Edward Field: 1924-present (Part III)

Poet Edward Field Writes His Own History (Part III)

continued from: Edward Field: 1924-present (Part II)

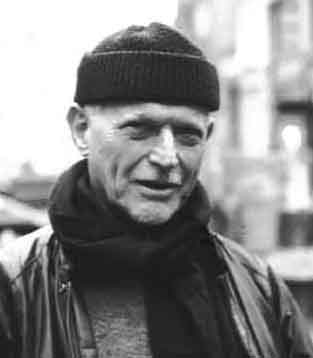

(Ed Field, 2002. Photo: Roger Netzer)

1971: Separation

Perhaps these explorations were a preparation for what happened one night in the late sixties, when my life was jolted in a new direction, unforeseen by horoscope or ouija board, and as crucial as my discovery of poetry on the troop train. Neil and I were living on Perry Street in Greenwich Village, and I awoke to find him having an epileptic seizure in bed beside me. I knew it was the end of something and the beginning of something else. We had been together for eight years. After much discussion, we both agreed that our close relationship might have been too constricting for him, and we separated in 1971.

Afghanistan

To try to recover my balance I went on a long, overland trip to Afghanistan, a country I had been drawn to since seeing photos in the National Geographic. My experiences in the heartland of Asia confirmed me in my new spiritual direction, and also helped me accept myself as a man. In Afghanistan, unlike the United States, men were allowed to be affectionate and there were no categories for the varieties of male sexuality. I started to see that my homosexuality was simply one of the possibilities for a man, and that, too, I had chosen. Well, maybe my sexuality had been distorted by my bringing up, but what I did with it was my own choice, and okay.

Westbeth

After living together for more than ten years, it was not easy for Neil and me to separate, especially with the tight housing situation in New York. When I returned from Central Asia, I applied for a studio in the Westbeth Artists' Housing Project in the West Village. I told the director I'd have to move out of the city if he couldn't give me a studio, and by some miracle, in spite of a long waiting list, he replied that that's what Westbeth was there for, to keep artists in the city, and assigned me a studio immediately. This turned out to be a long slice of a room with windows facing the Empire State Building. I could lie in my Yucatan hammock strung across the walls, looking at the changing light on the towers of Manhattan. May Swenson, when she sublet from me one winter, wrote a poem about it, called "Staying at Ed's Place."

Neil

Though Neil's seizures were being controlled by medication, he now started having visual blackouts and a brain tumor was diagnosed. The surgery took eight hours and he came out of it remarkably well, but over the following weeks lost most of his sight. Luckily, I was in Primal Therapy at the time, and would lie on the floor of the sound-proof studio and scream. I found myself crying not just for Neil, but for myself; not for my current grief, but for my whole life, and I discovered some significant things about my lifelong miseries.

Neil was in the hospital for three months, since the staff was afraid to let him go home where there was no family to look after him and I didn't qualify. But I managed to convince them to release him weekends in my care, and that's when I started learning to look after a blind man, as he was learning how to live like one. In spite of our having broken up two years before, there was no question in my mind of walking away from this situation, and the decision to stick with him has shaped the rest of my life. It’s a lot of work, but I’m a workhorse. Perhaps some people are born to be care-givers. My horoscope puts me in the "devotional" decan of Gemini. It might be a coincidence, but another person born the day before me is remarkably like me in this regard, Sylvia Winner, married to the late poet Robert Winner, a quadriplegic. For myself, I have to admit that having to deal with someone else’s troubles is a great escape from my own shit.

While Neil went off to a Veterans Administration blind training school, I headed south in my Volkswagen van for a term as poet-in-residence at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida. Though I had taught poetry workshops in colleges around New York City, Eckerd was my only real experience living on a college campus and confirmed for me that that was not the life I wanted to lead. One of the chief rewards of teaching was that a few students became lasting friends. But for me, poetry did not belong to academia. Before the poetry workshop and the MFA program became dominant, poets were self-taught. True, I had the luck to meet Robert Friend, but I doubt that any class could have given me what he gave me.

Neil had been to Europe many times, starting with a bicycle tour of England and France after high school, and a college year abroad. He had lived for those trips, but now with his blindness there seemed little point in him traveling any more. But a year after his operation, when friends Shami and Joseph Chaikin went with the Open Theater to London, we took a chance and followed them, renting a bedsit for a month. Neil quickly discovered that, even with practically no vision, foreign travel was still satisfying. And I found I could cope with the extra burdens of leading him around and handling all the arrangements, though I continue to have nightmares about missing trains and planes and, worst of all, losing him.

New Chapter

Thus began a new chapter in my life. Since Stand Up, Friend, With Me came out in 1963, I'd had exactly the kind of career I wanted. It was a small but very satisfying one, where I could do everything by myself, with a classy publisher, good reception all over the country on my reading tours, reviews, fan mail -- all the attention I needed. I even earned my living at it. But taking care of Neil after he went blind became more important. It was the first time in my life I had ever felt so useful and, not wanting to leave him alone for long and disliking the visiting-poet routine at colleges, I cut way down on poetry readings. When Grove Press was sold in the mid-seventies and I lost my publisher, it seemed that a cycle had finished. That feeling was intensified when my next book, A Full Heart, published in 1977 by Sheep Meadow Press, founded by my friend Stanley Moss, was badly mauled in the New York Times.

The Potency Clinic

Neil could manage much of the business of life on his own, and even went around the city bravely with his white cane. But he wasn't much good in the kitchen and there were a lot of other things a pair of eyes was useful for. When he was sighted, he had published half a dozen soft-porn novels, and though he could now write a first draft on the typewriter, he couldn't read back what he wrote, which led to my working with him on his fiction. I'd been invited for another stay at Yaddo, so, before leaving, I helped him plot a novel chapter by chapter, and during the two months I was away he wrote the first draft. When I got back, I helped him revise it, resulting in The Potency Clinic, a comic coming-out novel, by Bruce Elliot, one of Neil's pseudonyms from his soft-porn days. But though I sent it on the rounds of publishers, none was ready for its sassy humor, so in 1978 we published it ourselves in a small edition under the imprint of Bleecker Street Press. I found this experience as a publisher a lot of fun—finding a cheap printer, sending copies to literary critics, publications, and bookstores, filling orders, getting reviewed, and hearing from readers.

It was especially satisfying when a trio of young Germans who were setting up a gay publishing house, Albino Verlag, wrote that they wanted to buy the German-language rights for their first season's list, which included Jean Cocteau and James Purdy. They were attracted to the novel especially because it was humorous, a rare quality in gay novels at that time.

1979: A Geography of Poets

I'd always resisted writing anything but poetry, but I was loosening up. I had been all over the country, except to the deep south, on my reading tours, and now got the idea of editing an anthology of contemporary poetry that would present what poets were doing in each region. Ted Solotaroff, who was an editor at Bantam Books at the time, liked the idea and got me a contract for A Geography of Poets (1979). In order to get a different perspective on American poetry, Neil and I went to live in San Francisco for several months, to try to escape the usual New York-centered view of what was going on "out there" in the country and present a balanced selection of poets for once. But that turned out to be its flaw in the eyes of the Establishment. The book wasn't reviewed in the New York Times, because, as the editor of the book review section told me, it was an anti-New York anthology. Although it only remained in print for several years, I keep running into people, especially on the west coast, who studied it in their literature classes.

1982: Village

Wherever we were or whatever we were doing, Neil and I were always inventing plots for novels. We had so many ideas we talked of going into the plots business. So we were more than ready for another project to work on together, when, out of the blue, Bob Wyatt, an editor at Avon Books who specialized in original paperbacks, gave us the chance to write a big, popular, "generations" novel about Greenwich Village. Village (1982) by Bruce Elliot, Neil's pseudonym which now became ours, followed a New York family over the years from 1845 when they moved into a house on Perry Street in the Village until the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. We researched Village and New York History, and much of the story grew out of historical events. We had a lot of fun with the plot, some of it borrowed from our favorite movies, but much of it quite original, incorporating themes of race and religion that have been significant in American life.

Every bit of it was written together. Neil would be at the typewriter while I would sit next to him scrawling revisions on the manuscript. Perhaps it was due to our laborious method, but we worked far longer hours than I ever had on poetry. For me, writing prose is a more “literary” exercise than poetry and we settled on every sentence only after many, often fierce, struggles. But all was miraculously forgiven when a chapter was done. My feeling about collaborating is that you can only do it if nothing will break you up.

We finished a chunk of the novel during a winter in my brother-in-law Ack Van Rooyen's house in The Hague. It was the first of numerous stays in Holland and the beginning of our love affair with the Dutch. We lived in the attic room where the North Sea squalls beat on the tiled roof, but a little gas stove kept us warm. We would walk in the pale light of midday to the nearby beach resort of Scheveningen and eat herrings from a fish stall. I could only struggle with the Dutch language and its impossible gutterals, but somehow made myself understood in the shops.

We turned out Village in eighteen months, and for the first time I experienced the full treatment from a publisher, so different from having a book of poems published. After conferences, our editor even walked us to the elevator! No expense was spared to give the book popular appeal. An artist was commissioned to paint original scenes from the book for the end papers, and there were three different-colored covers for the bookstore racks. It made the B. Dalton best-seller list, and there was a window devoted to it at the store's Village branch, placards in the subways, full-page ads in women's magazines. It was astounding how much money we earned. With 220,000 copies sold, it was exhilarating to get those large royalty checks after the chickenfeed from poetry. Of course, I continued to write poetry as always. It's just that now I was writing prose as well. No matter what else I'm involved in, deep down I've never deserted my commitment to poetry.

The Prix de Rome

Due to the initiative of my old friend May Swenson, a fellow at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, I was awarded the Prix de Rome, and we left for the year in Rome feeling that from then on, with our success with the novel, we would be able to spend longer periods of time abroad. Our experience at the American Academy in Rome was not a happy one. Neil hated the dormitory living arrangements, with the bathroom down the hall and graduate student mateyness between the fellows. So we decided to leave and rent our own apartment, which caused a crisis in the head office. "This is an educational institution with rules," I was told by the director, and if I moved out, I would relinquish my fellowship.

The director ultimately backed down, and we escaped to our own apartment, though I continued to work in my studio in the Academy garden. But Rome, beautiful as it was, was impenetrable, and leaving it for good in May 1982 was a relief. We were heading for Berlin where in June Die Potenz Klinik by Bruce Elliot, translated into German by Gerhard Hoffmann, was coming out. We stopped off in Athens, where I still remembered some Greek from my stay in 1949, and then spent a few days in iron-curtain Sofia before flying on to Germany. One of the publishing team at Albino Verlag, Peter Schmittinger, who has since died of AIDS, showed us West Berlin in his car, and there was a book signing in Prinz Eisenherz, the gay bookstore, where I signed for Neil. And throughout the entire week, blackbirds sang outside the window of our room in a pension.

On our previous visit to Berlin, when we stayed with my sister and brother-in-law, I'd felt slightly repelled by the post-war prosperity—I still had my wartime view of the Germans—but now I succumbed to the glamour of history, the drama of being in Germany, where there is plenty to remind one that “it happened here.” I feel deeply united to this city that I bombed five times. Everywhere, the twelve years of Nazism remain vivid, and the eye even puts together the remanants of the heavy, ornate Wilhelminian city destroyed in the bombing. And overlaying that, the divided city of the cold war, the two sides so different, each with its own qualities. The austereness of East Berlin, when we went over, seemed a relief from the glitzy, hyped-up West. In fact, every visit to Germany from then on, has been a welcome change from the messiness of life in New York.

1987: The Office

After the success of Village, it looked like Neil and I were set up to live off writing novels together. Our editor even called us in for a discussion of another idea he had, a novel set in a Manhattan office. Unfortunately, though we threw in drug dealing, suicide, wife beating, a sexy rat of a boss who leads our heroine typist a merry chase for years, The Office (1987) by Bruce Elliott (another "t" was added to our pseudonym) did not sell. Suddenly, we were box office poison and that ended Bruce Elliot(t)'s career.

But even with our income now limited to our pensions and my pitiful earnings, we've held to our determination to live abroad as much as possible. I love speaking other languages. Whenever I'm in a place where a different language is spoken, I feel a wonderful sense of possibility. My French isn’t bad, especially in the Arab world where it’s a second language, but I also love to speak German, even badly, though I continue to study it daily. In addition, travel is good for my ego, especially in the Arab world—they don't even notice you're old. In France, too, a man of my age is treated with considerable respect. Though we've made numerous trips to Tunisia, Morocco, Turkey, Egypt, and various eastern European countries, as well as throughout Europe, it is most satisfying to rent an apartment and actually live there. after visiting Germany frequently over the years and several times renting apartments in West Berlin, most recently we stayed for a few months in what used to be East Berlin. We've lived most often in London, often in the remarkably-lively, cosmopolitan neighborhood of Queensway, and more recently in the remote, decidedly-working-class borough of Hackney.

The Alfred Chester Project

My generation had the romantic idea, no, the imperative, that you must destroy yourself for your art, as Hart Crane did, and Rimbaud. Like communism, being an artist meant working for posterity, not the present. Somehow I survived this illusion, though my friend, Alfred Chester, lived by it, and in 1971, died miserable and insane in Jerusalem. With all the attention he had received in his short life and publishing career, by the time of his death he was completely forgotten. Ten years later in the early eighties, I began my Alfred Chester Project, to get him back into print and revive his reputation. This led to our becoming friends with Alfred's English editor, Diana Athill, a remarkable writer herself, whom Neil and I visit whenever we are in London.

But editors kept telling me that they couldn't publish Alfred Chester because he was forgotten, which, I replied, was exactly why I wanted him to be republished! It took several years, but I finally connected with Kent Carroll of Carroll & Graf, who reissued Alfred Chester's last novel The Exquisite Corpse in 1986, with an introduction by Diana Athill. A few years later, Black Sparrow Press published two volumes, his selected stories and then the selected essays, which I edited. After which, the editor of Black Sparrow Press published two books of my poetry, Counting Myself Lucky, Poems 1963-1992, which won a Lambda Award, and A Frieze For A Temple Of Love.

To help the Alfred Chester revival, I persuaded old friends to write about him, and Cynthia Ozick published a memoir in The New Yorker about their friendship and rivalry at NYU. I published my own essays about him in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Review, and The Dictionary of Literary Biography, as well as sending out sporadic issues of The Alfred Chester Newsletter. Recently, I've deposited my archive of Chester books, correspondence, and other materials in the library of the University of Delaware, along with my own papers.

1992: A New Geography of Poets

One inescapable fact about putting together a poetry anthology is that you have to read a lot of poetry. So when Gerald Locklin suggested that we do a sequel to A Geography of Poets, I started catching up on what had been going on in the poetry world since that last poetry-reading binge. If A Geography of Poets was a view of America from San Francisco and New York, its sequel A New Geography of Poets (1992), co-edited with my Long Beach buddies Stetler and Locklin, was a view of America from Southern California and New York. It was meant to celebrate the fact that, while no one was looking, a new kind of American poetry has been springing up in every corner of the country, a kind of poetry that is completely indigenous, emerging from the populist spirit, as opposed to the intellectual elitism of the northeast.

2007: Intimate Literary Portraits of the Bohemian Life

After more than half a century, it seems strange that I continue to be very much involved with poetry. But I must confess that I send out my poems less. The process of writing has been considerably changed by a computer. With its help I‘ve also become a prose writer, and have had essays in The Nation, Raritan, Michigan Quarterly, Parnassus, and the Harvard Gay and Lesbian Review, among other publications. In 2007, my literary memoirs, The Man Who Would Marry Susan Sontag, and Other Intimate Literary Portraits of the Bohemian Life, were published. This began as a collection of my essays, but when the editor Raphael Kadushin of the University of Wisconsin Press, pointed out that no one would buy a book of essays, I rewrote them as a narrative of my literary development. Since then, with the encouragement of the remarkable poet and editor of University of Pittsburg Press, Ed Ochester, another collection of poems has been published, After The Fall, Poems Old and New (2007). And World Parade Books published my diary from my summer in Afghanistan in 1970, Kabuli Days, Travels In Old Afghanistan.

Are there more books in me? I hope so. Another book of poems, perhaps. Another memoir, one in which I spill the beans about my own intimate life.

2009: At eighty-five

At eighty-five, in 2009, I go on evolving. My generation of artsy people scorned anything like exercises, everything to do with the body, really, except sex. The body stood for the stupid people, conventional, brutal people. But years ago, Reichian study and Primal Therapy demonstrated to me that everything is locked up in the body, and since then I have looked on it as a map of my life. I am still working on unlocking its secrets, developing toward perfect openness. Every night before bed, in my hour for myself, I do my yoga exercises, and use them to explore what’s going on within me. If I have never regained the ultimate freedom I felt after I “stood up” in my group, I keep working toward it. At least, while I work out, my body is transformed from an old man’s to a lithe and balanced one. Going through the alphabet of movements, ending up in the lotus posture with which I finish my set, I feel the possibility of becoming whole again. And I write down the insights, the words that come to me, as I have always done. My poetry will always be a healing.

As I write this, my world is on the verge of extinction. Everything is different and I may be an anomaly, but I still feel that the Left, whatever its errors and ideological faults, generally has the best orientation for a livable society. The major theme in my poetry has been speaking up for the poor, the unwanted, the underdog, and by extension, the "lower" functions of the body. True to my Jewish traditions, I write from the heart, though that is unfashionable in our increasingly selfish, market-oriented universe.

When I started writing, I wanted my poetry to save the world. I saw myself standing up in the marketplace and speaking to the people. Later, I desperately believed, against the literary dogmas in fashion, that poetry could save me. In spite of the evident truth that poetry can change nothing, I trust the instincts of the young and why they are attracted to poetry, as if it actually could overcome injustice. It has to do with an idealism that gets lost as you get older, especially as you get involved in the poetry world with its factions and power struggles. It has to do with poetry as magic, the magic of words.

I still believe it's a kind of magic.

Bibliography

Publications

Poetry

- Stand Up, Friend, With Me (Grove Press, l963)

- Variety Photoplays (Grove Press, l967)

- Eskimo Songs and Stories (Delacorte, l973)

- A Full Heart (Sheep Meadow Press, l977)

- Stars In My Eyes (Sheep Meadow Press, l978)

- The Lost, Dancing (Watershed Tapes, l984)

- New And Selected Poems (Sheep Meadow Press, l987)

- Counting Myself Lucky, Selected Poems l963 l992 (Black Sparrow, l992)

- A Frieze for a Temple of Love (Black Sparrow, 1998)

- Magic Words (Harcourt Brace, 1998)

- After The Fall, Poems Old & New (U. of Pittsburgh Press, 2007)

Poetry Chapbook and Broadsides

- “Curse of the Catwoman” (The Acre, 9 Robandy Road, Andover, MA 01810, 2003)

- "The Journey” (www.jacksbrook.com, 2007) illustrated by Jan Jutte

- “The Tailspin” (Poor Souls Press, Milbrae, CA, 2009)

Fiction (with Neil Derrick)

- The Potency Clinic (Bleecker Steet Press, l978)

- Die PotenzKlinik tr. Gerhard Hoffmann (Albino Verlag, Berlin, l982)

- Village (Avon Books, l982), and as The Villagers (Painted Leaf Press, 2000)

- The Office (Ballantine Books, l987)

Non-Fiction

- The Man Who Would Marry Susan Sontag, and Other Intimate Literary Portraits of the Bohemian Era (U. of Wisconsin Press, 2006, paperback edition, 2007)

- Kabuli Days, Travels In Old Afghanistan (WorldParadeBooks.com, 2008)

Anthologies and Editorial

- A Geography of Poets (Bantam Books, l979)

- A New Geography of Poets (with C. Stetler/G. Locklin) (U. of Arkansas Press, l992)

- Ed., Head Of A Sad Angel, stories by Alfred Chester (Black Sparrow, l990). Intro by Gore Vidal

- Ed., Looking For Genet, essays by Alfred Chester (Black Sparrow Press, l992)

- Ed., Dancing With A Tiger, Selected Poems by Robert Friend (Spuyten Duyvil 2003)

Periodicals

Poetry and essays in The New Yorker, NY Review of Books, Gay & Lesbian Review, Partisan Review, Nation, Evergreen Review, NY Times Book Review, Michigan Quarterly, Raritan, Parnassus, Kenyon Review, etc.

Miscellaneous

- Wrote narration for documentary film, "To Be Alive" -- Academy Award, l965

- Readings at the Library of Congress, Poetry Center YMHA, and hundreds of universities

- Poet-in-residence, Eckerd College

- Taught poetry at Poetry Center YMHA, Sarah Lawrence, Hofstra U.

- Editor of The Alfred Chester Society Newsletter

Awards and Honors

- Lamont Award (Academy of American Poets), l962

- Guggenheim Fellowship, l963

- Shelley Memorial Award (Poetry Society of America), l974

- Prix de Rome (American Academy of Arts & Letters), l98l

- Lambda Literary Award, l993

- Bill Whitehead Lifetime Achievement Award (Publishing Triangle), 2005

- W.H. Auden Award (Sheep Meadow Foundation), 2005

Links

- WEBSITE: http://www.edwardfield.com

- VIDEOS: http://www.YouTube.com/fieldinski

- WORLD PARADE BOOKS: http://www.worldparadebooks.com

- BLACK SPARROW PRESS: http://www.blacksparrowbooks.com/author.asp?first=Edward&last=Field

- SHEEP MEADOW PRESS: http://www.upne.com/bip_index_0006.html

- UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PRESS Fall 2007 catalog:

- UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN PRESS: http://uwpress.wisc.edu/books/2099.h

- INTERVIEW ON NPR: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5449777

- GARRISON KEILLOR reading poem (November 27, 2007):

- INTERVIEW BY JERRY TALLMER: http://www.thevillager.com/villager_147/thelastbohemian.html

- ARCHIVE, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, U. OF DELAWARE LIBRARY: http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/findaids/field/field01.htm

- ACADEMY OF AMERICAN POETS: http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/696