Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Four, Sterling and Bloss: The After Years, Part 3

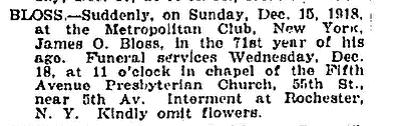

1918 (December): James Bloss Dies

There is much conjecture among the researchers about Bloss’ death. He died suddenly only six months after Sterling. He was living in the Metropolitan Club, a private gentlemen’s club a dozen blocks south of the home he had shared with Sterling for 17 years.

Why did Bloss die? Was he ill before he died? Why did he turn down Sterling’s offer to live out his years at 912 Fifth Avenue? Why did he move to his club and not move to his home in the country? Why was Bloss not buried with Sterling as Sterling had offered?

There are three theories that the researchers worked under which would explain Bloss’ actions after Sterling’s death.

First, there’s the romance theory. This theory holds that there was a loving sexual relationship between Bloss and Sterling and that even at Bloss' advanced age, he was heartbroken and lost after Sterling’s death.

Second, there is the anger theory. For whatever reason, whether it be mistreatment by Sterling, the family, associates, or Yale, at some point, Bloss became angry and wanted nothing more to do with Sterling.

Third, there is the practicality theory. This theory is predicated on the fact that despite hearsay and circumstantial evidence to the contrary, there is no conclusive evidence that, in the milieu of the early 20th century, Sterling and Bloss would behave any differently than they did, because they were nothing but exactly what they appeared to be: close friends, but friends only.

Why did Bloss die just months after Sterling's death? Some researchers say it was heartbreak or the stress on a 71-year-old man of the death of a loved one, or at the least, a very dear friend. Other researchers point out that this was the time of the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic that lead to a sudden death for an estimated 50 million people (3% of the 1.6 billion world population at that time). Could Bloss have come down with the “flu”? It would have certainly weakened the heart of a 71-year old man who already had existing heart trouble; maybe even enough to cause his heart to fail. Such a world pandemic raging at the exact time of his death is certainly hard to ignore.

The cemetery records list the cause of Bloss’ death as angina pectoris, the medical term for chest pain or discomfort due to coronary heart disease. Angina is a symptom that usually disappears rapidly and not a cause of death; but it appears that Bloss died of heart disease. Ultimately, the cause of his death is less important than the circumstances surrounding it.

Was Bloss ill at the time of Sterling’s death? The researchers theorize that at that time in July, though well past the average life span, Bloss was reasonably healthy for a man in his early 70’s with heart disease. Living in the early Twentieth Century, the average life expectancy would have been much shorter than it is today. Today, life expectancy for men is 75 years; for women, it is 80 years. In 1918, life expectancy for men was only 53 years and women's life expectancy was 54.

It certainly appears from his actions that he expected to continue looking after his business interests. Therefore, Bloss needed a New York location from which to continue those interests. Bloss was a Director of the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway Co; President and a Director of Fidelity Co. (type of business unknown); a Vice President and Director of the Sault Ste. Marie Bridge Co.; and, of course, one of the executors of Sterling’s will.

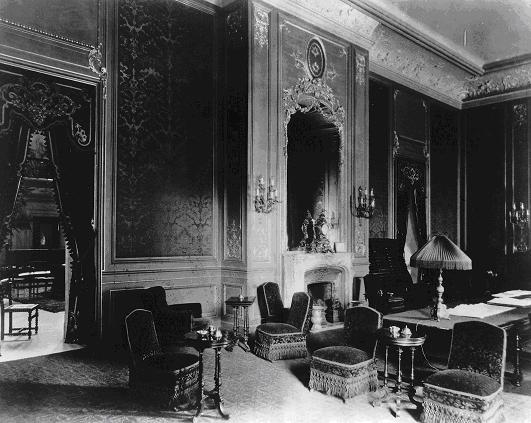

If he was healthy at the time of the move, a gentleman’s club of that time would have given him all of the benefits of living in a private residence with numerous servants, a perk that Bloss was very much used to. (Exhibit 7) Financially, Bloss was not in difficulty, but the convenience and practicality of living at his club would have appealed to a savvy businessman. Further, he could have been living at the club temporarily in anticipation of finding a residence of his own in the city.

If Bloss had been ill at the time of the move, would he have moved to a private club while trying to keep businesses running, stayed at 912 Fifth, or moved to his country home? As a negative, if he moved to the club, he would be in the constant company of business associates who would know quickly that he was ill and that could have been detrimental to his business interests.

Such a move also supports any of the theories that Bloss would have destroyed many of his and Sterling's personal papers before moving out of 912 Fifth. He was given custody of Sterling's effects and he knew someone was going to take over the house. If he had albums or large amounts of personal photos and materials relating to his relationship with Sterling, where could he have taken them to make them safe from prying eyes? Living in a private club would have limited his ability to store much material. His only other option would have been to ship it out to his country home in Rye.

Above, Interior of the Metropolitan Club near the time that Bloss would have been a member.

Why did Bloss turn down Sterling’s offer to live out his years at 912 Fifth Avenue? The romance theory doesn’t seem to apply here. We know at the time the New York Times obituary was written, they did not know what Bloss’ decision was to be. Bloss may have already made the decision at that time, or may not have known his intentions, himself.

From Sterling’s point of view, there might have been little romance involved. The practicality theory seems to apply to his own actions: Sterling intended the house eventually to go to Yale as part of the bequest. However, he had entered a condition in the process that would have allowed Bloss to live out his days in the house he lived in for 17 years, should he so choose, before the house reverted to Yale. Sterling was sentimental enough to provide for his friend, but was a lawyer and businessman who also knew that Bloss had a nice home in the country. (See Exhibit 6).

From Bloss’ point of view it’s either the anger or practicality theory: We know that Sterling had left material specifically marked for Bloss to destroy and other material specifically marked for him to keep or destroy at his option. Bloss was executor of Sterling’s personal papers, so he would have had “practical" or possibly "angry” work to do in organizing or destroying material.

At this point, we don’t know why Bloss, himself, chose to move out of 912 Fifth. Was it romance: A desire to leave a location that would have constantly reminded him of Sterling? Was it anger: Anger at something Sterling did, pressure from society, Yale or the family, either Sterling’s or his own? It’s certainly possible, but if that happened we do not know. If it was anger, it would explain abandoning 912 Fifth for his club.

But was it simply practicality: a desire, as a friend, companion and the co-executor of Sterling’s will to fulfill his required duties as quickly as possible and move on with life? Bloss may have felt a pressing responsibility to resolve his duties and thereby expedite the fate of the house and the servants who were tasked with caring for it. He knew they would need to find other situations should the house be sold, demolished, or otherwise become disposable to Yale. Perhaps he knew of an offer already on the table for the residence to be replaced by a high-rise. That would have converted the real estate to more useful and liquid cash for Yale. Of course, we can only guess.

Why wasn’t Bloss buried in Sterling’s mausoleum? It’s a known that Bloss was interred in a very simple grave with a basically nondescript stone in the family plot in Rochester. It’s also known that Sterling’s mausoleum was built in 1910, thereby giving Bloss and Sterling ten years to discuss and decide burial arrangements between them.

Obviously, the romance theory doesn’t apply here or Bloss would most probably have elected to be buried with Sterling, right? But what would be a romantic-based reason that Bloss would decline to be buried with Sterling? Did Bloss already have a burial plan in place that he didn’t have time to alter before his death? Perhaps he chose not to be buried with Sterling to protect his family from scandal. Bloss’ family possibly would have been scandalized to interr him next to another man, so that they may have made that decision for him after his death, no matter what his expressed intentions might have been. It was a very rare situation in those days for a man to be interred anywhere other than beside a spouse or in a family plot, unless in a military, Masonic or other specialized cemetery.

If it was anger at Sterling, it would explain why he declined his offer to share Sterling’s mausoleum.

Bloss wrote his final will a few weeks after Sterling’s death. Did he change it out of romance, anger, or practicality? A copy, written out by hand by a clerk in 1919 was presented to the researchers for review in a huge bound book with scores of other wills at Surrogate’s Court in Manhattan. The highlights of Bloss’ last Will and Testament, signed on August 7, 1918, shortly after Sterling's passing and a few months before his own demise:

To his sister Grace Bloss Chace of Rochester: The proceeds of any life insurance issued by Equitable to which he was beneficiary . [The researcher theorizes that this wording would have allowed for any part of Sterling's policy not yet paid out, but owing to Bloss, as of the date of Bloss’ updated will.] Further bequests to his sister Grace ran from a pearl scarf pin with diamonds and its cushion to his "marble mantle."

To his sister Harriet Elizabeth Daly, Bloss bequeathed $10,000.

To his nephews, Merwin Taylor Daly and Warren Cox Daly, his "effects, ornaments and jewelry." No specification of how these were to be divided.

To James N. Hill, one of Bloss’ executors and friends, $6,500 to be kept or distributed as Hill saw fit.

The "residue" of his presumably substantial estate was to be divided in equal shares among Grace, Merwin and Warren. His sister Harriet was not included. The only specific instruction regarding his "residue" was that his "country seat" at Harrison, N.Y. was to be sold at a price considered "reasonable and proper" by his executors.

There were no directions on the disposal of his body. If he was brokenhearted and wanted to be buried next to Sterling, if he was angry and did not want to be buried next to Sterling, or if he was indifferent or expected to be buried in the family plot, one expects he would have made his wishes known here. He could have cleared up any chance for misunderstanding of his wishes by doing so. Why didn’t he?

Was it simply the practicality theory at work? Did Bloss simply expect to be buried with his family as the natural way of things? So depending on which theory you subscribe to, either Bloss changed his mind at the last minute, someone else made the decision post-mortem for him, or he planned to be buried in Rochester all along and decline Sterling’s offer.

It must be remembered that after a death and unless specific instructions are left, the body belongs first, to a spouse, and if there is no spouse, to the next of kin. Ultimately, the final decision would have been up to Bloss’ sisters should they choose to disregard his wishes in the matter.

Bloss’ funeral was held at Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, still in existence today, and he was interred with his parents, a namesake brother, and a brother John, in Mt. Hope Cemetery, in Rochester, NY. Nearby lay his favored nephews Merwin, and Warren who grew up to be a doctor, and his sister Harriet among other assorted family members.

James O. Bloss is buried in Section U, of Mt Hope Cemetery, in Rochester, New York. Above, a recently photographed close-up of Bloss’ surprisingly humble headstone. The remaining inscription reads: James O Bloss, son of James & Eliza Bloss, Born September 30, 1847, died December 15, 1918. There is more inscription below, a feature common to Bloss family headstones, but its smaller lettering has been made indecipherable by the elements over the years.

See also:

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Research on Sterling and Bloss, MAIN PAGE

Sections of the Gruener-Wagner Research Report

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section One, Sterling and Bloss: The Early Years

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Two Sterling and Bloss: The Working Years

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Three, Sterling and Bloss: Fifth Avenue Years

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Four, Sterling and Bloss: The After Years, Part 1

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Four, Sterling and Bloss: The After Years, Part 2

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Four, Sterling and Bloss: The After Years, Part 4

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Section Four, Sterling and Bloss: The After Years, Part 5

Guides to the Gruener-Wagner Research

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Sterling and Bloss; "Guide to Locations and Parties"

Claude M. Gruener and Rick Wagner: Sterling and Bloss; "Time Line and Index"

In addition see:

John William Sterling and James Orville Bloss

Original entry on the lives of Sterling and Bloss by Jonathan Ned Katz.

James Orville Bloss: September 30, 1847-December 15, 1918

<comments />