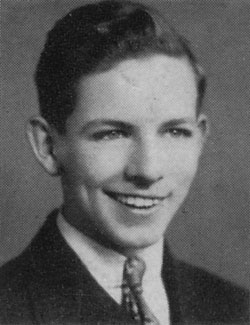

Bob Hull

Bob Hull, 1936 | |

| Born | May 31, 1918 |

|---|---|

| Died: | May 1, 1962 |

| Role: | Founder of the Mattachine Society |

Biographical Profile

by David Hughes

Submitted to C. Todd White on October 26, 2008

In November 1950, Bob Hull co-founded the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles with Harry Hay, Chuck Rowland, Dale Jennings, and Rudi Gernreich. The Mattachine set the stage for the gay liberation activism of the 1960s and 1970s, but because of his suicide in 1962, Hull wouldn’t see the movements, marches, and militancy that would soon follow.

Early Life

Bob Hull grew up in St. Louis Park, a rural suburb of Minneapolis. Neither politics nor activism were themes in his early life, but he may have participated in a 1936 student walkout in support of a popular principal. Despite being open about his homosexuality, he proposed marriage to a fellow student at music college then abruptly transferred to the University of Minnesota’s Chemistry program after her refusal. During this first term there, he met graduate student Chuck Rowland, and they became lovers briefly. Upon graduating in 1943, Hull entered graduate school and became a research assistant until leaving the University in 1947.

The Mattachine

After the war, Rowland became a Communist organizer, recruiting Hull to accompany him on house visits. At some point, the two discussed organizing homosexuals, a dream of Rowland’s since childhood. Rowland left the Communist Party in 1948 and moved to Los Angeles, followed by Hull. Still a Communist, Hull attended a local labor school through which the two met Harry Hay, who taught musicology. In mid-1950, to avoid the anti-Communist witch hunts, Rowland, Hull, and another Party member left for Mexico, intending to relocate but returning by fall. Re-enrolling in Hay’s class, Hull received from Hay a blueprint for a homophile support group, which Hull showed to Rowland and Hull’s lover Dale Jennings (another Communist). Enthusiastic about Hay’s prospectus, they met with Hay and his lover Rudi Gernreich on November 11, 1950, the first of many meetings that failed to attract other principals—until the spring of 1951 when Jim Gruber and his lover Konrad Stevens joined, bringing the core group to seven.

The Mattachine Foundation and its underground counterpart, Mattachine Society, were the manifestations of Hay’s original prospectus, which conceived of homosexuals as a cultural minority—a theoretical underpinning embraced by Rowland but questioned by Jennings and others as disregarding significant differences between individual homosexuals. Mattachine was taken from a subject of Hay’s class: a medieval “society of fools” (Hay’s original choice for a moniker) whose contrarian ways seemed a fit for the new organization. It’s possible that Hull, recalling the name from the class, suggested it in lieu of Hay’s choice—the name’s obscurity allowing for both anonymity and the opportunity for careful explanation to the curious.

Unlike Hay, Rowland, Jennings, and Stevens, Hull isn’t remembered for his involvement or commitment, but he did contribute to Mattachine by leading discussion groups (the organization’s initial stock-in-trade) and his role in the group’s written propaganda. He was nicknamed “Viceroy” of the Mattachine due to his ability in meetings to render understandable the content of heady discussions. As his involvement grew, Hull stopped attending Communist Party meetings. He also stopped seeing Dale Jennings: according to Harry Hay, it was that breakup in early 1952 that led Jennings to cruise Westlake Park, resulting in his arrest, but more significantly, leading to the cause célèbre, and court victory in June, that would put the Mattachine on the map amongst homophiles in Los Angeles, in California, and eventually in the country at large.

Mattachine Meltdown

Less than a year later, due in part to this exponential growth, the founders faced opposition by Northern California members who didn’t share the radical roots of Hay, Rowland, Hull, and Jennings. At a statewide constitutional convention in April and May 1953—held at the First Universalist Church where he later would become organist—Bob Hull is remembered as having questioned whether the founders could withstand an investigation conducted by, say, a Senate Committee tipped off by red-baiting northerners. Just as Harry Hay had left the Communist Party in 1951 for the greater good of both organizations, the core group agreed to step aside for the long-term benefit of the Mattachine. One can imagine Bob’s ex-lover Dale Jennings taking bittersweet satisfaction in this rift; early on he had questioned the notion that people who had nothing in common but their homosexuality could be seen as a cohesive “cultural minority.”

Post-Mattachine

With his departure from the Mattachine, Hull seems to have shed a skin. Leaving activism behind, he continued to socialize with people like Chuck Rowland, Jim Gruber, member Martin Block, and psychologist Evelyn Hooker. Along with his longtime best friend Stan Wit and a new (and last) lover, Hull contributed his talent to Rowland’s short-lived, homophile-friendly Church of One Brotherhood. Hull and his lover enjoyed outdoor camping, performing chamber music, and spending holidays with Hull’s relatives and with his widowed mother, Elsie, who was loving and accepting and, in fact, considered Hull’s lover to be another son.

Later Years and Death

Bob Hull is described by his last lover, a psychologist, as being a depressed type. During years in therapy, Hull’s psychiatrist actually employed an amphetamine-type stimulant in order to overcome Hull’s reluctance to open up. Returning home after these sessions, Hull was animated to distraction and used alcohol to come down—an emotional and psychological seesawing routine that, undertaken on a regular basis, surely took a toll. When his lover of seven years felt the need to separate from Hull for personal reasons, Hull was faced with either living alone, which he couldn’t abide, or seeking out a new mate, which he found daunting as he approached middle age. Although his friend Stan Witt stood by him, Hull allowed a crippling introversion, and an aversion to confrontation—nurtured in childhood by his excessively pacific mother—to prevail. Just days after finding himself single, and a month before his forty-fourth birthday, Bob Hull killed himself. It was May 1, 1962: International Workers’ Day.

References

Text by David Hughes. Copyright (©) by David Hughes, 2008. All rights reserved.

Back to Exhibit Main Page