the ‘conspiracy of silence’ surrounding the issue.[27] [28]

Huge Victory in California - Decriminalizing Homosexuality

One of the important victories for gay rights during the post Watergate era, was Willie Brown’s passage of “consensual sex legislation”, Assembly Bill 489. The 1975 bill removed California’s anti-sodomy laws that criminalized sex between consenting adults of the same gender. Sodomy laws had long been used in states around the nation to criminalize homosexuality.[29] While the laws had been used in practice sporadically, the practical impact was to silence lesbians and gay men about their sexuality. If someone came out about being gay and having a partner, sodomy laws made it that this person was in effect admitting to being a criminal. Since the formation of Alice, the organization had been working closely with Willie Brown to remove California’s sodomy laws. Passage of this legislation marked an important step in protecting the civil rights of gay people and an important legislative victory for Alice.

Alice in 1977

With the election of President Carter, the passage of Willie Brown’s consensual sex acts legislation, and the election of Alice’s slate of candidates, Alice became better known to the community. With all of this success, more people wanted to get involved in politics and the Alice B. Toklas Club. An election was held in 1977 for Club President, and membership grew significantly. 107 members showed up to vote for the elections and 26 members were elected as officers to the club. With these elections, Alice’s moderate, professional insider style became a sore point for many in the community who felt the club didn’t speak for them at that time.

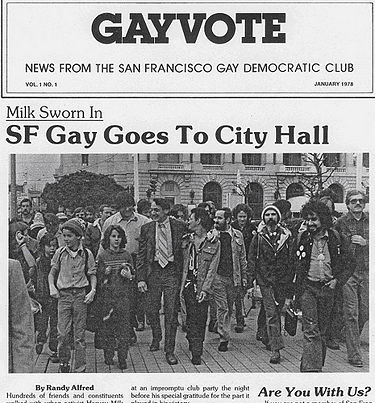

1977-1978 – the Moscone / Milk Period:

Social change brings about the most raw of human emotions and Harvey Milk’s rise to power awakened the city, bringing about new possibilities, and unfortunately new hostilities that had not been experienced in the past.

After two unsuccessful bids for Supervisor in 1973 and 1975, Harvey Milk was elected Supervisor after a new system of district elections was established in 1977. Known as the “Mayor of Castro Street”, Harvey was the first openly gay man elected to the Board of Supervisors, and he won as a grassroots candidate without the support of Alice. Members of Alice believed Harvey was too left in his politics to win, so the Club backed another gay candidate, Rick Stokes. But Harvey did win the election and made history, leaving Alice to consider its decision. One important historic aspect of Milk’s win was the recognition that grassroots politics could be successful. Alice members believed that politics was an ‘insider’ game, and that outsiders couldn’t make it into positions of power. Milk’s win disproved this and set about a rethinking of San Francisco politics for years to come.

Because Alice did not support Harvey, his supporters formed the “Gay Democratic Club” which eventually became the Harvey Milk Democratic Club after Harvey was assassinated. The ‘Milk Club’ ultimately became the left-leaning voice in LGBT politics for the city, while Alice became positioned as the ‘moderate’ voice in LGBT politics. A third club, the Stonewall Democratic Club, formed in Los Angeles and established chapters all over the country, with a San Francisco chapter established for much of the 1970's and 1980's. This club also became quite influential in San Francisco politics for some time, especially under the leadership of Gary Parker. With Stonewall and Milk, San Francisco now had three clubs for gay activists to choose from, whereas Alice had been the only game in town just a few years before. [30] [31] [32] [33] [34]

In 1977, when Harvey Milk and George Moscone were newly elected, the Alice B. Toklas Club met with Mayor Moscone. At this meeting he made commitments to Alice members about many issues:[35] [36]

- Police Commission: The Mayor agreed to appoint a gay person to the city Police Commission. He also praised the Toklas club for its resolution in support of Police Chief Charles Gain, a liberal police chief he appointed.

- Community Center: Moscone supported city funding for the development of a Gay Community Center, explaining that the Center at 330 Grove was in a building that was to be torn down for construction of the Performing Arts Center. He promised funds would be made available.

- Mayor’s Open Door: The Mayor established himself as a gay political ally, encouraging activists to work with Supervisor Harvey Milk to advance pro-gay legislation for him to sign. He also announced he had out gay people on his staff that would work with the community on community goals.

- Pride Funding: He said he favored city funding of the annual Gay Freedom Day Parade from the city hotel tax, a long-time goal of the community.

- Unity: Moscone urged Alice members to put aside their feelings that were evident from the campaign about Harvey Milk and to unite behind the winner for progress that could benefit the gay community.

Political Action and Progress:

1978 was a year of clashes between the newly active “religious right” and the “feminist left.” Five years after the Supreme Court made it’s ruling on Roe vs. Wade, the religious right began to organize all over the country, linking feminism and gay rights as shared targets in their cultural war. Jerry Falwell created his “Moral Majority”[37] and Anita Bryant waged a Save our Children campaign in Florida, while in California, State Senator Briggs jumped into the act by placing his Measure 6 on the ballot to ban gay people from teaching. The “No on 6 Campaign” backfired on Briggs and turned out to be a huge success story for LGBT Californians. Briggs lost his initiative after Alice and other LGBT organizations rallied together across the state. The campaign became a context for training young activists and supported networking among LGBT organizations. The conservative loss temporarily slowed the religious right’s crusade against gays. Progress was made on other fronts that year as well. The American Psychiatric Association finally removed homosexuality from its list of pathologies in 1978, which was a crucial step in helping American culture to shift its attitudes towards gay men and lesbians. [38] [39] [40] [41]

Violence and Turmoil:

While some progress was made in 1978, ultimately the year will be remembered most for its great tragedies. On November 27th, 1978, Supervisor Dan White climbed through an open window of City Hall and gunned down Supervisor Harvey Milk as well as Mayor George Moscone. It was a day when everyone grieved and the assassination changed San Francisco forever.

<youtube>oUB-RCNBDnk</youtube>

Dan White assassinated Milk and Moscone just days after the Mayor signed into law Milk’s Gay Rights Ordinance that White opposed. The LGBT Community held a massive, peaceful candle light vigil in Harvey’s memory following news of the murders. Later that year, White was brought to trial outside of San Francisco, and a suburban jury found him guilty of “voluntary manslaughter” and gave White 7 years in prison, a sentence widely criticized as too lenient. The jury supported the verdict on the grounds that he had eaten too many Twinkies and his blood sugar was so high, that he snapped and went temporarily insane. This infamous “Twinkie” defense sparked outrage within the LGBT community, for justice had not been done. Following the verdict, the “White Night Riots” broke out in San Francisco, and over 160 people ended up in the hospital. The riots directed anger at the SFPD, as Dan White had been a former police officer, and a string of police related incidents occurring around the time of the verdict led to an environment of tension between the community and the police. (For more about the Police and LGBT community tensions at that time, Uncle Donald’s Castro Street history has some interesting information: http://thecastro.net/milk/whitenight.html )

Amidst all of this turmoil, the leadership of Alice was torn about how to respond. Club President Steve Walters remarked:

As Walters mentioned, a string of issues had been creating tension between the community and the SFPD. The Pegs Place incident involved officers entering a lesbian establishment and assaulting women patrons with little action taken afterwards by the SFPD to respond to the incident. Walters and other members of the community charged that the SFPD had ‘whitewashed’ the facts of the Dan White case to protect one of their former officers. With anger mounting over all of these police issues, Alice became even more intensely focused on the issue of police misconduct, writing letters to the Mayor and requesting action to address the situation. [43] [44] [45]

The Early 80’s – Growing Pains, Separatism, and Different Agendas.

Lesbians and gay men shared some common political goals in the early 80’s (such as supporting Senator Art Agnos’s Assembly Bill 1, banning job discrimination against gays and lesbians), but issues such as economic justice for women and gay men’s sexual revolution came to be viewed at times as conflicting sets of priorities. When members of the community were appointed to positions of power, people began to raise questions such as “Can gay men in power truly speak for lesbians?” or “Are lesbians truly sensitive to the issues of importance to gay men?”

Former Alice Co-Chair Jo Daly was the first member of the lesbian and gay community to be appointed to the San Francisco Police Commission, but Alice member Bruce Petit wrote a letter to the club raising concerns about her appointment that echoed many of the divisions of the time.[46] He said:

Bruce Petit continued his letter, quoting lesbian Police Commissioner Jo Daly as saying:

The tension between lesbians and gay men in this period was heated, and some of the accusations on both sides now seem unfair. The conflicts were perhaps especially acrimonious in Alice because male leadership had up to that point dominated the club. But despite the divisions that erupted at this time, there were also important unique perspectives that were affirmed out of that discourse. The community began to affirm that women have a truly unique perspective from men, and people of both genders have unique contributions to make. “Gay” was no longer used as an umbrella term for the community – "gay" became a word largely designated for men, and "lesbian" became an important, distinctive term of choice for women. [48]

Women in Leadership Positions

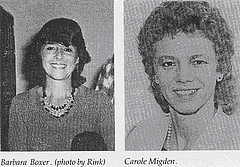

One of the most significant areas of progress for the community in the early 80’s was the rise of women to leadership positions, beginning the careers of some women who would go on to the highest offices in the nation. Barbara Boxer was elected to congress with outspoken support for LGBT issues as a central part of her campaign message.[49]

Carole Migden became the President of the Harvey Milk Democratic Club and ran for Community College Board, laying the groundwork for her later Board of Supervisors, Assembly and State Senate races.

Because of the male dominance of gay democratic clubs in the early years, lesbians worked outside of the Democratic Club system to become politically active in their own right. After Harvey Milk was assassinated and Harry Britt was appointed as his replacement on the Board of Supervisors, there was a feeling among many women that a woman should have been appointed to support gender balanced leadership. Out of the frustration of many women at being held out of political office, a group of politically active women formed the Lesbian Agenda for Action. Women like Roma Guy, Pat Norman, Martha Knutzen, Fran Kipnis and Carole Migden began to work outside the democratic club establishment in this organization as a way to assert power outside of a system that was heavily dominated by men. Out of this activism, Carole Migden eventually became the chair of the Democratic Party bringing gay staff with her. Roger Sanders, her staffer, computerized the Democratic Party system and helped her modernize the Democratic Party’s voter turnout process. [50] [51] [52]

District Elections:

After the Milk/Moscone assassinations, San Francisco moved back to citywide elections for supervisorial races. It was believed by some that district elections were a large part of the divisiveness that led to Milk’s assassination. Others felt that district elections were crucial to representing San Francisco’s diversity. Alice membership overwhelmingly supported the concept of district elections in 1980, with 200 members voting to support district elections and only two members dissenting.

1980 Democratic National Platform:

Alice worked very closely with the Harvey Milk Democratic Club in 1980 to successfully lobby Jimmy Carter (with the help of Mayor Feinstein) to include a gay plank in the Democratic Platform.[53] [54] The convention that year had a record 71 openly lesbian and gay delegates, with 17 coming from California. Alice Delegates included Harry Britt, Gwenn Craig, Jim Foster, Bill Kraus and Anne Kronenberg (one of Harvey Milk’s Aides).[55] [56] Mike Thistle went on behalf of the Milk Club and Alice member Larry Eppinette attended as a Carter delegate. Alice also sent many non-gay delegates including Kevin Shelley, among others. [57]

Fighting Police Entrapment:

Law enforcement issues continued to be a major issue of concern for Alice, as Senator John Foran authored SB 1216 to legalize police entrapment and require that a defendant prove he/she is of ‘good character’, not predisposed to commit a crime, if loitering. [58] [59]

Gay Men campaigning for office:

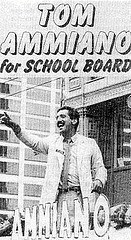

John Newmeyer became California's first openly gay man to run for congress in the 2nd District, and Alice endorsed his unsuccessful, but historic first bid.[60] Tom Ammiano ran for School Board for the first time in 1980, starting a long career in San Francisco politics, and Alice endorsed Tom in his first race. [61] Harry Britt was also appointed by Dianne Feinstein to replace Harvey Milk in office. This appointment was a source of contention for some in the community as many women felt that Ann Kronenberg, Harvey Milk’s legislative aide, should have been appointed to office to support gender balance. Britt continued to serve on the Board in the 1980’s focusing particularly on tenant’s rights issues.

Alice comes out officially as a “Gay Democratic Club” under Club President Connie O’Conner

During the early eighties Connie O’Conner was elected President of Alice and ran a slate of candidates for the Democratic County Central Committee. Louise Minnick, Randy Stallings and Connie O’Conner all won as Alice’s candidates in 1980. Connie also successfully made a motion to change the name of the club to the “Alice B. Toklas Gay Democratic Club.” This was very controversial at the time and many longtime Alice members such as Jim Foster and Robert Barnes argued that straight club members might feel alienated if the club was explicitly identified as a “gay democratic club”. Alice voted to change its name and move towards greater openness, while straight San Francisco allies continue to this day to sign up to be a part of Alice.

Alice wins seats on the San Francisco Democratic Central Committee

In 1980 Under the leadership of club President Connie O'Conner, Alice ran a slate of candidates for the Democratic County Central Committee and Louise Minnick, Randy Stallings and Connie O'Conner won seats on the committee. Previously only Milk club members like Ron Huberman and Gwen Craig represented the LGBT community on this committee.

Mayor Feinstein Recall Fight

In 1983, a heated battle ensued over attempts to recall Mayor Feinstein, with recall supporters citing her veto of domestic partners legislation and her support of landlords over tenants. Anti-recall supporters cited Feinstein’s longtime support for gay legislation and her willingness to put funds towards helping people with KS and AIDS at the very beginning of the epidemic. Alice voted 137 to 73 to oppose the recall effort and became very active in fighting the recall. Afterward, Feinstein was very grateful to Alice and instituted regular meetings with the club to keep in communication with the community about issues. [62] [63] [64] [65]

HIV and AIDS – The Total Focus of the Mid 1980’s and Early 90’s

The fight over the Feinstein recall was one of the last divisive fights between left and moderate LGBT democrats for a while, as the energy and focus had to go 100% to saving lives. San Francisco was hit especially hard by the AIDS epidemic and some of our brightest people in the community were lost. With them went much knowledge and skill that could be shared and passed down in the community. Many died early in the epidemic, such as the Founder of Alice, Jim Foster and former Alice President Robert Cramer who passed away just a few years before protease inhibitors were introduced.[66] Many continued to die after 1994, and this had enormous impact on the community. Tony Leone, a longtime member of Alice, and a dedicated activist for gay rights, passed away in 1999. Dick Pabich, the legislative aide to Harvey Milk who went on to become a campaign consultant to Carole Migden passed away in 2000.[67] Many friends in politics of these brilliant, dedicated people wondered how they could continue without their guidance and years of experience. A whole generation of knowledge was lost.

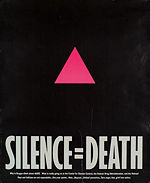

Alice jumped into the fight against AIDS early, as friends were dying, and the Federal Government was being completely unresponsive. Bay Area representatives Phil Burton and Barbara Boxer worked tirelessly to get federal support, while President Reagan still refused to even mention the word AIDS. It was a battle to get government to pay attention about something that was killing our community. As a result of this, a new slogan became popular among activists after the formation of ACT UP in 1987: “Silence Equals Death”. Activism against AIDS would increasingly be shaped as a direct battle between those who perpetuated the Conspiracy of Silence, and those who recognized that silence could kill them. [68] [69] [70] [71] [72]

The 1984 Democratic Convention in San Francisco

In 1984 the Democratic Convention was held in San Francisco three years after the initial discovery of HIV/AIDS and long before effective treatments were available. Alice representatives Sal Rosselli and Connie O’Conner were both elected as openly gay Gary Hart delegates to the Convention, and they watched Jesse Jackson speak to the convention floor after his first historic run for President. (Four years later Jackson would make his Rainbow Coalition Speech at the 1988 Convention where he famously included “gay Americans” as part of the Rainbow Coalition). Walter Mondale and Michael Dukakis both lost their elections, but progress continued for the gay and lesbian community as the national Democratic Party began to publicly include the community as part of their public agenda. [73] [74] [75]

Despite progress on some fronts, the fight against AIDS continued to be enormous and at sometimes overwhelming for the members of Alice. Club President Sal Rosselli wrote in the January 1985 edition of Alice Reports:[76] [77]

By 1985, as can be seen in this statement, Alice was challenged by the fight against AIDS. After a depressing election loss against Ronald Reagan, and continuing struggles to save friends with few treatments available, these were difficult times. Alice’s primary focus would continue to be fighting AIDS until the partial success of halting the virus came with protease inhibitors in the mid ‘90’s, which allowed for a broadening of the political agenda.

The Larouche Initiative:

Alice and AIDS activists did not get a reprieve after 1985 – things got worse before they got better. In 1986, Lyndon Larouche capitalized on AIDS-phobia and placed his infamous Proposition 64 on the ballot to quarantine people with AIDS, using the clearly faulty logic that AIDS could be spread by mosquitoes. Even in the early stages of the virus, it was obvious that mosquitoes could not spread the disease; otherwise it would not have disproportionately impacted specific groups. Fortunately, California voters struck down the initiative, once again sending a message to the radical right that measures like the Briggs and Larouche Initiatives would not be supported in California. Alice worked very hard to defeat the Larouche Initiative, contributing to the opposition’s success.[78]

Alice Pickets KQED over PBS Frontline Special on AIDS

In 1986 Alice became very involved in the fight against media defamation of people with AIDS under the leadership of Club President Roberto Esteves. San Francisco's local television station KQED ran a PBS Frontline news story on a man with AIDS named Fabian Bridges who they presented as a 'typhoid mary'. The reporters described Bridges as an HIV positive homosexual who had six partners a night and refused to stop having sex, regardless of his HIV status. The reporters didn't mention that Bridges continued to have sex because he was in financial dire straights and he was a prostitute. The reporters also failed to mention that they paid Bridges to set up their exploitative interview. Alice joined with the Milk Club to protest the KQED Bay Area showing of this story to fight the media stereotype of presenting people with AIDS as predators.[79] After this protest, KQED responded by appointing its first openly gay member to their community advisory board. This effort was one of the early efforts to fight media defamation of gays happening right after the formation of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) in 1985. [80]

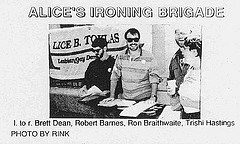

1986 Alice's endorsement critical in Jackie Speier winning Assembly Race

One of the Bay Area's most prominent leaders, Jackie Speier, became first known to many as an aide to Congressman Leo Ryan who was assassinated in the Jonestown massacre. Speier was in Guyana during the Jonestown Massacre and while attempting to shield herself from rifle and shotgun fire behind small airplane wheel, Speier was shot five times and waited 22 hours before help arrived. Speier survived and returned home from the incident going on to serve as a member of the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors. In 1986 she ran for an open seat on the California State Assembly against Mike Nevin. Nevin had secured the endorsement of the Burton/Brown San Francisco political establishment, as well as the Harvey Milk Democratic Club, but Alice was Speier's first club endorsement, and fighting against tough odds, she wound up winning. Alice's support proved critical as Speier won the race by only a few hundred votes. Speier went on to serve as a member of Congress representing nearly half of San Francisco, as well as San Mateo and the Peninsula. Alice member Ron Braithwaite organized support for Speier in her first race for Assembly and for many years Speier marched in the LGBT Pride Parade with Alice and always considered Alice to be 'her club'. [81] [82]

1987 Art Agnos wins race for Mayor

Alice shocked many in 1987 with its decision to make no endorsement in the race for Mayor between liberal Assemblyman Art Agnos and centrist Supervisor John Molinari. Molinari had been the favorite of Alice for some time and it was assumed by many that Alice would endorse him, but Agnos had many supporters who were able to block an endorsement of Molinari on a 275 to 206 vote. [83]

1990’s-2000’s: An Organized Constituency Finds its Power

Page References

- ↑ Lamberg, Lynne. Soulforce, August 12, 1998. Gay Is Okay With APA (American Psychiatric Association) Story on the history of the American Psychiatric Association 1973 removal of homosexuality from being categorized as a mental disorder.

- ↑ Wikipedia. The Modern Women’s Movement

- ↑ Phrases.org. “The Love That Dare Not Speak its Name”

- ↑ Wikipedia. Phrase "coming out"

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, December, 1972. Pgs 1-2 Discussion of the beginnings of Alice, the national election, and Alice's purpose.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Jim Foster

- ↑ Wikipedia. Society for Individual Rights (SIR) (the Society for Individual Rights was an organization formed during a period of the gay rights movement called the "Homophile" movement, and SIR would later be renamed and chartered within the Democratic Party as the Alice B Toklas Memorial Democratic Club.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Daughters of Bilitis

- ↑ Wikipedia. Mattachine Society

- ↑ Clendinen, Dudley and Nagourney, Adam. 1999. Out for Good - The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America. New York: Simon and Shuster Recounts Jim Foster organizing the Society for Individual Rights in 1964 and bringing the membership of this organization to become members of a chartered group of the Democratic Party called the "Alice B Toklas Memorial Democratic Club."

- ↑ Wikipedia. Alice B. Toklas

- ↑ Wikipedia. The Phrase “Friend of Dorothy”

- ↑ Wikipedia.George McGovern

- ↑ Clendinen, Dudley and Nagourney, Adam. 1999. Out for Good - The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America. New York. Simon and Shuster. pgs. 132-133.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Hubert Humphrey

- ↑ Democratic National Party Platform, 1972 The "Gay Plank" which Jim Foster proposed was removed. The only language the Democratic Party left that remotely relates to homosexuality was under “The Right to be Different” section, and says “Americans should be free to make their own choice of life-styles and private habits without being subject to discrimination or prosecution.”

- ↑ "Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, Vol. 1. Issue 1. Pg. 3." Letter from candidate McGovern reprinted from the August 24, 1972 Village Voice.

- ↑ Hartlab, Peter. 1999. Obituary, Dorothy von Beroldingen. San Francisco Chronicle. December 21.

- ↑ 1998. Obituary, State Senator Milton Marks. San Francisco Chronicle . December 5.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Quentin Kopp

- ↑ Wikipedia. Dianne Feinstein

- ↑ Molotsky, Irvin. 1998. Obituary, Mayor Joseph Alioto. New York Times. January 30.

- ↑ San Francisco Sheriff’s Department. Michael Hennessey. Michael Hennessey

- ↑ Wikipedia. “Medical Marijuana”

- ↑ Democratic National Party Platform, 1976 No "Gay Plank" in this 1976 Party Platform

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, July, 1976 Alice delegates report on the 1976 Democratic Convention

- ↑ Scheer, Robert. 1976. Interview with Jimmy Carter. Playboy Magazine. November.

- ↑ Carter, Jimmy. 1998. Living Faith. Three Rivers Press. Excerpt of Jimmy Carter Recollections on 1976 Election Year interview with Playboy Magazine

- ↑ Wikipedia. “Sodomy Laws”

- ↑ Harvey Milk Democratic Club. Gay Vote, January, 1978 First issue of Gay Vote, the newsletter of the Gay Democratic Club (later named the Harvey Milk Democratic Club) Cover of newsletter.

- ↑ Harvey Milk Democratic Club. Gay Vote, January, 1978 First issue of Gay Vote, the newsletter of the Gay Democratic Club, pg 2 (discusses why the club formed)

- ↑ Stonewall Democratic Club, Los Angeles. Newsletter, November 1977, pg. 1 The Stonewall Democratic Club was chartered in Los Angeles by Morris Kight in 1975. This edition of the Stonewall newsletter recounts the formation of the club. Stonewall later became a national alliance of LGBT Democratic Clubs and San Francisco had a Stonewall chapter through much of the 1970's and 1980's, but the chapter disbanded.

- ↑ Stonewall Democratic Club, Los Angeles. Newsletter, November 1977, pg. 2 Stonewall Democratic Club History continued.

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, August, 1982 "National Association of Gay and Lesbian Democratic Clubs" Founded

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, December, 1977 San Francisco Mayor George Moscone makes several public commitments to the gay community

- ↑ Wikipedia. George Moscone

- ↑ Moral Majority Coalition, The. "Moral Majority Timeline"

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, May, 1977 Alice helps organize the fight in Dade County Florida

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, July, 1975, Pgs 1-2 Backlash against consensual sex law. This backlash would build into an organized effort in following years led by State Senator Briggs to place Measure 6 on the 1978 state ballot to ban gay people from being teachers.

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, July, 1975, Pg 4 More on origins of Briggs Initiative

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, July, 1975, Pg 7 More on origins of Briggs Initiative

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, June, 1979 Recounting the Dan White trial and local upheaval + police incident at "Pegs Place", a lesbian bar.

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, December, 1978 Death of Harvey Milk, recounting his life and impact on politics

- ↑ Harvey Milk Democratic Club. Gay Vote, August, 1979 Story of Police incident at Peg's Place. (pg 1)

- ↑ Harvey Milk Democratic Club. Gay Vote, August, 1979 Story of Police incident at Peg's Place. (pg 2)

- ↑ San Francisco Women’s Building, The. Obituary, Jo Daly.

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports Newsletter, February, 1980

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, August, 1982 Gender divisions discussed

- ↑ Johnston, Robert D. Jewish Women’s Archive. Barbara Boxer

- ↑ Jabloner, Paula and Montoya, Gabriella, Online Archive of California, 1995, Guide to the Lesbian Agenda for Action Records, 1987-1991.

- ↑ BetterWorldHeroes.com. Roma Guy

- ↑ Answers.com. Pat Norman

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, August, 1980, pg 1 Democratic National Convention - 1st Adoption of "Gay Plank"

- ↑ 1980 Democratic National Party Platform Gay platform plank is under "Civil Rights" and states "All groups must be protected from discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, language, age, sex or sexual orientation.”

- ↑ Wikipedia. Bill Kraus

- ↑ 2009. Gay Russia. Interview: Anne Kronenberg remembers Harvey Milk’s fight for gay rights. August 13.

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, August, 1980, pg 2 Democratic National Convention + Carter, Reagan on Gay issues

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, August, 1981, pg 1 Police and Sheriff's Issues discussed

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, August, 1981, pg 2 Sheriff's Issues continued & National Gay Rights Bills Discussed

- ↑ John Newmeyer personal website.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Tom Ammiano

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, April, 1983 Feinstein recall fight & "Demand Cash to Fight AIDS Crisis"

- ↑ Harvey Milk Democratic Club. Gay Vote, February, 1983 Milk Club debates Feinstein Recall

- ↑ 1983. Associated Press. Mayor Feinstein Could Face Recall. January 14.

- ↑ 1983. Mayor Feinstein is Favored to Withstand Recall Effort. Associated Press.

- ↑ About.com The History of HIV Protease Inhibitors

- ↑ Pabich, Dick. San Francisco Chronicle Obituary, January 3, 2000 Harvey Milk Campaign Consultant Dick Pabich dies from AIDS-related complications.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Phil Burton

- ↑ White, Allen. 2004. Reagan's AIDS Legacy / Silence equals death. San Francisco Chronicle. June 8.

- ↑ Wikipedia. ACT UP

- ↑ Social Design Notes. “Silence Equals Death”

- ↑ Avert.History and Science of HIV/AIDS

- ↑ 1984 Democratic National Party Platform "Gay Plank" under “Chapter II, Justice, Dignity, Opportunity – Introduction” “Government has a special responsibility to those whom society has historically prevented from enjoying the benefits of full citizenship for reasons of race, religion, sex, age, national origin and ethnic heritage, sexual orientation, or disability.”

- ↑ Wikipedia. Walter Mondale

- ↑ Wikipedia. Michael Dukakis

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, January, 1985 Looking back at 1984 and fight against AIDS

- ↑ Wikipedia. Sal Rosselli

- ↑ Robert Steinbrook; Kevin Roderick; 1986. Medical Experts Assail Initiative on AIDS: Officials Dismiss Claims Made by Supporters of Larouche-backed Prop. 64. Los Angeles Times August 3.

- ↑ Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club. Alice Reports, April, 1986 Alice confronts KQED over defamatory story on man with AIDS

- ↑ Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation

- ↑ Wikipedia. Jackie Speier

- ↑ Wikipedia. Leo Ryan

- ↑ Wikipedia. Art Agnos

1990’s-2000’s: An Organized Constituency Finds its Power

Copyright (c) by Nathan Purkiss, 2010. All rights reserved. Contact nathanpurkiss@yahoo.com

<comments />