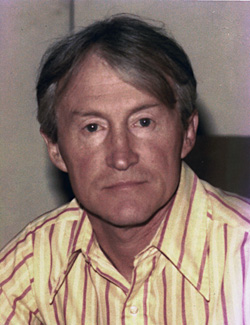

Don Slater

Text by C. Todd White, Ph.D.

Also see Don Slater’s page in the LGBT Journalists Hall of Fame and our Memorial Page on Don Slater

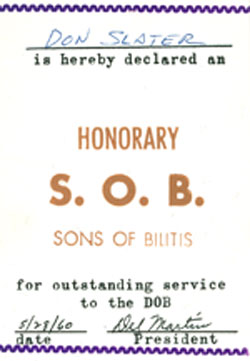

Don Slater will occasionally be found lurking like the Cheshire Cat in the nooks and crannies of the institutional history of the homophile movement. Slater was instrumental in the founding of many homophile organizations including ONE, Incorporated; ONE Institute of Homophile Studies; the Institute for the Study of Human Resources [IHSR]; and the Homosexual Information Center [HIC]. Along with his ally-cum-adversary W. Dorr Legg, Slater became a leading pioneer in the homosexual/homophile movement in California and in the rest of the United States. He is one of the most unsung heroes of the pre-gay era, yet few other activists of this time could lay claim to so many significant victories, and fewer still inspired as much hope, love, and courage in their colleagues and followers.

Young Don Slater

Don Slater was born in Pasadena on Aug. 21, 1923, first born of identical twins. His father, Warren Steven Slater, was Athletic Director of the Pasadena YMCA. Team sports and athletics were Coach Slater’s passions apart from family. He spent many years as a president of the Pasadena and Glendale YMCAs or the Los Angeles area Boys Clubs and was elected the 1956 “Dad of the Year” by the Boys Club of Oceanside.[1]

The Slater family moved frequently during the 1920s and ’30s, all over the greater Los Angeles area. Constant upheaval meant that young Slater was not able to form long-term friendships in his childhood. Though it would be difficult to track his progression through the Los Angeles schools, it is known that he spent some time in Junior High School at John Marshall in Glendale, and he graduated from Chaffey High in Capistrano Beach in 1942.[2]

Slater was a short and slender man, described as puckish by his friend Joseph Hansen.[3] He was a sensitive intellectual, nowhere near as athletic as his father. Through his passion for nature and the outdoors, Don Slater did love to swim and ski. When drafted into the army, in February of 1943, he was sent to Camp Hale, Colorado, where he trained as a ski trooper. Months after his induction, he was confined to the infirmary, “his heart beating double time.”[4] A few weeks later, Slater was honorably discharged and headed back to Los Angeles.

Through the assistance of the Army’s rehabilitation program, Slater enrolled at the University of Southern California in February 1944 to work toward a bachelor’s degree in English. Slater worked in the USC library by day as a Stack Supervisor. At night, Hansen tells us, he would hang out with Hal Bargelt and other members of the University’s “gay underground” boozing in the bars on sleazy Main Street. “He enjoyed the transvestites, and was as friendly with them and the other lost souls adrift in the gritty shadows of Main Street’s gaudy neon as he was with his fellow students by day.”[5] Slater became known as a campus rebel. He “collected traffic tickets like trophies, then decided to act liked Thoreau, refuse to pay the fines, and go to jail for civil disobedience. His position was that the state had no business telling him where he could park.”[6]

Love in Pershing Square

One spring night in 1945, when Slater was twenty-one years old, he went cruising in nearby Pershing Square, where he met a slender Hispanic boy of about sixteen named Antonio Sanchez.[7] As Slater described the meeting to Hansen, the two repeatedly bumped into each other while prowling through the bushes. ‘What! You again?” they laughed. They joked that they must have been meant for each other, and indeed, they were to remain partners until Slater’s death nearly fifty-two years later. After living together for a while in a ski lodge belonging to Slater’s parents, Slater and Sanchez moved into an apartment at 221 South Bunker Hill Avenue, in one of the Victorian mansions Slater admired. The house on Hill was a few doors west of Hope Street (and thus the title of Hansen’s biography).

In 1948, Slater again fell ill with rheumatic fever. By this time he was a senior at the University, but he was forced to from classes due to extended absences. He asked to be given a fresh start the following term. He made good use of the free time allotted him once he recovered: “Don had his Wanderjarh in the best Eugene O’Neill style, going ashore to explore the waterfronts of Oslo, Stockholm, Bremen, Le Havre, Marseilles, and other fabled ports of call.”[8] After this extended adventure, he returned to school and his boyfriend and was awarded his BA in English literature, with an emphasis on the Victorian novel.

Now a graduate, Slater donned a tie and started to work for Vroman’s bookstore in Pasadena, making fifty cents an hour. Sanchez made a better income through his musical performances at the El Paseo Inn, on Olvera Street. After getting off work at Vroman’s, Slater would often head to the El Paseo to watch Tony dance, and it made Sanchez proud to see his lover in the audience.[9] One night Slater brought a man with him named Bill Lambert, whom Slater admired for his “erudition and his way with words.” Sanchez was impressed with Lambert as well: “He had charm and poise and manner, and was clever,” he later told Hansen. It was to be a fortuitous encounter, the launch of a long and tempestuous friendship between Slater and Lambert.

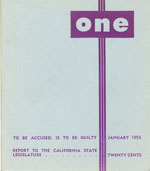

The Launch of ONE Magazine

Don Slater was hardly new to the scene when Bill Lambert, Dale Jennings, and others set out to publish ONE Magazine. Though he and Sanchez had attended a Mattachine discussion meeting, he just hadn’t really been interested in joining Harry Hay’s society and was put off by the “mystic brotherhood” talk of the early Mattachine. “‘A sewing circle,’ Don called it afterward—‘The Stitch and Bitch club.’”[10] He wanted nothing to do with Hay’s organization.

But when Slater heard talk that some wanted to create a magazine that would convey a homosexual viewpoint to the public, he and Sanchez dedicated themselves to the task. The magazine was the perfect conduit by which they could facilitate an open discussion of homosexuality and homosexual rights on as broad a level as possible—perhaps even throughout the nation. The minutes of the first meetings took place just prior to his graduation from USC and were written in his spiral class notebook.

A Passion for Books

Through the early 1960s, Slater’s primary duty was to ONE Magazine. But he was also active in building ONE’s library, which he saw as being the core of the organization, the source of homophile information and history. Slater was every bit the archivist that Jim Kepner was. He became Assistant Professor in Literature for ONE’s Educational Division, teaching courses such as Writing for Publications and a Library Workshop on “classification and use of scientific works and fiction in the homophile field.” Kepner[11] reported that Slater had graduated from USC with a degree in library science, but this is not so. Nevertheless, his cohorts at ONE appreciated him as much for his skills as a librarian as for his talents as editor. The classification system that he created with his USC cohort Jack Gibson was adopted by Kepner’s library and is still being used by some archives today.

In August of 1965, four months after ONE divided and he had moved the corporation's archives, including the Blanche M. Baker Memorial Library, from the Venice office to a new site in Universal City, Slater wrote an impassioned letter to HIC’s attorney, Ed Raiden, claiming that the library and archival materials that ONE had collected represented the true heart of the corporation. Legg’s faction had laid claim to the archives and Slater was in danger of losing his collection. “If ONE has any assets, this is it. Damn the future of its publications, but the fate of this material is important.”35 With Raiden’s help, Legg’s tactic was thwarted. Slater raised the money for the bond, as required by a judge, and the majority of ONE’s library, now called the HIC collection, has remained in the care of HIC ever since.

A Rebel With Cause

After the schism of ONE, Incorporated in 1965, Slater became the chair of the new organization, which first called itself The Tangent Group and became incorporated as the Homosexual Information Center in 1968. The HIC became federally tax-exempt in 1971. Even through the course of the split, through a prolonged and bitter dispute that caused him two solid years of persistent frustration and anguish, Slater continued to fight other battles on behalf of the movement. The most notable involved a schoolteacher named Don Odorizzi. Slater, with the assistance of Jim Schneider, was able to help Odorizzi win a significant case of Undue Influence on a schoolteacher by the Bloomfield School District. The case is still being taught in law schools today.

In 1966, Slater and Harry Hay co-chaired a meeting in HIC’s offices to plan a motorcade protest on Armed Forces Day, May 16, against the policy of not allowing homosexuals to serve in the military. Activist Vern Bullough and HIC directors Jim Schneider and Billy Glover also rode in the motorcade. CBS news broadcast brief coverage of the event that night on the evening news.

The following year, Slater assisted as HIC sponsored a production of Clare Boothe Luce’s play The Women, which drew a crowd of over 300 the night it was performed at the Embassy Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles. During the performance, police arrived and arrested Slater, who had identified himself as being “the one in charge” when so asked by the officer. According to Schneider, the police had protested that the audience and performers, all cross-dressed men, were “nothing but fags and queers,” at which point Slater rebuked them. “They then handcuffed Don and carted him off to jail, with Don cussing them out at the top of his voice all the way for wasting the taxpayer’s money.”[12] Slater’s subsequent complaints lead to a change in the city codes that denuded the Police Commission of its powers of censorship [13].

In 1968, Slater led a picket of the Los Angeles Times for the editorial board’s refusal to publish an advertisement for the play Geese, which portrayed two young (and occasionally naked) male lovers vis-à-vis their parents. [14] The Times policy was changed—another significant victory for Slater, who later conducted after-the-show discussions with the audience.

In the 1970s, Slater wrote to politicians encouraging them to court the votes of homosexuals. With Hay, he also picketed the offices of Legg’s ONE, Incorporated, for having supported a homophobic city councilman. When others picketed Barney’s Beanery restaurant, however, in effort to have the owners remove a sign that said “Fagots Keep Out” [sic], Slater stayed home, saying that the owner had the right to serve whom he pleased. Morris Kight and Rev. Troy Perry had organized this successful demonstration, and Joseph Hansen was on site with a tape recorder, interviewing Perry for a later broadcast on his homosexual-themed radio show, broadcast on KPFK. Slater, it should be added, was less than impressed with Perry, whom he considered a gay separatist and therefore a “false prophet.”[15]. Ever the iconoclast, Slater often turned his wit and scanty resources against his fellow gays, as much the Diogenes of the movement as its gadfly.

It is difficult to capture the cantankerous spontaneity of Slater’s wit and daring. As Billy Glover told me, “What is hard to put on paper that showed Don’s truly remarkable character is how he constantly used the courts to make his points and try to force others to be honest.” Glover recalled an incident in which he had gone with Slater as a witness, in case of Slater’s arrest, to confront the Customs office for withholding a European publication, such as Revolt or Vennen. Slater asked the official if he could see the magazine. Once produced, Slater snatched it and said, “Oh yes, this is ours!” He proceeded to walk out of the office with two men shouting, “Mr. Slater, you can’t do that!” and a bemused Glover shuffling behind. Slater and Glover proceeded to the elevator with the prize, and they left.[16]

Sometimes Slater’s principles interfered with his manners, however, as when he refused to pay a neighbor in Colorado for work done on a water line that was to their mutual benefit, on grounds that he hadn’t been asked first. The neighbor took Slater and Sanchez to court over the issue, but the judge upheld Slater’s position. According to Glover, Slater would have paid if the neighbor had simply been more courteous.

A Pioneer Passes

In 1979, Slater had an artificial valve implanted in his heart. During the procedure he became infected with hepatitis B, and though the surgery was a success the virus almost killed him [17] Then, as he left HIC’s Hollywood office late one night in 1983, he was mugged and attacked in the dark parking lot behind the building. [18] Slater managed to return to the office, where he called Charles Lucas to ask for help. Lucas called fellow HIC board members Rudi Steinert and Susan Howe, who rushed to the office to find Slater drenched in blood.

The thugs had taken everything—his money and briefcase, but also his clothes, shoes, and car. Lucas wrapped Slater in a blanket and managed to get him down the fire escape and into his car. Rather than go to the hospital, Slater insisted that they take him home. Sanchez arrived home early the next morning, but by that time Slater had become so weak that he consented to be taken to the hospital.[19] According to Sanchez his wounds were superficial. [20] Lucas and Howe, though, recall that his face had been brutally smashed and bones had probably been fractured. No police report was filed on the incident. Sanchez’s car eventually showed up at the local compound, and Slater recovered very fast. Still, he had been lucky. He could easily have been killed in the incident, which Sanchez insists was not a hate crime but a mugging with the promise of sex used as lure or bait. At this time, Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue were notorious cruising grounds for hustlers, and it was not uncommon for one to stop into the HIC office and either request help or proffer assistance. It was one such rogue “volunteer” who had attacked Slater and taken his belongings—and nearly his life. The Hollywood offices of the HIC were subsequently closed, and the library and office were moved into Slater and Sanchez’s Victorian home on Calumet.

With the assistance of a Veteran’s Administration loan, Slater and Sanchez bought a second, more rustic house near the four corners area in Southwest Colorado, where Sanchez resides to this day. Through the 1980s, the two frequently travelled back and forth from Los Angeles to Colorado. Jennings and Glover occasionally made the twelve-hour drive as well. Slater loved the peace of the Colorado spread, but he also loved to be back home in Los Angeles, where he could tend to his shaded garden with the downtown spires standing like sentinels nearby. He and Sanchez added a rooster named Calhoun to their extended family of urban critters, including several dogs and cats.

In December of 1996, Slater suffered from a severe cardiac arrest.[21] He had neglected to have his aged heart valve replaced and now was too weak to undergo the procedure. He remained in the VA Hospital for the next two months, until he passed at ten at night on February 14, 1997, at seventy-three years old. His death took many by surprise. He had expected to live well into his eighties, as his father had before him.

At his death controversy immediately ensued as to what should happen to the rare and valuable materials Slater had collected over the years of working for ONE and HIC. After much deliberation, HIC’s surviving directors decided to archive them within the Vern and Bonnie Bullough Collection on Human Sexuality, a special collection held within Oviatt Library at California State University Northridge.

Notes

- ↑ Hansen 2002:103–104

- ↑ Hansen 1998; Hansen 2002

- ↑ 1998

- ↑ Hansen 2002:104

- ↑ Hansen 2002:?

- ↑ Hansen 2002:104

- ↑ a pseudonym

- ↑ Hansen 2002:106

- ↑ Personal Communication, Dec. 27, 2003

- ↑ Hansen 2002:106

- ↑ 1997

- ↑ Personal Communication

- ↑ Hansen 1998:71

- ↑ Kepner 1997

- ↑ Hansen 1998:70, 75

- ↑ Personal Communication, Feb. 14, 2004

- ↑ Hansen 2002:113.

- ↑ Lucas 1997

- ↑ ibid:86–87

- ↑ personal communication, Feb. 11, 2004

- ↑ Lucas 1997

References

- Hansen, Joseph. 1998. A Few Doors West of Hope: The Life and Times of Dauntless Don Slater. Universal City, CA: Homosexual Information Center.

- Hansen, Joseph. 2002. “Don Slater.’’ In Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context, edited by Vern L. Bullough, 103–114. Binghamton: Haworth Press.

- Kepner, James. 1997. “A Pioneer Passes.” In Don Slater: A Gay Rights Pioneer Remembered by his Friends. Los Angeles: Homosexual Information Center.

- Lucas, Charles. 1997. “The Happy Warrirors.” In Don Slater: A Gay Rights Pioneer Remembered by his Friends, 14–16. Los Angeles: Homosexual Information Center.

Text by C. Todd White. Copyright (©) by C. Todd White, 2008. All rights reserved.

Back to Exhibit Main Page

<comments />