Henry Gerber: "I wanted to help solve the problem," 1920-1925

From OutHistory

Jump to navigationJump to searchChicago Society for Human Rights; "To combat the public prejudices"

In 1953, twenty-nine years after the founding, in Chicago, of the Society of Human Rights, the earliest-known homosexual rights organization in the U.S., a short, anonymous letter from its founder, Henry Gerber, published in ONE, the then new homosexual emancipation monthly magzine, briefly described the fate of that early organization.[1]

In 1962, ONE magazine published a detailed account of the Chicago Society for Human Rights, written by Henry Gerber, this time under his own name.[2]

- Just 37 years ago, in 1925, a few of my friends and myself were dragged off to jail in Chicago causing our own efforts to ameliorate the plight of homosexuals to come to an early end.

- From 1920 to 1923, I had served with the Army of Occupation in Germany after World War I. En Coblenz on the Rhine I had subscribed to German homophile magazines and made several trips to Berlin…. I had always bitterly felt the injustice with which my own American society accused the homosexual of "immoral acts." I hated this society which allowed the majority, frequently corrupt itself, to persecute those who deviated from the established norms in sexual matters.

- What could be done about it, I thought. Unlike Germany, where the homosexual was partially organized and where sex legislation was uniform for the whole country, the United States was in a condition of chaos and misunderstanding concerning its sex laws, and no one was trying to unravel the tangle and bring relief to the abused….

- I realized at once that homosexuals themselves needed nearly as much attention as the laws pertaining to their acts. How could one go about such a difficult task [that of homosexual emancipation]? The prospect of going to jail did not bother me. 1 had a vague idea that I wanted to help solve the problem. I had not yet read the opinion of Clarence Darrow that "no other offence has ever been visited with such severe penalties as seeking to help the oppressed." All my friends to whom I spoke about my plans advised against my doing anything so rash and futile. I thought to myself that if I succeeded I might become known to history as deliverer of the downtrodden, even as Lincoln. But I am not sure my thoughts were entirely upon fame. If I: succeeded in freeing the homosexual, I too would benefit.

- What was needed was a Society, I concluded. My boss, whom I had pleased by translating a work of philosophy from the German, helped me write a Declaration of Purpose for our new Society for Human Rights, the same name used by the homosexuals of Germany for their work.[3] The first difficulty was in rounding up enough members and contributors so the work could go forward. The average homosexual, I found, was ignorant concerning himself. Others were fearful. Still others were frantic or depraved. Some were blasé.

- Many homosexuals told me that their search for forbidden fruit was the real spice of life. With this argument they rejected our aims. We wondered how we could accomplish anything with such resistance from our own people.

- The outline of our plan was as follows:

- 1. We would cause the homosexuals to join our Society and gradually; each as large a number as possible.

- 2. We would engage in a series of lectures pointing out the attitude of society in relation to their own behavior and especially urging against the seduction of adolescents.

- 3. Through a publication named Friendship and Freedom we would keep the homophile world in touch with the progress of our efforts. The publication was to refrain from advocating sexual acts and would serve merely as a, forum for discussion.

- 4. Through self-discipline, homophiles would win the confidence and assistance of legal authorities and legislators in understanding the problem; that these authorities should be educated on the futility and folly of long prison terms for those committing homosexual acts, etc.

- The beginning of all movements is necessarily small. I was able to gather together a half dozen of my friends and the Society for Human Rights became an actuality. Through a lawyer our program was submitted to the Secretary of State at Springfield, and we were furnished with a State Charter. No one seemed to have bothered to investigate our purpose.

- As secretary of the new organization I wrote to many prominent persons soliciting their support. Most of them failed to understand our purpose. The big, fatal, fearful obstacle seemed always to be the almost willful misunderstanding and ignorance on the part of the general public concerning the nature of homosexuality. What people generally thought about when I mentioned the word had nothing to do with reality…

- Nevertheless, we made a good start, even though at my own expense, and the first step was under way. The State Charter had only cost $10.00. I then set about putting out the first issue of Friendship and Freedom and worked hard on the second issue. It soon became apparent that my friends were illiterate and penniless. 1 had td both write and finance. Two issues, alas, were all we could publish. The most difficult task was to get men of good reputation to back up the Society. I needed noted medical authorities to endorse us. But they usually refused to endanger their reputations.

- The only support I got was from poor people: John, a preacher who earned his room and board by preaching brotherly love to small groups of Negroes; Al, an indigent laundry queen; and Ralph whose job with the railroad was in jeopardy when his nature became known. These were the national officers of the Society for Human Rights, Inc, I realized this start was dead wrong, but after all, movements always start small and only by organizing first and correcting mistakes later could we expect to go on at all. The Society was bound to become a success, we felt, considering the modest but honest plan of operation. It would probably take long years to develop into anything worth while. Yet I was will to slave and suffer and risk losing my job and savings and even my liberty for the ideal.

- One of our greatest handicaps was the knowledge that homosexuals don't organize. Being thoroughly cowed, they seldom get together. Most feel that as long as some homosexual sex acts are against the law, they should not let their names be on any homosexual organization's mailing list any more than notorious bandits would join a thieves' union. Today [1962] there are at least a half dozen homophile organizations working openly for the group, but still the number of dues-paying members is very small when we know that there are severa1 million homosexuals in the U.S.

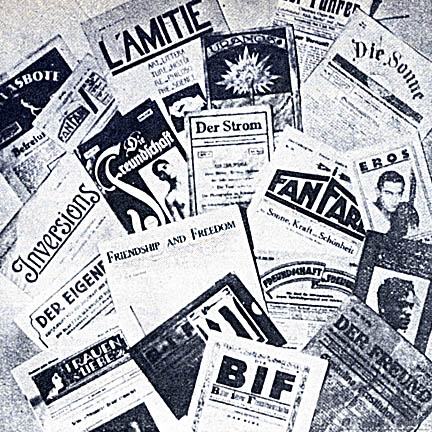

A copy of Friendship and Freedom, the "paper" published by the Chicago Society for Human Rights, appears prominently in 'this photo of a collection of early, mostly German, homosexual emancipation periodicals, verifying both the existence of the American periodical and suggesting the authenticity of Gerber's account. No copies of Friendship and Freedom are now known to be extant.[4]

A copy of Friendship and Freedom, the "paper" published by the Chicago Society for Human Rights, appears prominently in 'this photo of a collection of early, mostly German, homosexual emancipation periodicals, verifying both the existence of the American periodical and suggesting the authenticity of Gerber's account. No copies of Friendship and Freedom are now known to be extant.[4]

The Society, says Gerber "decided to concentrate our efforts on the State of Illinois," and to focus on reform of those laws criminalizing homosexual acts.

- We had agreed to make our organization a purely homophile Society, and we had argued and decided to exclude the much larger circle of bisexuals for the time being. Neither I nor John, our elected president, had been conscious of the fact that our vice-president, Al, was that type .In fact, we latex found out that he had a wife and two small children…

- One Sunday morning about 2 a.m., I returned from a visit downtown. After I had gone to my room, someone knocked at the door. Thinking it might be the landlady, I opened up. Two men entered the room. They identified themselves as a city detective and a newspaper reporter from the Examiner. The detective asked me where the boy was. What boy? He told me he had orders from his precinct captain to bring me to the police station. He took my typewriter; my notary public diploma, and all the literature of the Society and also personal diaries as well as my bookkeeping accounts. At no time did he show a warrant for my arrest. At the police station I was locked up in a cell but no charges were made against me. In the morning I was given permission to call my boss who, for my work's sake, fixed my status as "absent on leave."

- With a few other persons, unknown to me, I was taken to the Chicago Avenue Police Court where I also found John the preacher and Al the laundry queen and a young man who happened to be in Al's room at the time of arrest. No one knew what had happened. A friendly cop at the station showed me a copy of the Examiner. There right on the front page I found this incredible story:

Strange Sex Cult Exposed[5]

- The article mentioned Al who had brought his male friends home and had, in full view of his wife and children, practiced "strange sex acts" with them. Al's wife had at last called a social worker who reported these "strange doings" to the police. A raid of the flat, the report continued, had turned up John, a preacher, and Henry, a postal employee, and all were put under arrest. Among the effects in Al's flat they found a pamphlet of this "strange sex cult" which "urged men to leave their wives and children."

- What an outright untruth; what a perversion of facts! John was alone in his room when arrested, and I was too. We were not with Al; nor did we know of his being married and having children.

- There had been no warrants obtained for our arrests. The police, I suppose, had hoped or expected to find us in bed. They could not imagine homosexuals in any other way. My property was taken without excuse. This, in the United States anno domini 1925 with the Constitution to protect the people from unreasonable arrest and search. Shades of the Holy Inquisition.

- So, that was It! Al had confessed his sins but assured us that the reports of the detective and reporter were distorted. On Monday, the day after our arrest, in the Chicago Avenue Police Court, the detective triumphantly produced a powder puff which he claimed he found in my room. That was the sole evidence of my crime. It was admitted as evidence of my effeminacy. I have never in my life used rouge or powder. The young social worker, a hatchet-faced female, read from my diary, out of context: "I love Karl." The detective and the judge shuddered over such depravity. To the already prejudiced court we were obviously guilty. We were guilty just by being homosexual. This was the court's conception of our "strange cult."

- The judge spoke little to us and adjourned court with the remark he thought ours was a violation of the Federal law against sending obscene matter through the mails. Nothing in our first issue of Friendship and Freedom could be considered "obscene" of course.

- At this first trial the court dismissed us to the Cook County Jail. Our second trial was to be on Thursday. They separated John from Al and me. In our cell Al broke out crying and felt deeply crushed for having gotten us into the mess. George, who had been arrested with Al, did not lose any time while a guest of the Chicago police. Among the prisoners was a young Jew who asked me if I wanted a lawyer. He recommended a friend of his, a "shyster" lawyer who practiced around criminal courts. I made a request to see him and he appeared the next morning. He seemed to be a smart fellow who probably knew how to fix the State Attorney and judges. He had the reputation of making a good living taking doubtful cases. He also handled the bail bond racket and probably made additional money each month from this shady practice.

- The lawyer told me at once that our situation looked serious. But he said he could get me out on bail, He would charge $200.00 for each trial. I accepted his services, although I know that it would have been cheaper to merely accept the -mum fine of $200.00.

- We were in a tough spot…. The following Thursday the four of us were taken before the same judge. This time two post office inspectors were also present. Before the judge appeared in court, one of the inspectors promised that he would see to it that we got heavy prison sentences for infecting God's own country.

- As the trial began, our attorney demanded that we be set free since no stitch of evidence existed to hold us. The judge became angry and ordered our attorney to shut up or be cited for contempt. The post office inspectors said that the federal commissioner would take the case under advisement from the obscenity angle. The second trial was then adjourned until Monday. The lawyer made one last request that we be released on bail. The judge hemmed and hawed but set bail at $1,000.00 for each of us. The lawyer made all the arrangements and collected his fees.

- Being a free man once more, I went down to the post office to report for work. But I was told that I had been suspended-more of the dirty work of the post office inspectors. Next I called upon the managing editor of the Examiner. I confronted him with the article in the paper. He told me he would look into the matter and make corrections, but: nothing was ever done. I had no means to sue the paper, and that was the end of that.

- Meanwhile a friend of mine succeeded in getting me a better lawyer-the one who had made our request for a charter. He agreed to take my case, also for $200.00 a trial. Calling the shyster, I told him of my inability to pay for another trial …

- …I knew before hand that our case would be dismissed since my new lawyer advised me that everything had been "arranged" satisfactorily.

- The day of the third trial we met a new judge. The detective who had made the arrests was there, the prosecuting attorney, the two post office inspectors, and even my first lawyer who found he had become interested in the case. The judge, who had reviewed our earlier trials, immediately reprimanded the prosecution. He said "It is an outrage to arrest persons without a warrant. I order the case dismissed." Al who had pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct received a fine of $10.00 and costs. The social worker was not present at this trial. Our lawyer told the judge in the presence of the baffled post office inspectors that he knew for sure that the Commissioner would take no action as far as the alleged obscenity of mailed literature was concerned. The judge also ordered the detective to return my property to me. I got my typewriter, but my diaries had been turned over to the postal inspectors and I never saw them again. I had never put down in my diaries anything that could be used against me, fortunately…

- …The experience generally convinced me that we were up against a solid wall of ignorance, hypocrisy, meanness and corruption. The wall had won. The parting jibe of the detective had been, "What was the idea of the Society for Human Rights anyway? Was it to give you birds the legal right to rape every boy on the street?"…

- The lawyer advised me he could get my post office job back. But I had no more money for fees and took no action. After a few weeks a letter from Washington arrived advising me that I had been officially dismissed from the Post Office Department for "conduct unbecoming a postal worker." That definitely meant the end of the Society for Human Rights.[6]

References

- ↑ [Henry Gerber,] letter signed G.S., Washington, D.C., ONE (Los Angeles), vol.1. no. 7 (July 1953), p. 22.

- ↑ Henry Gerber, "The Society for Human Rights--1925," ONE Magazine (Los Angeles), vol. 10, no. 9 (Sept. 1962, pp. 5-10.

- ↑ The group to which Gerber refers was the Bund fur Menschcnrecht (The Society for Human Rights), founded in 1919 by Hans Kahnert. The Bund was the largest of the Gay groups in Germany during the 1920s, one that aimed at being a "mass" organization, and it criticized Wirschfeld's scientistic approach. The Bund seems to be the particular homosexual emancipation group with which Gerber identified. Three recently discovered articles, bylined "Henry Gerber, New York," appear in German homosexual emancipation journals edited by Friedrich Radzuweit, chairman of the Bund. Gerber's articles are: "Englische Heuchetei" [English Hypocrisy], Blatter fur Menschenreckt [Journal of Human Rights'] (Berlin), vol. 6, no. 15 (Oct. 1928), p.'4-5 (the subject is the prosecution in England of Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness) ; "Die Strafbestimmungen in den 48 Staaten Arnerikas und den amerikanischen Territorien fu gewisse Geschlechtsakte" ["The Penalties in the 48 American States and the American Territories for Certain Sexual Acts"], Blatter fur Menschanrecht, vol. 7, no. 8 (Aug. 1929), p. 5-11; "Zwei Dollars oder funfzehn Jahre Zuchthaus" ["Two Dollars or Fifteen Years in Prison]" Das Freundschaftsblutt ['The Friendship Journal"] (Berlin), vol. 8, no. 41 (Oct. 9, 1930), p. 4. I wish to thank James Steakley for providing the information in this and the following note.

- ↑ This photo, including Friendship and Freedom among a selection of Gay periodicals, originally appeared in Magnus Hirschfeld's article "Die Hommexualitat" in Leo Schidrowitz, ed., Sittengechichte des Lasters (Vienna: Verlag fur Kulturforshung , 1927), p. 301. It is reprinted in James D. Steakley's The Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany (N.Y.: Arno, 1975), opposite p. 78. I wish to thank James Steakley for providing a reproduction copy of this photo.

- ↑ An unsuccessful attempt was made to locate the newspaper story which Gerber says was headed "Strange Sex Cult Exposed and appeared in the Chicago Herald and Examiner, on the front page, probably on a Monday, probably in 1925. I am deeply grateful to Nick Patricca for voluntarily hiring a researcher who examined the front pages and skimmed the rest of (a microfilm of) this paper from Dec, 31, I924 to Dec 31, 1925. It is possible that the item appeared earlier in 1924, as the charter for the Society for Human Rights had been issued on Dec. 10 of that year.

- ↑ Henry Gerber, "The Society for Human Rights-1925," ONE Magazine (Los Angeles), vol. 10, no. 9 (Sept. 1962), p. 5-10.

Categories:

• Go to Next Article